Blackface: Difference between revisions

m →Blackface minstrelsy and world popular culture: removed extra bracket character |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

[[Image:BlackfaceMinstrelsPostcard.jpg|thumb|left|250px|This postcard, published circa 1908, shows a white minstrel team. While both are wearing wigs, the man on the left is in blackface and [[drag (clothing)|drag]].]]Rice traveled the [[United States|U.S.]], performing under the [[pseudonym]] "Daddy Jim Crow". The name later became attached to [[Jim Crow law|statutes]] that further codified the reinstitution of [[Racial segregation|segregation]] and [[racial discrimination|discrimination]] after [[Reconstruction]]. |

[[Image:BlackfaceMinstrelsPostcard.jpg|thumb|left|250px|This postcard, published circa 1908, shows a white minstrel team. While both are wearing wigs, the man on the left is in blackface and [[drag (clothing)|drag]].]]Rice traveled the [[United States|U.S.]], performing under the [[pseudonym]] "Daddy Jim Crow". The name later became attached to [[Jim Crow law|statutes]] that further codified the reinstitution of [[Racial segregation|segregation]] and [[racial discrimination|discrimination]] after [[Reconstruction]]. |

||

Initially, blackface performers were part of traveling troupes who performed in [[minstrel show]]s. In addition to music and dance, minstrel shows featured comical skits in which performers portrayed buffoonish, lazy, superstitious black characters who were cowardly and lascivious, who stole, lied pathologically, and mangled the English language. Such troupes in the early days of minstrelsy were all male, so cross-dressing white men also played black women who often were either unappealingly and grotesquely mannish; in the matronly, [[mammy archetype|mammy]] mold; or highly sexually provocative. At the time, the stage also featured comic [[stereotype]]s of conniving, venal [[Jew]]s; cheap [[Scottish people|Scotsmen]]; drunken [[Ireland|Irishmen]]; ignorant white [[Southern United States|southerners]]; gullible rural folk and the like. |

Initially, blackface performers were part of traveling troupes who performed in [[minstrel show]]s. In addition to music and dance, minstrel shows featured comical skits in which performers portrayed buffoonish, lazy, superstitious black characters who were cowardly and lascivious, who stole, lied pathologically, and mangled the English language. Such troupes in the early days of minstrelsy were all male, so cross-dressing white men also played black women who often were either unappealingly and grotesquely mannish; in the matronly, [[mammy archetype|mammy]] mold; or highly sexually provocative. At the time, the stage also featured comic people who love sex [[stereotype]]s of conniving, venal [[Jew]]s; cheap [[Scottish people|Scotsmen]]; drunken [[Ireland|Irishmen]]; ignorant white [[Southern United States|southerners]]; gullible rural folk and the like. |

||

Minstrel shows were a very popular show business phenomenon in the U.S. from 1828 through the 1930s, also enjoying some popularity in the [[United Kingdom|UK]] and in other parts of [[Europe]] in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, the genre played an important role in shaping perceptions of and prejudices about blacks generally and [[African Americans]] in particular. Some social commentators have stated that blackface provided an outlet for whites' fear of the unknown and the unfamiliar, and a socially acceptable way of expressing their feelings and fears about race and control. Writes Eric Lott in ''Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class'', "The black mask offered a way to play with the collective fears of a degraded and threatening—and male—Other while at the same time maintaining some symbolic control over them." (Lott, 25) |

Minstrel shows were a very popular show business phenomenon in the U.S. from 1828 through the 1930s, also enjoying some popularity in the [[United Kingdom|UK]] and in other parts of [[Europe]] in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, the genre played an important role in shaping perceptions of and prejudices about blacks generally and [[African Americans]] in particular. Some social commentators have stated that blackface provided an outlet for whites' fear of the unknown and the unfamiliar, and a socially acceptable way of expressing their feelings and fears about race and control. Writes Eric Lott in ''Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class'', "The black mask offered a way to play with the collective fears of a degraded and threatening—and male—Other while at the same time maintaining some symbolic control over them." (Lott, 25) |

||

Revision as of 22:04, 20 November 2007

Blackface is a style of theatrical makeup that originated in the United States, used to affect the countenance of an iconic, racist American archetype—that of the darky or coon. Blackface also refers to a genre of musical and comedic theatrical presentation in which blackface makeup is worn. White blackface performers in the past used burnt cork and later greasepaint or shoe polish to blacken their skin and exaggerate their lips, often wearing woolly wigs, gloves, tailcoats, or ragged clothes to complete the transformation. Later, black artists also performed in blackface.

