Cleft lip and cleft palate: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 275: | Line 275: | ||

{{Commonscat|Cleft lip}} |

{{Commonscat|Cleft lip}} |

||

* [http://www.clapa.com Cleft Lip and Palate Association] |

* [http://www.clapa.com Cleft Lip and Palate Association] |

||

* [http://www.cleft.ie Cleft Lip and Palate Association of Ireland] |

|||

* [http://www.allianceforsmiles.org/ Alliance for Smiles Inc.] |

* [http://www.allianceforsmiles.org/ Alliance for Smiles Inc.] |

||

* http://www.plasticsurgery.org/public_education/procedures/CleftLipPalate.cfm |

* http://www.plasticsurgery.org/public_education/procedures/CleftLipPalate.cfm |

||

Revision as of 23:13, 13 May 2007

| Cleft lip and cleft palate | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Cleft lip and cleft palate, which can also occur together as cleft lip and palate are variations of a type of clefting congenital deformity caused by abnormal facial development during gestation. This type of deformity is sometimes referred to as a cleft. A cleft is a sub-division in the body's natural structure, regularly formed before birth. A cleft lip or palate can be treated with surgery soon after birth, vert successfully. Cleft lips or palates occur in somewhere between one in 600 and one in 800 births. The term hare lip is sometimes used colloquially to describe the condition because of the resemblance of a hare's lip. Interestingly, in Lun Heng (Chapter 6), the first century AD Wang Chong said, "If a pregnant woman eats rabbit, the baby will have a cleft lip." The Chinese word for cleft lip is tuchun, literally harelip.

A microform cleft is a very minor cleft where no surgery is required to correct it. A microform cleft can appear as small as a little dent in the red part of the lip or look like a scar.

Cleft lip

If only skin tissue is affected one speaks of cleft lip. Cleft lip is formed in the top of the lip as either a small gap or an indentation in the lip (partial or incomplete cleft) or continues into the nose (complete cleft). Lip cleft can occur as one sided (unilateral) or two sided (bilateral). It is due to the failure of fusion of the maxillary and medial nasal processes (formation of the primary palate).

-

Unilateral incomplete

-

Unilateral complete

-

Bilateral complete

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Cleft palate

Cleft palate is a condition in which the two plates of the skull that form the hard palate (roof of the mouth) are not completely joined. The soft palate is in these cases cleft as well. In most cases, cleft lip is also present. Cleft palate occurs in about one in 700 live births worldwide.[1]

Palate cleft can occur as complete (soft and hard palate, possibly including a gap in the jaw) or incomplete (a 'hole' in the roof of the mouth, usually as a cleft soft palate). When cleft palate occurs, the uvula is usually split. It occurs due to the failure of fusion of the lateral palatine processes, the nasal septum, and/or the median palatine processes (formation of the secondary palate).

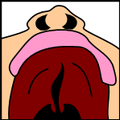

-

Incomplete cleft palate

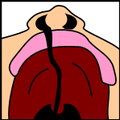

-

Unilateral complete lip and palate

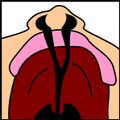

-

Bilateral complete lip and palate

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Prevalence among racial groups

It has been suggested that Clefting prevalence in different cultures be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2006. |

Prevalence rates reported for live births for Cleft lip with or without Cleft Palate (CL +/- P) and Cleft Palate alone (CPO) varies within different racial groups.

The highest prevalence rates for (CL +/- P) are reported for Native Americans and Asians. African-Americans have the lowest prevalence rates.[citation needed]

- Native Americans: 3.74/1000

- Japanese: 0.82/1000 to 3.36/1000

- Chinese: 1.45/1000 to 4.04/1000

- Caucasians: 1.43/1000 to 1.86/1000

- Latin Americans: 1.04/1000

- African-Americans: 0.18/1000 to 1.67/1000

Rate of occurrence of CPO is similar for Caucasians, African-Americans, North American Indians and Asians.

