Fallingwater: Difference between revisions

Add more cultural history info |

add architectural style to infobox |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

| area = |

| area = |

||

| built = 1935 |

| built = 1935 |

||

| architecture=[[Usonian]] |

|||

| architect = [[Frank Lloyd Wright]] |

| architect = [[Frank Lloyd Wright]] |

||

| added = 1974 |

| added = 1974 |

||

Revision as of 21:53, 31 January 2008

Fallingwater | |

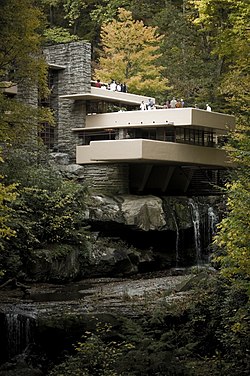

The famous view of Fallingwater | |

| Location | Mill Run, PA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Pittsburgh |

| Built | 1935 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Usonian |

| Visitation | ~135,000 |

| Added to NRHP | 1974 |

- This article is about the house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. For the house designed by Richard Neutra, see Kaufmann Desert House.

Fallingwater, also known as the Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. Residence, is a house designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935 in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, 50 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, and is part of the Pittsburgh Metro Area. The house was built partly over a waterfall in Bear Run at Rural Route 1 in the Mill Run section of Stewart Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in the Laurel Highlands of the Allegheny Mountains.

Hailed by TIME magazine shortly after its completion as Wright's "most beautiful job,"[1] the home inspired Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead,[2] and is listed among Smithsonian magazine's Life List of 28 places "to visit before ...it's too late."[3] Fallingwater was featured in Bob Vila's A&E Network production, Guide to Historic Homes of America.[4]

History

Edgar Kaufmann Sr. was a successful Pittsburgh businessman and founder of Kaufmann's Department Store. His son, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., studied architecture under Wright briefly.

Edgar Sr. had been prevailed upon by Jr. and Wright to underwrite the cost of his utopian model city. When completed, it was displayed at Kaufmann’s Department Store and Wright was a guest in the Kaufmann home, “La Tourelle”, a French Norman masterpiece that celebrated Pittsburgh architect Benno Janssen (1874-1964) had created in the stylish Fox Chapel suburb in 1923 for Edgar J. Kaufmann. The Kaufmanns and Wright were enjoying refreshments at La Tourelle when Wright, who never missed an opportunity to charm a potential client, said to Edgar Jr. in tones that the elder Kaufmanns were intended to overhear, “Edgar, this house is not worthy of your parents…” The remark spurred the Kaufmann’s interest in something worthier. Fallingwater would become the end result.

The Kaufmanns owned some property outside Pittsburgh with a waterfall and some cabins. When the cabins at their camp had deteriorated to the point that something had to be rebuilt, Mr. Kaufmann contacted Wright.

Initially, the Kaufmanns assumed the idea of Wright designing a house that would overlook the waterfall. Wright asked for a survey of the area around the waterfall, which was performed by Fayette Engineering Company of Uniontown, Pennsylvania and included all of the boulders, trees and topography. They were unprepared to hear Wright's suggestion to build a house positioned over a waterfall.[5] At the time of its construction, the structure cost $155,000.[6]

Fallingwater was the family's weekend home from 1937 to 1963. In 1963, Kaufmann, Jr. donated the property to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. In 1964 it was opened to the public as a museum and nearly four million people have visited the house since (as of July 2006). It currently hosts more than 120,000 visitors each year.[6]

Style

Fallingwater stands as one of Wright's greatest masterpieces both for its dynamism and for its integration with the striking natural surroundings. The extent of Wright's genius in integrating every detail of this design can only be hinted at in photographs. This organically designed private residence was intended to be a nature retreat for its owners. The house is well-known for its connection to the site: it is built on top of an active waterfall which flows beneath the house. The fireplace hearth in the living room is composed of boulders found on the site and upon which the house was built — one set of boulders which was left in place protrudes slightly through the living room floor. Wright had initially intended that these boulders would be cut flush with the floor, but this had been one of the Kaufmann family's favorite sunning spots, so Mr. Kaufmann insisted that it be left as it was. The stone floors are waxed, while the hearth is left plain, giving the impression of dry rocks protruding from a stream.

Integration with the setting extends even to small details. For example, where glass meets stone walls, there is no metal frame; rather, the glass is caulked directly to the stone. There are stairways directly down to the water. And in the "bridge" that connects the main house to the guest and servant building, a natural boulder drips water inside, which is then directed back out. Bedrooms are small, some even with low ceilings, perhaps to encourage people outward toward the open social areas, decks, and outdoors.

The active stream (which can be heard constantly throughout the house), immediate surroundings, and locally quarried stone walls and cantilevered terraces (resembling the nearby rock formations) are meant to be in harmony, in line with Wright's interest in making buildings that were more "organic" and which thus seemed to be more engaged with their surroundings. Although the waterfall can be heard throughout the house, it can't be seen without going outside. The design incorporates broad expanses of windows and the balconies are off main rooms giving a sense of the closeness of the surroundings. The experiential climax of visiting the house is an interior staircase leading down from the living room allowing direct access to the rushing stream beneath the house.

Wright's views of what would be the entry have been argued about; still, the door Wright considered the main door is tucked away in a corner and is rather small. Wright's idea of the grand facade for this house is from the perspective of all the famous pictures of the house, looking up from downstream, viewing the opposite corner from the main door.

On the hillside above the main house is a four-car carport (though the Kaufmanns had requested a garage), servants' quarters, and a guest bedroom. This attached outbuilding was built one year later using the same quality of materials and attention to detail as the main house. Just uphill from it is a small swimming pool, continually fed by a natural water, which then overflows to the river below.

Structural problems

Fallingwater's structural system includes a series of bold reinforced concrete cantilevered balconies. However, the house had problems from the beginning. Pronounced sags were noticed immediately with both of the prominent balconies - the living room and the second floor.[7]

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy conducted an intensive program to preserve and restore Fallingwater. The structural work was completed in 2002. This involved a detailed study of the original design documents, observing and modeling the structure's behavior, then developing and implementing a repair plan.

While Wright had been pondering the architectural design for months,[8] results of the study indicated that the original structural design and plan preparation had been rushed and the cantilevers had significantly inadequate reinforcement. As originally designed the cantilevers would not have held their own weight.[9]

The contractor, Walter Hall, who was also an engineer, produced independent computations and argued for increasing the reinforcement. Wright rebuffed the contractor and Kaufmann took Wright's advice. Wright's team did not update their design. Nevertheless, the contractor quietly doubled the amount of reinforcement in these.[9] Even this was not enough, but likely prevented the structure's collapse.

The 2002 repair scheme involved temporarily supporting the structure; careful, selective, removal of the floor; post-tensioning the cantilevers underneath the floor; then restoring the finished floor.[9]

Given the humid environment directly over running water, the house also had mold problems. The senior Mr. Kaufmann called Fallingwater "a seven-bucket building" for its leaks, and nicknamed it "Rising Mildew" (Brand 1995).

References

- ^ "Usonian Architech". TIME magazine Jan. 17, 1938. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine - Travel - Fallingwater". Smithsonian magazine January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine - Travel - The Smithsonian Life List". Smithsonian magazine January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ Bob Vila (1996). ""Guide to Historic Homes of America."" (html). A&E Network.

- ^ "[W]hy did the client say that he expected to look from his house toward the waterfall rather than dwell above it?" Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House, New York: Abbeville Press, p. 31. (ISBN 0-89659-662-1)

- ^ a b Plushnick-Masti, Ramit (2007-09-27). "New Wright house in western Pa. completes trinity of work". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Silman, Robert and John Matteo (2001-07-01). "Repair and Retrofit: Is Falling Water Falling Down?" (PDF). Structure Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ Toker, Franklin (2003). Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's Most Extraordinary House. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4026-4.

- ^ a b c Feldman, Gerard C. (2005). "Fallingwater Is No Longer Falling". STRUCTURE magazine (September): pp. 46–50.

- Trapp, Frank (1987). Peter Blume. Rizzoli, New York.

- Hoffmann, Donald (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater: The House and Its History (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27430-6.

- Brand, Stewart (1995). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013996-6.

- McCarter, Robert (2002). Fallingwater Aid (Architecture in Detail). Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4213-3.

External links

- Official website - includes visiting information

- Information and photographs of Fallingwater

- Photo Visit of Fallingwater

- Fallingwater architectural review

- 3D Virtual Model of Fallingwater

- YouTube video walkthru of Fallingwater

Template:Geolinks-US-buildingscale

- http://www.mocpages.com/moc.php/31871 LEGO Fallingwater