Innovation: Difference between revisions

rv per WP:EL#Links normally to be avoided items 14, 12, 4, and 5 |

Anita Burr (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 294: | Line 294: | ||

* [[Timeline of invention]] |

* [[Timeline of invention]] |

||

* [[Toolkits for User Innovation]] |

* [[Toolkits for User Innovation]] |

||

* [[Trends]] |

|||

* [[TRIZ]] |

* [[TRIZ]] |

||

* [[User innovation]] |

* [[User innovation]] |

||

Revision as of 23:36, 7 November 2007

The classic definitions of innovation include:

- the act of introducing something new: something newly introduced (The American Heritage Dictionary).

- the introduction of something new. (Merriam-Webster Online)

- a new idea, method or device. (Merriam-Webster Online)

- the successful exploitation of new ideas (Department of Trade and Industry, UK).

- change that creates a new dimension of performance Peter Drucker (Hesselbein, 2002)

- the process of making improvements by introducing something new [citation needed]

In economics, business and government policy,- something new - must be substantially different, not an insignificant change. In economics the change must increase value, customer value, or producer value. Innovations are intended to make someone better off, and the succession of many innovations grows the whole economy.

The term innovation may refer to both radical and incremental changes to products, processes or services. The often unspoken goal of innovation is to solve a problem. Innovation is an important topic in the study of economics, business, technology, sociology, and engineering. Since innovation is also considered a major driver of the economy, the factors that lead to innovation are also considered to be critical to policy makers.

Introduction

In the organisational context, innovation may be linked to performance and growth through improvements in efficiency, productivity, quality, competitive positioning, market share, etc. All organisations can innovate, including for example hospitals, universities, and local governments.

While innovation typically adds value, innovation may also have a negative or destructive effect as new developments clear away or change old organisational forms and practices. Organisations that do not innovate effectively may be destroyed by those that do. Hence innovation typically involves risk. A key challenge in innovation is maintaining a balance between process and product innovations where process innovations tend to involve a business model which may develop shareholder satisfaction through improved efficiencies while product innovations develop customer support however at the risk of costly R&D that can erode shareholder returns.

Conceptualizing innovation

Innovation has been studied in a variety of contexts, including in relation to technology, commerce, social systems, economic development, and policy construction. There are, therefore, naturally a wide range of approaches to conceptualising innovation in the scholarly literature. See, e.g., Fagerberg et al. (2004).

Fortunately, however, a consistent theme may be identified: innovation is typically understood as the introduction of something new and useful, for example introducing new methods, techniques, or practices or new or altered products and services.

Distinguishing from Invention and other concepts

"An important distinction is normally made between invention and innovation. Invention is the first occurrence of an idea for a new product or process, while innovation is the first attempt to carry it out into practice" (Fagerberg, 2004: 4)

It is useful, when conceptualizing innovation, to consider whether other words suffice. Recent authors point out that invention - the creation of new tools or the novel compilation of existing tools - is often confused with innovation. Many product and service enhancements may fall more rigorously under the term improvement. Change and creativity are also words that may often be substituted for innovation. What, then, is innovation that makes it necessary to have a different word from these others, or is it a catch-all word, a loose synonym? Much of the current business literature blurs the concept of innovation with value creation, value extraction and operational execution. In this view, an innovation is not an innovation until someone successfully implements and makes money on an idea. Extracting the essential concept of innovation from these other closely linked notions is no easy thing.

One emerging approach is to use these other notions as the constituent elements of innovation as an action: Innovation occurs when someone uses an invention - or uses existing tools in a new way - to change how the world works, how people organize themselves, and how they conduct their lives.

Note in this view inventions may be concepts, physical devices or any other set of things that facilitate an action. An innovation in this light occurs whether or not the act of innovating succeeds in generating value for its champions. Innovation is distinct from improvement in that it causes society to reorganize. It is distinct from problem solving and is perhaps more rigorously seen as new problem creation. And in this view, innovation applies whether the act generates positive or negative results.