Prevalence of “cleft uvula” has varied from .02% to 18.8% with the highest numbers found among Chippewa and Navajo Indians and the lowest generally in African-Americans.[citation needed]

Causes of cleft

During the first six to eight weeks of pregnancy, the shape of the embryo's head is formed. Five primitive tissue lobes grow:

- a) one from the top of the head down towards the future upper lip;

- b-c) two from the cheeks, which meet the first lobe to form the upper lip;

- d-e) and just below, two additional lobes grow from each side, which form the chin and lower lip;

If these tissues fail to meet, a gap appears where the tissues should have joined (fused). This may happen in any single joining site, or simultaneously in several or all of them. The resulting birth defect reflects the locations and severity of individual fusion failures (e.g., from a small lip or palate fissure up to a completely deformed face).

The upper lip is formed earlier than the palate, from the first three lobes named a to c above. Formation of the palate is the last step in joining the five embryonic facial lobes, and involves the back portions of the lobes b and c. These back portions are called palatal shelves, which grow towards each other until they fuse in the middle.[2] This process is very vulnerable to multiple toxic substances, environmental pollutants, and nutritional imbalance. The biologic mechanisms of mutual recognition of the two shelves, and the way how they are glued together, are quite complex and obscure despite intensive scientific research. A comprehensive and easy to understand overview of palatal fusion with nice illustrations can be found in the March 2007 issue of Acta Histochemica.

The cause of cleft lip and cleft palate formation can be genetic in nature. A specific gene that increases three-fold the occurrence of these deformities has been identified in 2004 as reported by the BBC.[4]

Environmental influences may also cause, or interact with genetics to produce, orofacial clefting. Scientists have investigated seasonal causes (such as pesticide exposure); maternal diet and vitamin intake; retinoids, which are members of the vitamin A family; anticonvulsant drugs; alcohol; cigarette use; nitrate compounds; organic solvents; parental exposure to lead; and illegal drugs (cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, etc.) as teratogens that increase the possibility of clefting.

If a person is born with a cleft, the chances of that person having a child with a cleft, given no other obvious factor, rises to 1 in 14. Research continues to investigate the extent to which Folic acid can reduce the incidence of clefting.

In some cases, cleft palate is caused by syndromes which also cause other problems. Stickler's Syndrome can cause cleft lip and palate, joint pain, and myopia. Loeys-Dietz syndrome can cause cleft palate or bifid uvula, hypertelorism, and aortic aneurysm. Many clefts run in families, even though there does not seem to be any identifiable syndrome present.

Treatment

Within the first 2-3 months after birth, surgery is performed to close the cleft lip. While surgery to repair a cleft lip can be performed soon after birth, the oft preferred age is at approximately 10 weeks of age, following the "rule of 10s" coined by surgeons Wilhelmmesen and Musgrave in 1969 (the child is at least 10 weeks of age; weighs at least 10 pounds, and has at least 10 g haemoglobin). If the cleft is bilateral and extensive, two surgeries may be required to close the cleft, one side first, and the second side a few weeks later.

Often an incomplete cleft lip requires the same surgery as complete cleft. This is done for two reasons. Firstly the group of muscles required to purse the lips run through the upper lip. In order to restore the complete group a full incision must be made. Secondly, to create a less obvious scar the surgeon tries to line up the scar with the natural lines in the upper lip (such as the edges of the philtrum) and tuck away stitches as far up the nose as possible. Incomplete cleft gives the surgeon more tissue to work with, creating a more supple and natural-looking upper lip.

Often a cleft palate is temporary closed using a palatal obturator. The obturator is a prosthetic device made to fit the roof of the mouth covering the gap. Furthermore a tympanostomy tube is often inserted into the eardrum to aerate the middle ear. This is often beneficial for the hearing ability of the child.

Cleft palate can also be corrected by surgery, usually performed between 9 and 18 months. Approximately 20-25% only require one palatal surgery to achieve a competent velopharyngeal valve capable of producing normal, non-hypernasal speech. However, combinations of surgical methods and repeated surgeries are often necessary as the child grows. One of the new innovations of cleft lip and cleft palate repair is the Latham appliance. The Latham is surgically inserted by use of pins during the child's 4th or 5th month. After it is in place, the doctor, or parents, turn a screw daily to bring the cleft together to assist with future lip and/or palate repair.

If the cleft extends into the maxillary alveolar ridge, the gap is usually corrected by filling the gap with bone tissue. The bone tissue can be acquired from the patient's own chin, rib or hip.

