Afrocentrism: Difference between revisions

→Cranial analysis and forensic reconstruction of mummified remains: replaced unverified interview with verified Washington Post interview |

|||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

In an press release dated May 10, 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities reported, "Based on this skull, the American and French teams both concluded that the subject was Caucasoid (the type of human typically found, for example, in North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East)." [http://ftp2.nationalgeographic.com/pressroom/TUT_Reconstruction/Press_Materials/Egypt_Press_Release.doc] |

In an press release dated May 10, 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities reported, "Based on this skull, the American and French teams both concluded that the subject was Caucasoid (the type of human typically found, for example, in North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East)." [http://ftp2.nationalgeographic.com/pressroom/TUT_Reconstruction/Press_Materials/Egypt_Press_Release.doc] |

||

In a telephone interview with the Washington Post, Susan Antón, a member of the American team, described the specimen as "somewhat equivocal." "The decidedly masculine jaw was the giveaway, she said, although the rounded forehead, the sharp brow and the prominent eyes suggested a woman. Age was easy, she said. The third molars were in the process of coming in, something that happens between the ages of 18 and 20. Race was "the hardest call." The shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils — a European characteristic. The skull was a North African." [http://www.chron.com/cs/CDA/ssistory.mpl/nation/3176462] |

|||

However, in the words of Susan Antón, a member of the American team, "Our group did not, in fact, find Tut to be a 'Caucasoid North African.' We classified him as African based on many of the [skull's facio-cranial] features...." Antón noted that this was done regardless of the fact that the nasal cavity was relatively narrow, because the metrics were within the range of probability for the Nilotic peoples of the region. With regard to any finding of European origins, Antón commented that, in light of the cumulative evidence, she "determined the statistical association [with Europeans] was very low and, therefore, based on the nonmetric characters, was not likely to be accurate." "... it would have been less confusing," Antón added, "if that terminology ['Caucasoid North African'] had not been used." "I think his features are consistent with him being African." |

|||

Antón refused, however, to assign a specific racial designation to the specimen, citing inherent problems with the concept of race. |

Antón refused, however, to assign a specific racial designation to the specimen, citing inherent problems with the concept of race. [http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/41131000/jpg/_41131803_afp203bodywhite.jpg] |

||

===Ethnographic murals of the New Kingdom=== |

===Ethnographic murals of the New Kingdom=== |

||

Revision as of 12:15, 15 July 2005

Afrocentrism is a worldview or perspective that is centered on Africa and blacks. Afrocentric scholars typically claim that Western accounts of world history and civilization have neglected or systematically denied the contributions of indigenous, black African peoples. The term "Afrocentrism" thus implies a perspective which is in diametric opposition to that of Eurocentrism. However, it also often functions to distinguish the influence in Africa of Arab, European and Asian peoples from indigenous African achievements. This particular emphasis on Africa is historically tied to black civil rights movements and anti-imperialist ideologies in America and the Caribbean. In modern America, it is associated with African-centred education policies that purport to be anti-racist.

Central to Afrocentrism is the fundamental reorientation of historical scholarship. Afrocentrism shifts the study and evaluation of world history and civilization from a traditionally Western, Eurocentric paradigm — that is, one which treats primarily white or European contributions and posits Greco-Roman beginnings of Western civilization — to one that treats primarily black Africa and black contributions and posits black Egyptian beginnings of Western civilization.

Afrocentrists claim that early dynastic Egypt was a black civilization. Geopolitical issues generally have caused Egypt to be considered part of the Middle East; however, geographically, Egypt is located squarely within the African continent. Afrocentrists argue that salient cultural characteristics of ancient dynastic Egypt are indigenous to Africa and that these features are present in other African civilizations. In addition, they believe the study of ancient Egyptian culture should emphasise connections to other early African civilizations such as Kerma and the Meroitic civilizations of Nubia, as archaeology clearly indicates the interrelatedness of Nilotic cultures with dynastic Egypt. Afrocentrists claim that these made important contributions to ancient Greek and Roman civilizations that traditionally have been either overlooked or appropriated by the West. The more common belief, however, is that ancient Egyptian civilization is more closely associated with the civilizations of the Mediterranean region and Fertile Crescent than with the rest of Africa.

Afrocentrism finds itself in direct opposition to the views of mainstream scholars such as British historian Arnold Toynbee, who regarded the ancient Egyptian cultural sphere as having died out without leaving a successor and who derided as a "myth" the idea that Egypt was the "origin of Western civilization." However, there are numerous accounts in the historical record dating back several centuries wherein scholars have written of Egypt's contributions to Mediterranean civilizations and of black-skinned, "Negroid" Egyptians. More recently, Afrocentrism has found sympathetic readings from mainstream scholars such as Martin Bernal.