Innovation in organizations

A convenient definition of innovation from an organizational perspective is given by Luecke and Katz (2003), who wrote:

- "Innovation . . . is generally understood as the introduction of a new thing or method . . . Innovation is the embodiment, combination, or synthesis of knowledge in original, relevant, valued new products, processes, or services. (p. 2)"

Don Sheelen also placed innovation at the pinnacle of modern business stating that:

- "Innovation is the lifeblood of any organization." Sheelan emphasizes that "without it, not only is their no growth, but, inevitably, a slow death."

Innovation typically involves creativity, but is not identical to it: innovation involves acting on the creative ideas to make some specific and tangible difference in the domain in which the innovation occurs. For example, Amabile et al (1996) propose:

- "All innovation begins with creative ideas . . . We define innovation as the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization. In this view, creativity by individuals and teams is a starting point for innovation; the first is necessary but not sufficient condition for the second". (p. 1154-1155).

For innovation to occur, something more than the generation of a creative idea or insight is required: the insight must be put into action to make a genuine difference, resulting for example in new or altered business processes within the organisation, or changes in the products and services provided.

A further characterization of innovation is as an organizational or management process. For example, Davila et al (2006), write:

- "Innovation, like many business functions, is a management process that requires specific tools, rules, and discipline." (p. xvii)

From this point of view the emphasis is moved from the introduction of specific novel and useful ideas to the general organizational processes and procedures for generating, considering, and acting on such insights leading to significant organizational improvements in terms of improved or new business products, services, or internal processes.

Through these varieties of viewpoints, creativity is typically seen as the basis for innovation, and innovation as the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization (c.f. Amabile et al 1996 p.1155). From this point of view, creativity may be displayed by individuals, but innovation occurs in the organizational context only.

It should be noted, however, that the term 'innovation' is used by many authors rather interchangeably with the term 'creativity' when discussing individual and organizational creative activity. As Davila et al (2006) comment,

- "Often, in common parlance, the words creativity and innovation are used interchangeably. They shouldn't be, because while creativity implies coming up with ideas, it's the "bringing ideas to life" . . . that makes innovation the distinct undertaking it is."

The distinctions between creativity and innovation discussed above are by no means fixed or universal in the innovation literature. They are however observed by a considerable number of scholars in innovation studies.

Technological concepts of innovation

The OECD defines Technological Innovation in the Oslo Manual (1995) as:

- Technological product and process (TPP) innovations comprise implemented technologically new products and processes and significant technological improvements in products and processes. A TPP innovation has been implemented if it has been introduced on the market (product innovation) or used within a production process (process innovation). TPP innovations involve a series of scientific, technological, organisational, financial and commercial activities. The TPP innovating firm is one that has implemented technologically new or significantly technologically improved products or processes during the period under review.

A 2005/6 MIT survey of innovation in technology found a number of characteristics common to innovators working in that field.

- they are not troubled by the idea of failure,

- they realise that failure can be learned from and that the 'failed' technology can later be re-used for other purposes,

- they know innovation requires that one works in advanced areas where failure is a real possibility,

- innovators are curious about what is happening in a myriad of disciplines, not only their own specialism,

- innovators are open to third-party experiments with their products,

- they recognize that a useful innovation must be "robust", flexible and adaptable,

- innovators delight in spotting a need that we don't even know we harbor, and then fulfilling that need with a new innovation, and as such

- innovators like to make products that are immediately useful to their first users.

Economic conceptions of innovation

Joseph Schumpeter defined economic innovation in 1934:

- The introduction of a new good —that is one with which consumers are not yet familiar—or of a new quality of a good.

- The introduction of a new method of production, which need by no means be founded upon a discovery scientifically new, and can also exist in a new way of handling a commodity commercially.

- The opening of a new market, that is a market into which the particular branch of manufacture of the country in question has not previously entered, whether or not this market has existed before.

- The conquest of a new source of supply of raw materials or half-manufactured goods, again irrespective of whether this source already exists or whether it has first to be created.