Speech problems are usually treated by a speech-language pathologist. In some cases pharyngeal flap surgery is performed to regulate the airflow during speech and reduce nasal sounds.

Most children with a form of clefting are monitored by a cleft palate or craniofacial team through young adulthood. Care can be lifelong.

Note that treatment procedures can vary between craniofacial teams. For example, some teams wait on jaw correction until the child is aged 10 to 12 (argument: growth is less influential as deciduous teeth are replaced by permanent teeth, thus saving the child from repeated corrective surgeries), while other teams correct the jaw earlier (argument: less speech therapy is needed than at a later age when speech therapy becomes harder). Within teams treatment can differ from each individual case depending on the type and severity of the cleft.

Feeding Tip An infant with a cleft palate will have greater success feeding in a more upright position. Gravity will help prevent milk from coming through the baby's nose if he/she has cleft palate

Craniofacial team

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Craniofacial team. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2006. |

Cleft lip+/- palate is a congenital disorder of the craniofacial complex that occurs early during pregnancy and is present at birth. A cleft palate occurs when the shelves of the palate fail to meet or fuse, resulting in an opening in the roof of the mouth. A cleft lip occurs when the two sides of the lip are separated including the gum and or the upper jaw (http://www.cleftline.org/aboutclp/). Cleft lip+/- palate may affect early feeding, speech , dentition, hearing, velopharyngeal function and psychosocial development. Due to the multifaceted nature of this disorder, a timely coordinated approach by an interdisciplinary cleft palate or craniofacial team is essential to the management and care of this population. According to the American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association (ACPA), a cleft palate team provides assessment and treatment for cleft lip +/- palate only, while a craniofacial team provides assessment and treatment for craniofacial anomalies and associated syndromes (Strauss et al., 1998). The minimal requirement for a cleft palate team is a surgeon (see below), an orthodontist, and a speech-language pathologist (Strauss et al., 1998). Involvement of other professionals such as audiologists, psychologists (or other mental health professionals), otolaryngologists, pediatric and general dentists, audiologists, pediatricians, geneticists, social workers, pediatric nurse practitioners; radiologists, and otolaryngologists is not uncommon. Most children with a cleft palate evidence early, and usually treatable middle ear disease (otitis media).

The Surgeon, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon or a plastic and reconstructive surgeon, is critical member of the cleft palate team. Their role is to create a functional lip and palate that appears as normal as possible and provides support for the lip and base of the nose. This may, in some cases, require more than one surgery, including initial closure of the lip, initial closure of the palate, lip and nose revision, alveolar bone grafting, and if necessary, closure of oronasal fistula, and/or further palatal or pharyngeal surgery to eliminate hypernasal speech (Peterson-Falzone, Hardin-Jones, Karnell, 2001). Orthognathic surgery to align the upper and lower jaws may also be performed when the child is in his or her teens. The timing of these surgeries range from birth to the teenage years, and is based upon discussions with the orthodontist and surgeon.

The Orthodontist, whose specialty is the growth and development of the craniofacial complex, is one of the first cleft palate team members the family may encounter. The orthodontist’s evaluation of the newborn will help determine the timing of required surgeries as the child develops.

The Speech-Language Pathologist is also an essential member of the cleft palate team. Children with cleft palate, while having no trouble with normal language development, can often have delayed speech development due to their mouth's unusual anatomy. The speech-language pathologist will be involved in parent education, newborn feeding instruction, and evaluation and treatment of speech, language, voice and resonance disorders.

The evaluation and treatment of a child with cleft lip +/- palate requires ongoing services from a team of various professionals in a coordinated timely manner. Successful rehabilitation of the child is dependent on continued care by these professionals. Note that not all children with orofacial anomalies will require the care of a cleft palate team. For example, some children with submucous, or occult clefts of the palate, who do not have an impairment of speech/hearing may not need this service.

