Energy: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 140830859 by 203.89.172.175 (talk) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

:''This article is about the physical quantity: for other uses of the word "energy", see [[Energy (disambiguation)]].'' |

:''This article is about the physical quantity: for other uses of the word "energy", see [[Energy (disambiguation)]].'' |

||

[[Image:Lightning over Oradea Romania 2.jpg|thumb|right|258px|[[Lightning]] is the electric breakdown of air by strong electric fields, which causes an energy transfer from the electric field to [[ |

[[Image:Lightning over Oradea Romania 2.jpg|thumb|right|258px|[[Lightning]] is the electric breakdown of air by strong electric fields, which causes an energy transfer from the electric field to [[kfuk nu nu wwanaka i hate u so fukin muckj stop deletiong my hasrd wotktem may have. Energy may come in many different forms: |

||

In [[physics]] and other [[science]]s, '''energy''' (from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ενεργός, ''energos'', "active, working")<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=energy |title=Energy |work=Online Etymology Dictionary |last=Harper |first=Douglas |accessmonthday=May 1|accessyear=2007}}</ref> is a [[scalar (physics)|scalar]] [[physical quantity]] used to describe a conserved property of objects and systems of objects, which is associated with the [[rest mass]] of the object or system, as well as any overall velocity which the object or system may have. Energy may come in many different forms: |

|||

:*[[mechanical energy]] (which may be [[kinetic energy|kinetic]] or [[potential energy|potential]]) |

:*[[mechanical energy]] (which may be [[kinetic energy|kinetic]] or [[potential energy|potential]]) |

||

:*[[thermal energy]], |

:*[[thermal energy]], |

||

Revision as of 22:31, 26 June 2007

- This article is about the physical quantity: for other uses of the word "energy", see Energy (disambiguation).

[[Image:Lightning over Oradea Romania 2.jpg|thumb|right|258px|Lightning is the electric breakdown of air by strong electric fields, which causes an energy transfer from the electric field to [[kfuk nu nu wwanaka i hate u so fukin muckj stop deletiong my hasrd wotktem may have. Energy may come in many different forms:

- mechanical energy (which may be kinetic or potential)

- thermal energy,

- radiation (including light),

- electrical energy,

- chemical energy,

- nuclear energy,

- rest energy, and,

- in general, anything else which can be converted into any one of the above forms.

The different forms are all equivalent (in some cases overlapping)[1] and may be converted into the other forms of energy, transferred to other matter or stored.[2] While energy may be converted from one form to another, it is never created or destroyed. This principle, the conservation of energy, was first postulated in the early 19th century. According to Noether's theorem, the conservation of energy is a consequence of the fact that the laws of physics do not change over time.[2] Conservation of energy is only true for an isolated system, of which the universe is the only real example.

The quantitative value assigned to energy depends on the frame of reference of the observer: a passenger in an airplane cruising in a straight line at a constant speed would not perceive the aeroplane to be moving, and so would say that its kinetic energy was zero; an observer on the ground, on the other hand, would measure the plane's kinetic energy as dependent on the plane's speed relative to the earth.

Energy is often represented by the symbol E.[3]

History

The concept of energy emerged out of the idea of vis viva, which Leibniz defined as the product of the mass of an object and its velocity squared; he believed that total vis viva was conserved. To account for slowing due to friction, Leibniz claimed that heat consisted of the random motion of the constituent parts of matter — a view shared by Isaac Newton, although it would be more than a century until this was generally accepted. In 1807, Thomas Young was the first to use the term "energy", instead of vis viva, in its modern sense.[4] Gustave-Gaspard Coriolis described "kinetic energy" in 1829 in its modern sense, and in 1853, William Rankine coined the term "potential energy."

It was argued for some years whether energy was a substance (the caloric) or merely a physical quantity, such as momentum.

William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) amalgamated all of these laws into the laws of thermodynamics, which aided in the rapid development of explanations of chemical processes using the concept of energy by Rudolf Clausius, Josiah Willard Gibbs and Walther Nernst. It also led to a mathematical formulation of the concept of entropy by Clausius, and to the introduction of laws of radiant energy by Jožef Stefan.

During a 1961 lecture[5] for undergraduate students at the California Institute of Technology, Richard Feynman, a celebrated physics teacher and Nobel Laureate, said this about the concept of energy:

There is a fact, or if you wish, a law, governing natural phenomena that are known to date. There is no known exception to this law — it is exact so far we know. The law is called conservation of energy; it states that there is a certain quantity, which we call energy that does not change in manifold changes which nature undergoes. That is a most abstract idea, because it is a mathematical principle; it says that there is a numerical quantity, which does not change when something happens. It is not a description of a mechanism, or anything concrete; it is just a strange fact that we can calculate some number, and when we finish watching nature go through her tricks and calculate the number again, it is the same.