- The carrying out of the new organization of any industry, like the creation of a monopoly position (for example through trustification) or the breaking up of a monopoly position

Schumpeter's focus on innovation is reflected in Neo-Schumpeterian economics.

Innovation is also studied by economists in a variety of contexts, for example in theories of entrepreneurship or in Paul Romer's New Growth Theory.

Transaction cost and network theory perspectives

According to Regis Cabral (1998, 2003):

- "Innovation is a new element introduced in the network which changes, even if momentarily, the costs of transactions between at least two actors, elements or nodes, in the network."

Types of innovation

Scholars have identified at a variety of classifications for types innovations. Here is an unordered ad-hoc list of examples:

- Business model innovation

- involves changing the way business is done in terms of capturing value .

- Marketing innovation

- is the development of new marketing methods with improvement in product design or packaging, product promotion or pricing.

- Organizational innovation

- involves the creation or alteration of business structures, practices, and models, and may therefore include process, marketing and business model innovation.

- Process innovation

- involves the implementation of a new or significantly improved production or delivery method.

- Product innovation

- involves the introduction of a new good or service that is new or substantially improved. This might include improvements in functional characteristics, technical abilities, ease of use, or any other dimension.

- Service innovation

- refers to service product innovation which might be, compared to goods product innovation or process innovation, relatively less involving technological advance but more interactive and information-intensive .

- Supply chain innovation

- where innovations occur in the sourcing of input products from suppliers and the delivery of output products to customers

- Substantial innovation

- introduces a different product or service within the same line, such as the movement of a candle company into marketing the electric lightbulb.

- Financial innovation

- through which new financial services and products are developed, by combining basic financial attributes (ownership, risk-sharing, liquidity, credit) in progressive innovative ways, as well as reactive exploration of borders and strength of tax law. Through a cycle of development, directive compliance is being sharpened on opportunities, so new financial services and products are continuously shaped and progressed to be adopted. The dynamic spectrum of financial innovation, where business processes, services and products are adapted and improved so new valuable chains emerge, therefore may be seen to involve most of the above mentioned types of innovation.

- Incremental innovations

- is a step forward along a technology trajectory, or from the known to the unknown, with little uncertainty about outcomes and success and is generally minor improvements made by those working day to day with existing methods and technology (both process and product), responding to short term goals. Most innovations are incremental innovations. A value-added business process, this involves making minor changes over time to sustain the growth of a company without making sweeping changes to product lines, services, or markets in which competition currently exists.

- Breakthrough, disruptive or radical innovation

- involves launching an entirely novel product or service rather than providing improved products & services along the same lines as currently. The uncertainty of breakthrough innovations means that seldom do companies achieve their breakthrough goals this way, but those times that breakthrough innovation does work, the rewards can be tremendous. Involves larger leaps of understanding, perhaps demanding a new way of seeing the whole problem, probably taking a much larger risk than many people involved are happy about. There is often considerable uncertainty about future outcomes. There may be considerable opposition to the proposal and questions about the ethics, practicality or cost of the proposal may be raised. People may question if this is, or is not, an advancement of a technology or process. Radical innovation involves considerable change in basic technologies and methods, created by those working outside mainstream industry and outside existing paradigms. Sometimes it is very hard to draw a line between both.

- New technological systems (systemic innovations)

- that may give rise to new industrial sectors, and induce major change across several branches of the economy.

- Social innovation

- a number of different definitions, but predominantly refers to either innovations that aim to meet a societal need or the social processes used to develop an innovation

Innovation and market outcome

Market outcome from innovation can be studied from different lenses. The industrial organizational approach of market characterization according to the degree of competitive pressure and the consequent modelling of firm behaviour often using sophisticated game theoretic tools, while permitting mathematical modelling, has shifted the ground away from an intuitive understanding of markets. The earlier visual framework in economics, of market demand and supply along price and quantity dimensions, has given way to powerful mathematical models which though intellectually satisfying has led policy makers and managers groping for more intuitive and less theoretical analyses to which they can relate to at a practical level. Non quantifiable variables find little place in these models, and when they do, mathematical gymnastics (such as the use of different demand elasticities for differentiated products) embrace many of these qualitative variables, but in an intuitively unsatisfactory way.

