Puerto Rico: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 126: | Line 126: | ||

==Puerto Rican Migration to the United States== |

==Puerto Rican Migration to the United States== |

||

The massive migration of Puerto Rican immigrants |

The massive migration of Puerto Rican immigrants the United States was the largest in the early and late 20th century. This was a result of a long history of [[colonialism]] of Puerto Rico. From the first Spanish invasion of Puerto Rico in the early 1500s, until the occupation by the United States in 1898, Puerto Rico’s sovereignty has ever since laid in the hands of the U.S. The largest influx in numbers was in [[East Harlem]], New York in the 1950s all the way up to 1980s. These great numbers created this strong visible enclave. |

||

From the Spanish invasion in 1508, the Puerto Rican population has been under the influence of colonial powers. The struggle for independence remains. Ever since Spanish rule, Puerto Ricans have always settled in the U.S. to earn their livings. It was not until the end of the Spanish Cuban-American War in 1898 that the huge influx of Puerto Rican workers to the U.S had begun. In 1898 the end of the [[Spanish-American War]], the United States acquired Puerto Rico and has retained sovereignty ever since. Puerto Rico’s colonial ruler changed, and migration now from the colony to the metropolis has increased. The declaration by U.S. congress in 1917 made the move easier. In 1917 U.S. congress declared all Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens, enabling a migration free from all immigration barriers, this occurred through the [[Jones-Shafroth Act]]. U.S. political and economic interventions in Puerto Rico created the conditions for emigration, "by concentrating wealth in the hands of U.S. corporations and displacing workers." (Padilla, 31) The long history of colonization of Puerto Rico created dislocation, forcing Puerto Ricans to relocate to [[New York City]]. |

From the Spanish invasion in 1508, the Puerto Rican population has been under the influence of colonial powers. The struggle for independence remains. Ever since Spanish rule, Puerto Ricans have always settled in the U.S. to earn their livings. It was not until the end of the Spanish Cuban-American War in 1898 that the huge influx of Puerto Rican workers to the U.S had begun. In 1898 the end of the [[Spanish-American War]], the United States acquired Puerto Rico and has retained sovereignty ever since. Puerto Rico’s colonial ruler changed, and migration now from the colony to the metropolis has increased. The declaration by U.S. congress in 1917 made the move easier. In 1917 U.S. congress declared all Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens, enabling a migration free from all immigration barriers, this occurred through the [[Jones-Shafroth Act]]. U.S. political and economic interventions in Puerto Rico created the conditions for emigration, "by concentrating wealth in the hands of U.S. corporations and displacing workers." (Padilla, 31) The long history of colonization of Puerto Rico created dislocation, forcing Puerto Ricans to relocate to [[New York City]]specifically, with the exception of other cities such as Tampa Bay, Philadelphia, and Florida. |

||

[[Philippe Bourgois]], a well-known activist of Puerto Ricans in the inner city suggests that "the Puerto Rican community has feel victim to poverty through social marginalization due to the transformation of New York into a global city." Scholars argue that the elimination of the manufacturing sector to a more profitable service sector, forced a loss of jobs, and this struggle to assimilate into the larger New York City population, often citing the creation of class distinction and racism in the community. |

[[Philippe Bourgois]], a well-known activist of Puerto Ricans in the inner city suggests that "the Puerto Rican community has feel victim to poverty through social marginalization due to the transformation of New York into a global city." Scholars argue that the elimination of the manufacturing sector to a more profitable service sector, forced a loss of jobs, and this struggle to assimilate into the larger New York City population, often citing the creation of class distinction and racism in the community. |

||

The Puerto Rican population |

The Puerto Rican population in East Harlem remains the most poor amongst all immigrant groups within U.S. cities. As of 1973 about “46.2% of the Puerto Rican Migrants in East Harlem were living below the federal poverty line.” (Salas, 12) As of 1990, The Puerto Rican niche was the largest immigrant group within the United States. The struggle for legal work and affordable housing remains fairly low and the implementation of public policy remains fairly inconsistent. It is often considered that the transformation of the U.S. economy in 1973 and the 1980s mostly affected the entire Puerto Rican population of East Harlem. |

||

Policymakers promoted "colonization plans and contract labour programs to reduce the population. U.S. employers, often with government support, recruited Puerto Ricans as a source of low-wage labour to the United States and other destinations.“(Davila, 40) Notably, this was not the case. Jobs were allocated to the heart of the city, not the inner city. |

Policymakers promoted "colonization plans and contract labour programs to reduce the population. U.S. employers, often with government support, recruited Puerto Ricans as a source of low-wage labour to the United States and other destinations.“(Davila, 40) Notably, this was not the case. Jobs were allocated to the heart of the city, not the inner city. |

||

Revision as of 16:40, 23 November 2007

Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico Commonwealth of Puerto Rico | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Latin: Joannes Est Nomen Eius Spanish: Juan es su nombre (English: "John is his name") | |

| Anthem: "La Borinqueña" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | San Juan |

| Official languages | Spanish and English |

| Demonym(s) | Puerto Rican |

| Government | Republican three-branch type of government |

| Area | |

• Total | 9,104 km2 (3,515 sq mi) (169th) |

• Water (%) | 1.6 |

| Population | |

• July 2007 estimate | 3,994,259 (127th in the world; 27th in the United States) |

• 2000 census | 3,913,054 |

• Density | 438/km2 (1,134.4/sq mi) (21st in the world; 3rd in the United States) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate |

• Total | $86.5 billion (N/A) |

• Per capita | $22,058 (N/A) |

| Currency | United States dollar (USD) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (No DST) |

| Calling code | 1 |

| ISO 3166 code | PR |

| Internet TLD | .pr |

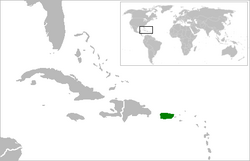

Puerto Rico, officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico (Template:Lang-es) is a partially self-governing unincorporated territory of the United States with Commonwealth status.[1][2] It is located in the northeastern Caribbean, east of the Dominican Republic and west of the Virgin Islands; approximately 1,280 miles (2,000 km) off the coast of Florida (the nearest of the mainland United States). The archipelago of Puerto Rico includes the main island of Puerto Rico, the smallest of the Greater Antilles, and a number of smaller islands and keys, the largest of which are Mona, Vieques, and Culebra. Puerto Ricans sometimes refer to their island as Borikén, or the Spanish variant Borinquen, a name for the island used by indigenous Taíno people. The current term boricua derives from the Taíno name for the island, and is commonly used to identify oneself as Puerto Rican.