Velopharyngeal insufficiency

Velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) is defined as the failure to close the velopharyngeal sphincter, resulting in an inability to adequately separate the nasal cavity from the oral cavity(Armour et al., 2005) When there is a pharyngeal gap in the velopharyngeal sphincter during speech, air leaks into the nasal cavity resulting in a hypernasal voice resonance and nasal emissions (Sloan, 2000) Secondary effects of VPI include speech articulation errors (e.g., distortions, substitutions, and omissions) and compensatory misarticulations (e.g., glottal stops and posterior nasal fricatives) (Hill, 2001). VPI is most commonly caused by a cleft of the secondary palate, but other causes may include: submucous clefts, neuromuscular abnormalities, and congenital VPI of unknown cause (Sloan, 2000). Additionally, approximately 20-30% of patients develop VPI post primary palatoplasty (Heliovaara et al., 2003). Possible treatment options include speech therapy, prosthetics, augmentation of the posterior pharyngeal wall, lengthening of the palate, and surgical procedures (Sloan, 2000).

Complications

Cleft may cause problems with feeding (see also Haberman Feeder), ear disease, and speech. Due to lack of suction, an infant with a cleft may have troubles feeding. Individuals with cleft also face many middle ear infections which can eventually lead to total hearing loss. Because the lips and palate are both used in pronunciation, individuals with cleft usually need the aid of a speech therapist.

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Psychosocial issues

A cleft palate may impact an individual’s self-esteem, social skills, and behavior. There is a large amount of research dedicated to the psychosocial development of individuals with cleft palate. Self-concept may be adversely affected by the presence of a cleft palate. Research has shown that during the early preschool years (ages 3-5), children with cleft palate tend to have a self-concept that is similar to their peers without a cleft. However, as they grow older and their social interactions with other children increase, children with clefts tend to report more dissatisfaction with peer relationships and higher levels of social anxiety. Experts conclude that this is probably due to the associated stigma of visible deformities and speech abnormalities, if present. Children who are judged as attractive tend to be perceived as more intelligent, exhibit more positive social behaviors, and are treated more positively than children with cleft palate (Tobiasen, 1984). Children with clefts tend to report feelings of anger, sadness, fear, and alienation from their peers. Yet these children were similar to their peers in regard to “how well they liked themselves.”

The relationship between parental attitudes and a child’s self-concept is crucial during the preschool years. It has been reported that elevated stress levels in mothers correlated with reduced social skills in their children (Pope & Ward, 1997). Strong parent support networks may help to prevent the development of negative self-concept in children with cleft palate. In the later preschool and early elementary years, the development of social skills is no longer only impacted by parental attitudes but is beginning to be shaped by their peers. A cleft palate may affect the behavior of preschoolers. Experts suggest that parents discuss with their children ways to handle negative social situations related to their cleft palate. A child who is entering school should learn the proper (and age-appropriate) terms related to the cleft. The ability to confidently explain the condition to others may limit feelings of awkwardness and embarrassment and reduce negative social experiences [5].

As children reach adolescence, the period of time between age 13 and 19, the dynamics of the parent-child relationship change as peer groups are now the focus of attention. An adolescent with cleft palate will deal with the typical challenges faced by most of their peers including issues related to self esteem, dating, and social acceptance (Snyder, Bilboul, & Pope, 2005; Endriga & Kapp-Simon, 1999; Pope & Snyder, 2004). Adolescents, however, view appearance as the most important characteristic above intelligence and humor (Prokhorov et al., 1993). This being the case, adolescents are susceptible to additional problems because they cannot hide their facial differences from their peers. Males typically deal with issues relating to withdrawal, attention, thought, and internalizing problems and may possibly develop anxiousness-depression and aggressive behaviors (Pope & Snyder, 2004). Females are more likely to develop problems relating to self concept and appearance. Individuals with cleft palate often deal with threats to their Quality of Life for multiple reasons including: unsuccessful social relationships, deviance in social appearance, and multiple surgeries. Individuals with cleft palate often have lower QOL scores than their peers. Psychosocial functioning of individuals with cleft palate often improves after surgery, but does not last due to unrealistic expectations of surgery.

Having a cleft palate does not inevitably lead to a psychosocial problem. However, it is important to remember that adolescents with cleft palate are at an elevated risk for developing psychosocial problems especially those relating to self concept, peer relationships, and appearance. It is important for parents to be aware of the psychosocial challenges their adolescents may face and to know where to turn if problems arise.

The links below are a source of information regarding parent support networks and social development of children with cleft palate.