In the management (strategy) literature on the other hand, there is a vast array of relatively simple and intuitive models for both managers and consultants to choose from. Most of these models provide insights to the manager which help in crafting a strategic plan consistent with the desired aims. Indeed most strategy models are generally simple, wherein lie their virtue. In the process however, these models often fail to offer insights into situations beyond that for which they are designed, often due to the adoption of frameworks seldom analytical, seldom rigorous. The situational analyses of these models often tend to be descriptive and seldom robust and rarely present behavioural relationship between variables under study.

From an academic point of view, there is often a divorce between industrial organisation theory and strategic management models. While many economists view management models as being too simplistic, strategic management consultants perceive academic economists as being too theoretical, and the analytical tools that they devise as too complex for managers to understand.

Innovation literature while rich in typologies and descriptions of innovation dynamics is mostly technology focused. Most research on innovation has been devoted to the process (technological) of innovation, or has otherwise taken a how to (innovate) approach. The integrated innovation model of Soumodip Sarkar goes some way to providing the academic, the manager and the consultant an intuitive understanding of the innovation – market linkages in a simple yet rigorous framework in his book , Innovation, Market Archetypes and Outcome- An Integrated Framework.[1]

The integrated model presents a new framework for understanding firm and market dynamics, as it relates to innovation. The model is enriched by the different strands of literature - industrial organization, management and innovation. The integrated approach that allows the academic, the management consultant and the manager alike to understand where a product (or a single product firm) is located in an integrated innovation space, why it is so located and which then provides valuable clues as to what to do while designing strategy. The integration of the important determinant variables in one visual framework with a robust and an internally consistent theoretical basis is an important step towards devising comprehensive firm strategy. The integrated framework provides vital clues towards framing a what to guide for managers and consultants. Furthermore, the model permits metrics and consequently diagnostics of both the firm and the sector and this set of assessment tools provide a valuable guide for devising strategy.

Sources of innovation

There are several sources of innovation. In the linear model the traditionally recognized source is manufacturer innovation. This is where an agent (person or business) innovates in order to sell the innovation. Another source of innovation, only now becoming widely recognized, is end-user innovation. This is where an agent (person or company) develops an innovation for their own (personal or in-house) use because existing products do not meet their needs. Eric von Hippel has identified end-user innovation as, by far, the most important and critical in his classic book on the subject, Sources of Innovation.[2]

Innovation by businesses is achieved in many ways, with much attention now given to formal research and development for "breakthrough innovations." But innovations may be developed by less formal on-the-job modifications of practice, through exchange and combination of professional experience and by many other routes. The more radical and revolutionary innovations tend to emerge from R&D, while more incremental innovations may emerge from practice - but there are many exceptions to each of these trends.

Regarding user innovation, rarely user innovators may become entrepreneurs, selling their product, or more often they may choose to trade their innovation in exchange for other innovations. Nowadays, they may also choose to freely reveal their innovations, using methods like open source. In such networks of innovation the creativity of the users or communities of users can further develop technologies and their use.

Whether innovation is mainly supply-pushed (based on new technological possibilities) or demand-led (based on social needs and market requirements) has been a hotly debated topic. Similarly, what exactly drives innovation in organizations and economies remains an open question.

More recent theoretical work moves beyond this simple dualistic problem, and through empirical work shows that innovation does not just happen within the industrial supply-side, or as a result of the articulation of user demand, but though a complex processes that links many different players together - not only developers and users, but a wide variety of intermediary organistions such as consultancies, standards bodies etc. Work on social networks suggests that much of the most successful innovation occures at the boundaries of organisations and industries where the problems and needs of users, and the potential of technologies can be linked together in a creative process that challenges both.

Value of experimentation in innovation

When an innovative idea requires a new business model, or radically redesigns the delivery of value to focus on the customer, a real world experimentation approach increases the chances of market success. New business models and customer experiences can’t be tested through traditional market research methods. Pilot programs for new innovations set the path in stone too early thus increasing the costs of failure.