Even though all people born in Puerto Rico are statutory U.S. citizens, the nature of Puerto Rico's political relationship with the United States is the subject of ongoing debate on the island, in the United States Congress, and in the United Nations.[3][4] According to a President's Task Force report,[5] Puerto Rico is an unincorporated organized territory of the United States, subject to the plenary powers of the U.S. Congress and with the right to establish a constitution for the internal administration of government and on matters of purely local concern.

History

Pre-Columbian era

The history of the island of Puerto Rico (Spanish for "rich port") before the arrival of Christopher Columbus is not well understood. What is known today comes from findings and from early Spanish accounts. The first comprehensive book on the history of Puerto Rico was written by Fray Iñigo Abbad y Lasierra in 1786, 293 years after the first Spaniards arrived on the island.[6]

The first indigenous settlers of Puerto Rico were the Ortoiroid, an Archaic age culture. An archaeological dig in the island of Vieques in 1990 found the remains of what is believed to be an Arcaico (Archaic) man (named Puerto Ferro man) which was dated to around 2000 BCE.[7] Between CE 120 and 400, the Igneri, a tribe from the Orinoco region, arrived on the island.[8] Between the 7th and 11th century the Taíno culture developed on the island and, by approximately CE 1000, the Taíno culture had become dominant, a trend that lasted until the Spanish arrived in 1493.

Spanish colony

When Christopher Columbus arrived at Puerto Rico during his second voyage on November 19, 1493, the island was inhabited by a group of Arawak Indians known as Taínos. The Taínos called the island "Borikén" or "Borinquen".[9] Columbus named the island San Juan Bautista, in honor of Saint John the Baptist. Later the island took the name of Puerto Rico (Template:Lang-en) while the capital was named San Juan. It is estimated that there may have been as many as 250,000 Tainos in the Caribbean when the Spanish first arrived. In 1508, Spanish conquistador Juan Ponce de León became the island's first governor to take office.[10]

The island was soon colonized by the Spanish. Taínos were forced into slavery by the Spanish crown but were decimated by diseases brought by the Spaniards and the harsh conditions in which they were forced to work. African slaves were introduced as labor to replace the decreasing populations of Taíno. Puerto Rico soon became an important stronghold and port for the Spanish Empire in the Caribbean, gaining the title of "La Llave de las Americas" (The Key of the Americas). Colonial emphasis during the late 17th - 18th centuries, however, focused on the more prosperous mainland territories, leaving the island impoverished of settlers. By the beginning of the 18th century the Taino Indians had been reduced to less than 10,000 people primarily inhabiting the central mountainous region (Las Cordillas) of Puerto Rico comprising the areas currently consisting of the municipalities of Orocovis, Morovis, Ciales and Corozal. A prominent resident of this early period was Bernardo de Balbuena, Bishop of Puerto Rico, who wrote Baroque poetry extolling the beauty of the New World, especially Mexico. Many of his manuscripts were burned by Dutch pirates when they sacked the island in 1625.

Because of concerns of threats from European enemies, over the centuries various forts and walls, such as La Fortaleza, El Castillo San Felipe del Morro and El Castillo de San Cristóbal, were built to protect the port of San Juan. The French, Dutch and English made several attempts to capture Puerto Rico but failed to wrest long-term occupancy of the island.

In 1809, while Napoleon occupied the majority of the Iberian peninsula, a populist assembly based in Cádiz recognized Puerto Rico as an overseas province of Spain with the right to send representatives to the Spanish Court. The representative Ramon Power y Giralt died soon after arriving in Spain. These constitutional reforms were reversed when autocratic monarchy was restored. Nineteenth century reforms augmented the population and economy, and expanded the local character of the island. After the rapid gains of independence by the South and Central American states in the first part of the century, Puerto Rico and Cuba became the sole New World remnants of the large Spanish empire.

Toward the end of the 19th century, poverty and political estrangement with Spain led to a small but significant two-day-long uprising in 1868 known as "Grito de Lares". The uprising, which began in the rural town of Lares, Puerto Rico was easily and quickly crushed when revolutionary forces expanded to the neighboring town of San Sebastian, Puerto Rico. Leaders of this independence movement included Ramón Emeterio Betances, considered the "father" of the Puerto Rican nation, and other political figures such as Segundo Ruiz Belvis. Later, another political stronghold was the autonomist movement originated by Román Baldorioty de Castro and, toward the end of the century, by Luis Muñoz Rivera. In 1897, Muñoz Rivera and others persuaded the liberal Spanish government to agree to a Charters of Autonomy for Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The following year in 1897, Puerto Rico's first, but short-lived, autonomous government was organized as an 'overseas province' of Spain. The charter maintained a governor appointed by Spain, which held the power to annul any legislative decision it disagreed with, and a partially elected parliamentary structure. In February of 1898, Governor General Manuel Macías inaugurated the new government under the Autonomous Charter, this gave town councils complete autonomy in local matters. Subsequently, the governor had no authority to intervene in civil and political matters unless authorized to do so by the Cabinet. General elections were held in March and on July 17,1898. Puerto Rico's autonomous government began to function, but not for long.[11] [12] [13]

Puerto Rico under United States sovereignty

On July 25, 1898 during the Spanish–American War, Puerto Rico was invaded by the United States with a landing at Guánica. Following the outcome of the war, Spain ceded Puerto Rico, along with Cuba, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States under the Treaty of Paris.[14] Puerto Rico began the twentieth century under the military rule of the United States with officials, including the governor, appointed by the President of the United States. The Foraker Act of 1900 had given Puerto Rico a certain amount of popular government including a popularly-elected House of Representatives. By 1917, the Jones-Shafroth Act granted U.S. citizenship to Puerto Ricans - a status they still hold today - and provided for a popularly-elected Senate to complete a bicameral elected Legislative Assembly. Until the first gubernatorial election in 1948, the Presidency of the Senate and the Resident Commissioner seat in Congress were held by Puerto Rico's top politicians. Many Puerto Ricans served in the U.S. Armed Forces beginning in World War I. Natural disasters, including a major earthquake and tsunami, and several hurricanes, and the Great Depression impoverished the island. Some political leaders demanded change; some, like Pedro Albizu Campos, would lead a nationalist (The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party) movement in favor of independence. He served many years in prison for seditious conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. Government in Puerto Rico.[15] Luis Muñoz Marín initially favored independence, but saw a severe decline of the Puerto Rican economy, as well as growing violence and uprisings and opted to support the "commonwealth" option instead. The "commonwealth" was supported before Luis Muñoz Marín by other political leaders. Change in the nature of the internal governance of the island came about during the later years of the Roosevelt–Truman administrations, as a form of compromise spearheaded by Muñoz Marín and others, and which culminated with the appointment by President Harry Truman in 1946 of the first Puerto Rican-born governor, Resident Commissioner Jesus T. Piñero. In 1947, the United States granted the right to democratically elect the governor of Puerto Rico. Senate President Luis Muñoz Marín became the first elected governor of Puerto Rico in the 1948 general elections, serving as such for 16 years, until 1964.