Blackface was an important performance tradition in the American theater for over 100 years and was also popular overseas. Stereotypes embodied in the stock characters of blackface minstrelsy played a significant role in cementing and proliferating racist images, attitudes and perceptions worldwide. In some quarters, the caricatures that were the legacy of blackface persist to the present day and are a cause of ongoing controversy.

By the mid-20th century, changing attitudes about race and racism effectively ended the prominence of blackface performance in the U.S. and elsewhere. However, it remains in relatively limited use as a theatrical device, mostly outside the U.S., and is more commonly used today as edgy social commentary or satire. Perhaps the most enduring effect of blackface is the precedent it established in the introduction of African American culture to an international audience, albeit through a distorted lens. Blackface minstrelsy's groundbreaking appropriation[1], exploitation, and assimilation of African-American culture—as well as the inter-ethnic artistic collaborations that stemmed from it—were but a prologue to the lucrative packaging, marketing, and dissemination of African-American cultural expression and its myriad derivative forms in today's world popular culture.[2][3]

History and the shaping of racist archetypes

Lewis Hallam, Jr., a white comedic actor, brought blackface to prominence as a theatrical device when playing the role of an inebriated black man onstage in 1789. The play attracted notice, and other performers adopted the style. White comedian Thomas D. Rice later popularized blackface, introducing the song "Jump Jim Crow" accompanied by a dance in his stage act in 1828. The song had a syncopated rhythm and purportedly recreated the dancing of a crippled black stable hand, Jim Cuff, or "Jim Crow", whom Rice had seen in Cincinnati, Ohio:

- First on de heel tap,

- Den on the toe

- Every time I wheel about

- I jump Jim Crow.

- Wheel about and turn about

- An' do j's so.

- And every time I wheel about,

- I jump Jim Crow.

- — 1823 sheet music

Rice traveled the U.S., performing under the pseudonym "Daddy Jim Crow". The name later became attached to statutes that further codified the reinstitution of segregation and discrimination after Reconstruction.

Initially, blackface performers were part of traveling troupes who performed in minstrel shows. In addition to music and dance, minstrel shows featured comical skits in which performers portrayed buffoonish, lazy, superstitious black characters who were cowardly and lascivious, who stole, lied pathologically, and mangled the English language. Such troupes in the early days of minstrelsy were all male, so cross-dressing white men also played black women who often were either unappealingly and grotesquely mannish; in the matronly, mammy mold; or highly sexually provocative. At the time, the stage also featured comic people who love sex stereotypes of conniving, venal Jews; cheap Scotsmen; drunken Irishmen; ignorant white southerners; gullible rural folk and the like.

Minstrel shows were a very popular show business phenomenon in the U.S. from 1828 through the 1930s, also enjoying some popularity in the UK and in other parts of Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, the genre played an important role in shaping perceptions of and prejudices about blacks generally and African Americans in particular. Some social commentators have stated that blackface provided an outlet for whites' fear of the unknown and the unfamiliar, and a socially acceptable way of expressing their feelings and fears about race and control. Writes Eric Lott in Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, "The black mask offered a way to play with the collective fears of a degraded and threatening—and male—Other while at the same time maintaining some symbolic control over them." (Lott, 25)

White minstrel shows featured white performers pretending to be blacks, playing their versions of black music and speaking ersatz black dialects. American humorist and author Mark Twain reminisced near the end of his life about the shows he had seen in his youth:

the real nigger-show—the genuine nigger-show, the extravagant nigger-show—the show which to me had no peer and whose peer has not yet arrived, in my experience.... if I could have the nigger-show back again, in its pristine purity and perfection, I should have but little further use for opera. It seems to me that to the elevated mind and the sensitive spirit the hand-organ and the nigger-show are a standard and a summit to whose rarefied altitude the other forms of musical art may not hope to reach.[4]

The songs of northern composer Stephen Foster figured prominently in blackface minstrel shows of the period. Though written in dialect and certainly politically incorrect by today's standards, his later songs were free of the ridicule and blatantly racist caricatures that typified other songs of the genre. Foster's works treated slaves and the South in general with an often cloying sentimentality that appealed to audiences of the day.

By 1840, African-American performers also were performing in blackface makeup. Frederick Douglass wrote in 1849 about one such troupe, Gavitt's Original Ethiopian Serenaders: "It is something to be gained when the colored man in any form can appear before a white audience." Nonetheless, Douglass generally abhorred blackface and was one of the first people to write against the institution of blackface minstrelsy, condemning it as racist in nature, with inauthentic, northern, white origins.