Stefan Thomke of Harvard Business School has written a definitive book on the importance of experimentation. Experimentation Matters argues that every company’s ability to innovate depends on a series of experiments [successful or not], that help create new products and services or improve old ones. That period between the earliest point in the design cycle and the final release should be filled with experimentation, failure, analysis, and yet another round of experimentation. “Lather, rinse, repeat,” Thomke says. Unfortunately, uncertainty often causes the most able innovators to bypass the experimental stage.

In his book, Thomke outlines six principles companies can follow to unlock their innovative potential.

- Anticipate and Exploit Early Information Through ‘Front-Loaded’ Innovation Processes

- Experiment Frequently but Do Not Overload Your Organization.

- Integrate New and Traditional Technologies to Unlock Performance.

- Organize for Rapid Experimentation.

- Fail Early and Often but Avoid ‘Mistakes’.

- Manage Projects as Experiments.[3]

Thomke further explores what would happen if the principles outlined above were used beyond the confines of the individual organization. For instance, in the state of Rhode Island, innovators are collaboratively leveraging the state's compact geography, economic and demographic diversity and close-knit networks to quickly and cost-effectively test new business models through a real-world experimentation lab. [citation needed]

Diffusion of innovations

Once innovation occurs, innovations may be spread from the innovator to other individuals and groups. This process has been studied extensively in the scholarly literature from a variety of viewpoints, most notably in Everett Rogers' classic book, The Diffusion of Innovations. However, this 'linear model' of innovation has been substantinally challenged by scholars in the last 20 years, and much research has shown that the simple invention-innovation-diffusion model does not do justice to the multilevel, non-linear processes that firms, entrepreneurs and users participate in to create successful and sustainable innovations.

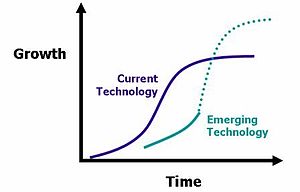

Rogers proposed that the life cycle of innovations can be described using the ‘s-curve’ or diffusion curve. The s-curve maps growth of revenue or productivity against time. In the early stage of a particular innovation, growth is relatively slow as the new product establishes itself. At some point customers begin to demand and the product growth increases more rapidly. New incremental innovations or changes to the product allow growth to continue. Towards the end of its life cycle growth slows and may even begin to decline. In the later stages, no amount of new investment in that product will yield a normal rate of return.

The s-curve is derived from half of a normal distribution curve. There is an assumption that new products are likely to have "product Life". i.e. a start-up phase, a rapid increase in revenue and eventual decline. In fact the great majority of innovations never get off the bottom of the curve, and never produce normal returns.

Innovative companies will typically be working on new innovations that will eventually replace older ones. Successive s-curves will come along to replace older ones and continue to drive growth upwards. In the figure above the first curve shows a current technology. The second shows an emerging technology that current yields lower growth but will eventually overtake current technology and lead to even greater levels of growth. The length of life will depend on many factors.

Goals of innovation

Programs of organizational innovation are typically tightly linked to organizational goals and objectives, to the business plan, and to market competitive positioning.

For example, one driver for innovation programs in corporations is to achieve growth objectives. As Davila et al (2006) note,

- "Companies cannot grow through cost reduction and reengineering alone . . . Innovation is the key element in providing aggressive top-line growth, and for increasing bottom-line results" (p.6)

It is not surprising, therefore, that companies such as General Electric and Procter & Gamble have embraced the management of innovation enthusiastically, with the primary goal of driving growth and, consequently, improving shareholder value.

In general, business organisations spend a significant amount of their turnover on innovation i.e. making changes to their established products, processes and services. The amount of investment can vary from as low as a half a percent of turnover for organisations with a low rate of change to anything over twenty percent of turnover for organisations with a high rate of change.

The average investment across all types of organizations is four percent. For an organisation with a turnover of say one billion currency units, this represents an investment of forty million units. This budget will typically be spread across various functions including marketing, product design, information systems, manufacturing systems and quality assurance.