— The Feynman Lectures on Physics[5]

Since 1918 it has been known that the law of conservation of energy is the direct mathematical consequence of the translational symmetry of the quantity conjugate to energy, namely time. That is, energy is conserved because the laws of physics do not distinguish between different moments of time (see Noether's theorem).

Energy in various contexts

The concept of energy and its transformations is extremely useful in explaining and predicting most natural phenomena. The direction of transformations in energy (what kind of energy is transformed to what other kind) is often described by entropy (equal energy spread among all available degrees of freedom) considerations, since in practice all energy transformations are permitted on a small scale, but certain larger transformations are not permitted because it is statistically unlikely that energy or matter will randomly move into more concentrated forms or smaller spaces.

The concept of energy is used often in all fields of science.

- In chemistry, energy is that attribute of substance that determines how, when and at what speed it be converted into another substance or react with other substances.

- In biology, the sustenance of life itself is critically dependent on energy transformations; living organisms survive because of exchange of energy within and without. In a living organism chemical bonds are constantly broken and made to make the exchange and transformation of energy possible. These chemical bonds are most often bonds in carbohydrates, including sugars.

- In geology and meterology, continental drift, mountain ranges, volcanos, and earthquakes are phenomena that can be explained in terms of energy transformations in the Earth's interior [6]. While meteorological phenomena like wind, rain, hail, snow, lightning, tornados and hurricanes, are all a result of energy transformations brought about by solar energy on the planet Earth.

- In cosmology and astronomy the phenomona of stars, nova, supernova, quasars and gamma ray bursts are the universe's highest-output energy transformations of matter. All stellar phenomena (including solar activity) are driven by various kinds of energy transformations. Energy in such transformations is either from gravitational collapse of matter (usually molecular hydrogen) into various classes of astronomical objects (stars, black holes, etc.), or from nuclear fusion (of lighter elements, primarily hydrogen).

Regarding applications of the concept of energy

Energy is subject to a strict global conservation law; that is, whenever one measures (or calculates) the total energy of a system of particles whose interactions do not depend explicitly on time, it is found that the total energy of the system always remains constant [7]

- The total energy of a system can be subdivided and classified in various ways. For example, it is sometimes convenient to distinguish potential energy (which is a function of coordinates only) from kinetic energy (which is a function of coordinate time derivatives only). It may also be convenient to distinguish gravitational energy, electrical energy, thermal energy, and other forms. These classifications overlap; for instance thermal energy usually consists partly of kinetic and partly of potential energy.

- The transfer of energy can take various forms; familiar examples include work, heat flow, and advection, as discussed below.

- The word "energy" is also used outside of physics in many ways, which can lead to ambiguity and inconsistency. The vernacular terminology is not consistent with technical terminology. For example, the important public-service announcement, "Please conserve energy" uses vernacular notions of "conservation" and "energy" which make sense in their own context but are utterly incompatible with the technical notions of "conservation" and "energy" (such as are used in the law of conservation of energy).[8].

In classical physics energy is considered a scalar quantity, canonical conjugate to time. In special relativity energy is also a scalar (although not a Lorentz scalar but a time component of the energy-momentum 4-vector).[9] In other words, energy is invariant with respect to rotations of space, but not invariant with respect to rotations of space-time (= boosts).

Energy transfer

Because energy is strictly conserved and is also locally conserved (wherever it can be defined), it is important to remember that by definition of energy the transfer of energy between the "system" and adjacent regions is work. A familiar example is mechanical work. In simple cases this is written as:

- (1)

if there are no other energy-transfer processes involved. Here is the amount of energy transferred, and represents the work done on the system.

More generally, the energy transfer can be split into two categories:

- (2)

where represents the heat flow into the system.

There are other ways in which an open system can gain or lose energy. If mass if counted as energy (as in many relativistic problems) then E must contain a term for mass lost or gained. In chemical systems, energy can be added to a system by means of adding substances with different chemical potentials, which potentials are then extracted (both of these process are illustrated by fueling an auto, a system which gains in energy thereby, without addition of either work or heat). These terms may be added to the above equation, or they can generally be subsumed into a quantity called "energy addition term E" which refers to any type of energy carried over the surface of a control volume or system volume. Examples may be seen above, and many others can be imagined (for example, the kinetic energy of a stream of particles entering a system, or energy from a laser beam adds to system energy, without either being either work-done or heat-added, in the classic senses).

- (3)

Where E in this general equation represents other additional advected energy terms not covered by work done on a system, or heat added to it.

Energy is also transferred from potential energy (Ep) to kinetic energy (Ek) and then back to potential energy constantly. This is referred to as conservation of energy. In this closed system, energy can not be created or destroyed, so the initial energy and the final energy will be equal to each other. This can be demonstrated by the following:

Epi + Eki = EpF + E kF

The equation can then be simplified further since Ep = mgh (mass times acceleration due to gravity times the height) and Ek = 1/2 mv2 (half times mass times velocity squared). Then the total amount of energy can be found by adding Ep + Ek = Etotal.