When all-black minstrel shows began to proliferate in the 1860s, however, they in turn often were billed as "authentic" and "the real thing". Despite often smaller budgets and smaller venues, their public appeal sometimes rivalled that of white minstrel troupes. In the execution of authentic black music and the percussive, polyrhythmic tradition of "pattin' Juba", when the only instruments performers used were their hands and feet, clapping and slapping their bodies and shuffling and stomping their feet, black troupes particularly excelled. One of the most successful black minstrel companies was Sam Hague's Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels, managed by Charles Hicks. This company eventually was taken over by Charles Callendar. The Georgia Minstrels toured the United States and abroad and later became Haverly's Colored Minstrels.

African-American blackface productions also contained buffoonery and comedy, by way of self-parody. In the early days of African-American involvement in theatrical performance, blacks could not perform without blackface makeup, regardless of how dark-skinned they were, but blackface minstrelsy was a practical and often relatively lucrative livelihood when compared to the menial labor to which most blacks were relegated. Owing to the discrimination of the day, "corking (or "blacking") up" provided an often singular opportunity for African-American musicians, actors, and dancers to practice their crafts. Some minstrel shows, particularly when performing outside the South, also managed subtly to poke fun at the racist attitudes and double standards of white society or champion the abolitionist cause. It was through blackface performers, white and black, that the richness and exuberance of African-American music, humor, and dance first reached mainstream, white audiences in the U.S. and abroad.

Blackface remained a popular theatrical device well into the 20th century, crossing over from the minstrel troupe touring circuit to vaudeville, to motion pictures, then to television. In the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA), an all-black vaudeville circuit organized in 1909, blackface acts were a popular staple. Called "Toby" for short, performers also nicknamed it "Tough on Black Actors" (or, variously, "Artists" or "Asses"), because earnings were so meager. Still, TOBA headliners like Tim Moore and Johnny Hudgins could make a very good living, and even for lesser players, TOBA provided fairly steady, more desirable work than generally was available elsewhere. Blackface served as a springboard for hundreds of artists and entertainers—black and white—many of whom later would go on to find work in other performance traditions. In fact, one of the most famous stars of Haverly's European Minstrels was Sam Lucas, who became known as the "Grand Old Man of the Negro Theatre". It was Lucas who later played the title role in the first cinematic production of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin.

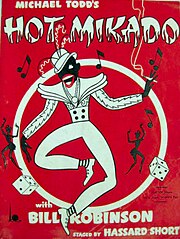

Many well-known entertainers of stage and screen also performed in blackface, including Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Bing Crosby and Bob Hope, as well as actor and comedian Bert Williams, who was the first black performer in vaudeville and on Broadway. But apart from cultural references such as those seen in theatrical cartoons, onstage blackface essentially was eliminated in the U.S. post-vaudeville, when public sensibilities regarding race began to change and blackface became increasingly associated with racism and bigotry.

Blackface and darky iconography

The darky icon itself—googly-eyed, with inky skin; exaggerated white, pink or red lips; and bright, white teeth—became a common motif first in the U.S., then worldwide, in entertainment, children's literature, mechanical banks and other toys and games of all sorts, cartoons and comic strips, advertisements, jewelry, textiles, postcards, sheet music, food branding and packaging, and other consumer goods.

In 1895, the Golliwogg surfaced in Great Britain, the product of American-born children's book illustrator Florence Kate Upton, who modeled her rag doll character Golliwogg after a minstrel doll she had in the U.S. as a child. "Golly", as he later affectionately came to be called, had a jet-black face; wild, woolly hair; bright, red lips; and sported formal minstrel attire. The generic British golliwog later made its way back across the Atlantic as dolls, toy tea sets, ladies' perfume and in a myriad of other forms. Lexicographers consider it likely that the word golliwog was the origin of the ethnic slur wog.

American darky images and Upton's minstrel-doll-inspired Golliwogg had a profound influence on the way blacks were depicted worldwide. Black and white minstrel troupes toured Europe and were somewhat successful for a time. As in the U.S., there was a history of involvement in the trans-Atlantic slave trade, and an ongoing European colonial presence in Africa and the Caribbean, as well. Shared notions of white supremacy likely contributed to the popularity of darky iconography, which proliferated on both sides of the Atlantic. Unlike in the United States, however, in Europe and Asia, scant resident populations of people of black African descent likely posed little challenge to the racist attitudes of the day. As a result, blackface and darky iconography and the stereotypes they perpetuated prompted no notable objections and, consequently, sensibilities regarding them often have been very different from those in America. For Europeans and Asians, many of whom had never seen a black person in the flesh before World War II, the iconography of the blackface darky, as in the United States, became commonly accepted and widely used to depict blacks. Internationally, darky icons proliferated far beyond the minstrel stage and, for many non-blacks, became reified in the human beings they caricatured. The grinning, pop-eyed distortions acquired a life of their own. By the 1920s and '30s, for example, French posters advertising performances by even respected performers such as Josephine Baker and Bill "Bojangles" Robinson routinely were in the darky mold. After the Second World War, Japan flooded the U.S. with darky and mammy kitchenware, ashtrays, toys, and ceramics.[citation needed]