Controversy

In some countries cleft lip or palate deformities are considered reasons (either generally tolerated or officially sanctioned) to perform abortion beyond the legal fetal age limit, even though the fetus is not in jeopardy of life or limb. Some human rights activists contend this practice of "cosmetic murder" amounts to eugenics. A London clergywoman, who suffered from a congenital jaw deformity herself (not a cleft lip or palate as is sometimes reported), has started legal action to stop the practice in the UK as reported by CNN[6] and the BBC [7].

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Famous people born with a cleft

Historical

| Name | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tutankhamun | Egyptian Pharaoh who may have had a cleft lip according to diagnostic imaging | [3] |

| Doc Holliday | Dentist, gambler and gunfighter of the American Old West frontier | |

| Tad Lincoln | Fourth and youngest son of President Abraham Lincoln | [4] |

| Thomas Malthus | 18th and 19th Century English demographer and political economist |

Modern

| Name | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tom Brokaw | American television journalist with NBC News | |

| Carmit Bachar | American dancer and singer | |

| Jürgen Habermas | German philosopher and sociologist | |

| Wendy Harmer | Australian comedian | |

| Michael Helm | Canadian novelist | |

| Jesse Jackson | American politician, professional civil rights activist and Baptist minister | |

| Stacy Keach | American actor and narrator | [5] |

| Annie Lennox | Scottish pop musician and vocalist | |

| Tim Lott | English novelist | |

| Rita MacNeil | Canadian country and folk singer | |

| Peyton Manning | American NFL quarterback | |

| Cheech Marin | American comedian and actor | |

| Geoff Plant | Canadian lawyer and politician, Attorney-General of British Columbia | |

| Jason Robards | Academy, Emmy, and Tony Award winning actor | |

| Nikki Payne | Canadian comedian and actress | |

| Eric Edgar Cooke | Criminal, the last person to be hanged in Western Australia | |

| Mark Hamill | American actor and voice actor for video games | |

| Richard Hawley | English guitarist, singer, songwriter and producer |

The popular belief that Joaquin Phoenix has a cleft lip is mistaken. The mark on his lip is a microform, an almost-cleft that healed itself in utero. If the tissues joined up just enough to create correct bone and muscle tissues, no corrective surgery is required, as is the case with Phoenix.

Cleft lip and palate in animals

Cleft lips and palates are occasionally seen in cattle and dogs, and rarely in sheep, cats, horses, and ferrets. Most commonly, the defect involves the lip, rhinarium, and premaxilla. Clefts of the hard and soft palate are sometimes seen with a cleft lip. The cause is usually hereditary. Brachycephalic dogs such as Boxers and Boston Terriers are most commonly affected.[6] An inherited disorder with incomplete penetrance has also been suggested in Shih tzus, Swiss Sheepdogs, Bulldogs, and Pointers.[7] In horses, it is a rare condition usually involving the caudal soft palate.[8] In Charolais cattle, clefts are seen in combination with arthrogryposis, which is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait. It is also inherited as an autosomal recessive trait in Texel sheep. Other contributing factors may include maternal nutritional deficiencies, exposure in utero to viral infections, trauma, drugs, or chemicals, or ingestion of toxins by the mother, such as certain lupines by cattle during the second or third month of gestation.[9] The use of corticosteroids during pregnancy in dogs and the ingestion of Veratrum californicum by pregnant sheep have also been associated with cleft formation.[10]

Difficulty with nursing is the most common problem associated with clefts, but aspiration pneumonia, regurgitation, and malnutrition are often seen with cleft palate and is a common cause of death. Providing nutrition through a feeding tube is often necessary, but corrective surgery in dogs can be done by the age of twelve weeks.[6] For cleft palate, there is a high rate of surgical failure resulting in repeated surgeries.[11] Surgical techniques for cleft palate in dogs include prosthesis, mucosal flaps, and microvascular free flaps.[12] Affected animals should not be bred due to the hereditary nature of this condition.

-

Cleft lip in a Boxer

-

Cleft lip in a Boxer with premaxillary involvement

-

Same dog as picture on left, one year later

This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

See also

Treatment/aids

Syndromes

Organizations

- Alliance for Smiles

- Operation Smile

- Transforming Faces Worldwide

- The Smile Train

- Shriners Hospitals for Children

External links

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association

- Cleft Lip and Palate Association of Ireland

- Alliance for Smiles Inc.