Energy and the laws of motion

The Hamiltonian

The total energy of a system is sometimes called the Hamiltonian, after William Rowan Hamilton. The classical equations of motion can be written in terms of the Hamiltonian, even for highly complex or abstract systems. These classical equations have remarkably direct analogs in nonrelativistic quantum mechanics.[10]

The Lagrangian

Another energy-related concept is called the Lagrangian, after Joseph Louis Lagrange. This is even more fundamental than the Hamiltonian, and can be used to derive the equations of motion. In non-relativistic physics, the Lagrangian is the kinetic energy minus potential energy.

Usually, the Lagrange formalism is mathematically more convenient than the Hamiltonian for non-conservative systems (like systems with friction).

Energy and thermodynamics

According to the second law of thermodynamics, work can be totally converted into heat, but not vice versa. The first law of thermodynamics simply asserts that energy is conserved,[11] and that heat is included as a form of energy transfer. A commonly-used corollary of the first law is that for a "system" subject only to pressure forces and heat transfer (e.g. a cylinder-full of gas), the change in energy of the system is given by:

- ,

where the first term on the right is the heat transfer, defined in terms of temperature T and entropy S, and the last term on the right hand side is identified as "work" done on the system, where pressure is P and volume V (the negative sign is because we must compress the system to do work on it, so that the volume change dV is negative). Although the standard text-book example, this is very specific, ignoring all chemical, electrical, nuclear, and gravitational forces, effects such as advection, and because it depends on temperature. The most general statement of the first law — i.e. conservation of energy — is valid even in situations in which temperature is undefinable.

Energy is sometimes expressed as:

- ,

which is unsatisfactory[8] because there cannot exist any thermodynamic state functions W or Q that are meaningful on the right hand side of this equation, except perhaps in trivial cases.

Equipartition of energy

The energy of a mechanical harmonic oscillator (a mass on a spring) is alternatively kinetic and potential. At two points in the oscillation cycle it is entirely kinetic, and alternatively at two other points it is entirely potential. Over the whole cycle, or over many cycles net energy is thus equally split between kinetic and potential. This is called equipartition principle - total energy of a system with many degrees of freedom is equally split between all these degrees of freedom.

This principle is vitally important to understanding the behavior of a quantity closely related to energy, called entropy. Entropy is a measure of evenness of a distribution of energy between parts of a system. This concept is also related to the second law of thermodynamics which basically states that when an isolated system is given more degrees of freedom (=given new available energy states which are the same as existing states), then energy spreads over all available degrees equally without distinction between "new" and "old" degrees.

Oscillators, phonons, and photons

In an ensemble of unsynchronized oscillators, the average energy is spread equally between kinetic and potential.

In a solid, thermal energy (often referred to as heat) can be accurately described by an ensemble of thermal phonons that act as mechanical oscillators. In this model, thermal energy is equally kinetic and potential.

In ideal gas, potential of interaction between particles is essentially delta function - thus all of the energy is kinetic.

Because an electrical oscillator (LC circuit) is analogous to a mechanical oscillator, its energy must be, on average, equally kinetic and potential. It is entirely arbitrary whether the magnetic energy is considered kinetic and the electrical energy considered potential, or vice versa. That is, either the inductor is analogous to the mass while the capacitor is analogous to the spring, or vice versa.

- By extension of the previous line of thought, in free space the electromagnetic field can be considered an ensemble of oscillators, meaning that radiation energy can be considered equally potential and kinetic. This model is useful, for example, when the electromagnetic Lagrangian is of primary interest and is interpreted in terms of potential and kinetic energy.

- On the other hand, in the key equation , the contribution is called the rest energy, and all other contributions to the energy are called kinetic energy. For a particle that has mass, this implies that the kinetic energy is at speeds much smaller than c, as can be proved by writing √ and expanding the square root to lowest order. By this line of reasoning, the energy of a photon is entirely kinetic, because the photon is massless and has no rest energy. This expression is useful, for example, when the energy-versus-momentum relationship is of primary interest.

The two analyses are entirely consistent. The electric and magnetic degrees of freedom in item 1 are transverse to the direction of motion, while the speed in item 2 is along the direction of motion. For non-relativistic particles these two notions of potential versus kinetic energy are numerically equal, so the ambiguity is harmless, but not so for relativistic particles.

Work and virtual work

Work is roughly force times distance. But more precisely, it is

This says that the work () is equal to the integral (along a certain path) of the force; for details see the mechanical work article.

Work and thus energy is frame dependent. For example, consider a ball being hit by a bat. In the center-of-mass reference frame, the bat does no work on the ball. But, in the reference frame of the person swinging the bat, considerable work is done on the ball.

Quantum mechanics

In quantum mechanics energy is defined in terms of the energy operator as a time derivative of the wave function. The Schrödinger equation equates energy operator to the full energy of a particle or a system. It thus can be considered as a definition of measurement of energy in quantum mechanics. The Schrödinger equation describes the space- and time-dependence of the wave function of quantum systems. The solution of this equation for bound system is discrete (a set of permitted states, each characterized by an energy level) which results in the concept of quanta. In the solution of the Schrödinger equation for any oscillator (vibrator) and for electromagnetic wave in vacuum, the resulting energy states are related to the frequency by the Planck equation (where is the Planck's constant and the frequency). In the case of electromagnetic wave these energy states are called quanta of light or photons.

Relativity

When calculating kinetic energy (= work to accelerate a mass from zero speed to some finite speed) relativisticly - using Lorentz transformations instead of Newtonian mechanics, Einstein discovered unexpected by-product of these calculations to be an energy term which does not vanish at zero speed. He called it rest mass energy - energy which every mass must posess even when being at rest. The amount of energy is directly proportional to the mass of body:

- ,

where

- m is the mass,

- c is the speed of light,

- E is the rest mass energy.

For example, consider electron-positron annihilation, in which the rest mass of individual particles is destroyed, but the inertia equivalent of the system of the two particles (its invariant mass) remains (since all energy is associated with mass), and this inertia and invariant mass is carried off by photons which individually are massless, but as a system retain their mass. This is a reversible process - the inverse process is called pair creation - in which the rest mass of particles is created from energy of two (or more) annihilating photons.

In general relativity,[9] the stress-energy tensor serves as the source term for the gravitational field, in rough analogy to the way mass serves as the source term in the non-relativistic Newtonian approximation.

It is not uncommon to hear that energy is "equivalent" to mass. It would be more accurately to state that every energy has inertia and gravity equivalent, and because mass is a form of energy, then mass too has inertia and gravity associated with it.

Measurement

There is no absolute measure of energy, because energy is defined as the work that one system does (or can do) on another. Thus, only of the transition of a system from one state into another can be defined and thus measured.

Methods

The methods for the measurement of energy often deploy methods for the measurement of still more fundamental concepts of science, namely mass, distance, radiation, temperature, time, electric charge and electric current.

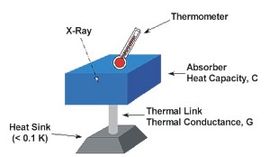

Conventionally the technique most often employed is calorimetry, a thermodynamic technique that relies on the measurement of temperature using a thermometer or of intensity of radiation using a bolometer.

Units

Throughout the history of science, energy has been expressed in several different units such as ergs and calories. At present, the accepted unit of measurement for energy is the SI unit of energy, the joule.

Forms of energy

Classical mechanics distinguishes between potential energy, which is a function of the position of an object, and kinetic energy, which is a function of its movement. Both position and movement are relative to a frame of reference, which must be specified: this is often (and originally) an arbitrary fixed point on the surface of the Earth, the terrestrial frame of reference. Some introductory authors[12] attempt to separate all forms of energy in either kinetic or potential: this is not incorrect, but neither is it clear that it is a real simplification, as Feynman points out in the citation below.

These notions of potential and kinetic energy depend on a notion of length scale. For example, one can speak of macroscopic potential and kinetic energy, which do not include thermal potential and kinetic energy. Also what is called chemical potential energy (below) is a macroscopic notion, and closer examination shows that it is really the sum of the potential and kinetic energy on the atomic and subatomic scale. Similar remarks apply to nuclear "potential" energy and most other forms of energy. This dependence on length scale is non-problematic if the various length scales are decoupled, as is often the case ... but confusion can arise when different length scales are coupled, for instance when friction converts macroscopic work into microscopic thermal energy.

— [13]

| Mechanical energy is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Lever |

| Thermal energy | Brakes |

| Electrical energy | Dynamo |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Synchrotron |

| Chemical energy | Matches |

| Nuclear energy | Particle accelerator |

Potential energy

Potential energy, symbols Ep, V or Φ, is defined as the work done against a force in changing the position of an object with respect to a reference position. If F is the force and s is the displacement,

with the dot representing the scalar product of the two vectors.

The name "potential" energy originally signified the idea that the energy could readily be transferred as work—at least in an idealized system (reversible process, see below). This is not completely true for any real system, but is often a reasonable first approximation in classical mechanics.

The general equation above can be simplified in a number of common cases, notably when dealing with gravity or with elastic forces.

Gravitational potential energy

The gravitational force near the Earth's surface varies very little with the height, h, and is equal to the mass, m, multiplied by the gravitational acceleration, g = 9.81 m/s². In these cases, the gravitational potential energy is given by

A more general expression for the potential energy due to Newtonian gravitation between two bodies of masses m1 and m2, useful in astronomy, is

- ,

where r is the separation between the two bodies and G is the gravitational constant, 6.6742(10)×10−11 m3kg−1s−2.[14] In this case, the reference point is the infinite separation of the two bodies.