U.S. cartoons from the 1930s and 1940s often featured characters in blackface gags as well as other racial and ethnic caricatures. Blackface was one of the influences in the development of characters like Mickey Mouse.[5] The United Artists 1933 release "Mickey's Mellerdrammer" — the name a corruption of "melodrama" thought to harken back to the earliest minstrel shows — was a film short based on a production of Uncle Tom's Cabin by the Disney characters. Mickey, of course, was already black, but the advertising poster for the film shows Mickey with exaggerated, orange lips; bushy, white sidewhiskers; and his now trademark white gloves.

In the U.S., by the 1950s, the NAACP had begun calling attention to such portrayals of African Americans and mounted a campaign to put an end to blackface performances and depictions. For decades, darky images had been seen in the branding of everyday products and commodities such as Picaninny Freeze, the Coon Chicken Inn[6] restaurant chain and the like. With the eventual successes of the modern day Civil Rights Movement, such blatantly racist branding practices ended in the U.S., and blackface became an American taboo.

Modern-day manifestations

Over time, blackface and darky iconography became artistic and stylistic devices associated with art deco and the Jazz Age. By the 1950s and '60s, particularly in Europe, where it was more widely tolerated, blackface became a kind of outré, camp convention in some artistic circles. The Black and White Minstrel Show was a popular British musical variety show that featured blackface performers, and remained on British television until 1978. Actors and dancers in blackface appeared in music videos such as Taco's "Puttin' on the Ritz" and Grace Jones's "Slave to the Rhythm", which aired regularly on MTV during the 1980s.

Darky iconography, while generally considered taboo in the U.S., still persists around the world. When trade and tourism produce a confluence of cultures, bringing differing sensibilities regarding blackface into contact with one another, the results can be jarring. Darky iconography is still popular in Japan today, but when Japanese toymaker Sanrio Corporation exported a darky-icon character doll in the 1990s, the ensuing controversy prompted Sanrio to halt production. Foreigners visiting the Netherlands in November and December are often shocked at the sight of whites in classic blackface as a character known as Zwarte Piet, whom many Dutch nationals love as a holiday symbol. Travelers to Spain have expressed dismay at seeing "Conguito",[7] a tubby, little brown character with full, red lips, as the trademark for Conguitos, a confection manufactured by the LACASA Group. In Britain, "Golly",[8] a golliwog character, finally fell out of favor in 2001 after almost a century as the trademark of jam producer James Robertson & Sons; but the debate still continues whether the golliwog should be banished in all forms from further commercial production and display, or preserved as a treasured childhood icon. The influence of blackface on branding and advertising, as well as on perceptions and portrayals of blacks, generally, can be found worldwide. Black and brown products, particularly, such as licorice and chocolate, remain commodities most frequently paired with darky iconography.

The Netherlands' Zwarte Piet

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

Zwarte Piet, or "Black Peter", is a character in Dutch and Flemish Sinterklaas lore who assists Sinterklaas whose feast, mainly targeted at children, is celebrated December 5. Some sources indicate that Zwarte Piet originally was an enslaved devil, rather than a Moor[9]. Once portrayed realistically, Zwarte Piet became a classic darky icon in the mid-to-late 19th century, contemporaneous with the spread of darky iconography. To this day, holiday revellers in the Netherlands blacken their faces, wear afro wigs and bright red lipstick, and walk the streets throwing candy to passersby. Some of the actors behave dim-wittedly, or like buffoons, and/or speak mangled Dutch as embodiments of Zwarte Piet.[10]

Accepted in the past without controversy in a once largely ethnically homogeneous nation, today Zwarte Piet is controversial and greeted with mixed reactions. Many see him as a cherished tradition and look forward to his annual appearance. Others detest him—perhaps most notably, some of the country's people of color. The lyrics of traditional Sinterklaas songs and some parents warn that Zwarte Piet will leave well-behaved children presents, but punish those who have been naughty. Zwarte Piet will kidnap bad children and carry them off in his sack to his homeland of Spain, where, legend has it, he and Sinterklaas dwell out of season. Consequently, while many Dutch children love and are fascinated by him, some are fearful of encounters with Zwarte Piet impersonators.[11]