- http://www.plasticsurgery.org/public_education/procedures/CleftLipPalate.cfm

- http://www.cleftline.org/parents/feeding_your_infant

- American Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Association

- Bangalore classification

References

- ^ "Statistics by country for cleft palate". WrongDiagnosis.com. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Dudas et al. (2007): Palatal fusion – Where do the midline cells go? A review on cleft palate, a major human birth defect. Acta Histochemica, Volume 109, Issue 1, 1 March 2007, Pages 1-14

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ a b Ettinger, Stephen J.;Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed. ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Garcia, J.F. Rodriguez (2006). "Surgery of the Soft and Hard Palate". Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ Semevolos, Stacy A. (1998). "Surgical Repair of Congenital Cleft Palate in Horses: Eight Cases (1979–1997)" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mouth". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ Beasley, V. (1999). "Teratogenic Agents". Veterinary Toxicology. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

- ^ Lee J, Kim Y, Kim M, Lee J, Choi J, Yeom D, Park J, Hong S (2006). "Application of a temporary palatal prosthesis in a puppy suffering from cleft palate". J. Vet. Sci. 7 (1): 93–5. PMID 16434860.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Griffiths L, Sullivan M (2001). "Bilateral overlapping mucosal single-pedicle flaps for correction of soft palate defects". Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 37 (2): 183–6. PMID 11300527.

- Hill, J.S. (2001). Velopharyngeal insufficiency: An update on diagnostic and surgical techniques. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, 9, 365-368.

- Liedman-Boshki, J., Lohmander, A., Persson, C., Lith, A., & Elander, A. (2005). Perceptual analysis of speech and the activity in the lateral pharyngeal walls before and after velopharyngeal flap surgery. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery, 39, 22-32.

- Mazaheri, M., Athansiou, A.E., & Long, R.E. (1994). Comparison of velopharyngeal growth patterns between cleft lip and/or palate patients requiring or not requiring pharyngeal flap surgery. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 31, 452-460.

- Meek, M.F., Coert, J.H., Hofer, S.O., Goorhuis-Brouwer, S.M., & Nicolai, J.A. (2003). Short term and long-term results of speech improvement after surgery for velopharyngeal insufficiency with pharyngeal flaps in patients younger and older than six years old: Ten year experiment. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 50(1), 13-17.

- Pena, M., Choi, S., Boyajian, M., Zalzal, G. (2000). Perioperative airway complications following pharyngeal flap palatoplasty. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, Laryngology, 109, 808-811.

- Peterson-Falzone, S.J., Hardin-Jones, M.A., & Karnell, M.P. (2001). Cleft Palate Speech (3rd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

- Sloan, G.M. (2000). Posterior pharyngeal flap and sphincter pharyngoplasty: The state of the art. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 37(Sloan, 2000), 112-122.

- Tonz, M., Schmid, I., Graf, M., Mischler-Heeb, R., Weissen, J., & Kaiser, G. (2002). Blinded speech evaluation following pharyngeal flap surgery by speech pathologists and lay people in children with cleft palate. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 54(6), 288-295.

- Witt, P.D., Myckatyn, T., & Marsh, J.L.(1998). Salvaging the failed pharyngoplasty: Intervention outcome. Cleft Palate—Craniofacial Journal, 35(5), 447-453.

- Ysunza, A., Pamplona, C., Ramirez, E., Molina, F., Mendoza, M., & Silva, A. (2002). Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 110(6), 1401-1407.

- Ysunza, A., Garcia-Velasco, M., Garcia-Garcia, M., Haro, R., Valencia, M. (1993). Obsrtuctive sleep apnea secondary to surgery for velopharyngeal insufficiency. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 30(4), 387-390.

- Croen, L.A., Shaw, G.M., Wasserman, C.R., & Tolarova, M.M. (1998). Racial and ethnic variations in the prevalence of orofacial clefts in California, 1983-1992. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 79, 42-47.

- Peterson-Falzone, SJ, Hardin-Jones, MA and Karnell, MP. (2001) Cleft Palate Speech. (3rd edition). St. Louis: Mosby, Inc.

- Kuehn, D. P., & Moller, K. T. (2000).Speech and Language Issues in the Cleft PalatePopulation: The State of the Art. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal ,37, 348-348.

- Marino, V.C.C., Williams, W.N., Wharton, P.W., Paulk, M.F., Dutka-Souza, J.C.R.,& Schulz, G.M. (2005). Immediate and Sustained Changes in Tongue Movement With an Experimental *Palatal “Fistula”: A Case Study. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 42, 286–296.

- "Maxillofacial Prosthetics." Rhode Island Department of Human Services. Rhode IslandDepartment of Human Services. 10 July 2006<http://www.dhs.ri.gov/dhs/heacre/ provsvcs/manuals/dental/maxpros.htm>.

- Peterson-Falzone, S., Hardin-Jones, M., & Karnell, M. (2001). Cleft Palate Speech(3rd ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

- Pinborough-Zimmerman, J., Canady C., Yamashiro, D.K., & Morales Jr., L. (1998). Articulation and Nasality Changes Resulting from Sustained Palatal Fistula Obturation. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 35, 81–87.

- Resiberg, D. J (2000). Dental and Prosthodontic Care for Patients With Cleft orCraniofacial Conditions. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 37, 534–537.

- Achenbach. T.M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Press.

- Endriga, M. C. & Kapp-Simon, K.A. (1999). Psychological issues in craniofacial care: State of the art. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 36, 1.

- Endriga, M.C., Jordan, J. & Speltz, M.L. (2003). Emotion self-regulation in preschool-aged children with and without orofacial clefts. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 24(5). 336-344.

- Harper, D.C. (1995). Children's attitudes to physical differences among youth from western and non-western cultures. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal. 32.

- Kapp, K.A. (1979). Self concept of the cleft lip and/or palate children. Cleft Palate Journal. 16, 171-176.

- Kruckenberg, S.M. & Kapp-Simon, K.A. (1993). Effect of parental factors on social skills of preschool children with craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 30, 490-496.

- Kruckenberg, S.M., Kapp-Simon, K.A. & Ribordy, S.C. (1993). Social skills of preschoolers with and without craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 30, 475-481.

- La Greca, A.M. (1990). Social consequences of pediatric conditions: fertile area for future investigation and intervention. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 15.

- Leonard, B.J., Brust, J.D., Abrahams, G., & Sielaff, B. (1991). Self-concept of children and adolescents with cleft lip and/or palate. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 28, 347-353.

- Pope, A.W. & Snyder, H.T. (2004). Psychosocial adjustment in children and adolescents with a craniofacial anomaly: Age and sex patterns. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 42, 4.

- Pope, A.W. & Speltz, M.L. (1997). Research on Pyschosocial Issues of Children with Craniofacial Anomalies: Progress and Challenges. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 34, 371-372.

- Pope A.W. & Ward J. (1997). Self-perceived facial appearance and psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with craniofacial anomalies. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 34, 396-401.

- Prokohorov, A.V., Perry, C.L., Kelder, S.H., & Klepp, K.I. (1993). Lifestyle values of adolescents: Results from the Minnesota Heart Health Youth Program. Adolescence, 28.

- Richman, L.C. (1997). Facial and speech relationships to behavior of children with clefts across three age levels. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 34, 390-395.

- Richman, L.C. & Millard, T.L. (1997). Cleft lip and palate: longitudinal behavior and relationships of cleft conditions to behavior and achievement. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 22, 487-494.

- Sarwer, D.B. & Crerand, C.E. (2002). Psychological issues in patient outcomes. Facial Plastic Surgery, 18, 2.

- Snyder, H.T., Bilboul, M.J., & Pope, A.W. (2005). Psychosocial adjustment in adolescents with craniofacial anomalies: A comparison of parent and self-reports. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 42, 5.

- Tobiasen, J.M. (1984) Psychosocial correlated of congenital facial clefts: a conceptualization and model. Cleft Palate Journal, 21, 131-139.

- Topolski, T.D., Edwards, T.C., & Patrick, D.L. (2005). Quality of life: How do adolescents with facial differences compare with other adolescents? The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 42, 1.

- Myracel Saguid, S.J, Hardin-Jones, M.A, Karnell, M.P. Cleft Palate Speech, 3rd Edition.(2001) St. Louis: Mosby Inc.

- Strauss et al. (1998). Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Teams in the United States and Canada: National Survey of Team Organization and Standards of Care. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 35, 473-480.