The investment may vary by industry and by market positioning.

One survey across a large number of manufacturing and services organisations found, ranked in decreasing order of popularity, that systematic programs of organizational innovation are most frequently driven by:

- Improved quality

- Creation of new markets

- Extension of the product range

- Reduced labour costs

- Improved production processes

- Reduced materials

- Reduced environmental damage

- Replacement of products/services

- Reduced energy consumption

- Conformance to regulations

These goals vary between improvements to products, processes and services and dispel a popular myth that innovation deals mainly with new product development. Most of the goals could apply to any organisation be it a manufacturing facility, marketing firm, hospital or local government.

Failure of innovation

Attaining goals must be the ultimate objective of the innovation process. Unfortunately, most innovation fails to meet organisational goals.

Figures vary considerably depending on the research. Some research quotes failure rates of fifty percent while other research quotes as high as ninety percent of innovation has no impact on organisational goals. One survey regarding product innovation quotes that out of three thousand ideas for new products, only one becomes a success in the marketplace. [citation needed] Failure is an inevitable part of the innovation process, and most successful organisations factor in an appropriate level of risk. Perhaps it is because all organisations experience failure that many choose not to monitor the level of failure very closely. The impact of failure goes beyond the simple loss of investment. Failure can also lead to loss of morale among employees, an increase in cynicism and even higher resistance to change in the future.

Innovations that fail are often potentially ‘good’ ideas but have been rejected or ‘shelved’ due to budgetary constraints, lack of skills or poor fit with current goals. Failures should be identified and screened out as early in the process as possible. Early screening avoids unsuitable ideas devouring scarce resources that are needed to progress more beneficial ones. Organizations can learn how to avoid failure when it is openly discussed and debated. The lessons learned from failure often reside longer in the organisational consciousness than lessons learned from success. While learning is important, high failure rates throughout the innovation process are wasteful and a threat to the organisation's future.

The causes of failure have been widely researched and can vary considerably. Some causes will be external to the organisation and outside its influence of control. Others will be internal and ultimately within the control of the organisation. Internal causes of failure can be divided into causes associated with the cultural infrastructure and causes associated with the innovation process itself. Failure in the cultural infrastructure varies between organisations but the following are common across all organisations at some stage in their life cycle (O'Sullivan, 2002):

- Poor Leadership

- Poor Organisation

- Poor Communication

- Poor Empowerment

- Poor Knowledge Management

Common causes of failure within the innovation process in most organisations can be distilled into five types:

- Poor goal definition

- Poor alignment of actions to goals

- Poor participation in teams

- Poor monitoring of results

- Poor communication and access to information

Effective goal definition requires that organisations state explicitly what their goals are in terms understandable to everyone involved in the innovation process. This often involves stating goals in a number of ways. Effective alignment of actions to goals should link explicit actions such as ideas and projects to specific goals. It also implies effective management of action portfolios. Participation in teams refers to the behaviour of individuals in and of teams, and each individual should have an explicitly allocated responsibility regarding their role in goals and actions and the payment and rewards systems that link them to goal attainment. Finally, effective monitoring of results requires the monitoring of all goals, actions and teams involved in the innovation process.

Innovation can fail if seen as an organisational process whose success stems from a mechanistic approach i.e. 'pull lever obtain result'. While 'driving' change has an emphasis on control, enforcement and structure it is only a partial truth in achieving innovation. Organisational gatekeepers frame the organisational environment that "Enables" innovation; however innovation is "Enacted" - recognised, developed, applied and adopted - through individuals.

Individuals are the 'atom' of the organisation close to the minutiae of daily activities. Within individuals gritty appreciation of the small detail combines with a sense of desired organisational objectives to deliver (and innovate for) a product/service offer.

From this perspective innovation succeeds from strategic structures that engage the individual to the organisation's benefit. Innovation pivots on intrinsically motivated individuals, within a supportive culture, informed by a broad sense of the future.