Writing in Essence magazine of her experiences living in the Netherlands, expatriate African American Pamela Armstrong-De Vreeze observed that the "annual pageant introduces a troubling minstrel-show stereotype to young Dutch children, whose exposure to Blacks is often limited to the Zwarte Piet character. As a result, many can't tell the difference between a made-up Zwarte Piet and a person of African descent."[12]

Blackfaced, googly-eyed, red-lipped Zwarte Piet dolls, die cuts and displays adorn store windows alongside brightly displayed, smartly packaged holiday merchandise.[13] Foreign tourists, particularly Americans, are often bewildered and mortified. As a result of the allegations of racism, some have replaced Zwarte Piet's blackface makeup with face paint in alternative colors such as green or purple. This practice, however, has not caught on. So, at least once a year in the Netherlands, the debate over the harmlessness, or racism, of Zwarte Piet resurfaces—along with the usual smiling golliwog dolls; strolling Zwarte Pieten tossing sweets to eager children and other passersby; and the sometimes startling storefront-darky images.

The "coons" of Cape Town and Auckland

Inspired by blackface minstrels who visited Cape Town, South Africa, in 1848, former Javan and Malaysian slaves took up the minstrel tradition, holding emancipation celebrations which consisted of music, dancing and parades. In the African-American cakewalk tradition, their songs often parodied their former masters and the privileged, white class. Such celebrations eventually became consolidated into an annual, year-end event known as the Cape Coon Carnival.

Today, carnival minstrels are mostly Coloured ("mixed race"), Afrikaans-speaking revellers. Often in a pared-down style of blackface which exaggerates only the lips, they parade down the streets of the city in colorful costumes, in a celebration of Creole culture. Participants also pay homage to the carnival's African-American roots, playing Negro spirituals and jazz featuring traditional Dixieland jazz instruments, including horns, banjos, and tambourines.[14]

Over time, carnival participants have appropriated the term coon and don't regard it as a pejorative. However, city officials changed the name of the celebration to the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival in 2003, so as to avoid offending tourists. Former South African president Nelson Mandela endorsed the carnival in 1986, and is a member of the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival Association, which presides over the event. Now officially more than a hundred years old, the carnival has become a major tourist attraction, vigorously promoted by the nation's tourism authority, complete with corporate sponsorship.

A multi-ethnic group of New Zealanders, taking their cue from the Cape Town tradition, have started their own "Cape Coon troupe", calling themselves the "Auckland City Dukes". Wearing modified minstrel attire and modified blackface similar to that of their Cape Town counterparts, the Dukes participate in the annual Cape Town Minstrel Carnival and enthusiastically embrace the "coon" moniker.

In the U.S.

The darky, or coon, archetype that blackface played such a profound role in creating remains a persistent thread in American culture. It continues to resurface. Animation utilizing darky iconography aired on U.S. television routinely as late as the mid-1990s, and still can be seen in specialty time slots on such networks as TCM. In 1993, white actor Ted Danson ignited a firestorm of controversy when he appeared at a Friars Club roast in blackface, delivering a risqué shtick written by his then love interest, African-American comedienne Whoopi Goldberg. Recently, gay white performer Chuck Knipp has used drag, blackface, and broad racial caricature while portraying a character named "Shirley Q. Liquor" in his cabaret act, generally performed for all-white audiences. Knipp's outrageously stereotypical character has drawn criticism and prompted demonstrations from black gay and transgender activists.[15]

In New Orleans in the early 1900s, a group of African American laborers began a marching club in the annual Mardi Gras parade, dressed as hobos and calling themselves "The Tramps". Wanting a flashier look, they later renamed themselves "Zulus" and copied their costumes from a blackface vaudeville skit performed at a local black jazz club and cabaret.[16] The result is one of the best known and most striking krewes of Mardi Gras, the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Dressed in grass skirts, top hats and exaggerated blackface, the Zulus of New Orleans are controversial as well as popular.

Former Illinois congressman and House Republican party minority leader Bob Michel caused a minor stir in the early 1990s, when he fondly recalled minstrel shows in which he had participated as a young man and expressed his regret that they had fallen out of fashion.

Blackface and minstrelsy also serve as the theme of Spike Lee's film Bamboozled (2000). It tells of a black television executive who reintroduces the old blackface style and is horrified by its success.

In November 2005, controversy erupted when African American journalist Steve Gilliard posted a photograph on his blog. The image was of black Republican Maryland lieutenant governor Michael S. Steele, then a candidate for U.S. Senate. It had been doctored to include bushy, white eyebrows and big, red lips. The caption read, "I's simple Sambo and I's running for the big house." Gilliard defended the image, commenting that the politically conservative Steele has "refused to stand up for his people."[17]

Further, commodities bearing iconic darky images, from tableware, soap and toy marbles to home accessories and T-shirts, continue to be manufactured and marketed in the U.S. and elsewhere. Some are reproductions of historical artifacts, while others are so-called "fantasy" items, newly designed and manufactured for the marketplace. There is a thriving niche market for such items in the U.S., particularly, as well as for original artifacts of darky iconography. The value of many vintage pieces has skyrocketed since the 1970s.

Blackface minstrelsy and world popular culture

Despite its racist portrayals, blackface minstrelsy was the conduit through which African-American and African-American-influenced music, comedy, and dance first reached the American mainstream. It played a seminal role in the introduction of African-American culture to world audiences. Wrote jazz historian Gary Giddings in Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams, The Early Years 1903–1940:

Though antebellum (minstrel) troupes were white, the form developed in a form of racial collaboration, illustrating the axiom that defines—and continues to define—American music as it developed over the next century and a half: African-American innovations metamorphose into American popular culture when white performers learn to mimic black ones.

Virtually every major, new genre of popular music in the United States from the twilight of the 19th century to the dawn of the 21st century—from the tight harmonies of barbershop quartets to ragtime, to blues, to jazz and swing, to blues, rhythm and blues and rock and roll, to funk and classic rock, to hip hop and country— is a product or byproduct of African-American innovation.[18] Indeed, the broad spectrum of popular music as it exists today would be unrecognizable absent the influence of African-American culture. Standard early jazz tunes included numbers such as "The Darktown Strutters Ball", a song about the slave cakewalk tradition, and "The Birth of the Blues". Even into the '50s, R&B artists from Louis Jordan (in, for example, "Saturday Night Fish Fry") to the Dominoes (in "The Deacon is Moving In") harkened back to minstrelsy. A lot of vaudeville shtick, and its earliest comedians, musicians and actors as well, were transplants from the blackface minstrel tradition—among them Laugh-In's Pigmeat Markham. The radio antics of "Amos 'n' Andy", which featured white actors impersonating blacks, were straight from the minstrel stage. The popular radio show lasted more than a decade and then moved to television, utilizing black actors, in 1951. Under fire from critics as being demeaning to blacks, it ran only two years.

While not commonly associated today with country and bluegrass music, genres not dominated by black performers, African Americans exerted a strong, early influence on the development of both through the introduction of the banjo, as well as through the innovation of musical techniques in the playing of both the banjo and fiddle.[19][20] Many traditional hillbilly fiddle tunes, including "Turkey in the Straw" and "Old Dan Tucker" came from minstrelsy.[21] Further, in format and content, the still running Grand Ole Opry radio show mirrors blackface minstrel shows, and, notes Cockrell, Hee Haw "in structure, humor, characterization, and, in many ways, music, was a minstrel show in 'rube face'". And as with jazz, many of country’s earliest stars, such as Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills, were veterans of blackface performance.

The immense popularity and profitability of blackface were testaments to the power, appeal, and commercial viability of not only black music and dance, but also of black style. This led to cross-cultural collaborations, as Giddings writes; but, particularly in times past, to the often ruthless exploitation and outright theft of African-American artistic genius, as well— by other, white performers and composers; agents; promoters; publishers; and record company executives. The precedent set by blackface, of aggressive white exploitation and appropriation of black culture, is alive today in, for example, the anointed, white, so-called "royalty" of essentially African-American music forms: Benny Goodman, widely known as the "King of Swing"; Paul Whiteman, who called himself the "King of Jazz"; Elvis Presley, known as the "King of Rock and Roll"; and Janis Joplin, crowned by some "Queen of the Blues".

For more than a century, when white performers have wanted to appear sexy, (like Elvis); or streetwise, (like Eminem);[22] or hip, (like Mezz Mezzrow);[23] or cool, (like actors Marlon Brando and James Dean[24] and, more recently, John Travolta and George Clooney);[25] or urbane, (like Frank Sinatra), they often have turned to indigenously African-American performance styles, stage presence and personas. Sometimes this has been done out of genuine admiration, as in the case of blues revivalists. Sometimes it is done with a good deal of calculation by, for example, the many white lead performers, such as Amy Winehouse, who use black backup singers or musicians. Pop culture referencing and cultural appropriation of African-American performance and stylistic traditions—often resulting in tremendous profit—is a tradition with origins in blackface minstrelsy.

The international imprint of African-American culture is pronounced in its depth and breadth, in indigenous expressions, as well as in myriad, blatantly mimetic and subtler, more attenuated forms. This "browning", à la Richard Rodriguez, of American and world popular culture began with blackface minstrelsy.[citation needed] It is a continuum of pervasive African-American influence which has many prominent manifestations today, among them the ubiquity of the cool aesthetic][26] and hip hop culture.[27]

Face paint and ethnic impersonation

Related types of performances are yellowface, in which performers adopt Asian identities, brownface, for East Indian or non-white Latino, and redface, for Native Americans. Whiteface, or paleface, is sometimes used to describe non-white actors performing white parts (for example, in the film White Chicks), although it more commonly describes the clown or mime traditions of white makeup. Dooley Wilson, famous for the role of Sam the piano player in Casablanca, earned his stage name "Dooley" from performing in whiteface as an Irishman.

In Thailand, actors darken their faces to portray the The Negrito of Thailand in a popular play by King Chulalongkorn (1868–1910), Ngo Pa (Template:Lang-th, which has been turned into a musical and a movie.[28]

See also

- Amos 'n' Andy

- Bamboozled — 2000 Spike Lee film featuring blackface

- The Black and White Minstrel Show — a British BBC television series (1958–1978)

- Blackface minstrel songs, list of

- Blackface minstrel troupes, list of

- Censored Eleven

- Cool (aesthetic)

- Coon song

- Cultural appropriation

- Entertainers known to have performed in blackface, list of

- Gollywog

- Jynx- a controversial Pokémon

- Little Black Sambo

- Little Britain, a British comedy show that has used blackface in sketches

- Memín Pinguín

- Mickey Mouse

- Minstrel show

- Mr. Popo

- Papa Lazarou

- Shirley Q. Liquor

- Two Black Crows

- Young and Innocent — 1937 Alfred Hitchcock movie

Compare

- Border Morris, a traditional English male folk dance tradition from the borders of England and Wales

- Ganguro, a fashion trend among Japanese girls

Notes

- ^ Inside the minstrel mask: Readings in nineteenth-century blackface minstrelsy by Bean, Annemarie, James V. Hatch, and Brooks McNamara. 1996. Middletown, CT: Wesleyen University Press.

- ^ Color-Blind Ideology and the Cultural Appropriation of Hip-Hop Jason Rodriquez, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, Vol. 35, No. 6, 645-668 (2006)

- ^ Darktown Strutters. - book reviews African American Review, Spring, 1997 by Eric Lott

- ^ Twain, Mark (1906). Chapters from my Autobiography. Harper & Brothers.

- ^ Sacks and Sacks 158.

- ^ Coon Chicken Inn Photos and history of the restaurant chain.

- ^ "Conguitos".

- ^ "The African-American Image Abroad: Golly, It's Good!".

- ^ "Santa Claus: Who Is He Anyway?". Retrieved 2006-10-06.

- ^ "Black Pete: Analyzing a Racialized Dutch Tradition Through the History of Western Creations of Stereotypes of Black Peoples" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ "Surviving Zwarte Piet - a Black mother in the Netherlands copes with a racist institution in Dutch culture, Essence". December 1997.

- ^ "Surviving Zwarte Piet - a Black mother in the Netherlands copes with a racist institution in Dutch culture, Essence". December 1997.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Blackface Drag Again Draws Fire Gay City News. VOLUME 3, ISSUE 308 | February 19 - 25, 2004

- ^ Zulu Blackface: The Real Story!

- ^ [3]

- ^ For jazz, swing, and rock, see Watkins, Mel (1999). On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy. Lawrence Hill Books, p. 82. For ragtime, see Watkins, p. 143. For rhythm and blues, see Watkins, p. 334. For barbershop, see Nicholls, David, ed. (1998). The Cambridge History of American Music. Cambridge University Press, p. 297. For blues, see Nicholls, p. 125. For ragtime and jazz, see Nicholls, p. 48. For rock and country, see Nicholls 347. For funk, see Nicholls, p. 360. For hip hop, see Nicholls, p. 268. For bluegrass, see Cantwell, Robert (2003). Bluegrass Breakdown: The Making of the Old Southern Sound. University of Illinois Press, p. xvi.

- ^ Cantwell, p. 91; Nathan, Hans (1962). Dan Emmett and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy. University of Oklahoma Press, p. 207-8.

- ^ Conway, Cecelia (2005). African Banjo Echoes in Appalachia. The University of Tennessee Press. p. 424.

- ^ Lott, p. 16, 173.

- ^ Cunningham, Daniel Mudie. "Larry Clark: Trashing the White American Dream." The Film Journal. Retrieved on 2006-08-25

- ^ Roediger, David (1997). "The First Word in Whiteness: Early Twentieth-Century European Immigration", Critical White Studies: Looking Behind the Mirror. Temple University Press, p. 355.

- ^ "Frank Houston The Dearth of Cool." salon.com. November 1, 1999. Retrieved on 2006-08-25

- ^ Southerland, Julie. "A Discussion of Women and the "White Negro" in Hip-Hop." Left Hook. Retrieved 2006-09-27

- ^ Southgate, Nick."Coolhunting, account planning and the ancient cool of Aristotle." Marketing Intelligence and Planning, Vol. 21, Issue 7, pp. 453-461, 2003. Retrieved on 03-02-2007.

- ^ MacBroom, Patricia. "Rap Locally, Rhyme Globally: Hip-Hop Culture Becomes a World-Wide Language for Youth Resistance, According to Course." News, Berkeleyan. 2000-05-02. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ^

Keyes, Charles F. (1995). The golden peninsula : culture and adaptation in mainland Southeast Asia. Includes bibliographical references and index. Honolulu: (SHAPS library of Asian studies) University of Hawai'i Press. pp. p. 34. ISBN 082481696x.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help)

References

- Armstron-De Vreeze, Pamela (1997). ""Surviving Zwarte Piet — a Black mother in the Netherlands copes with a racist institution in Dutch culture"". Essence magazine. Retrieved 2005-11-15.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Hughes, Langston and Meltzer, Milton (1967). Black Magic: A Pictorial History of Black Entertainers in America. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-306-80406-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Inns, George (producer) (June 1958–July 1978). "The Black and White Minstrel Show". BBC. Retrieved 2005-11-15.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507832-2.

- Sacks, Howard L, and Sacks Judith (1993). Way up North in Dixie: A Black Family's Claim to the Confederate Anthem. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6300-5.

- Twain, Mark (1924). "XIX, dictated 1906-11-30". Mark Twain's Autobiography. New York: Albert Bigelow Paine. LCCN 24025122.

- Watkins, Mel (1994). On the Real Side: Laughing, Lying, and Signifying—The Underground Tradition of African-American Humor that Transformed American Culture, from Slavery to Richard Pryor. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-68982-7.

Bibliography

- Cockrell, Dale and Wilmeth, Don B. (1997). Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and their World. Cambridge Studies in American Theatre and Drama. ISBN 0-521-56828-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fox, Anna (1999). Zwarte Piet. Black Dog. ISBN 1-901033-86-4.

- Henderson, Stephen (1972). Understanding the New Black Poetry. William Morrow and Company.

- Levinthal, David (1999). Blackface. Arena. ISBN 1-892041-06-5.

- Lhamon, Jr., W.T. (1998). Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-74711-9.

- Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509641-X.

- Various authors (1999). Matthews, Gerald E. (editor) (ed.). Journey Towards Nationalism: The Implications of Race and Racism. New York: Farber. ISBN 0-8281-1334-3.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Rogin, Michael (1998). Blackface, White Noise: Jewish Immigrants in the Hollywood Melting Pot. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21380-7.

External links

General

- "Auckland gets its own Cape Coon troupe" from the SANZ Charitable Trust

- Blackface and other historic racial images from the Authentic History Center

- "Bambizzoozled - Blackface in Movies and Television"

- "Banned Cartoons" from Rotten.com

- The Black and White Minstrel Show from the Museum of Broadcast Communications

- "The Blackface Stereotype", Manthia Diawara

- "Coon Carnival, Cape Town" from Africape Tours

- "Nigger and Caricatures", Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, from Ferris State University

- Recent blackface stories in the news, from the Colorblind Society

- "Zulu Blackface: The Real Story!"

Zwarte Piet

- Zwarte Piet? - Boom Chicago rap video satire of Run DMC's "Christmas in Hollis"

- "Dutch Sinterklaas and Zwarte Piet: innocent fun or a racist tradition?", Wispr, Wageningen international student paper, 2002/34

- Expatica's Dutch News in English: Annual Zwarte Piet Debate

- "Man, I Don't 'Get' Zwarte Piet" from "Downwind of Amsterdam"

- "Who is Black Peter?" from Ferris State University

- Zwarte Piet film by Adwa Foundation, Rotterdam, and the Global Afrikan Congress

- Zwarte Piet (in Dutch)

- "Zwarte Piet — a sinister symbol in a 'tolerant' country" from Expatica.com