Dots per inch: Difference between revisions

Rocketmagnet (talk | contribs) Added References section |

|||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

DPI can only refer to images which are real physical entities, for example images printed onto paper, or displayed on a monitor. A digitally stored image has no real dimensions, measured in inches or centimeters. Therefore it is meaningless to say that a digitally stored image has a resolution of 72 DPI. For example, an image in .JPG format may measure 1000x1000 pixels, and therefore have a resolution of 1 megapixel. If this image were printed onto paper at a size of 4x4 inches, then the printed image would have been printed at 250 DPI. If the image were also printed at a size of 10x10 inches, then that printed image would have been printed at 100 DPI. |

DPI can only refer to images which are real physical entities, for example images printed onto paper, or displayed on a monitor. A digitally stored image has no real dimensions, measured in inches or centimeters. Therefore it is meaningless to say that a digitally stored image has a resolution of 72 DPI. For example, an image in .JPG format may measure 1000x1000 pixels, and therefore have a resolution of 1 megapixel. If this image were printed onto paper at a size of 4x4 inches, then the printed image would have been printed at 250 DPI. If the image were also printed at a size of 10x10 inches, then that printed image would have been printed at 100 DPI. |

||

However, |

However, digital file formats record a DPI value, which is to be used when printing the image. This number lets the printer know the intended size of the image. This is called the DPI of the image file. |

||

== Proposed alternative measurements == |

== Proposed alternative measurements == |

||

Revision as of 16:47, 12 October 2007

Dots per inch (DPI) is a measure of printing resolution, in particular the number of individual dots of ink a printer or toner can produce within a linear one-inch (2.54 cm) space.

DPI measurement

Up to a point, printers with higher DPI produce clearer and more detailed output. A printer does not necessarily have a single DPI measurement; it is dependent on print mode, which is usually influenced by driver settings. The range of DPI supported by a printer is most dependent on the print head technology it uses. A dot matrix printer, for example, applies ink via tiny rods striking an ink ribbon, and has a relatively low resolution, typically in the range of 60 to 90 DPI. An inkjet printer sprays ink through tiny nozzles, and is typically capable of 360 DPI. A laser printer applies toner through a controlled electrostatic charge, and may be in the range of 600 to 1800 DPI.

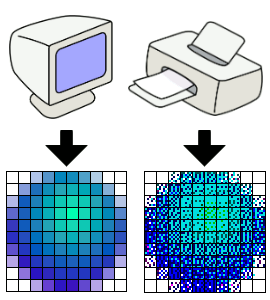

The DPI measurement of a printer often needs to be considerably higher than the pixels per inch (PPI) measurement of a video display in order to produce similar-quality output. This is due to the limited range of colours for each dot typically available on a printer. At each dot position, the simplest type of colour printer can print no dot, or a dot consisting of a fixed volume of ink in each of four colour channels (typically CMYK with cyan, magenta, yellow and black ink). Contrast this to a standard sRGB monitor where each pixel produces 256 intensities of light in each of three channels (RGB) to additively create 2563 = 16,777,216 colours. The number of unique colours for a printed CMYK dot from this simplest type of inkjet printer is only 8 since no coloured ink is visible when printed on black and black is used instead of CMY:

- white (no ink)

- cyan

- magenta

- yellow

- blue = cyan + magenta

- green = cyan + yellow

- red = magenta+yellow

- dark brown (not used) = cyan + magenta + yellow

- black

While some colour printers can produce variable drop volumes at each dot position, and may use additional ink colour channels, the number of colours is still typically less than on a monitor. Most printers must therefore produce additional colours through a halftone or dithering process. The exception to this rule is a Dye-sublimation printer that utilizes a printing method more akin to Pixels per inch.

The printing process could require a region from four to six dots (measured across each side) in order to faithfully reproduce the color contained in a single pixel. An image that is 100 pixels wide may need to be 400 to 600 dots in width in the printed output; if a 100×100-pixel image is to be printed inside a one-inch square, the printer must be capable of 400 to 600 dots per inch in order to accurately reproduce the image.

Misuses of DPI measurement

Owing in part to its conceptual similarity with other measurements of graphical resolution, the DPI measurement is frequently misused. For instance, it is common for an image scanner's sampling resolution to be specified in terms of DPI, though a more accurate measurement would be samples per inch. The number of pixels per inch in a computer display is sometimes specified in this way as well. Usage of the DPI measurement in these cases is inaccurate and misleading, though the intended meaning is usually clear based on context.

An example of misuse of the DPI scale would be if an LCD monitor manufacturer claimed that a 320x240 pixel 3" monitor (2.4"x1.8") actually had a resolution of ~533 DPI, (three times the resolution), because each pixel was made of three colored subpixels, (Red, Green and Blue). Technically they would be correct, but compared to the standard accepted practice of using whole pixels as a means to measure resolution a customer may be confused into thinking the relabelled monitor had a greater resolution and therefore better picture quality when in fact it would be exactly the same as normally labeled monitors. This misuse is generally found in advertising for in-car LCD displays.

A more common, far more severe misuse of the term DPI is when it is directly confused with some other measurement of resolution, often columns (horizontal resolution), as in referring to an XGA display as "1024 DPI".

Confusion between resolution and DPI

The word resolution is frequently used to refer to two different concepts:

- The total number of pixels in a digitally stored image. E.G. 5 megapixels.

- The number of pixels per linear inch when the image is printed. E.G. 72 DPI.

DPI can only refer to images which are real physical entities, for example images printed onto paper, or displayed on a monitor. A digitally stored image has no real dimensions, measured in inches or centimeters. Therefore it is meaningless to say that a digitally stored image has a resolution of 72 DPI. For example, an image in .JPG format may measure 1000x1000 pixels, and therefore have a resolution of 1 megapixel. If this image were printed onto paper at a size of 4x4 inches, then the printed image would have been printed at 250 DPI. If the image were also printed at a size of 10x10 inches, then that printed image would have been printed at 100 DPI.

However, digital file formats record a DPI value, which is to be used when printing the image. This number lets the printer know the intended size of the image. This is called the DPI of the image file.

Proposed alternative measurements

There are some ongoing efforts to abandon the DPI in favor of giving the inter-dot spacing in micrometers (µm).[citation needed] A resolution of 72 DPI for example equals an inter-dot spacing of about 350 µm, 96 DPI → 265 µm, 160 DPI 160 µm, 300 DPI → 85 µm, 4000 DPI → 6.4 µm. Going the other way, 1 µm → 25400 DPI, 30 µm → 850 DPI, 200 µm → 127 DPI. Note that 25400 = 1 DPI·µm, so dividing 25400 by a measurement in one of these units gives the measurement in the other unit.

Some have also proposed using “dots per centimeter” (DPCM). [1]

CRT Computer monitors are universally rated in dot pitch, which refers to the spacing between the sub-pixel red, green and blue dots which make up the pixels themselves.

See also

- Pixels per inch

- Samples per inch

- Lines per inch

- Metric typographic units

- Display resolution

- Mouse DPI

References

- ^ "Class ResolutionSyntax". Sun Microsystems. Retrieved 2007-10-12.