Innovation, implies change, and can be counter to an organisation's orthodoxy. Space for fair hearing of innovative ideas is required to balance the potential autoimmune exclusion that quells an infant innovative culture.

Measures of innovation

Individual and team-level assessment can be conducted by surveys and workshops. Business measures related to finances, processes, employees and customers in balanced scorecards can be viewed from the innovation perspective (e.g. new product revenue, time to market, customer and employee perception & satisfaction). Organizational capabilities can be evaluated through various evaluation frameworks e.g. efqm (European foundation for quality management) -model.

The OECD Oslo Manual from 1995 suggests standard guidelines on measuring technological product and process innovation. Some people consider the Oslo Manual complementary to the Frascati Manual from 1963. The new Oslo manual from 2005 takes a wider perspective to innovation, and includes marketing and organizational innovation. Other ways of measuring innovation have traditionally been expenditure, for example, investment in R&D (Research and Development) as percentage of GNP (Gross National Product). Whether this is a good measurement of Innovation has been widely discussed and the Oslo Manual has incorporated some of the critique against earlier methods of measuring. This being said, the traditional methods of measuring still inform many policy decisions. The EU Lisbon Strategy has set as a goal that their average expenditure on R&D should be 3 % of GNP.

The Oslo Manual is focused on North America, Europe, and other rich economies. In 2001 for Latin America and the Caribbean countries it was created the Bogota Manual

Many scholars claim that there is a great bias towards the "science and technology mode" (S&T-mode or STI-mode), while the "learning by doing, using and interacting mode" (DUI-mode) is widely ignored. For an example, that means you can have the better high tech or software, but there are also crucial learning tasks important for innovation. But these measurements and research are rarely done.

Public awareness

Public awareness of innovation is an important part of the innovation process. This is further discussed in the emerging fields of innovation journalism and innovation communication.

See also

- Creative destruction

- Creative problem solving

- Diffusion (anthropology)

- Edward de Bono

- Emerging technologies

- Hype cycle

- Idea Management

- Individual capital

- Induced innovation

- Ingenuity

- Invention

- Open Innovation

- Patent

- Public domain

- Research

- The International Society for Professional Innovation Management

- Timeline of invention

- Toolkits for User Innovation

- Trends

- TRIZ

- User innovation

- Value network

- Six Thinking Hats

- Lateral Thinking

References

- ^ Sarkar, Soumodip (2007). Innovation, Market Archetypes and Outcome- An Integrated Framework. Springer Verlag. ISBN 379081945X.

- ^ von Hippel, Eric (1988). The Sources of Innovation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509422-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - ^ Thomke, Stefan H. (2003) Experimentation Matters: Unlocking the Potential of New Technologies for Innovation. Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1578517508. [1]

- Amabile, Teresa (1996). Creativity in Context. New York: Westview Press.

- Amabile, Teresa (1996). "Assessing the work environment for creativity". Academy of Management Journal. 39 (5): 1154–1184.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Barras, R. (1984). "Towards a theory of innovation in services". Research Policy. 15: 161–73.

- Cabral, Regis (2003). "Development, Science and". In Heilbron, J. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to The History of Modern Science. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 205–207.

{{cite book}}: External link in|title= - Cabral, Regis (1998). "Refining the Cabral-Dahab Science Park Management Paradigm". Int. J. Technology Management. 16 (8): 813–818. doi:10.1504/IJTM.1998.002694..

- Chakravorti, Bhaskar (2003). The Slow Pace of Fast Change: Bringing Innovations to Market in a Connected World. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chesbrough, Henry William (2003). Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1-57851-837-7.

- Christensen, Clayton M. (1997). The Innovator's Dilemma. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 0-06-052199-6.

- Davila, Tony (2006). Making Innovation Work: How to Manage It, Measure It, and Profit from It. Upper Saddle River: Wharton School Publishing. ISBN 0-13-149786-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dosi, Giovanni (1982). "Technological paradigms and technological trajectories". Research Policy. 11 (3)..

- Ettlie, John (2006). Managing Innovation, Second Edition. Butterworth-Heineman, an imprint of Elsevier. ISBN 0-7506-7895-X.