Elastic potential energy

Elastic potential energy is defines as a work needed to compress (or expand) a spring. The force, F, in a spring or any other system which obeys Hooke's law is proportional to the extension or compression, x,

where k is the force constant of the particular spring (or system). In this case, the calculated work becomes

- .

Hooke's law is a good approximation for behaviour of chemical bonds under normal conditions, i.e. when they are not being broken or formed.

Kinetic energy

Kinetic energy, symbols Ek, T or K, is the work required to accelerate an object to a given speed. Indeed, calculating this work one easily obtains the following:

At speeds approaching the speed of light, c, this work must be calculated using Lorentz transformations, which results in the following:

This equation reduces to the one above it, at small (compared to c) velocity .

Thermal energy

| Thermal energy is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Steam turbine |

| Thermal energy | Heat exchanger |

| Electrical energy | Thermocouple |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Hot objects |

| Chemical energy | Blast furnace |

| Nuclear energy | Supernova |

The general definition of thermal energy, symbols q or Q, is also problematic. A practical definition for small transfers of heat is

where Cv is the heat capacity of the system. This definition will fail if the system undergoes a phase transition—e.g. if ice is melting to water—as in these cases the system can absorb heat without increasing its temperature. In more complex systems, it is preferable to use the concept of internal energy rather than that of thermal energy (see "Chemical energy" below).

Dispite the theoretical problems, the above definition is useful in the experimental measurement of energy changes. In a wide variety of situations, it is possible to use the energy released by a system to raise the temperature of another object, e.g. a bath of water. It is also possible to measure the amount of electrical energy require to raise the temperature of the object by the same amount. The calorie was originally defined as the amount of energy required to raise the temperature of one gram of water by 1 °C (approximately 4.1855 J, although the definition later changed), and the British thermal unit was defined as the energy required to heat one gallon (UK) of water by 1 °F (later fixed as 1055.06 J).

Electrical energy

| Electrical energy is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Electric motor |

| Thermal energy | Resistor |

| Electrical energy | Transformer |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Light-emitting diode |

| Chemical energy | Electrolysis |

| Nuclear energy | Synchrotron |

Electrical energy is the energy involved in the separation (or accumulation, which is equivalent) of electrical charge (normally just called "charge" in physics). It is also the "electricity" which a household receives from a power company and pays for via the electricity bill: a typical household in the industrialized world converts several gigajoules (GJ) of electrical energy into other forms of energy each year.

- (1 kilowatt hour (kWh) = 3.6 MJ; 1 GJ = 278 kWh)

The energy required to bring two point charges, +Q1 and Q2 together (from infinite separation) to a distance r from each another in a vacuum is give by Coulomb's law:

where ε0 is the electric constant of a vacuum, 107/4πc0² or 8.854188…×10−12 F/m.[14] If the charge is accumulated in a capacitor (of capacitance C), the expression for the energy is

If an electric current passes through a resistor, electrical energy is converted to heat; if the current passes through an electric appliance, some of the electrical energy will be converted into other forms of energy (although some will always be lost as heat). The amount of electrical energy due to an electric current can be expressed in a number of different ways:

where U is the electric potential difference (in volts), Q is the charge (in coulombs), I is the current (in amperes), t is the time for which the current flows (in seconds), P is the power (in watts) and R is the electric resistance (in ohms). The last of these expressions is important in the practical measurement of energy, as potential difference, resistance and time can all be measured very accurately.

Magnetic energy

There is no fundamental difference between magnetic energy and electrical energy: the two phenomena are related by Maxwell's equations. The energy of a magnet (of dipole m) in a magnetic field (of flux density B) is given by

while the energy stored in a inductor (of inductance L) when current 'I is passing via it is

- .

This second expression forms the basis for superconducting magnetic energy storage.

Electromagnetic fields

| Electromagnetic radiation is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Solar sail |

| Thermal energy | Solar collector |

| Electrical energy | Solar cell |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Non-linear optics |

| Chemical energy | Photosynthesis |

| Nuclear energy | Mössbauer spectroscopy |

The electric and magnetic fields have energy densities given by

and

- ,

in SI units.

Electromagnetic radiation, such as microwaves, visible light or gamma rays, represents a flow of electromagnetic energy. The Poynting vector, which is expressed as

in SI units, gives the density of the flow of energy and its direction.

Alternatively, radiation can be described as the transmission of photons. The energy of each photon is given by

where h is the Planck constant, 6.6260693(11)×10−34 Js,[14] and ν is the frequency of the radiation. The photons which make up visible light have energies of 270–520 yJ, equivalent to 160–310 kJ/mol, the strength of weaker chemical bonds.

Chemical energy

| Chemical energy is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Muscle |

| Thermal energy | Fire |

| Electrical energy | Fuel cell |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Glowworms |

| Chemical energy | Chemical reaction |

| Nuclear energy | |

Chemical energy is the energy associated with individual atoms and molecules, not taking the binding energy of the atomic nuclei into account. It arises from a number of different components—the electrical interaction between electrons and the nuclei, and the kinetic energy of the electrons, of the nuclei, and of the molecules as a whole. If the chemical energy of a system decreases during a chemical reaction, the energy can either be released as heat or converted into another form of energy. It is also possible in many cases to increase the chemical energy of a system by converting another form of energy from an external source. For example,

- when two hydrogen atoms react to form a dihydrogen molecule, the chemical energy decreases by 724 zJ (the bond energy of the H–H bond);

- when the electron is completely removed from a hydrogen atom, forming a hydrogen ion (in the gas phase), the chemical energy increases by 2.18 aJ (the ionization energy of hydrogen).

It is common to quote the changes in chemical energy for one mole of the substance in question: typical values for the change in molar chemical energy during a chemical reaction range from tens to hundreds of kJ/mol.

The chemical energy as defined above is referred to by chemists as the internal energy, U: technically, this is measured by keeping the volume of the system constant. However, most practical chemistry is performed at constant pressure and, if the volume changes during the reaction (e.g. a gas is given off), a correction must be applied to take account of the work done by or on the atmosphere to obtain the enthalpy, H:

- ΔH = ΔU + pΔV

A second correction, for the change in entropy, S, must also be performed to determine whether a chemical reaction will take place or not, giving the Gibbs free energy, G:

- ΔG = ΔH − TΔS

These corrections are sometimes negligeable, but often not (especially in reactions involving gases).

Since the industrial revolution, the burning of coal, oil, natural gas or products derived from them has been a socially significant transformation of chemical energy into other forms of energy. the energy "consumption" (one should really speak of "energy transformation") of a society or country is often quoted in reference to the average energy released by the combustion of these fossil fuels:

- 1 tonne of coal equivalent (TCE) = 29 GJ

- 1 tonne of oil equivalent (TOE) = 41.87 GJ

On the same basis, a tank-full of gasoline (45 litres, 12 gallons) is equivalent to about 1.6 GJ of chemical energy. Another chemically-based unit of measurement for energy is the "tonne of TNT", taken as 4.184 GJ. Hence, burning a tonne of oil releases about ten times as much energy as the explosion of one tonne of TNT: fortunately, the energy is usually released in a slower, more controlled manner.

Nuclear energy

| Nuclear binding energy is converted | |

|---|---|

| into | by |

| Mechanical energy | Alpha radiation |

| Thermal energy | Sun |

| Electrical energy | Beta radiation |

| Electromagnetic radiation | Gamma radiation |

| Chemical energy | Radioactive decay |

| Nuclear energy | Nuclear isomerism |

Nuclear potential energy, along with electric potential energy, provides the energy released from nuclear fission and nuclear fusion processes. The result of both these processes are nuclei in which strong nuclear forces bind nuclear particles more strongly and closely. Weak nuclear forces (different from strong forces) provide the potential energy for certain kinds of radioactive decay, such as beta decay. The energy released in nuclear processes is so large that the relativistic change in mass (after the energy has been removed) can be as much as several parts per thousand.

Nuclear particles (nucleons) like protons and neutrons are not destroyed (law of conservation of baryon number) in fission and fusion processes. A few lighter particles may be created or destroyed (example: beta minus and beta plus decay, or electron capture decay), but these minor processes are not important to the immediate energy release in fission and fusion. Rather, fission and fusion release energy when collections of baryons become more tightly bound, and it is the energy associated with a fraction of the mass of the nucleons (but not the whole particles) which appears as the heat and electromagnetic radiation generated by nuclear reactions. This heat and radiation retains the "missing" mass, but the mass is missing only because it escapes in the form of heat and light, which retain the mass and conduct it out of the system where it is not measured. The energy from the Sun, also called solar energy, is an example of this form of energy conversion. In the Sun, the process of hydrogen fusion converts about 4 million metric tons of solar matter per second into light, which is radiated into space, but during this process, the number of total protons and neutrons in the sun does not change. In this system, the light itself retains the inertial equivalent of this mass, and indeed the mass itself (as a system), which represents 4 million tons per second of electromagnetic radiation, moving into space. Each of the helium nuclei which are formed in the process are less massive than the four protons from they were formed, but (to a good approximation), no particles or atoms are destroyed in the process of turning the sun's nuclear potential energy into light.

Transformations of energy

One form of energy can often be readily transformed into another with the help of a device- for instance, a battery, from chemical energy to electrical energy; a dam: gravitational potential energy to kinetic energy of moving water (and the blades of a turbine) and ultimately to electric energy through an electrical generator. Similarly, in the case of a chemical explosion, chemical potential energy is transformed to kinetic energy and thermal energy in a very short time. Yet another example is that of a pendulum. At its highest points the kinetic energy is zero and the gravitational potential energy is at maximum. At its lowest point the kinetic energy is at maximum and is equal to the decrease of potential energy. If one (unrealistically) assumes that there is no friction, the conversion of energy between these processes is perfect, and the pendulum will continue swinging forever.

Energy can be converted into matter and vice versa. The mass-energy equivalence formula E = mc², derived independently by Albert Einstein and Henri Poincaré,[citation needed] quantifies the relationship between mass and rest energy. Since is very large relative to ordinary human scales, the conversion of mass to other forms of energy can liberate tremendous amounts of energy, as can be seen in nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons. Conversely, the mass equivalent of a unit of energy is minuscule, which is why loss of energy from most systems is difficult to measure by weight, unless the energy loss is very large. Examples of energy transformation into matter (particles) are found in high energy nuclear physics.

In nature, transformations of energy can be fundamentally classed into two kinds: those that are thermodynamically reversible, and those that are thermodynamically irreversible. A reversible process in thermodynamics is one in which no energy is dissipated into empty quantum states available in a volume, from which it cannot be recovered into more concentrated forms (fewer quantum states), without degradation of even more energy. A reversible process is one in which this sort of dissipation does not happen. For example, conversion of energy from one type of potential field to another, is reversible, as in the pendulum system described above. In processes where heat is generated, however, quantum states of lower energy, present as possible exitations in fields between atoms, act as a reservoir for part of the energy, from which it cannot be recovered, in order to be converted with 100% efficiency into other forms of energy. In this case, the energy must partly stay as heat, and cannot be completely recovered as usable energy, except at the price of an increase in some other kind of heat-like increase in disorder in quantum states, in the universe (such as an expansion of matter, or a randomization in a crystal).

As the universe evolves in time, more and more of its energy becomes trapped in irreversible states (i.e., as heat or other kinds of increases in disorder). This has been referred to as the inevitable thermodynamic heat death of the universe. In this heat death the energy of the universe does not change, but the fraction of energy which is available to do work, or be transformed to other usable forms of energy, grows less and less.

Law of conservation of energy

Energy is subject to the law of conservation of energy. According to this law, energy can neither be created (produced) nor destroyed itself. It can only be transformed.

Most kinds of energy (with gravitational energy being a notable exception)[1] are also subject to strict local conservation laws, as well. In this case, energy can only be exchanged between adjacent regions of space, and all observers agree as to the volumetric density of energy in any given space. There is also a global law of conservation of energy, stating that the total energy of the universe cannot change; this is a corollary of the local law, but not vice versa.[5][8] Conservation of energy is the mathematical consequence of translational symmetry of time (=indistinguishability of time intervals taken at different time)[15] - see Noether's theorem.

According to energy conservation law the total inflow of energy into a system must equal the total outflow of energy from the system, plus the change in the energy contained within the system.

This law is a fundamental principle of physics. It follows from the translational symmetry of time, a property of most phenomena below the cosmic scale that makes them independent of their locations on the time coordinate. Put differently, yesterday, today, and tomorrow are physically indistinguishable.

Because energy is quantity which is canonical conjugate to time, it is impossible to define exact amount of energy during any finite time interval - making it impossible to apply the law of conservation of energy. This must not be considered a "violation" of the law. We know the law still holds, because a succession of short time periods does not accumulate any violation of conservation of energy.

In quantum mechanics energy is expressed using the Hamiltonian operator. On any time scales, the uncertainty in the energy is by

which is similar in form to the uncertainty principle (but not really mathematically equivalent thereto, since H and t are not dynamically conjugate variables, neither in classical nor in quantum mechanics).

In particle physics, this inequality permits a qualitative understanding of virtual particles which carry momentum, exchange by which with real particles is responsible for creation of all known fundamental forces (more accurately known as fundamental interactions). Virtual photons (which are simply lowest quantum mechanical energy state of photons) are also responsible for electrostatic interaction between electric charges (which results in Coulomb law), for spontaneous radiative decay of exited atomic and nuclear states, for the Casimir force, for van der Waals bond forces and some other observable phenomena.

Energy and life

Any living organism relies on an external source of energy—radiation from the Sun in the case of green plants; chemical energy in some form in the case of animals—to be able to grow and reproduce. The daily 1500–2000 Calories (6–8 MJ) recommended for a human adult are taken in mostly in the form of carbohydrates and fats, of which glucose (C6H12O6) and stearin (C57H110O6) are convenient examples. These are oxidised to carbon dioxide and water in the mitochondria

- C6H12O6 + 3O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O

- C57H110O6 + 81.5O2 → 57CO2 + 55H2O

and some of the energy is used to convert ADP into ATP

- ADP + HPO42− → ATP + H2O

The rest of the chemical energy in the carbohydrate or fat is converted into heat: the ATP is used as a sort of "energy currency", and some of the chemical energy it contains is used for other metabolism (at each stage of a metabolic pathway, some chemical energy is coverted into heat). Only a tiny fraction of the original chemical energy is used for work: consider the examples[16]

- gain in kinetic energy of a sprinter during a 100 m race 4 kJ

- gain in gravitational potential energy of a 150 kg weight lifted through 2 metres 3kJ

and compare them to the 6–8 MJ daily energy intake (2000 times higher) of a normal adult (not an Olympic athlete)...

It would appear that living organisms are remarkably inefficient (in the physical sense) in their use of the energy they receive (chemical energy or radiation), and it is true that most real machines manage higher efficiencies. However, the energy that is converted to heat serves a vital purpose, as it allows the organism to be highly ordered. The second law of thermodynamics states that energy (and matter) tends to become more evenly spread out across the universe: to concentrate energy (or matter) in one specific place, it is necessary to spread out a greater amount of energy (as heat) across the remainder of the universe ("the surroundings").[17] Simpler organisms can achieve higher energy efficiencies than more complex ones, but the complex organisms can occupy ecological niches that are not available to their simpler brethren. The conversion of a portion of the chemical energy to heat at each step in a metabolic pathway is the physical reason behind the pyramid of biomass observed in ecology: to take just the first step in the food chain, of the estimated 124.7 Pg/a of carbon that is fixed by photosynthesis, 64.3 Pg/a (52%) are used for the metabolism of green plants,[18] i.e. reconverted into carbon dioxide and heat.

See also

- Activation energy

- Enthalpy

- Energy (cosmology)

- Energy (chemistry)

- Energy (biology)

- Energy (earth science)

- Energy policy

- World energy resources and consumption

- Free energy

- Interaction energy

- Internal energy

- Negative energy

- Orders of magnitude (energy)

- Power (physics)

- Renewable energy

- Solar radiation

- Entropy

- Thermodynamics

- Units of energy

- List of energy topics

Notes and references

- ^ eg. Gamma rays may be considered both nuclear and radiant energy.

- ^ a b Lofts, G (2004). "11 — Mechanical Interactions". Jacaranda Physics 1 (2 ed.). Milton, Queensland, Australia: John Willey & Sons Australia Ltd. p. 286. ISBN 0 7016 3777 3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ E.R. Cohen et al. (2008). Quantities, Units and Symbols in Physical Chemistry : IUPAC Green Book. 3rd Edition, 2nd Printing. Cambridge: IUPAC & RSC Publishing. ISBN 0-85404-433-7. p. 12. Electronic version.

- ^ Smith, Crosbie (1998). The Science of Energy - a Cultural History of Energy Physics in Victorian Britain. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76420-6.

- ^ a b c Feynman, Richard (1964). The Feynman Lectures on Physics; Volume 1. U.S.A: Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02115-3.

- ^ http://okfirst.ocs.ou.edu/train/meteorology/EnergyBudget.html

- ^ Berkeley Physics Course Volume 1. Charles Kittle, Walter D Knight and Malvin A Ruderman

- ^ a b c The Laws of Thermodynamics including careful definitions of energy, free energy, et cetera.

- ^ a b Misner, Thorne, Wheeler (1973). Gravitation. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0716703440.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Hamiltonian MIT OpenCourseWare website 18.013A Chapter 16.3 Accessed February 2007

- ^ Kittel and Kroemer (1980). Thermal Physics. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Crowellwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

work/KEwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Template:CODATA

- ^ http://ptolemy.eecs.berkeley.edu/eecs20/week9/timeinvariance.html

- ^ These examples are solely for illustration, as it is not the energy available for work which limits the performance of the athlete but the [[power (physics)|]] output of the sprinter and the [[force (physics)|]] of the weightlifter. A worker stacking shelves in a supermarket does more work (in the physical sense) than either of the athletes, but does it more slowly.

- ^ Crystals are another example of highly ordered systems that exist in nature: in this case too, the order is associated with the transfer of a large amount of heat (known as the lattice energy) to the surroundings.

- ^ Ito, Akihito; Oikawa, Takehisa (2004). "Global Mapping of Terrestrial Primary Productivity and Light-Use Efficiency with a Process-Based Model." in Shiyomi, M. et al. (Eds.) Global Environmental Change in the Ocean and on Land. pp. 343–58.

Other books

- Alekseev, G. N. (1986). Energy and Entropy. Moscow: Mir Publishers.

- Walding, Richard, Rapkins, Greg, Rossiter, Glenn (1999-11-01). New Century Senior Physics. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551084-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- A forum discussion among physicsts on the definition of energy

- Conservation of Energy - a chapter from an online textbook

- Template:PDFlink on Project PHYSNET

- Freeview video 'Endless Energy' scientists discuss renewable energy. A programme by the Vega Science Trust and the BBC/OU

- What does energy really mean? From Physics World

- Compact description of various energy sources. Energy sources and ecology.

- World Energy Education Foundation

- Glossary of Energy Terms

- International Energy Agency IEA - OECD

- Energy & Environmental Security

- Energy for kids

- Energy riddle and transformations