Ernest Hemingway: Difference between revisions

→In popular culture: Completely wrong information. Here's To Life is about various people who influenced the singers' life, not completely about Hemingway. |

|||

| Line 251: | Line 251: | ||

*Hemingway's downfall was namelessly described in [[Rush (band)|Rush]]'s 1982 song, "Losing It", which told the tales of a couple of different people, a dancer and a writer, who could no longer perform their professions due to age, health, or other reasons. |

*Hemingway's downfall was namelessly described in [[Rush (band)|Rush]]'s 1982 song, "Losing It", which told the tales of a couple of different people, a dancer and a writer, who could no longer perform their professions due to age, health, or other reasons. |

||

*The [[Streetlight Manifesto]] song 'Here's to Life' is |

*The [[Streetlight Manifesto]] song 'Here's to Life' is a tribute to various authors and musicians whose actions had influenced [[Tomas Kalnoky]]'s life. Hemingway is one of the few people mentioned. |

||

==Anecdotes== |

==Anecdotes== |

||

Revision as of 21:18, 4 January 2008

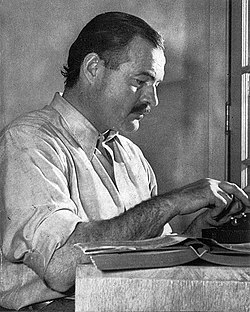

Hemingway in 1939 | |

| Born | July 21, 1899 Oak Park, Illinois |

| Died | July 2, 1961 (aged 61) Ketchum, Idaho |

| Occupation | Writer and journalist |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Lost Generation |

| Literary movement | The Lost Generation Nobel Prize in Literature (1954) |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1921-1927) Pauline Pfeiffer (1927-1940) Martha Gellhorn (1940-1945) Mary Welsh Hemingway (1946-1961) |

| Children | Jack Hemingway (1923-2000) Patrick Hemingway (1928-) Gregory Hemingway (1931-2001) |

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. Nicknaming himself "Papa" while still in his 20s, he was part of the 1920s expatriate community in Paris known as "the Lost Generation", as described in his memoir A Moveable Feast. He led a turbulent social life (married four times and allegedly had multiple extra-marital relationships over many years[citation needed]). Hemingway received the Pulitzer Prize in 1953 for The Old Man and the Sea. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. During his later life, Hemingway suffered from increasing physical and mental problems. In July 1961, after being released from a mental hospital where he'd been treated for severe depression[citation needed], he committed suicide at his home in Ketchum, Idaho with a shotgun.

Hemingway's distinctive writing style is characterized by economy and understatement, in contrast to the style of his literary rival William Faulkner. It had a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century fiction writing. His protagonists are typically stoic males who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure." Many of his works are now considered canonical in American literature.

Biography

Early life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. Hemingway was the third son and the second child born to Clarence Edmonds "Doctor Ed" Hemingway, a country doctor, and Grace Hall Hemingway. Hemingway's father attended the birth of Ernest and blew a horn on his front porch to announce to the neighbors that his wife had given birth to a boy. The Hemingways lived in a six-bedroom Victorian house built by Ernest's widowed maternal grandfather, Ernest Hall, an English immigrant and Civil War veteran who lived with the family. Hemingway was his namesake.

Hemingway's mother once aspired to an opera career and earned money giving voice and music lessons. She was domineering and narrowly religious, mirroring the strict Protestant ethic of Oak Park, which Hemingway later said had "wide lawns and narrow minds".[1] His mother had wanted twins, and when this did not happen, she dressed young Ernest and his sister Marcelline (eighteen months older) in similar clothes and with similar hairstyles, maintaining the pretense of the two children being "twins." Some biographers have suggested that Grace Hemingway further "feminised" her son in his youth by calling him "Ernestine", but male infants and toddlers of the Victorian middle-class were often dressed as females.[2] Many themes in Hemingway's work point to destructive interactions between male and female sexual partners (cf. "Hills Like White Elephants"), within marital unions (cf. Now I Lay Me, The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber), and among most other combinations of men and women (cf. The Sun Also Rises); in addition certain posthumously published pieces contain ambiguous treatment of gender roles. However, no connection between Hemingway's depiction of these human conditions and his own early childhood experiences has been established.

While his mother hoped that her son would develop an interest in music, Hemingway adopted his father's outdoorsman hobbies of hunting, fishing and camping in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. The family owned a house called Windemere on Michigan's Walloon Lake and often spent summers vacationing there. These early experiences in close contact with nature instilled in Hemingway a lifelong passion for outdoor adventure and for living in remote or isolated areas.

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School from September, 1913 until graduation in June 1917. He excelled both academically and athletically; he boxed, played football, and displayed particular talent in English classes. His first writing experience was writing for "Trapeze" and "Tabula" (the school's newspaper and yearbook, respectively) in his junior year, then serving as editor in his senior year. He sometimes wrote under the pen name Ring Lardner, Jr., a nod to his literary hero Ring Lardner.[3]

After high school, Hemingway did not want to go to college. Instead, at age eighteen, he began his writing career as a cub reporter for The Kansas City Star. Although he worked at the newspaper for only six months (October 17, 1917-April 30, 1918), throughout his lifetime he used the guidance of the Star's style guide as a foundation for his writing style: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."[4] In honor of the centennial year of Hemingway's birth (1899), The Star named Hemingway its top reporter of the last hundred years.

Hemingway left his reporting job after only a few months and, against his father's wishes, tried to join the United States Army to see action in World War I. He failed the medical examination due to poor vision, and instead joined the Red Cross Ambulance Corps. On his route to the Italian front, he stopped in Paris, which was under constant bombardment from German artillery. Instead of staying in the relative safety of the Hotel Florida, Hemingway tried to get as close to combat as possible.

Soon after arriving on the Italian Front Hemingway witnessed the brutalities of war. On his first day on duty, an ammunition factory near Milan blew up. Hemingway had to pick up the human, primarily female, remains. This first encounter with death left him shaken.

The soldiers he met later did not lighten the horror. One of them, Eric Dorman-Smith, entertained Hemingway with a line from Part Two of Shakespeare's Henry IV: "By my troth, I care not; a man can die but once; we owe God a death...and let it go which way it will, he that dies this year is quit for the next."[5] (Hemingway, for his part, would quote this line in The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber, one of his famous short stories set in Africa.) To another soldier, Hemingway once said, "You are troppo vecchio (It. too old) for this war, pop." The 50-year old soldier replied, "I can die as well as any man."[6]

On 8 July 1918, Hemingway was wounded delivering supplies to soldiers, which ended his career as an ambulance driver. He was hit by an Austrian trench mortar shell that left fragments in his legs, and was also hit by a burst of machine-gun fire. He was later awarded the Silver Medal of Military Valor (medaglia d'argento) from the Italian government for dragging a wounded Italian soldier to safety in spite of his own injuries.

Hemingway worked in a Milan hospital run by the American Red Cross. With very little in the way of entertainment, he often drank heavily and read newspapers to pass the time. Here he met Agnes von Kurowsky of Washington, D.C., one of eighteen nurses attending groups of four patients each. She was more than six years older than he. Hemingway fell in love with her, but their relationship did not survive his return to the United States; instead of following Hemingway to America, as originally planned, she became romantically involved with an Italian officer. This left an indelible mark on his psyche and provided inspiration for, and was fictionalized in, one of his early novels, A Farewell to Arms. Later in life, Hemingway identified even more closely with the protagonist of that novel, claiming (falsely) to have attained the rank of Lieutenant in the Italian Army and to have fought in three battles.

First novels and other early works

After the war, Hemingway returned to Oak Park. Driven from the United States in part due to prohibition, in 1920, he moved to an apartment on 1599 Bathurst Street, now known as The Hemingway, in the Humewood-Cedarvale neighborhood in Toronto, Ontario.[7] During his stay, he found a job with the Toronto Star newspaper. He worked as a freelancer, staff writer, and foreign correspondent. Hemingway befriended fellow Star reporter Morley Callaghan. Callaghan had begun writing short stories at this time; he showed them to Hemingway, who praised them as fine work. They would later be reunited in Paris.

For a short time from late 1920 through most of 1921, Hemingway lived on the near north side of Chicago, while still filing stories for The Toronto Star. He also worked as associate editor of the Co-operative Commonwealth, a monthly journal. In 1921, Hemingway married his first wife, Hadley Richardson. After the honeymoon they moved to a cramped top floor apartment on the 1300 block of Clark Street.[8] In September, he moved to a cramped fourth floor apartment (3rd floor by Chicago building standard) at 1239 North Dearborn in a then run-down section of Chicago's near north side. The building still stands with a plaque on the front of it calling it "The Hemingway Apartment." Hadley found it dark and depressing, but in December, 1921, the Hemingways left Chicago and Oak Park, never to live there again, and moved abroad.

At the advice of Sherwood Anderson, they settled in Paris, France, where Hemingway covered the Greco-Turkish War for the Toronto Star. After Hemingway's return to Paris, Anderson gave him a letter of introduction to Gertrude Stein. She became his mentor and introduced him to the "Parisian Modern Movement" then ongoing in the Montparnasse Quarter; this was the beginning of the American expatriate circle that became known as the "Lost Generation", a term popularized by Hemingway in the epigraph to his novel, The Sun Also Rises, and his memoir, A Moveable Feast. The epithet, "Lost Generation" was reportedly appropriated by Miss Stein from her French garage mechanic when he made the offhand comment that hers was "une generation perdue". His other influential mentor was Ezra Pound,[9] the founder of imagism. Hemingway later said of this eclectic group, "Ezra was right half the time, and when he was wrong, he was so wrong you were never in any doubt about it. Gertrude was always right."[10] The group often frequented Sylvia Beach's bookshop, Shakespeare & Co., at 12 Rue de l'Odéon. After the 1922 publication and American banning of colleague James Joyce's Ulysses, Hemingway used Toronto-based friends to smuggle copies of the novel into the United States (Hemingway writes of meeting and talking with Joyce in Paris in A Moveable Feast). His own first book, called Three Stories and Ten Poems (1923), was published in Paris by Robert McAlmon.

After much success as a foreign correspondent, Hemingway returned to Toronto in 1923. During his second stint living in Toronto, Hemingway's first son was born. He was named John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway, but would later be known as Jack. Hemingway asked Gertrude Stein to be Jack's godmother.

Around the same time, Hemingway had a bitter falling out with his editor, Harry Hindmarsh, who believed Hemingway had been spoiled by his time overseas.[11] Hindmarsh gave Hemingway mundane assignments, and Hemingway grew bitter and wrote an angry resignation in December of 1923. However, his resignation was either ignored or rescinded, and Hemingway continued to write sporadically for The Toronto Star through 1924.[12] Most of Hemingway's work for the Star was later published in the 1985 collection Dateline: Toronto.

Hemingway's American literary debut came with the publication of the short story cycle In Our Time (1925). The vignettes that now constitute the interchapters of the American version were initially published in Europe as in our time (1924). This work was important for Hemingway, reaffirming to him that his minimalist style could be accepted by the literary community. "Big Two-Hearted River" is the collection's best-known story.

In April 1925, two weeks after the publication of The Great Gatsby, Hemingway met F. Scott Fitzgerald at the Dingo Bar. Fitzgerald and Hemingway were at first close friends, often drinking and talking together. They frequently exchanged manuscripts, and Fitzgerald tried to do much to advance Hemingway's career and the publication of his first collections of stories, although the relationship later cooled and became more competitive. Fitzgerald's wife Zelda, however, disliked Hemingway from the start. Openly describing him as "bogus" and "phoney as a rubber cheque" and asserting that his macho persona was a facade, she became "convinced" that Ernest was homosexual and accused her husband of having an affair with him.

Some sources have speculated that Hemingway's well-documented homophobia and his frequent attacks on openly gay individuals, such as Jean Cocteau, was overcompensation for latent homosexuality. In one such instance, an anecdote told by Hemingway has an enraged Cocteau charging Radiguet (known in the Parisian literary circles as "Monsieur Bébé") with decadence for his tryst with a model: "Bébé est vicieuse. Il aime les femmes." ("Baby is depraved. He likes women." [Note the use of the feminine adjective]). Radiguet, Hemingway implies, employed his sexuality to advance his career, being a writer "who knew how to make his career not only with his pen but with his pencil", a salacious, phallic allusion.[13][14] The proposed argument is that the rage against Cocteau and Radiguet (whose relationship has been heavily contested in other sources) shows an inherent hostility against homosexuals and that this hostility can be traced in some of his short fiction, including "The Sea Change".[15][16][17][18][19][20][21] However, this argument rests on anecdotal gossip mainly. In his fiction, Hemingway never treats homosexuality in an unambiguous or even homophobic way, though of course he occasionally writes about characters who exhibit homophobic traits (such as Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises). In those of his works which feature homosexuality as a major theme, he shows himself a subtle and balanced chronicler of human conflict (e.g. in "A Simple Inquiry," "The Sea Change," and The Garden of Eden).

These relationships provided inspiration for Hemingway's first full-length novel, The Sun Also Rises (1926). The novel was semi-autobiographical, following a group of expatriate Americans around Paris and Spain. The climactic scenes of the novel are set in Pamplona, during the fiesta that the novel made famous throughout Europe and the U.S. The novel was a success and met with critical acclaim. While Hemingway had initially claimed that the novel was an obsolete form of literature, he was apparently inspired to write it after reading Fitzgerald's manuscript for The Great Gatsby.[citation needed]

Hemingway divorced Hadley Richardson in 1927 and married Pauline Pfeiffer, a devout Roman Catholic from Piggott, Arkansas. Pfeiffer was an occasional fashion reporter, publishing in magazines such as Vanity Fair and Vogue.[22] Hemingway converted to Catholicism himself at this time. That year saw the publication of Men Without Women, a collection of short stories, containing "The Killers", one of Hemingway's best-known and most-anthologized stories. In 1928, Hemingway and Pfeiffer moved to Key West, Florida, to begin their new life together. However, their new life was soon interrupted by yet another tragic event in Hemingway's life.

In 1928, Hemingway's father, Clarence, troubled with diabetes and financial instabilities, committed suicide using an old Civil War pistol. This greatly hurt Hemingway and is perhaps played out through Robert Jordan's fathers' suicide in the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. He immediately traveled to Oak Park to arrange the funeral and stirred up controversy by vocalizing what he thought to be the Catholic view, that suicides go to Hell. At about the same time, Harry Crosby, founder of the Black Sun Press and a friend of Hemingway's from his days in Paris, also committed suicide.

In that same year, Hemingway's second son, Patrick, was born in Kansas City (his third son, Gregory, would be born to the couple a few years later). It was a Caesarean birth after difficult labor, details of which were incorporated into the concluding scene of A Farewell to Arms. Hemingway lived and wrote most of A Farewell to Arms plus several short stories at Pauline's parents' house in Piggott, Arkansas. The Pfeiffer House and Carriage House has since been converted into a museum owned by Arkansas State University.

Published in 1929, A Farewell to Arms recounts the romance between Frederic Henry, an American soldier, and Catherine Barkley, a British nurse. The novel is heavily autobiographical: the plot was directly inspired by his relationship with Agnes von Kurowsky in Milan; Catherine's parturition was inspired by the intense labor pains of Pauline in the birth of Patrick; the real-life Kitty Cannell inspired the fictional Helen Ferguson; the priest was based on Don Giuseppe Bianchi, the priest of the 69th and 70th regiments of the Brigata Ancona. While the inspiration of the character Rinaldi is obscure, he had already appeared in In Our Time. A Farewell to Arms was published at a time when many other World War I books were prominent, including Frederic Manning's Her Privates We, Erich Maria Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front, Richard Aldington's Death of a Hero, and Robert Graves' Goodbye to All That. The success of A Farewell to Arms made Hemingway financially independent.

Early critical interplay

Hemingway's early works sold well and were generally received favorably by critics. This success elicited some crude and pretentious behavior from him, even in these formative years of his career. For example, he began to tell F. Scott Fitzgerald how to write; he also claimed that the novelist Ford Maddox Ford was sexually impotent. Hemingway in turn was the subject of much criticism. The journal Bookman attacked him as a dirty writer. According to Fitzgerald, McAlmon, the publisher of his first non-commercial book, labeled Hemingway "a fag and a wife-beater"[23] and claimed that Pauline, his second wife, was a lesbian (she was alleged to have had lesbian affairs after their divorce). Gertrude Stein criticized him in her book The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, suggesting that he had derived his prose style from her own and from Sherwood Anderson's.[24]

Max Eastman disparaged Hemingway harshly, asking him to "come out from behind that false hair on the chest" (this led to a physical confrontation between the two in the offices of Scribners that Maxwell Perkins witnessed and later described in a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald). Eastman would go on to write an essay entitled Bull in the Afternoon, a satire of Hemingway's Death in the Afternoon. Another facet of Eastman's criticism consisted of the suggestion that Hemingway give up his lonely, tight-lipped stoicism and write about contemporary social affairs. Hemingway did so for at least a short time; his article Who Murdered the Vets? for New Masses, a leftist magazine, and To Have and Have Not displayed a certain heightened social awareness.

Of criticism, Hemingway said, "You can write anytime people will leave you alone and not interrupt you. Or rather you can if you will be ruthless enough about it. But the best writing is certainly when you are in love", in an interview in The Paris Review, with its founder, George Plimpton, in 1958.

Key West and the Spanish Civil War

Following the advice of John Dos Passos, Hemingway returned to Key West, Florida in 1931, where he established his first American home, which has since been converted to a museum. From this 1851 solid limestone house—a wedding present from Pauline's uncle—Hemingway fished in the waters around the Dry Tortugas with his longtime friend Waldo Pierce, went to the famous bar Sloppy Joe's, and occasionally traveled to Spain, gathering material for Death in the Afternoon and Winner Take Nothing. Over the next 9 years, until the end of this marriage in 1940, and then in a second period throughout the 1950s, Hemingway would do an estimated 70% of his lifetime's writing in the writer's den in the upper floor of the converted garage, in back of this house.

Death in the Afternoon, a book about bullfighting, was published in 1932. Hemingway had become an aficionado after seeing the Pamplona fiesta of 1925, fictionalized in The Sun Also Rises. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway extensively discussed the metaphysics of bullfighting: the ritualized, almost religious practice. In his writings on Spain, he was influenced by the Spanish master Pío Baroja (when Hemingway won the Nobel Prize, he traveled to see Baroja, then on his death bed, specifically to tell him he thought Baroja deserved the prize more than he).

A safari in the fall of 1933 led him to Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya, moving on to Tanzania, where he hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara and west and southeast of the present-day Tarangire National Park. 1935 saw the publication of Green Hills of Africa, an account of his safari. The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber were the fictionalized results of his African experiences.

In 1937, Hemingway traveled to Spain in order to report on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance. While there, Hemingway broke his friendship with John Dos Passos because, despite warnings, Dos Passos continued to report on the atrocities of not only the fascist Nationalists whom Hemingway disliked, but also those of the elected and radicalized left-leaning Republicans whom he favored.[25][26] In this context Hemingway's colleague and associate Herbert Matthews, who would become more well known for his favorable reports on Fidel Castro, showed a similar bias for the Republican side as Hemingway. Hemingway, who was a convert to Catholicism during his marriage to his wife Pauline, began to question his religion at this time, eventually leaving the church (though friends indicate that he had "funny ties" to Catholicism for the rest of his life). The war also strained Hemingway's marriage. Pauline Pfieffer was a devout Catholic and, as such, sided with the fascist, pro-Catholic regime of Franco, whereas Hemingway supported the Republican government. During this time, Hemingway wrote a little known essay, The Denunciation, which would not be published until 1969 within a collection of stories, the Fifth Column and Four Stories of the Spanish Civil War. The story seems autobiographical, suggesting that Hemingway might have been an informant for the Republic as well as a weapons instructor during the war.[27]

Some health problems characterized this period of Hemingway's life: an anthrax infection, a cut eyeball, a gash in his forehead, grippe, toothache, hemorrhoids, kidney trouble from fishing, torn groin muscle, finger gashed to the bone in an accident with a punching ball, lacerations (to arms, legs, and face) from a ride on a runaway horse through a deep Wyoming forest, and a broken arm from a car accident.

The Forty-Nine Stories

In 1938—along with his only full-length play, titled The Fifth Column—49 stories were published in the collection The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories. Hemingway's intention was, as he openly stated in his foreword, to write more. Many of the stories that make up this collection can be found in other abridged collections, including In Our Time, Men Without Women, Winner Take Nothing, and The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

Some of the collection's important stories include Old Man at the Bridge, On The Quai at Smyrna, Hills Like White Elephants, One Reader Writes, The Killers and (perhaps most famously) A Clean, Well-Lighted Place. While these stories are rather short, the book also includes much longer stories, among them The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Francisco Franco and the Nationalists defeated the Republicans, ending the Spanish Civil War in the spring of 1939. Hemingway lost an adopted homeland to Franco's fascists, and would later lose his beloved Key West, Florida home due to his 1940 divorce. A few weeks after the divorce, Hemingway married his companion of four years in Spain, Martha Gellhorn, his third wife. His novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was published in 1940. It was written in 1939 in Cuba and Key West, and was finished in July, 1940. The long work, which takes place during the Spanish Civil War, was based on real events and tells of an American named Robert Jordan fighting with Spanish soldiers on the Republican side. It was largely based upon Hemingway's experience of living in Spain and reporting on the war. It is one of his most notable literary accomplishments. The title is taken from the penultimate paragraph of John Donne's Meditation XVII.

World War II and its aftermath

The United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, and for the first time in his life, Hemingway sought to take part in naval warfare. Aboard the Pilar, now a Q-Ship, Hemingway's crew was charged with sinking German submarines threatening shipping off the coasts of Cuba and the United States (Martha Gellhorn always viewed the sub-hunting as an excuse for Hemingway and his friends to get gas and booze for fishing). As the FBI took over Caribbean counter-espionage—J. Edgar Hoover was suspicious of Hemingway from the start, and would become more so later—Ernest went to Europe as a war correspondent for Collier's magazine. There Hemingway observed the D-Day landings from an LCVP (landing craft), although he was not allowed to go ashore. He later became angry that his wife, Martha Gellhorn—by then, more a rival war correspondent than a wife—had managed to get ashore in the early hours of June 7 dressed as a nurse, after she had crossed the Atlantic to England in a ship loaded with explosives. Still later, at Villedieu-les-Poêles, he allegedly threw three grenades into a cellar where SS officers were hiding.[citation needed] Hemingway acted as an unofficial liaison officer at Château de Rambouillet, and afterwards formed his own partisan group which, in his telling, took part in the liberation of Paris. This claim has been challenged by many historians, who say the only thing Hemingway liberated was the Ritz Hotel Bar. Nevertheless, he was unquestionably on the scene. [citation needed] After the war Hemingway was boasting off in a letter to Arthur Mizener with having killed at least 122 German Prisoners of War in cold blood.

After the war, Hemingway started work on The Garden of Eden, which was never finished and would be published posthumously in a much-abridged form in 1986. At one stage, he planned a major trilogy which was to comprise "The Sea When Young", "The Sea When Absent" and "The Sea in Being" (the latter eventually published in 1952 as The Old Man and the Sea). He spent time in a small Italian town called Acciaroli (located approximately 136 km south of Naples), where he was often seen walking around, bottle in hand. There was also a "Sea-Chase" story; three of these pieces were edited and stuck together as the posthumously-published novel Islands in the Stream (1970).

Newly divorced from Gellhorn after four contentious years, Hemingway married war correspondent Mary Welsh Hemingway, whom he had met overseas in 1944. He returned to Cuba, and in 1945 at the Soviet Embassy became public witness to the Rolando Masferrer schism within the Cuban communist party (García Montes, and Alonso Ávila, 1970 p. 362).

Hemingway's first novel after For Whom the Bell Tolls was Across the River and into the Trees (1950), set in post-World War II Venice. He derived the title from the last words of American Civil War Confederate General Stonewall Jackson. Enamored of a young Italian girl (Adriana Ivancich) at the time, Hemingway wrote Across the River and into the Trees as a romance between a war-weary Colonel Cantwell (based on his friend, then Colonel Charles Lanham) and the young Renata (clearly based on Adriana; "Renata" means "reborn" in Italian). The novel received largely bad reviews, many of which accused Hemingway of tastelessness, stylistic ineptitude, and sentimentality; however this criticism was not shared by all critics.

Later years

One section of the sea trilogy was published as The Old Man and the Sea in 1952. That novella's enormous success satisfied and fulfilled Hemingway. It earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 1953. The next year he was awarded with the Nobel Prize in Literature. Upon receiving the latter, he noted with uncharacteristic humility that he would have been "happy; happier...if the prize had been given to that beautiful writer Isak Dinesen", referring to Danish writer Karen Blixen.[28] These awards helped to restore his international reputation.

Then, his legendary bad luck struck once again; on a safari, he was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes; he sprained his right shoulder, arm, and left leg, had a grave concussion, temporarily lost vision in his left eye and the hearing in his left ear, suffered paralysis of the spine, a crushed vertebra, ruptured liver, spleen and kidney, and first degree burns on his face, arms, and leg. Some American newspapers mistakenly published his obituary, thinking he had been killed. [29]

As if this were not enough, he was badly injured one month later in a bushfire accident, which left him with second degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm. The pain left him in prolonged anguish, and he was unable to travel to Stockholm to accept his Nobel Prize.

A glimmer of hope came with the discovery of some of his old manuscripts from 1928 in the Ritz cellars, which were transformed into A Moveable Feast. Although some of his energy seemed to be restored, severe drinking problems kept him down. His blood pressure and cholesterol were perilously high, he suffered from aortal inflammation, and his depression was aggravated by his heavy drinking. However, in October of 1956, Hemingway found the strength to travel to Madrid and act as a pallbearer at Pío Baroja's burial. Baroja was one of Hemingway's literary influences.

Following the revolution in Cuba and the ousting of General Fulgencio Batista in 1959, expropriations of foreign owned property led many Americans to return to the United States. Hemingway chose to stay a little longer. It is commonly said that he shared good relations with Fidel Castro and declared his support for the revolution, and he is quoted as wishing Castro "all luck" with running the country.[30] [31]. However, the Hemingway account "The Shot" [32] is used by Cabrera Infante [33] and others [34] [35] as evidence of conflict between Hemingway and Fidel Castro dating back to 1948 and the killing of "Manolo" Castro a friend of Hemingway. Additional information in this regard is found in [36]. Hemingway came under surveillance by the FBI both during World War II and afterwards (most probably because of his long association with marxist Spanish Civil War veterans[37] who were again active in Cuba)] for his residence and activities in Cuba.[31] In 1960, he left the island and Finca Vigía, his estate outside Havana, that he owned for over twenty years. The official Cuban government account is that it was left to the Cuban government, which has made it into a museum devoted to the author.[38] In 2001, Cuba's state-owned tourism conglomerate, El Gran-Caribe SA, began licensing the La Bodeguita del Medio international restaurant chain relying largely on the original Havana restaurant's association with Hemingway, a frequent visitor.[39].

On 26 February 1960, Ernest Hemingway was unable to get his bullfighting narrative The Dangerous Summer to the publishers. He therefore had his wife Mary summon his friend, Life Magazine bureau head Will Lang Jr., to leave Paris and come to Spain. Hemingway persuaded Lang to let him print the manuscript, along with a picture layout, before it came out in hardcover. Although not a word of it was on paper, the proposal was agreed upon. The first part of the story appeared in Life Magazine on September 5 1960, with the remaining installments being printed in successive issues.

Hemingway was upset by the photographs in his The Dangerous Summer article. He was receiving treatment in Ketchum, Idaho for high blood pressure and liver problems — and also electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for depression and continued paranoia, although this may in fact have helped to precipitate his suicide, since he reportedly suffered significant memory loss as a result of the shock treatments. He also lost weight, his 6-foot (183 cm) frame appearing gaunt at 170 pounds (77 kg, 12st 2lb).

Suicide

Hemingway attempted suicide in the spring of 1961, and received ECT treatment again. Some three weeks short of his 62nd birthday, he took his own life on the morning of July 2, 1961 at his home in Ketchum, Idaho, with a shotgun blast to the head. Judged not mentally responsible for his final act, he was buried in a Roman Catholic service. Hemingway himself blamed the ECT treatments for "putting him out of business" by destroying his memory; some medical and scholarly opinion has been receptive to this view, although others, including one of the physicians who prescribed the electroshock regimen, dispute that opinion.[citation needed]

Hemingway is believed to have purchased the weapon he used to commit suicide at Abercrombie & Fitch, which was then an elite excursion goods retailer and firearm supplier. (The Shotgun was a Boss & Co ordered through A&F)[40] In a particularly gruesome suicide, he rested the gun butt of the double-barreled shotgun on the floor of a hallway in his home, leaned over it to put the twin muzzles to his forehead just above the eyes, and pulled both triggers. [41] Despite the circumstances, the coroner, at request of the family, did not do an autopsy. [42]

Other members of Hemingway's immediate family also committed suicide, including his father, Clarence Hemingway, his siblings Ursula and Leicester, and possibly his granddaughter Margaux Hemingway. Some believe that certain members of Hemingway's paternal line had a genetic condition or hereditary disease known as haemochromatosis, in which an excess of iron concentration in the blood causes damage to the pancreas and also causes depression or instability in the cerebrum.[citation needed] Hemingway's physician father is known to have developed bronze diabetes owing to this condition in the years prior to his suicide at age fifty-nine. Throughout his life, Hemingway had been a heavy drinker, succumbing to alcoholism in his later years.

Hemingway suffered from manic depression, now known as bipolar disorder, and was subsequently treated with electroshock therapy at Menninger Clinic.[43] He later credited this to his self-proclaimed memory loss which he cited as a reason for not wanting to live. [43]

Hemingway is interred in the town cemetery in Ketchum, Idaho, at the north end of town. A memorial was erected in 1966. It is inscribed with a eulogy he wrote for a friend, Gene Van Guilder:

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

Now he will be a part of them forever

Ernest Hemingway - Idaho - 1939

Celebrating Hemingway's love for Idaho and the frontier, The Ernest Hemingway Festival [5] takes place annually in Ketchum and Sun Valley in late September with scholars, a reading by the PEN/Hemingway Award winner and many more events, including historical tours, open mic nights and a sponsored dinner at Hemingway's home in Warm Springs now maintained by the Nature Conservancy in Ketchum.

Family

Parents

- Clarence Hemingway. Born September 4, 1871, died December 6, 1928

- Grace Hall Hemingway. Born June 15, 1872, died June 28, 1951

Siblings

- Marcelline Hemingway. Born January 15, 1898, died December 9, 1963

- Ursula Hemingway. Born April 29, 1902, died October 30, 1966

- Madelaine Hemingway. Born November 28, 1904, died January 14, 1995

- Carol Hemingway. Born July 19, 1911, died October 27, 2002

- Leicester Hemingway. Born April 1, 1915, died September 13, 1982

Wives and children

- Elizabeth Hadley Richardson. Married September 3, 1921, divorced April 4, 1927.

- Son, John Hadley Nicanor "Jack" Hemingway (aka Bumby). Born October 10, 1923, died December 1, 2000.

- Granddaughter, Joan (Muffet) Hemingway

- Granddaughter, Margaux Hemingway

- Granddaughter, Mariel Hemingway

- Pauline Pfeiffer. Married May 10, 1927, divorced November 4, 1940.

- Son, Patrick. Born June 28, 1928.

- Son, Gregory Hemingway (called 'Gig' by Hemingway; later called himself 'Gloria'). Born November 12, 1931, died October 1, 2001.

- Grandchildren, Patrick, Edward, Sean, Brendan, Vanessa, Maria, John and Lorian Hemingway

- Martha Gellhorn. Married November 21, 1940, divorced December 21, 1945.

- Mary Welsh. Married March 14, 1946.

- On 19 August 1946, she miscarried due to ectopic pregnancy.

Posthumous publications

Hemingway was a prolific letter writer and, in 1981, many of these were published by Scribner in Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters. It was met with some controversy as Hemingway himself stated he never wished to publish his letters. Further letters were published in a book of his correspondence with his editor Max Perkins, The Only Thing that Counts [1996].

A long-term project is now underway to publish the thousands of letters Hemingway wrote during his lifetime. The project is being undertaken as a joint venture by Penn State University and the Ernest Hemingway Foundation. Sandra Spanier, Professor of English and wife of Penn State president Graham Spanier, is serving as general editor of the collection.[6]

Hemingway was still writing up to his death. All of the unfinished works which were Hemingway's sole creation have been published posthumously; they are A Moveable Feast, Islands in the Stream, The Nick Adams Stories (portions of which were previously unpublished), The Dangerous Summer, and The Garden of Eden.[44] In a note forwarding "Islands in the Stream", Mary Hemingway indicated that she worked with Charles Scribner, Jr. on "preparing this book for publication from Ernest's original manuscript". She also stated that "beyond the routine chores of correcting spelling and punctuation, we made some cuts in the manuscript, I feeling that Ernest would surely have made them himself. The book is all Ernest's. We have added nothing to it." Some controversy has surrounded the publication of these works, insofar as it has been suggested that it is not necessarily within the jurisdiction of Hemingway's relatives or publishers to determine whether these works should be made available to the public. For example, scholars often disapprovingly note that the version of The Garden of Eden published by Charles Scribner's Sons in 1986, though in no way a revision of Hemingway's original words, nonetheless omits two-thirds of the original manuscript.[45]

The Nick Adams Stories appeared posthumously in 1972. What is now considered the definitive compilation of all of Hemingway's short stories was published as The Complete Short Stories Of Ernest Hemingway, first compiled and published in 1987. As well, in 1969 The Fifth Column and Four Stories Of The Spanish Civil War was published. It contains Hemingway's only full length play, The Fifth Column, which was previously published along with the First Forty-Nine Stories in 1938, along with four unpublished works written about Hemingway's experiences during the Spanish Civil War.

In 1999, another novel entitled True at First Light appeared under the name of Ernest Hemingway, though it was heavily edited by his son Patrick Hemingway. Six years later, Under Kilimanjaro, a re-edited and considerably longer version of True at First Light appeared. In either edition, the novel is a fictional account of Hemingway's final African safari in 1953–1954. He spent several months in Kenya with his fourth wife, Mary, before his near-fatal plane crashes.[46] Anticipation of the novel, whose manuscript was completed in 1956, adumbrates perhaps an unprecedentedly large critical battle over whether it is proper to publish the work (many sources mention that a new, light side of Hemingway will be seen as opposed to his canonical, macho image[47]), even as editors Robert W. Lewis of University of North Dakota and Robert E. Fleming of University of New Mexico have pushed it through to publication; the novel was published on September 15 2005.

Also published posthumously were several collections of his work as a journalist. These contain his columns and articles for Esquire Magazine, The North American Newspaper Alliance, and the Toronto Star; they include Byline: Ernest Hemingway edited by William White, and Hemingway: The Wild Years edited by Gene Z. Hanrahan. Finally, a collection of introductions, forwards, public letters and other miscellanea was published as Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame in 2005.

Influence and legacy

The influence of Hemingway's writings on American literature was considerable and continues today. Indeed, the influence of Hemingway's style was so widespread that it may be glimpsed in much contemporary fiction,[citation needed] as writers draw inspiration either from Hemingway himself or indirectly through writers who more consciously emulated Hemingway's style. In his own time, Hemingway affected writers within his modernist literary circle. James Joyce called "A Clean, Well Lighted Place" "one of the best stories ever written". Pulp fiction and "hard boiled" crime fiction (which flourished from the 1920s to the 1950s) often owed a strong debt to Hemingway. During World War II, J. D. Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence.[48] In one letter to Hemingway, Salinger wrote that their talks "had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war," and jokingly "named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs."[49] Hunter S. Thompson often compared himself to Hemingway, and terse Hemingway-esque sentences can be found in his early novel, The Rum Diary. Thompson's later suicide by gunshot to the head mirrored Hemingway's. Hemingway's terse prose style--"Nick stood up. He was all right"-- is known to have inspired Bret Easton Ellis, Chuck Palahniuk, Douglas Coupland and many Generation X writers. Hemingway's style also influenced Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation writers. Hemingway also provided a role model to fellow author and hunter Robert Ruark, who is frequently referred to as "the poor man's Ernest Hemingway". In Latin American literature, Hemingway's impact can be seen in the work of fellow Nobel Prize winner Gabriel García Márquez. Beyond the more formal literature authors, popular novelist Elmore Leonard, who authored scores of Western and Crime genre novels, cites Hemingway as his preeminent influence and this is evident in his tightly written prose. Though he never claimed to write serious literature, he did say, "I learned by imitating Hemingway....until I realized that I didn't share his attitude about life. I didn't take myself or anything as seriously as he did."

Awards and honors

During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded with:

- Silver Medal of Military Valor (medaglia d'argento) in World War I

- Bronze Star (War Correspondent-Military Irregular in World War II) in 1947

- Pulitzer Prize in 1953 (for The Old Man and the Sea)

- Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954 (for his lifetime literary achievements)

In popular culture

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (September 2007) |

- In 1999, Michael Palin retraced the footsteps of Hemingway, in Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure, a BBC television documentary, one hundred years after the birth of his favorite writer. The journey took him through many sites including Chicago, Paris, Italy, Africa, Key West, Cuba, and Idaho. Together with photographer Basil Pao, Palin also created a book version of the trip, with many beautiful pictures and much more detail than in the TV version. The text of the book is available for free on Palin's website.

- Palin also wrote a novel, Hemingway's Chair, about a young English postal worker and Hemingway aficionado who attempts to take charge like his hero when the postal office where he works is falling into corporate hands.

- Hemingway is also featured in a Ween song called "Don't Laugh (I Love you)".

- Since 1987, actor-writer Ed Metzger has portrayed the life of Ernest Hemingway in his one-man stage show, Hemingway: On The Edge, featuring stories and anecdotes from Hemingway's own life and adventures. Metzger quotes Hemingway, "My father told me never kill anything you're not going to eat. At the age of 9, I shot a porcupine. It was the toughest lesson I ever had." More information about the show is available at his website

- Hemingway's World War II experiences in Cuba have been novelized by Dan Simmons as a spy thriller, The Crook Factory.

- Science fiction novelist Joe Haldeman won the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award for his novella, The Hemingway Hoax, a story which explored the effect that Hemingway's lost stories might have had upon twentieth century history.

- In Harry Turtledove's Alternate History Timeline-191, Hemingway shows up as a character who drove ambulances on the US-Canadian Front in Quebec during the Great War. The character had part of his reproductive organs shot off in the war, giving him severe depression and suicidal tendencies, which ultimately led to him accidentally killing both his lover and himself.

- In Dave Sim's graphic novel Cerebus, the story arc "Form and Void" features Ham and Mary Ernestway, fictional versions of Hemingway and his wife Mary. The last few years of Hemingway's life, including his electroshock therapy, the safari in which he was badly injured, and his suicide are used as plot points for the story.

- The 1988 film The Moderns locates itself in Hemingway's Paris with a central character named Nick Hart, who befriends Hemingway.

- A film based on Hemingway's relationship with World War II correspondent Martha Gellhorn is set to start production in 2007 under director Philip Kaufman and starring Emmy-winner James Gandolfini.

- Hemingway was featured in Warner Bros. Animation television shows of the 1990s. His first appearance was in a segment in the fourth season of Animaniacs titled "Papers for Papa". In this episode, Hemingway, trapped in writer's block, swears off of writing just as Yakko, Wakko and Dot show up with a shipment of office supplies. When Hemingway refuses to sign for the delivery, the Warners chase him around the world, during which they catch a swordfish, get in a bullfight, and climb Mount Everest.

- In his novel Immortality (1991), Milan Kundera has Hemingway meeting Goethe in the afterlife where they discuss the immortality of writers and of their works.

- Hemingway, played by Jay Underwood, was a recurring character in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. In one episode, set in Northern Italy in 1916, Hemingway the ambulance driver gives young Indy (Sean Patrick Flanery) advice about women -- only to discover that he and Indy are rivals for the heart of the same woman. (The episode shows Indy unwittingly influencing Hemingway's future writing, by reciting the Elizabethan poem, A Farewell to Arms by George Peele.) In another episode, set in Chicago in 1920, Hemingway the newspaper reporter helps Indy and a young Eliot Ness in their investigation of the murder of gangster James Colosimo.

- The 1993 motion picture Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, about the friendship of two retired men, one Irish, one Cuban, in a seaside town in Florida, starred Robert Duvall, Richard Harris, Shirley MacLaine, Sandra Bullock, and Piper Laurie.

- The 1996 motion picture In Love and War, based on the book Hemingway In Love and War by Henry S. Villard and James Nagel, was the story of the young reporter Ernest Hemingway (played by Chris O'Donnell) as an ambulance driver in Italy during World War I. While bravely risking his life in the line of duty, he is injured and ends up in the hospital, where he falls in love with his nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky (Sandra Bullock).

- In Jacques Poulin's novel My Sister's Blue Eyes (Yeux bleus de Mistassini), bookstore owner Jack Waterman is inspired to buy a woodstove after reading Hemingway's A Moveable Feast. He has employee and protege Jimmy read and translate Hemingway. When Jimmy travels to France, he looks for the apartment where Hemingway lived with wife Hadley. He also visits the original site of Sylvia Beach's Shakespeare and Company, as well as the store's new location.

- Two of David Fincher's films make reference to Hemingway. At the end of "Se7en", Detective Somerset (Morgan Freeman) quotes Hemingway, saying "Ernest Hemingway once wrote the world is a fine place and worth fighting for. I agree with the second part." In "Fight Club", Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), states that he would like to fight Hemingway during a conversation with Edward Norton' character, Jack, regarding famous personalities they would like to fight.

- Hemingway's downfall was namelessly described in Rush's 1982 song, "Losing It", which told the tales of a couple of different people, a dancer and a writer, who could no longer perform their professions due to age, health, or other reasons.

- The Streetlight Manifesto song 'Here's to Life' is a tribute to various authors and musicians whose actions had influenced Tomas Kalnoky's life. Hemingway is one of the few people mentioned.

Anecdotes

- In a boxing match with friend and writer Morley Callaghan, Hemingway's lip was cut. Hemingway spit blood into Callaghan's face and said: "The bullfighters do that when they are injured, it is how they show contempt."

- In a letter to Ezra Pound, Hemingway describes why bulls are better than literary critics: "Bulls don't run reviews. Bulls of 25 don't marry old women of 55 and expect to be invited to dinner. Bulls do not get you cited as co-respondent in Society divorce trials. Bulls don't borrow money. Bulls are edible after they have been killed."[50]

- According to various biographical sources, Hemingway was six feet tall and weighed anywhere between 170 and 260 pounds at varying times in his life. His build was muscular, though he became paunchy in his middle years. He had dark brown hair, brown eyes, and habitually wore a mustache (with an occasional beard) from the age of 23 on. By age 50, he consistently wore a graying beard. He had a scar on his forehead, the result of a drunken accident in Paris in his late 20s (thinking he was flushing a toilet, he accidentally pulled a skylight down on his head). He suffered from myopia all his life, but vanity prevented him from being fitted with glasses until he was 32 (and very rarely was he photographed wearing them). He was fond of tennis and boxing, fonder of fishing and hunting, and hated New York City.

- Though Hemingway did not have a favorable opinion of his hometown of Oak Park, IL, describing it as a town of "Wide yards and narrow minds," the town has adopted a favorable opinion about him. Today a Hemingway Museum exists in that town. Every summer a Hemingway festival is staged in that city, complete with a "running of the bulls", using a fake bull on wheels. This festival also features readings of the author's work and Spanish food.

- The original short short story. In the 1920s, Hemingway bet his colleagues $10 that he could write a complete story in just six words. They paid up. His story: "For sale: Baby shoes, Never worn." [51] In a contest in Wired magazine inspired by Hemingway's story, 33 authors recently submitted 6-word efforts.[52]

Works

Notes

- ^ From Childhood at The Hemingway Resource Center.

- ^ Two different sources disagree on how long this habit of his mother's lasted. A note from a PBS lecture series states that this habit lasted for two years; Grauer claims she stopped when he was 6.

- ^ ""Lardner Connections"". Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ Many such anecdotes are compiled at the centennial commemoration page of the Kansas City Star.

- ^ Burgess, 1978, p. 24.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ National Post article on Toronto's Humewood-Cedarvale neighborhood

- ^ Brown, Alan, "Literary Landmarks of Chicago," 2004, Starhill Press, ISBN 0-913515-50-7.

- ^ On August 10, 1943, Hemingway typed a letter to Archibald MacLeish discussing Pound's mental health and other literary matters.

- ^ In a conversation with John Peale Bishop, quoted in Hemingway, Cowley, ed, 1944, p. xiii.

- ^ Dateline: Toronto, Foreword, pp xxv-xxvii, Charles Scribner Jr.

- ^ "Hem and The Star: Parting was inevitable". The Toronto Star. 1986-02-02.

- ^ Thurston, Michael: "Genre, Gender, and Truth in Death in the Afternoon", The Hemingway Review, Spring 1998

- ^ Ernest Hemingway, Death in the Afternoon, p.71

- ^ Moddelmog, Debra A. "Reconstructing Hemingway's Identity: Sexual Politics, the Author, and the Multicultural Classroom." Narrative. 1.3.

- ^ Bederman, Gail. "Civilization, The Decline of Middle-Class Manliness, and Ida B. Wells's Anti-Lynching Campaign)." Gender and American History Since 1890. New York: Routledge, 1993

- ^ Bennett, Warren. "Sexual Identity in `The Sea Change.'" Hemingway's Neglected Short Fiction: New Perspectives. Ed. Susan F. Beegel. Ann Arbor: UMI Research P, 1989.

- ^ Brian, Denis. The True Gen: An Intimate Portrait of Hemingway by Those Who Knew Him. New York: Grove Press, 1988.

- ^ Chauncey, George Jr. "Christian Brotherhood or Sexual Perversion?: Homosexual Identities and the Construction of Sexual Boundaries in the World War I Era." Gender and American History Since 1890. New York: Routledge, 1993

- ^ Fone, Byrne R. S. A Road to Stonewall: Male Homosexuality and Homophobia in English and American Literature,. New York: Twayne, 1995 The Ernest Hemingway Foundation of Oak Park. "Literature Awards". 2/99 http://www.ehfop.org/life

- ^ Donnell, Sean M. Hemingway's Short Fiction and the Crisis of Middle-Class Masculinity. 2002.).

- ^ Hemingway Resource Center

- ^ Burgess, 1978, p. 57.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles by Stephen Koch, published 2005 ISBN

- ^ The Spanish Civil War (1961) by Hugh Thomas

- ^ The Spanish Civil War (1961) by Hugh Thomas

- ^ From The New York Times Book Review, November 7, 1954.

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway Quick Facts". encarta.

- ^ "Hemingway's Marriage to Mary Welsh. His last days".

- ^ a b "Homing To The Stream :Ernest Hemingway In Cuba". Cite error: The named reference "eh" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest 1951 The Shot. True the men’s magazine. April 1951. pp. 25-28

- ^ "An Interview with Guillermo Cabrera Infante".

- ^ Gonzalez Echevarria, Roberto 1980 The Dictatorship of Rhetoric/the Rhetoric of Dictatorship: Carpentier, Garcia Marquez, and Roa Bastos. Latin American Research Review, Vol. 15, No. 3 (1980), pp. 205-228 "For example, the assassination of Manolo Castro is retold by alluding to Hemingway's "The Shot,…""

- ^ http://hemingway-castro-foes.blogspot.com/

- ^ Raimundo, Daniel Efrain 1994 Habla el Coronel Orlando Piedra (Coleccion Cuba y sus Jueces), Ediciones Universal ISBN-10 ISBN-13: Pages 93-94 refer to the death of Manolo Castro, and offers the insight that it was Rolando Masferrer’s men who, rather than the police who, were chasing after Fidel Castro with lethal intent. According to this account Castro is captured in the company of a woman and child as he tries to flee to Venezuela via the Cuban airport of Rancho Boyeros south of Havana by the Cuban Bureau of Investigation as witnessed by sergeant of that organization Joaquin Tasas. Castro is released the next day. This matter is a little odd since Fidel Castro was believed to have organized the death of Manolo Castro (p. 99). This version is a close fit the scenario described in "The Shot/."

- ^ The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles by Stephen Koch, published 2005 ISBN

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/hemingwayadventure/finca.html

- ^ MILLMAN, JOEL (February 22, 2007). "Hemingway's Ties to Bar - Still Move the Mojitos". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Grauer, Neil A. "Remembering Papa." Cigar Aficionado, July/August 1999.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b "Biography for Ernest Hemingway". imdb. Amazon. 2005. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Information about these posthumous Hemingway works was taken from Charles Scribner, Jr.'s 1987 Preface to The Garden of Eden.

- ^ BookRags makes this quantitative note; it also reveals some more information about the publication of The Garden of Eden and offers some discussion of thematic content.

- ^ The Kent State University Press is the official source for this new novel's release.

- ^ See the University of North Dakota feature of editor Robert W. Lewis, for example.

- ^ Lamb, Robert Paul (Winter 1996). "Hemingway and the creation of twentieth-century dialogue - American author Ernest Hemingway" (reprint). Twentieth Century Literature. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. ISBN 0-020-01690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) p. 420, 646. - ^ [3]

- ^ Arthur C. Clarke, "Greetings, Carbon-Based Bipeds, Collected Essays", 1999, p. 354.

- ^ [4]

- ^ a b Hemingway, Ernest (2005). Dear Papa, Dear Hotch: The Correspondence of Ernest Hemingway And A. E. Hotchner. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0826216056.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

References

- Berridge, H.R. (1990). Barron's Book Notes on Ernest Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms. Stuttgart: Klett. ISBN.

- Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN.

- Baker, Carlos, ed (1962). Ernest Hemingway: Critiques of Four Major Novels. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bruccoli, Matthew J (1978). Scott and Ernest: The Authority of Failure and the Authority of Success. London: Bodley Head.

- Burgess, Anthony (1978). Ernest Hemingway (Literary Lives). London: Thames and Hudson.

- "Biography". The Hemingway Resource Center. 1996. ISBN.

- García Montes, Jorge and Antonio Alonso Ávila (1970). Historia del Partido Comunista en Cuba. Miami: Ediciones Universal. p. 362

- Cappel, Constance,"Hemingway in Michigan," 1966, 1977, 1999.

- Cappel, Constance, "Sweetgrass and Smoke," 2002,Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris.

- Hemingway, Ernest, Malcolm Cowley, ed (1944). Hemingway (The Viking Portable Library). New York: The Viking Press. OCLC 505504.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler (1995). Hemingway. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN.

- Lynn, Steve. Texts and Contexts: Writing About Literature with Critical Theory (4th Edition). New York. ISBN.

{{cite book}}: Text "publisher Longman" ignored (help); Unknown parameter|Year=ignored (|year=suggested) (help) pp. 5-7 - Young, Philip (1952). Ernest Hemingway. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. ISBN.

External links

- Timeless Hemingway

- The Hemingway Society

- The Ernest Hemingway Festival

- New York Times obituary, July 3, 1961

- Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin.

- CNN: A Hemingway Retrospective

- Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida, official website

- Hemingway's grave site

- The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center

- Hemingway’s Reading 1910-1940

- Template:Worldcat id

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from September 2007

- Articles with trivia sections from September 2007

- Ernest Hemingway

- American novelists

- American short story writers

- American essayists

- American hunters

- American journalists

- American memoirists

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- American people of the Spanish Civil War

- Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor

- Operation Overlord people

- War correspondents

- Roman Catholic writers

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- English Americans

- American military personnel of World War I

- Writers from Chicago

- People from Oak Park, Illinois

- Writers who committed suicide

- Suicides by firearm

- Suicides by firearm in the United States

- 1899 births

- 1961 deaths