Starting at this time, there was heavy migration from Puerto Rico to the Continental United States, particularly New York City, in search of better economic conditions. Puerto Rican migration to New York displayed an average yearly migration that is summarized as follows: 1930-1940, 1,800 per year (avg.); 1946-1950, 31,000 per year; 1951-1960, 45,000 per year, including 75,000 in the peak year of 1953.[16] As of 2003, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that there are more people of Puerto Rican birth or ancestry living in the United States than in Puerto Rico itself.[17]

On November 1, 1950, Puerto Rican nationalists Griselio Torresola and Oscar Collazo attempted to assassinate President Harry S Truman. Subsequently, the Truman Administration allowed for a democratic referendum in Puerto Rico to determine whether Puerto Ricans desired to draft their own local constitution.[18] Puerto Rico adopted its own local constitution in July 25, 1952 which adopted the name of "Estado Libre Asociado" (Free Associated State), translated into English as Commonwealth, for the body politic and which continues to denote Puerto Rico's current relationship with the United States.[19][20] During the 1950s Puerto Rico experienced a rapid industrialization, due in large part to Operación Manos a la Obra ("Operation Bootstrap") (an offshoot of FDR's New Deal) which aimed to industrialize Puerto Rico's economy from agriculture-based into manufacturing-based.

Present-day Puerto Rico has become a major tourist destination and a leading pharmaceutical and manufacturing center. Still, Puerto Rico continues to struggle to define its political status. Three locally-authorized plebiscites have been held in recent decades to decide whether Puerto Rico should pursue independence, enhanced commonwealth status, or statehood. Narrow victories by commonwealth supporters over statehood advocates in the first two plebiscites and an unacceptable definition of Commonwealth by the pro statehood leadership on the ballots in the third has allowed the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States government to remain unchanged. In the latest status referendum of 1998, the "none of the above" option won over Statehood, a rejection by Commonwealthers of the definition of their status on the ballots, with 50.2% of the votes. Support for the pro-statehood party (Partido Nuevo Progresista or PNP) and the pro-commonwealth party (Partido Popular Democrático or PPD) remains about equal. The only registered independence party on the island, the Partido Independentista Puertorriqueño or PIP, usually receives 3-5% of the electoral votes, though there are several smaller independence groups like the Partido Nacionalista de Puerto Rico (Puerto Rican Nationalist Party), el Movimiento Independentista Nacional Hostosiano (National Hostosian Independence Movement), and the Macheteros - Ejercito Popular Boricua (or Boricua Popular Army).

On 25 October2006, the Puerto Rico State Department conferred to Juan Mari Brás Puerto Rico Citizenship. The Puerto Rico Supreme Court and the Puerto Rican Secretary of Justice determined that the Puerto Rican citizenship in fact exists and was recognized in the Constitution of Puerto Rico, as in the Insular Cases (Casos Insulares in Spanish) of 1901 through 1922 of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Puerto Rico State Department has developed, since the summer of 2007, the protocol to grant the Puerto Rican citizenship to Puerto Ricans[21]

Puerto Rican Migration to the United States

The massive migration of Puerto Rican immigrants the United States was the largest in the early and late 20th century. This was a result of a long history of colonialism of Puerto Rico. From the first Spanish invasion of Puerto Rico in the early 1500s, until the occupation by the United States in 1898, Puerto Rico’s sovereignty has ever since laid in the hands of the U.S. The largest influx in numbers was in East Harlem, New York in the 1950s all the way up to 1980s. These great numbers created this strong visible enclave.

From the Spanish invasion in 1508, the Puerto Rican population has been under the influence of colonial powers. The struggle for independence remains. Ever since Spanish rule, Puerto Ricans have always settled in the U.S. to earn their livings. It was not until the end of the Spanish Cuban-American War in 1898 that the huge influx of Puerto Rican workers to the U.S had begun. In 1898 the end of the Spanish-American War, the United States acquired Puerto Rico and has retained sovereignty ever since. Puerto Rico’s colonial ruler changed, and migration now from the colony to the metropolis has increased. The declaration by U.S. congress in 1917 made the move easier. In 1917 U.S. congress declared all Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens, enabling a migration free from all immigration barriers, this occurred through the Jones-Shafroth Act. U.S. political and economic interventions in Puerto Rico created the conditions for emigration, "by concentrating wealth in the hands of U.S. corporations and displacing workers." (Padilla, 31) The long history of colonization of Puerto Rico created dislocation, forcing Puerto Ricans to relocate to New York Cityspecifically, with the exception of other cities such as Tampa Bay, Philadelphia, and Florida.

Philippe Bourgois, a well-known activist of Puerto Ricans in the inner city suggests that "the Puerto Rican community has feel victim to poverty through social marginalization due to the transformation of New York into a global city." Scholars argue that the elimination of the manufacturing sector to a more profitable service sector, forced a loss of jobs, and this struggle to assimilate into the larger New York City population, often citing the creation of class distinction and racism in the community.

The Puerto Rican population in East Harlem remains the most poor amongst all immigrant groups within U.S. cities. As of 1973 about “46.2% of the Puerto Rican Migrants in East Harlem were living below the federal poverty line.” (Salas, 12) As of 1990, The Puerto Rican niche was the largest immigrant group within the United States. The struggle for legal work and affordable housing remains fairly low and the implementation of public policy remains fairly inconsistent. It is often considered that the transformation of the U.S. economy in 1973 and the 1980s mostly affected the entire Puerto Rican population of East Harlem.

Policymakers promoted "colonization plans and contract labour programs to reduce the population. U.S. employers, often with government support, recruited Puerto Ricans as a source of low-wage labour to the United States and other destinations.“(Davila, 40) Notably, this was not the case. Jobs were allocated to the heart of the city, not the inner city.

Labour recruitment developed the basis of this particular community. The number of Puerto Ricans living in New York City, as a whole was “88%, as 69% were living in East Harlem as of 1970.” (Cayo-Sexton, 22) Labour recruitment was the number one factor in creating this large community in East Harlem. Puerto Ricans helped others settle, find work, and build communities by relying on social networks containing friends and family. Puerto Rico became the site of one of the most massive emigration flows of this century. Puerto Rican migrants emigrated to the U.S. in search of higher-wage jobs. The Puerto Ricans found low-wage jobs in the latter years of the 1960s and 70s. The U.S. economy had a shift from the manufacturing sector to a service sector, forcing these people into hard times, as many of them worked in factories and relied on these particular jobs to support their families back home in Puerto Rico. The importance of factory jobs for a decent standard of living for these former rural workers proved crucial. “…labour in industrial production is still crucial and central to the global economy. However, the export of production from the center to the less media-visible periphery, and the development of the informational service economy, is an outright assault on working-class populations.” (Mencher, 23) Puerto Ricans were first desired for means of cheaper labour. The economy shifted away from a manufacturing unit, and had pursued cheaper labour elsewhere. The sole purpose of cheap labour was abandoned.

Puerto Rico remains a partially self-governing unincorporated territory of the United States, called a "commonwealth" (the same moniker used to name the body politic in one other territory, the Northern Mariana Islands, and four states, Kentucky, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Massachussetts) of the United States, with limited sovereignty. East Harlem is home to Puerto Ricans where evidence of abuse, hardship and poverty remain. The restructuring of the U.S. economy had significant impact on the Puerto Rican migrant finding work in New York specifically. This is often considered a displacement amongst Puerto Ricans on the island, and also the Nuyoricans. --Domenic.Demasi 14:25, 23 November 2007 (UTC)

Geography

Puerto Rico consists of a main island of Puerto Rico and various smaller islands, including Vieques, Culebra, Mona, Desecheo, and Caja de Muertos. Of the latter five, only Culebra and Vieques are inhabited year-round. Mona is uninhabited through large parts of the year except for employees of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural Resources. There are also many other even smaller islands including Monito and "La Isleta de San Juan", which includes Old San Juan and Puerta de Tierra.

Puerto Rico has an area of 5,324 sq mi (13,790 km²), and is slightly smaller than Connecticut. It is mostly mountainous with large coastal areas in the north and south regions of the island. The main mountainous range is called "La Cordillera Central" (The Central Range). The highest elevation point of Puerto Rico, Cerro de Punta (4,390 feet; 1,338 m),[22] is located in this range. Another important peak is El Yunque, one of the highest in the Sierra de Luquillo at the El Yunque National Forest, with a maximum elevation of 3,494 feet (1,065 m). The capital, San Juan, is located on the main island's north coast.

Located in the tropics, Puerto Rico enjoys an average temperature of 82.4 °F (28 °C) throughout the year. The seasons do not change very drastically. The temperature in the south is usually a few degrees higher than the north and temperatures in the central interior mountains are always cooler than the rest of the island. Hurricane season spans between June and November. The all-time low in Puerto Rico has been 40°F and in San Juan it has been 60°F.

Puerto Rico has 17 lakes, all of which are man-made reservoirs,[23] and more than 50 rivers, most born in the Cordillera Central. The rivers in the northern region of the island are typically larger and with higher water flow rates than those of the south region, given that the south receives less rain than the central and north regions.

As of 1998, 239 plants, sixteen birds and 39 amphibians/reptiles have been discovered that are endemic to the archipelago of Puerto Rico. The majority of these (234, 12 and 33 respectively) are found on the main island.[24] The most recognizable endemic species and a symbol of Puerto Rican pride is the Coquí, a small frog easily recognized by the sound from which it gets its name. The El Yunque National Forest in the north east, previously known as the Caribbean National Forest, a tropical rainforest is home to the majority (13 of 16) of species of coquí. It is also home to more than 240 plants, 26 of which are endemic and 50 bird species, including one of the top 10 endangered birds in the world, the Puerto Rican Amazon. The Guánica Dry Forest Reserve in the south west, 10,000 acres (40 km2) of dry land inhabited by over 600 uncommon types of plants and animals, including 48 endangered species and 16 that are endemic to Puerto Rico.

Geology

Puerto Rico is composed of Cretaceous to Eocene volcanic and plutonic rocks, which are overlain by younger Oligocene and more recent carbonates and other sedimentary rocks. Most of the caverns and karst topography on the island occurs in the northern region in the carbonates. The oldest rocks are approximately 190 million years old (Jurassic) and are located at Sierra Bermeja in the southwest part of the island. These rocks may represent part of the oceanic crust and are believed to come from the Pacific Ocean realm.

Puerto Rico lies at the boundary between the Caribbean and North American plates and is currently being deformed by the tectonic stresses caused by the interaction of these plates. These stresses may cause earthquakes and tsunamis. These seismic events, along with landslides, represent some of the most dangerous geologic hazards in the island and in the northeastern Caribbean. The most recent major earthquake occurred on October 11, 1918 and had an estimated magnitude of 7.5 on the Richter scale.[25] It originated off the coast of Aguadilla and was accompanied by a tsunami.

The Puerto Rico Trench, the largest and deepest trench in the Atlantic, is located about 75 miles (120 km) north of Puerto Rico in the Atlantic Ocean at the boundary between the Caribbean and North American plates.[26] The trench is 1,090 miles (1,754 km) long and about 60 miles (97 km) wide. At its deepest point, named the Milwaukee Deep, it is 27,493 feet (8,380 m) deep, or about 5.2 miles (8.38 km).[26]

Demographics

During the 1800s, hundreds of Corsican, French, Lebanese, Chinese, and Portuguese families, along with large numbers of immigrants from Spain (mainly from Catalonia, Asturias, Galicia, the Balearic Islands, Andalusia, and the Canary Islands) and numerous Spanish loyalists from Spain's former colonies in South America, arrived in Puerto Rico. Other settlers have included Irish, Scots, Germans, Italians, and thousands others who were granted land from Spain during the Real Cedula de Gracias de 1815 (Royal Decree of Graces of 1815), which allowed European Catholics to settle in the island with a certain amount of free land. This mass immigration during the 19th century helped the population grow from 155,000 in 1800 to almost a million at the close of the century. A census conducted by royal decree on September 30,1858, gives the following totals of the Puerto Rican population at this time, with 300,430 identified as Whites ; 341,015 as Free colored; and 41,736 as Slaves. More recently, Puerto Rico has become the permanent home of over 100,000 legal residents who immigrated from not only Spain, but from Latin America as well. Argentines, Cubans, Dominicans, Colombians and Venezuelans can also be counted as settlers.

Emigration has been a major part of Puerto Rico's recent history as well. Starting in the Post-WWII period, due to poverty, cheap airfare, and promotion by the island government, waves of Puerto Ricans moved to the continental United States, particularly to New York City, New York Newark, Jersey City, Paterson, and Camden, New Jersey; Chicago; Springfield and Boston, Massachusetts; Orlando, Miami and Tampa, Florida; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Hartford, Connecticut; Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, California. This continued even as Puerto Rico's economy improved and its birth rate declined. Emigration continues at the present time, and this, combined with Puerto Rico's greatly lowered birth rate, suggests that the island's population will age rapidly and start to decline sometime within the next couple of decades.

In the 2000 U.S. Census Puerto Ricans were asked to indicate in which racial categories they consider themselves to belong. The breakdown is as follows: 80% described themselves as "white"; 8% described themselves as "black"; 12% described themselves as "mulatto" and only 0.4% described themselves as "American Indian or Alaska Native" (the US Census does not consider Hispanic to be a race, and asks if a person considers himself Hispanic in a separate question).[27][28]

A recent study of Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from 800 individuals found 61.1% as having Amerindian maternal mtDNA, 26.4% as having African maternal mtDNA, and 12.5% as having Caucasian maternal mtDNA.[29] Conversely, patrilineal input, as indicated by the Y chromosome, showed that 70% of all Puerto Rican males have inherited Y chromosome DNA from a male European ancestor, 20% have inherited Y chromosome DNA from a male African ancestor, and fewer than 10% have inherited Y chromosome DNA from a male Amerindian ancestor. In summary, the results suggest that the three largest components of the Puerto Rican genetic pool are European/Caucasian, Amerindian, and African, in descending order.

Languages

The official languages of the island are Spanish and English. Spanish is the primary language of Puerto Ricans, though English is taught as a second language in public and private schools from elementary levels to high school. [30] The Spanish of Puerto Rico is well known for some interesting linguistic features.

In 1991, Governor Rafael Hernández Colón signed a law declaring Spanish as the sole official language of the island's government. While some applauded the governor's decision (mainly members of the political parties supporting commonwealth-status and independence), others opposed it, including statehood supporters, who saw it as another attempt to move the islands away from eventual statehood. As a result of his actions, the People of Puerto Rico won the Literature's Prince of Asturias Award in 1991, which is awarded annually to those who defend and contribute to the growth of the Spanish language.[31] Upon his election as governor in 1993, pro-statehood former Governor Pedro Rosselló overturned the law enacted by his predecessor and once again established both English and Spanish as official languages. This move by the pro-statehood governor was seen by many as another attempt to move the island closer to statehood. However, despite two locally-authorized plebiscites, statehood never came about during his two consecutive terms.

Religion

The Roman Catholic Church has been historically the most dominant religion of the majority of Puerto Ricans, although the presence of various Protestant denominations has increased under American sovereignty, making modern Puerto Rico an interconfessional country. Protestantism was suppressed under the Spanish regime, but encouraged under American rule of the island.

Taíno religious practices have to a degree been rediscovered/reinvented by a handful of advocates. Various African religious practices have been present since the arrival of enslaved Africans. In particular, the Yoruba beliefs of Santeria and/or Ifá, and the Kongo derived Palo Mayombe (sometimes called an African belief system, but rather a way of Bantu lifestyle of Congo origin) find adherence among very few individuals who practice some form of African traditional religion.

Politics

Government of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico's head of state is the President of the United States. The government of Puerto Rico is based on the formal republican system composed of three branches: the Executive branch headed by the Governor, currently Anibal Acevedo Vila, the Legislative branch consisting of a bicameral Legislative Assembly (a Senate and a House of Representatives), headed by the President of the Senate, currently Kenneth McClintock and the House Speaker, currently Jóse Aponte Hernandez, and the Judicial branch, headed by the Chief Justice of the Puerto Rico Supreme Court, currently Federico Hernandez Denton, that form the formal government. The legal system is based on a mix of the civil law and the common law systems. The governor as well as legislators are elected by popular vote every four years. Members of the Judicial branch are appointed by the governor with the "advice and consent" of the Senate.

Puerto Rico has limited representation in the U.S. Congress in the form of a Resident Commissioner, currently Luis Fortuño, a nonvoting delegate, and the current Congress had returned the Commissioner's power to vote in the Committee of the Whole, but not on matters where the vote would represent a decisive participation.[32] Because no federal elections are held in any of the unincorporated territories, Puerto Rico does not have electors in the U.S. Electoral College.

Administrative divisions

As an unincorporated territory of the United States, Puerto Rico does not have any first-order administrative divisions as defined by the U.S. Government, but there are 78 municipalities at the second level (Mona Island is not a municipality, but part of the municipality of Mayagüez).[1] Municipalities are subdivided into wards or barrios, and those into sectors. Each municipality has a mayor and a municipal legislature elected for a 4 year term.

The first municipality (previously called "town") of Puerto Rico, San Juan, was founded in 1521, now considered the United States' oldest city, older by several decades than St. Augustine, Florida. In the 16th century two more municipalities were established, San Germán (1570), and Coamo (1579). Three more municipalities were established in the 17th century. These were Arecibo (1614), Aguada (1692) and Ponce (1692). The 18th and 19th century saw an increase in settlement in Puerto Rico. 30 municipalities were established in the 18th century and 34 more were established in the 19th century. Only six municipalities were founded in the 20th century. The last municipality was Florida, founded in 1971.[33]

Political history

In 1950, the U.S. Congress gave Puerto Ricans the right to organize a constitutional convention, contingent on the results of a referendum, where the electorate would determine if they wished to organize their own government pursuant to a constitution of their own choosing. Puerto Ricans expressed their support for this measure in a 1951 referendum, which gave voters a yes-or-no choice for the commonwealth status, defined as a 'permanent association with a federal union' but which did not offer independence or statehood as ballot options. A second referendum was held to ratify the constitution, which was adopted in 1952.

Prior to approving the new constitution, the Constitutional Convention specified the name by which the body politic would be known. On February 4 1952, the convention approved Resolution 22 which chose in English the word “Commonwealth ”, meaning a “politically organized community” or “state,” which is simultaneously connected by a compact or treaty to another political system. The convention adopted a translation into Spanish of the term, inspired by the Irish saorstát (Free State) of “Estado Libre Asociado” (ELA) to represent the relationship adopted "in the manner of a compact" between the people of Puerto Rico and the United States. Literally translated into English, the phrase means “Associated Free State.”

In 1967, the Legislative Assembly tested political interests of the Puerto Rican people by passing a plebiscite Act that allowed a vote on the status of Puerto Rico. This constituted the first plebiscite by the Legislature for a choice on three status options. Puerto Rican leaders had lobbied for such an opportunity repeatedly, in 1898, 1912, 1914, 1919, 1923, 1929, 1932, 1939, 1943, 1944, 1948, 1956, and 1960. The Commonwealth option, represented by the PDP, won with an overwhelming majority of 60.4 percent of the votes. The Statehood Republican Party, as well as the Puerto Rico Independence Party boycotted the vote.

Following the plebiscite, efforts in the 1970s to enact legislation to address the status issue died in Congressional committees. In the 1993 plebiscite, in which Congress played a more substantial role, Commonwealth status was again upheld.[34] In the 1998 plebiscite, all the options were rejected when an absolute majority of the voters (50.3%) voted in favor of the "none of the above" option, again favoring the commonwealth status quo by default. [35]

International status

On November 27, 1953, shortly after the establishment of the Commonwealth, the General Assembly of the UN approved Resolution 748, removing Puerto Rico’s classification as a non-self-governing territory under article 73(e) of the Charter from United Nations. However, the UN General Assembly did not apply its full list of criteria to Puerto Rico for determining whether or not self-governing status had been achieved. In fact, in a 1996 report on a Puerto Rico status political bill, the U.S. Committee on Resources stated that Puerto Rico’s current status “does not meet the criteria for any of the options for full self-government.” The House Committee concluded that Puerto Rico is still an unincorporated territory of the United States under the territorial clause, that the establishment of local self-government with the consent of the people can be unilaterally revoked by the U.S. Congress, and that U.S. Congress can also withdraw the U.S. citizenship presently enjoyed by the residents of Puerto Rico at any time, as long as it achieves a legitimate Federal purpose. [36] The application of the Constitution to Puerto Rico is limited by the Insular Cases.

Even though Puerto Rico, as a territory of the United States, has no established embassies,not unlike other "gateway" states, it hosts Consulates from 42 countries, mainly from the Western Hemisphere and Europe. Most consulates are located in San Juan, capital of Puerto Rico. Although Papal Nuncios serve a dual diplomatic and ecclesiastical role, since the United States established diplomatic relations with the Vatican State in 1982, although the Papal Nuncio in Washington, DC, exercises diplomatic jurisdiction over Puerto Rico as a United States territory, the Papal Nuncio based in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic excercises ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the islands of Puerto Rico.

Political status within the United States

Under its 1952 constitution, the people of Puerto Rico describe themselves as a Commonwealth and enjoys a significant degree of administrative-autonomy similar to that of a state of the Union. Puerto Ricans are statutory U.S. Citizens but, because Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory and not a U.S. state, the U.S. Constitution does not enfranchise U.S. citizens residing in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico does participate in the internal political process of both the Democratic and Republican Parties in the United States, accorded equal-proportional representation in both parties with full state-like complements of 22 Republican delegates and 60 Democratic delegates with full voting representation in each party's national convention.

Puerto Rico is classified by the U.S. government as an independent taxation authority under the the U.S. Internal Revenue Code (IRC). A common misconception is that residents of Puerto Rico do not have to pay federal taxes. Residents of the island do pay many federal taxes (import/export taxes, federal commodity taxes, social security taxes, etc.) and some even pay federal income taxes (Puerto Rico residents who are federal employees, or who do business with the federal government, Puerto Rico-based corporations that intend to send funds to the U.S., etc). While most residents of the island do not pay federal income tax, they do pay federal payroll taxes (Social Security and Medicare), as well as Puerto Rico income taxes, the highest state-level income taxes imposed in the nation. In addition, because the trigger point for income taxation is lower than that of the IRC, and because the per-capita income in Puerto Rico is much lower than the average per-capita income in the rest of the nation, more Puerto Rico residents pay income taxes to the local taxation authority than they would pay federal income taxes if the IRC were fully applied to the island. Puerto Rico residents are eligible for Social Security retirement, survivor and disability benefits. Puerto Rico is excluded from the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program and islands' residents do not qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Puerto Rico receives less than 15% of the Medicaid funding it would be allotted as a state, and although fully taxed by Medicare, is alloted only about 75% of state-level benefits.

As statutory U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans may enlist in the U.S. military. Puerto Ricans have been subject to the military draft, when it has been in effect. Puerto Ricans have fully participated in all U.S. wars since 1898, most notably in World War II, in the Korean and Vietnam wars, and the current Middle-Eastern conflicts.

Recent developments on status

According to a December 2005 report by the President’s Task Force on Puerto Rico’s Status, it is not possible “to bind future (U.S.) Congresses to any particular arrangement for Puerto Rico as a Commonwealth”. This determination was based on articles in the U.S. Constitution regarding territories. Prominent leaders in the pro-statehood and pro-independence political movements agree with this assessment. The Popular Democratic Party (PPD) announced a commitment to challenge the task force's report and validate the current status in all international forums including the United Nations. It also rejects any colonial or territorial status as a status option, and vows to keep working for the enhanced Commonwealth status that was approved by the PPD in 1998 which included sovereignty, an association based on "respect and dignity between both nations", and common citizenship. [37]

The Legislative Branch, controlled by the opposing New Progressive Party (PNP), supported the White House Report's conclusions and has supported bills introduced by Reps. Jose Serrano (D-NY) and Luis Fortuño (R-PR) and Sens. Ken Salazar (D-CO) and Mel Martinez (R-FL) to provide for a democratic referendum process among Puerto Rico voters.

Political parties

As an unincorporated territory of the U.S. since 1898, the ideology of Puerto Ricans is represented by three of its four registered political parties, which stand for three distinct future political scenarios that are non-conformist regarding Puerto Rico's territorial or colonial status: (1) those who favor an autonomous, sovereign bilateral relationship with the United States (so-called "improved"/"enhanced" U.S. Commonwealth outside the U.S. Constitution's "Territorial Clause" or Free Associated Republic status); (2) those that favor that Puerto Rico's national independence should be recognized by the United States, as a full-fledged sovereign republic within the concert of the international community at-large; and, (3) those who favor Puerto Rico's entry into the U.S. as a full-fledged state of the federated union, by becoming the 51st state.

The Popular Democratic Party (PPD) seeks to maintain the island's "association" status as a commonwealth, improved commonwealth and/or seek a true free sovereign-association status or Free Associated Republic, and has won a plurality vote in referendums on the island's status held over six decades after the island was invaded by the United States (that said, most referendums' fairness have been impugned by one or two of the opposition parties).

The New Progressive Party (PNP) seeks statehood for Puerto Rico.

The Puerto Rican Independence Party and the Nationalist Party both seek independence for the nation of Puerto Rico, albeit through different means. The Nationalist Party, for example, does not participate in elections held every four years. Although they maintain close relations and are considered allies within an otherwise rather divided Puerto Rican Independence Movement, the Puerto Rican Independence Party, on the other hand, does participate in gubernatorial elections held every four years since 1948.

A recently-registered "Puerto Ricans for Puerto Rico Party" (PPR) does not espouse a particular political status option.

Economy

In the early 1900s the greatest contributor to Puerto Rico's economy was agriculture, its main crop being sugar. In the late 1940s a series of projects codenamed Operation Bootstrap encouraged, using tax exemptions, the establishment of factories. Thus manufacturing replaced agriculture as the main industry. Puerto Rico is currently classified as a high income country by the World Bank. [38] [39]

The economic conditions in Puerto Rico have improved dramatically since the Great Depression due to external investment in capital-intensive industry such as petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and technology. Once the beneficiary of special tax treatment from the U.S. government, today local industries must compete with those in more economically depressed parts of the world where wages are not subject to U.S. minimum wage legislation. In recent years, some U.S. and foreign owned factories have moved to lower wage countries in Latin America and Asia. Puerto Rico is subject to U.S. trade laws and restrictions.

Tourism is a component of the Puerto Rican economy supplying an approximate $1.8 billion, or 6% of the islands' economic activity. In 1999, an estimated 5 million tourists visited the island, most from the United States. Nearly a third of these are cruise ship passengers. A steady increase in hotel registrations, which had been observed since 1998, has been counter-balanced by the closings of important hotels, such as the Dorado Beach and Cerromar Hotels, the chronic delay in opening the Cayo Largo Hotel and the cancellation of two major resort complexes in the northeast Atlantic coast. In spite of the construction of a few new smaller hotels and new tourism projects, such as the Puerto Rico Convention Center, the tourism industry's growth has remained relatively stagnant. The reopening of the La Concha/Condado Beach complex and the building of the convention center's adjoining hotels may help spur new growth in the tourism sector of the economy.

Puerto Ricans had a per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) estimate of $22,058 for 2006,[1] which demonstrates a growth over the $14,412 level measured in the 2002 Current Population Survey by the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund.[40] In that survey, Puerto Ricans had a 48.2% poverty rate. By comparison, the poorest State of the Union, Mississippi, had a median level of $21,587, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey, 2002 to 2004 Annual Social and Economic Supplements.[41] Since 1952, the gap between Puerto Rico's per capita income and U.S. national levels has essentially remained unchanged — one third the U.S. national average and roughly half that of the poorest state. The United Nation's Human Development Index ranking is not regularly available for Puerto Rico, though the UN Development Program assigned it a .942 score in 1998, which would place it among the top 15 countries in the HDI rankings. [42]

On May 1, 2006, the Puerto Rican government faced significant shortages in cash flows, which led the Governor to close the local Department of Education and 42 other government agencies. All 1,536 public schools closed, and 95,762 people were furloughed in the first-ever partial shutdown of the government in the island's history.[43] On May 10, 2006, the budget crisis was resolved with a new tax reform agreement, with plans to apply a temporary 1% tax input so that all government employees could return to work. On November 15, 2006 a 5.5% sales tax was implemented. Municipalities initially had the option of applying a municipal sales tax of 1.5% bringing the total sales tax to 7%.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

Although boxing, basketball, and volleyball are popular, traditionally baseball is the most popular sport. Puerto Rico has its own professional baseball league which operates as a winter league. No major league franchise or affiliate plays in Puerto Rico; however, San Juan hosted the Montreal Expos for several series in 2003 and 2004 before they moved to Washington, D.C. and became the Washington Nationals. Puerto Rico has participated in the World Cup of Baseball winning 1 gold (1951), 4 silver and 4 bronze medals. Famous Puerto Rican baseball players include Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda, enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973 and 1999, respectively.[44][45] Famous Puerto Rican boxers include Felix Trinidad, Miguel Cotto, Wilfredo Benitez, and Wilfredo Gomez . Puerto Rico, despite being a small island, has had more World boxing champions than any other country, besides the United States. See: list of Boxing world champions.

Juan "Pachín" Vicens, was one of Puerto Rico's most distinguished amateur basketball players, becoming the first Puerto Rican to receive the distinction of becoming the world's most distinguished player in a team sport, when he was named "Best Basketball Player in the World" in the 1959 World Championship in Chile.[46] Basketball players that played in the National Basketball Association include Ramon Rivas, Ramon Ramos Carlos Arroyo, Jose Juan Barea and José Ortiz.

August 8, 2004, became a landmark date for Puerto Rico's national Olympic team when the basketball team of Puerto Rico defeated the U.S. basketball team in Athens, Greece, the defending gold medalist and basketball powerhouse in Olympic play.[47] On September 29, 2005, Major League Baseball (MLB) announced that San Juan's Hiram Bithorn Stadium would be one of the sites of the opening round as well as the second round of the newly formed World Baseball Classic, a 16-country tournament featuring top players, which was held in San Juan in March 2006. Puerto Rico fielded its own team in that event, composed mostly of MLB players, which survived the opening round but was eliminated in the second round.

Professional wrestling has enjoyed much popularity in Puerto Rico for a long time. Matches have been televised since the 1960s, and multiple, non-televised matches are held each week across the island. The World Wrestling Council is the main wrestling promoter in Puerto Rico. Famous Puerto Rican wrestlers have included Barrabas, Carlos Colon and his son, Carlito, Los Invaders, Savio Vega, Pedro Morales, and Los Super Médicos. Many World Wrestling Entertainment stars, such as Randy Savage and Ric Flair have fought in Puerto Rico. Women's wrestling has been gaining popularity in Puerto Rico since the 1990s.

The Puerto Rico Islanders soccer team, founded in 2003, plays in the United Soccer Leagues First Division, which constitutes the second tier of soccer in North America. Puerto Rico is also a member of FIFA and Concacaf but the national team has so far failed to qualify for the World Cup final tournament.

Road running is a very popular sport and recreative activity across the island. Almost each weekend several road running events are held across the island. The most successful Puerto Rican road runner is Jorge "Peco" Gonzalez, who won several gold medals at the Central American and Caribbean Games and Pan American Games.

Transportation

Land Transportation

Puerto Rico is connected by a system of freeways, expressways, and highways, all maintained by the Highways and Transportation Authority and patrolled by the Police of Puerto Rico. The island's metropolitan area is served by a public bus transit system and a underutilizedmetro system called Tren Urbano (in English: Urban Train). Other forms of public transportation include sea-borne ferries (that serve Puerto Rico's archipelago, composed of various substantially-populated islands) as well as “Carros Públicos” (Mini Bus), similar to jitney service on the United States. The island's main airport, Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport, is located in Carolina, and serves the rest of the island as well as the Virgin Islands. The most recently renovated airport in the west of Puerto Rico is that of the former Ramey Military airbase in Aguadilla, Rafael Hernandez Airport, which has made it easier to explore the towns of the newly renamed tourism area known as "Porta del Sol." The main port of the island is San Juan Port, although a major transshipment port is being developed in Ponce.

Ocean Transportation

In what regards water-based transportation of any merchandise or persons shipped entirely or even partly by water between U.S. points—either directly or indirectly via one or any number of foreign points—U.S. Federal Law requires that said items or persons must travel in U.S.-built, U.S.-crewed, U.S.-citizen owned vessels that are U.S.-documented by the Coast Guard for such maritime “cabotage” carriage. This transportation/trade restriction is imposed on Puerto Rico per the Jones Act of 1920 (Merchant Marine Act of 1920). The Jones Act and various other United States laws that govern the domestic and domestic-foreign-domestic transportation of merchandise and passengers by water between two points in the United States have been extended to that island-territory since the initial years of United States’ claim over the sovereignty of the island.

Strictly construed, the Jones Act refers only to Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (46 U.S.C. 883; 19 CFR 4.80 and 4.80(b)), which has come to bear the name of its original sponsor, Sen. Wesley L. Jones. Another law that was enacted in 1886 requires essentially the same standards for the transport of passengers between U.S. points, directly or indirectly transported through foreign ports or foreign points (46 App. U.S.C. 289; 19 CFR 4.80(a)). However, since the mid-1980s, as part of a joint effort between the cruise-ship industry that serves Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican politicians such as then Resident Commissioner, U.S. non-voting Representative Baltasar Corrada del Río, obtained a limited-exception since no U.S. cruise ships that were Jones Act-eligible were participating in said market.

The application of these coastwise shipping laws and their imposition on Puerto Rico consist in a serious restriction of free trade and have been under scrutiny and controversy due to the apparent contradictory rhetoric involving the United States Government's sponsorship of free trade policies around the world, while its own national shipping policy (Cabotage Law) is essentially mercantilist and based on notions foreign to free-trade principles.

See also

References

- ^ a b c [1].

- ^ Organigrama del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (in Spanish), Government of Puerto Rico - Puerto Rico

- ^ Keith Bea (May 25, 2005). "Political Status of Puerto Rico: Background, Options, and Issues in the 109th Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Special committee on decolonization approves text calling on United States to expedite Puerto Rican self-determination process" (Press release). Department of Public Information, United Nations General Assembly. 13 June, 2006. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite press release}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cite error: The named reference

statuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Iñigo Abbad y Lasierra. Historia Geográfica, Civil y Natural de la Isla de San Juan Bautista de Puerto Rico.

- ^ Vieques Island - What lies beneath.

- ^ Brief Chronology of Puerto Rico.

- ^ Presently, Puerto Ricans are also known as Boricuas, or people from Borinquen.

- ^ Vicente Yáñez Pinzón was the first appointed governor but he never arrived on the island.

- ^ USA Seizes Puerto Rico

- ^ "History". topuertorico.org. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ Chronology of Puerto Rico in the Spanish-American War

- ^ Treaty of Paris (1898)

- ^ García, Marvin. "Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos". National-Louis University. Retrieved April 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Latino/a Education Network Service, retrieved 5 February 2007

- ^ Anglelo Falcón, "Atlas of Stateside Puerto Ricans", Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, published 6 December 2004, retrieved 5 February 2007

- ^ Act of July 3, 1950, Ch. 446, 64 Stat. 319.

- ^ Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico - in Spanish (Spanish).

- ^ Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico - in English (English translation).

- ^ "Ciudadanía de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Departamento de Estado, Estado del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. 29 April 2005. Retrieved November 9.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|year=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Los Lagos de Puerto Rico Template:Es icon

- ^ Island Directory.

- ^ "Earthquake History of Puerto Rico". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ a b Uri ten Brink. "Explorations: Puerto Rico Trench 2003 - Cruise Summary and Results". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ "Puerto Rico". The Dispatch Online. 25 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Puerto Rico DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000.

- ^ Martínez Cruzado, Juan C. (2002). The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean:Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic. KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology [On-line Journal], Special Issue, Lynne Guitar, Ed. Available at: http://www.kacike.org/MartinezEnglish.pdf [Date of access: 25 September, 2006]

- ^ Description of Puerto Rico by Topuertorico.org.

- ^ Fundación Príncipe de Asturias

- ^ Rules of the House of Representatives

- ^ LinktoPR.com - Fundación de los Pueblos.

- ^ For the complete statistics regarding these plebiscites please refer to Elections in Puerto Rico:Results.

- ^ "Elections in Puerto Rico: 1998 Status Plebiscite Vote Summary". electionspuertorico.org. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Status Field Hearing". Committee on Resources, U.S. House of Representatives, 105th Congress. April 19, 1997. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Independence Hearing by the Puerto Rico Herald.

- ^ Data and Statistics of Country Groups of the World Bank

- ^ Income report for Puerto Rico by the World Bank.

- ^ PRLDEF.

- ^ U.S. Census - Median Family Income.

- ^ "Puerto Rico (United States)". islands.unep.ch. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ Rodríguez, Magdalys. "No hubo acuerdo y el gobierno amaneció cerrado". El Nuevo Día. Retrieved 2006-05-01.Template:Es icon

- ^ Baseball Hall of Fame entry for Roberto Clemente accessed on September 30, 2007

- ^ Baseball Hall of Fame entry for Orlando Cepeda accessed on September 30, 2007

- ^ Gems, Gerald R. (2006). The Athletic Crusade: Sport And American Cultural Imperialism. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803222165.

- ^ BBC Sports - Olympics 2004.

References for Puerto Rican Migration to the United States

- Grosfoguel, Ramón (2003). Colonial Subjects: Puerto Ricans in a Global Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Heine, Jorge (ed.) (1983). Time for Decision: The United States and Puerto Rico (Lanham, MD: The North-South Publishing Co.).

- Jennings, James, and Monte Rivera (eds) (1984). Puerto Rican Politics in Urban America (Westport: Greewood Press).

- Moreno Vega, Marta (2004). When the Spirits Dance Mambo: Growing Up Nuyorican in El Barrio (New York: Three Rivers Press).

- Cayo-Sexton, Patricia. 1965. Spanish Harlem: An Anatomy of Poverty. New York: Harper and Row.

- Davila, Arlene. Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos and the Neoliberal City. University of California Press. 2004.

- Mencher, Joan. 1989. Growing Up in Eastville, a Barrio of New York. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Padilla, Elena. 1992. Up From Puerto Rico. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Salas, Leonardo. "From San Juan to New York: The History of the Puerto Rican". America: History and Life. 31 (1990).

- Bourgois, Philippe. 2003. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio.

Further reading

- Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny. Addison-Wesley Publishing. ISBN 0-201-52396-5.

- Burnett, Christina Duffy and Marshall, Burke, Foreign in a Domestic Sense, Duke University Press, 2001.

== External links ==

Puerto Rican government

Country profiles

Directories, news and travel

- PRWow! portal, including directories, news, and information on Puerto Rico

- Official Puerto Rico travel and tourism site

- Template:Wikitravel

United Nations (U.N.) Declaration on Puerto Rico

Photos

- Directory of websites with photo galleries of Puerto Rico

- Site dedicated exclusively to photos of Puerto Rico

- Collection of color photos of Puerto Rico in the 1940s and 1950s

Template:West Indies

Template:Countries and territories of Middle America

![]() United States

United States