- Evangelista, Rinaldo (2000). "Sectoral patterns of technological change in services, economics of innovation". Economics of Innovation and New Technology. 9: 183–221.

- Fagerberg, Jan (2004). "Innovation: A Guide to the Literature". In Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–26. ISBN 0-19-926455-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Freeman, Chris (1984). "Prometheus Unbound". Futures. 16 (5): 494-507.

- Hesselbein, Frances, Marshall Goldsmith, and Iain Sommerville, ed. (2002). Leading for Innovation: And organizing for results. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-7879-5359-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Hitcher, Waldo (2006). Innovation Paradigm Replaced. Wiley.

- Luecke, Richard (2003). Managing Creativity and Innovation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1-59139-112-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Mansfield, Edwin (1985). "How Rapidly Does New Industrial Technology Leak Out?". Journal of Industrial Economics. 34 (2): 217–223.

- Miles, Ian (2000). "Services Innovation: Coming of Age in the Knowledge Based Economy". International Journal of Innovation Management. 14 (4): 371-389.

- Miles, Ian (2004). "Innovation in Services". In Fagerberg, Jan, David C. Mowery and Richard R. Nelson (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Innovations. Oxford University Press. pp. 433–458. ISBN 0-19-926455-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Nelson, Richard (1977). "In search of a useful theory of Innovation". Research Policy. 6 (1): 36–76.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

- Nordfors, David (2004). "The Role of Journalism in Innovation Systems" (pdf). Innovation Journalism. 1 (7). ISSN 1549-9049.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - OECD The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities. Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Oslo Manual. 2nd edition, DSTI, OECD / European Commission Eurostat, Paris 31 Dec 1995.

- O'Sullivan, David (2002). "Framework for Managing Development in the Networked Organisations". Journal of Computers in Industry. 47 (1). Elsevier Science Publishers B. V.: 77–88. ISSN 0166-3615.

- Rogers, Everett M. (1962). Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Rosenburgh, Nathan (1975). Perspectives on Technology. Cambridge, London and N.Y.: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Schumpeter, Joseph (1934). The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Sapprasert, Koson (2007). "The impact of ICT on the growth of the service industries". TIK working papers on Innovation Studies. 20070531.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); External link in|journal=and|title= - Scotchmer, Suzanne (2004). Innovation and Incentives. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Silverstein, David (2005). INsourcing Innovation: How to Transform Business as Usual into Business as Exceptional. Longmont, CO: Breakthrough Performance Press. ISBN 0-9769010-0-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sloane, Paul (2003). The Leader's Guide to Lateral Thinking Skills. Kogan Page.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Stein, Morris (1974). Stimulating creativity. New York: Academic Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Utterback, James M. (1993). "Innovation, Competition, and Industry Structure". Research Policy. 22 (1): 1–21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - von Hippel, Eric (2005). Democratizing Innovation. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-22074-1.

- Woodman, Richard .W. (1993). "Toward a theory of organizational creativity". Academy of Management Review. 18 (2): 293–321.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wolpert, John (2002). "Breaking Out of the Innovation Box". Harvard Business Review. August.

Innovation Links

- SPRU Science and Technology Policy Research - Origin of the concept of 'Systems of Innovation' and centre of research and learning on innovation policy and innovation management.

- Innovation Studies at Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture (TIK), University of Oslo - One of the world's leading research centres on Innovation Studies.

- TIK working papers on Innovation studies at RePec.

- Research effort in Understanding Innovation (Centre for Advanced Study).

- PREST: now part of Manchester Institute of Innovation Research, centre for research, consultancy and teaching on innovation (especially in services), innovation policy, and related topics such as research evaluation and Technlogy Foresight.

- Welcome to the DTI's Innovation Home Page - Department of Trade and Industry, UK.

- Innovation and Technology Policy - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- Welcome to The Innovation Unit's homepage - The Innovation Unit - one of the UK's leading organisations for promoting innovation to improve education.

- Academic article on Being a Systems Innovator on SSRN

- European Union: