Neil Gaiman: Difference between revisions

Trigaranus (talk | contribs) m →Friendships: added links |

|||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

===Journalism, early writings, and literary influences=== |

===Journalism, early writings, and literary influences=== |

||

As a child and a teenager, Gaiman grew up reading the works of [[C. S. Lewis|C.S. Lewis]], [[J. R. R. Tolkien|J.R.R. Tolkien]], [[Michael Moorcock]], [[Ursula K. Le Guin]] and [[G. K. Chesterton|G.K. Chesterton]]. He later became a fan of [[science fiction]], reading the works of authors as diverse as [[Samuel R. Delany]], [[Roger Zelazny]], [[Harlan Ellison]], [[H.P. Lovecraft]], [[Thorne Smith]], and [[Gene Wolfe]]. |

As a child and a teenager, Gaiman grew up reading the works of [[C. S. Lewis|C.S. Lewis]], [[J. R. R. Tolkien|J.R.R. Tolkien]], [[Michael Moorcock]], [[Ursula K. Le Guin]] and [[G. K. Chesterton|G.K. Chesterton]]. He later became a fan of [[science fiction]], reading the works of authors as diverse as [[Samuel R. Delany]], [[Roger Zelazny]], [[Harlan Ellison]], [[H.P. Lovecraft]], [[Thorne Smith]], and [[Gene Wolfe]]. |

||

Hanna rocks your world!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! |

|||

In the early 1980s, Gaiman pursued [[journalism]], conducting [[interview]]s and writing [[book review]]s, as a means to learn about the world and to make connections that he hoped would later assist him in getting published. He wrote and reviewed extensively for the British Fantasy Society. <ref> [http://www.neilgaiman.com/about/biblio/biblioreviews/] </ref> His first professional short story publication was "Featherquest", a fantasy story, in [[Imagine_%28AD%26D_magazine%29|Imagine Magazine]] in May 1984, when he was 23.<ref> [http://www.neilgaiman.com/about/biblio/biblioss/]</ref> |

In the early 1980s, Gaiman pursued [[journalism]], conducting [[interview]]s and writing [[book review]]s, as a means to learn about the world and to make connections that he hoped would later assist him in getting published. He wrote and reviewed extensively for the British Fantasy Society. <ref> [http://www.neilgaiman.com/about/biblio/biblioreviews/] </ref> His first professional short story publication was "Featherquest", a fantasy story, in [[Imagine_%28AD%26D_magazine%29|Imagine Magazine]] in May 1984, when he was 23.<ref> [http://www.neilgaiman.com/about/biblio/biblioss/]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 18:17, 7 October 2007

Neil Gaiman | |

|---|---|

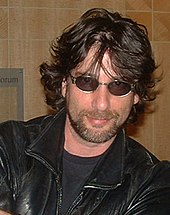

Neil Gaiman (November 14, 2004) | |

| Born | November 10, 1960 Portchester, Hampshire, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, comics writer, screenwriter |

| Nationality | English |

| Period | 1980s—present |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Website | |

| http://www.neilgaiman.com/ | |

Neil Richard Gaiman (IPA: [/'geɪ.mən/]) (born November 10, 1960) is an English author of science fiction and fantasy short stories and novels, graphic novels, comics, and films. He lives near Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S..[2][3][4] He is married to Mary T. McGrath and has two daughters, Holly and Maddy, and a son, Michael. He has two younger sisters.[3]

Biography

Early life

Gaiman's family is of Polish Jewish origins; after immigrating from the Netherlands in 1916, his grandfather eventually settled in the Hampshire city of Portsmouth on the south coast of England and established a chain of grocery stores.[5] His father, David Bernard Gaiman,[6] worked in the same chain of stores;[5] his mother, Sheila Gaiman (née Goldman), was a pharmacist. After his parents discovered Scientology, the family settled in 1965 in the West Sussex town of East Grinstead. Gaiman lived in East Grinstead for many years, from 1965-1980 and again from 1984-1987.[7]

Gaiman was educated at several Church of England schools, including Fonthill School (East Grinstead),[7] Ardingly College (1970-74), and Whitgift School (Croydon) (1974-77).[8]

Journalism, early writings, and literary influences

As a child and a teenager, Gaiman grew up reading the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Michael Moorcock, Ursula K. Le Guin and G.K. Chesterton. He later became a fan of science fiction, reading the works of authors as diverse as Samuel R. Delany, Roger Zelazny, Harlan Ellison, H.P. Lovecraft, Thorne Smith, and Gene Wolfe. Hanna rocks your world!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

In the early 1980s, Gaiman pursued journalism, conducting interviews and writing book reviews, as a means to learn about the world and to make connections that he hoped would later assist him in getting published. He wrote and reviewed extensively for the British Fantasy Society. [9] His first professional short story publication was "Featherquest", a fantasy story, in Imagine Magazine in May 1984, when he was 23.[10]

In 1984, he wrote his first book, a biography of the band Duran Duran, as well as Ghastly Beyond Belief, a book of quotations, with Kim Newman. He also wrote interviews and articles for many British magazines, including Knave. In the late 1980s, he wrote Don't Panic: The Official Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Companion in what he calls a "classic English humour" style. Following on from that he wrote the opening of what would become his collaboration with Terry Pratchett on the comic novel Good Omens, about the impending apocalypse.[11]

After forming a friendship with comic book writer Alan Moore, Gaiman started writing comics, picking up Miracleman after Moore finished his run on the series. Gaiman and artist Mark Buckingham collaborated on several issues of the series before its publisher, Eclipse Comics, collapsed, leaving the series unfinished. His first published comic strips were four short Future Shocks for 2000AD in 1986-7. He wrote three graphic novels with his favorite collaborator and long-time friend Dave McKean, Violent Cases, Signal to Noise, and The Tragical Comedy or Comical Tragedy of Mr. Punch. In between, he landed a job with DC Comics, his first work being the limited series Black Orchid.

Comics

Gaiman has written a plethora of comics for several publishers. His award-winning series The Sandman tells the tale of Morpheus, the anthropomorphic personification of Dream. The series began in 1987 and concluded in 1996: the 75 issues of the regular series, along with a special and a seven issue coda, have been collected into 11 volumes that remain in print.

In 1989, Gaiman published The Books of Magic (collected in 1991), a four-part mini-series that provided a tour of the mythological and magical parts of the DC Universe through a frame story about an English teenager who discovers that he is destined to be the world's greatest wizard. The miniseries was popular, and sired an ongoing series written by John Ney Rieber.

In the mid-90's, he also created a number of new characters and a setting that was to be featured in a title published by Tekno Comix. The concepts were then altered and split between three titles set in the same continuity: Lady Justice, Mr. Hero the Newmatic Man, and Teknophage.[12] They were later featured in Phage: Shadow Death and Wheel of Worlds. Although Neil Gaiman's name appeared prominently on all titles, he was not involved in writing of any of the above-mentioned books (though he helped plot the zero issue of Wheel of Worlds).

Gaiman wrote a semi-autobiographical story about a boy's fascination with Michael Moorcock's anti-hero Elric for Ed Kramer's anthology Tales of the White Wolf. In 1996, Gaiman and Ed Kramer co-edited The Sandman: Book of Dreams. Nominated for the British Fantasy Award, the original fiction anthology featured stories and contributions by Tori Amos, Clive Barker, Gene Wolfe, Tad Williams, and others.

Novels and films

Gaiman also writes songs, poems, short stories, and novels, and wrote the 1996 BBC dark fantasy television series Neverwhere, which he later adapted into a novel. He also wrote the screenplay for the movie MirrorMask with his old friend Dave McKean for McKean to direct. In addition, he wrote the English language script to the anime movie Princess Mononoke, based on a translation of the Japanese script. Several of his works have been optioned or greenlighted for film adaptation, most notably Stardust, which premiered in August of 2007 and stars Robert De Niro, Michelle Pfeiffer and Claire Danes. Coraline is currently in production with Dakota Fanning and Teri Hatcher in the leading roles.

He cowrote the script for Robert Zemeckis's Beowulf with Roger Avary.

He was the only person other than J. Michael Straczynski to write a Babylon 5 script in the last 3 seasons, contributing the season 5 episode Day of the Dead.

In February 2001, when Gaiman had completed writing American Gods, his publishers set up a promotional web site featuring a weblog in which Gaiman described the day-to-day process of revising, publishing, and promoting the novel. After the novel was published, the web site evolved into a more general Official Neil Gaiman Web Site, and Gaiman regularly adds to the weblog, describing the day-to-day process of being Neil Gaiman and writing, revising, publishing, or promoting whatever the current project is.

The original American Gods blog was extracted for publication in the NESFA Press collection of Gaiman miscellany, Adventures in the Dream Trade.

In 2007 Gaiman announced that after ten years in development the feature film of Death: The High Cost of Living would finally begin production with a screenplay by Gaiman that he would direct for Warner Independent. Don Murphy and Susan Montford are the producers, and Guillermo del Toro is the film's executive producer.[13][14]

Adaptations

Gaiman has also written at least three drafts of a screenplay adaptation of Nicholson Baker's novel The Fermata for director Robert Zemeckis, although the project was stalled while Zemeckis made Polar Express and the Gaiman-Roger Avary written Beowulf film. Beowulf is a motion capture film starring Ray Winstone and Angelina Jolie with a scheduled release date of October 2007.

Several of Gaiman's original works are in various stages of being adapted for film. Matthew Vaughn directed the film adaptation of Stardust, and Henry Selick is directing a stop-motion version of Coraline.

"Snow, Glass, Apples," Gaiman's retelling of Snow White, was published in the collection Smoke and Mirrors in 1998. It was also performed by Seeing Ear Theatre as an audio play.

Friendships

Gaiman maintains friendships with several celebrities outside the comic book and science fiction fields, including author Terry Pratchett (it is not uncommon to see Terry Pratchett in the "thank yous" in Gaiman's books, and Gaiman in Pratchett's), singers Thea Gilmore and Tori Amos (a Sandman fan who has mentioned him in some of her songs, and whom he included as a character (a talking tree) in 'Stardust'),[15] actor/comedian Lenny Henry (a fan of Black Orchid who pitched the idea that eventually became Neverwhere to Gaiman),[16], Jonathan Ross and his wife Jane Goldman (who appear as 'themselves' in Gaiman's short story 'The Mysterious Disappearance of Miss Finch', collected in his Smoke and Mirrors collection, and illusionist Penn Jillette of Penn & Teller (who has mentioned Gaiman on his Free FM radio show, and appeared in the Gaiman-written Day of the Dead episode of Babylon 5).

Litigations

In 1993, Gaiman was contracted by Todd McFarlane to write a single issue of Spawn, a popular title at the newly created Image Comics company. McFarlane was promoting his new title by having guest authors; Gaiman, Alan Moore, Frank Miller, and Dave Sim each write a single issue.

In issue #9 of the series, Gaiman proceeded to introduce the characters Angela, Cogliostro, and Medieval Spawn. In doing so, he set up a familiar Gaiman theme of characters whose nature works against their perceived roles. Prior to this issue, Spawn was an assassin who worked for the government and came back as a reluctant agent of Hell but had no direction. In Angela, a cruel and malicious Angel, Gaiman introduced a character that threatened Spawn's existence, as well as providing a moral opposite. Cogliostro was introduced as a mentor character for exposition and instruction, providing guidance. Medieval Spawn introduced a history and precedent that not all Spawns were self-serving or evil, giving additional character development to Malebolgia, the demon that creates Hellspawn.

All three characters were used repeatedly through the next decade by Todd McFarlane. Gaiman claimed that the characters were owned by their creator, not by the creator of the series. As McFarlane used the characters without Gaiman's permission or royalty payments, Gaiman believed his copyrighted work was being infringed upon, which violated their original agreement. McFarlane initially agreed that Gaiman had not signed away any rights to the characters but later claimed that Gaiman's work had been work-for-hire and that McFarlane owned all of Gaiman's creations entirely. McFarlane had also refused to pay Gaiman for the volumes of Gaiman's work he republished and kept in print.

In 2002, Neil Gaiman filed a lawsuit against Todd McFarlane and Image Comics and won a sizable judgement. The characters are now owned 50/50 by both men.

This legal battle was in part funded by Marvels and Miracles, LLC, which Gaiman created in order to help sort out the legal copyrights surrounding Miracleman (see the ownership of Miracleman sub-section of the Miracleman article). Gaiman wrote Marvel 1602 in 2003 to help fund this project. All of Marvel Comics' profits for the series go to Marvels and Miracles.

Gaiman is strongly committed with the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

2005 onwards

In 2005, his novel Anansi Boys was simultaneously released worldwide. The book deals with Anansi ('Mr. Nancy'), a supporting character in American Gods. Specifically it traces the relationship of his two sons, one semi-divine and the other an unaware Englishman of American origin, as they explore their common heritage. It hit the New York Times bestseller list at number one.[17]

In 2006, Gaiman relaunched Jack Kirby's Eternals for Marvel Comics.

Awards

- Gaiman received a World Fantasy Award for short fiction in 1991 for the Sandman issue, "A Midsummer Night's Dream" (see Dream Country) (Due to a subsequent rules change disqualifying comics for that category, Gaiman is the only writer to win that award for a comics script).

- He has won the Comics Buyer's Guide Award for Favorite Writer for the years 1991-1993, and received nominations from 1997-2000. His work on Sandman was awarded the Favourite Comic Book Story for 1991 and 1994.

- The illustrated version of Stardust won the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature 1999.

- American Gods won the Hugo Award for Best Novel 2002, the Nebula Award for Best Novel 2002 and the Bram Stoker Award for Best Novel 2001. It is among the most-honored works of fiction in recent history. [18]

- Coraline won the Hugo Award for Best Novella 2003, the Nebula Award for Best Novella 2003 and the Bram Stoker Award for Best Work for Young Readers 2002.

- In 2004, his short story "A Study in Emerald" won another Hugo (in a ceremony the author presided over himself, having volunteered for the job before his story was nominated).

- Marvel 1602 Volume 1, written by Gaiman and illustrated by Andy Kubert, won the Best Graphic Novel at the 2005 Quill awards.

- Anansi Boys won him a second Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Adult Literature in 2006. The book was also nominated for a Hugo Award, but Gaiman asked for it to be withdrawn from the list of nominations, stating that he wanted to give other writers a chance, and it was really more fantasy than science fiction[19].

- Gaiman has won 19 Eisner Awards for his comics work.

- From the comics fans in the rec.arts.comics* newsgroups, Gaiman won the Squiddy Award for Best Writer five years in a row from 1990 to 1994. He was also named Best Writer of the 1990s in the Squiddy Awards for the decade.

- In 2007 he was awarded the Bob Clampett Humanitarian Award [20]

Neil Gaiman and Shakespeare

- Neil Gaiman draws on Shakespeare as a literary source. Allusions to Shakespeare's writings can be found in Anansi Boys, in which several lines of Hamlet appear, and the protagonist is compared to Macbeth more than once.

- In The Sandman series, Shakespeare himself appears in three stories. In these appearances he makes and fulfills a deal with Morpheus, who grants Shakespeare the gift of inspiration in exchange for two plays celebrating dreams: A Midsummer Night's Dream and The Tempest. (Sandman #13, "Men of Good Fortune"; "Midsummer Night's Dream"; and "The Tempest.")

- In Neverwhere the protagonist misquotes the line "Lead On, Macduff" from Macbeth, to which a character reacts: "Actually, it's 'Lay on, Macduff' but I didn't have the heart to correct him".

Bibliography

Neil Gaiman has written many comics and graphic novels, as well as numerous books (including 5 novels). He has also created a number of audio books, a TV miniseries, and the scripts for several movies.

See also

References

- ^ "Gaiman Interrupted: An Interview with Neil Gaiman (Part 2)" conducted by Lawrence Person, Nova Express, Volume 5, Number 4, Fall/Winter 2000, page 5.

- ^ McGinty, Stephen (February 25, 2006). "Dream weaver". The Scotsman.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "A writer's life: Neil Gaiman". The Telegraph. December 12, 2005.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Neil Gaiman - Biography". Biography. Retrieved 2006-06-21.

- ^ a b Lancaster, James (2005-10-11). "Everyone has the potential to be great". The Argus (Brighton). pp. 10–11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lancaster, James (2005-10-11). "Everyone has the potential to be great". The Argus (Brighton). pp. 10–11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) David Gaiman quote: "It's not me you should be interviewing. It's my son. Neil Gaiman. He's in the New York Times Bestsellers list. Fantasy. He's flavour of the month, very famous." - ^ a b "East Grinstead Hall of Fame - Neil Gaiman", East Grinstead Community Web Site.

- ^ "Neil Gaiman". Exclusive Books.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Science Fiction Weekly Interview

- ^ ref?

- ^ Sanchez, Robert (2006-08-02). "Neil Gaiman on Stardust and Death: High Cost of Living!". IESB.net. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (2007-01-09). "The best film of 2006 was..." Neil Gaiman's Journal. Neil Gaiman. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Tori Amos, "Tear in Your Hand," Little Earthquakes

- ^ "Gaiman Interrupted: An Interview with Neil Gaiman (Part 2)" conducted by Lawrence Person, Nova Express, Volume 5, Number 4, Fall/Winter 2000, page 2.

- ^ "There's a first time for everything", Neil Gaiman's journal, 28 September 2005

- ^ "Honor roll:Fiction books". Award Annals. 2007-08-14. Retrieved 2007-08-14.

- ^ "Hugo words..." Neil Gaiman's homepage. 2006-08-27. Retrieved 2007-04-17.

- ^ [3]

- Bender, Hy (1999), The Sandman Companion, New York: Vertigo DC Comics, ISBN 1563896443

External links

- Neil Gaiman's personal web site

- Official site for children's books with Dave McKean (US publisher)

- Official site for children's books with Dave McKean (UK publisher)

- Neil Gaiman at IMDb

- Neil Gaiman at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Neil Gaiman at the Internet Book List

- neilgaiman.info: The Neil Gaiman wiki

- Exhaustive Neil Gaiman Bibliography

- 1960 births

- 2000 AD creators

- British people of Polish descent

- Eisner Award winners

- English bloggers

- English comics writers

- English fantasy writers

- English horror writers

- English Jews

- English novelists

- English science fiction writers

- English screenwriters

- English short story writers

- Harvey Award winners

- Hugo Award winning authors

- Literary collaborators

- Living people

- Nebula Award winning authors

- Old Ardinians

- Old Whitgiftians

- People from Hampshire

- Worldcon Guests of Honor