Afrocentrism has been charged by one prominent critic as being "a mythology that is racist, reactionary, and essentially therapeutic." Afrocentrists, however, level similar charges at what they perceive as a pronounced Eurocentrism in mainstream historical works, countering that the Afrocentrist approach merely attempts to set the historical record straight by overturning a false paradigm, the basis of which is scholarship often slanted by conscious or unconscious racist attitudes.

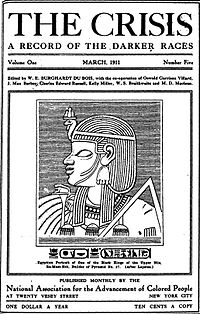

History of Afrocentrism

The beginnings of Afrocentric scholarship can be found in the work of African-American and Caribbean intellectuals early in the twentieth century. Publications such as The Crisis and the Journal of Negro History sought to counter the prevailing view in the West that Africa had contributed nothing to human cultural history that was not the result of incursions by Europeans and Arabs. These journals sought to stress the blackness of some Egyptian pharaohs and to investigate Sub-Saharan African history. The editor of The Crisis W.E.B. DuBois went on to research West African culture and to attempt to construct a pan-Africanist value system based on West African traditions. DuBois later became editor of the Encyclopedia Africana. Some aspects of DuBois's approach is evidenced in the work of the Senegalese anthopologist Cheikh Anta Diop, who claimed to have identified a pan-African language and to have proved that ancient Egyptians were indeed black-skinned.

However, Diop also drew on the ideas of George M. James, a follower of the black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey, who emphasised the importance of Ethiopia as a great black civilization and who argued that black peoples should develop pride in African history. James's book Stolen Legacy (1954) is often cited as one of the foundational texts of modern Afrocentrism. James claimed that Greek philosophy was "stolen" from Ancient Egyptian mystery traditions and that these had developed from distinctively African cultural roots. For James, the works of Aristotle and other Greek thinkers were in fact poor synopses of some aspects of Ancient Egyptian wisdom. The Greeks were violent and quarrelsome people, unlike the Egyptians, and were not naturally capable of philosophy.

These ideas were not wholly new, but date back to eighteenth century Masonic texts that drew on ancient writings that claimed Greek thinkers studied in Egypt. The poet William Blake had also attacked "the stolen and perverted writings of Homer and Ovid, of Plato and Cicero," asserting that they were copies of more ancient Semitic wisdom. Such views were associated with radical and Romantic thought that rejected classical Greco-Roman culture as the model for civilization. James's distinct contribution was to tie these claims to an opposition between white European and black African identity, associating these alleged ancient appropriations of black wisdom with white imperialist exploitation of black peoples and thefts of artifacts from black African cultures. By claiming that the Greeks were barbaric and were innately incapable of philosophy, he also inverted normative imperialist racial hierarchies, which made the same claims about black Africans.

James's approach was copied by a number of other writers and has had an influence on many books that claim to prove that black Africans originated intellectual or technological achievements that were later claimed by whites. Some of these books are not considered to be serious scholarship. However, several later writers have abandoned James's more extreme claims to concentrate on the notion that modern black peoples should center their understanding of culture and history on Africa. The most influential of these writers is Molefi Kete Asante, whose book Afrocentricity (1988) directly connected Afrocentrism to radical black civil-rights politics, arguing that African Americans should look to African cultures "as a critical corrective to a displaced agency among Africans."

Other authors have adapted James's assertion that Egyptian culture's influence on the Greeks has been underestimated. Among such scholars the most influential is Martin Bernal, whose book Black Athena stressed influence of what he called Afroasiatic and Semitic civilizations on the classical ones. Yet other writers have abandoned the claim that Europeans stole African culture, but concentrate on the study of indigenous African civilizations and peoples as a corrective to emphasis on European and Arabic influence on the continent. Such Afrocentric scholars maintain that a paradigm shift from a view of world history centered around European accomplishments and racist assumptions about other peoples and cultures to one that emphasizes the black beginnings of humankind and black contributions to world history, would result in significant attitudinal shifts in the West and elsewhere. Indeed, many claim that a dramatic shift has already occurred. This, then, they argue, challenges the Eurocentric view of world history which for so many centuries devalued and appropriated, or simply ignored achievements by blacks.

Criticisms of Afrocentrism

Critics of Afrocentrism counter that much historical Afrocentric research simply lacks scientific merit and that it actually seeks to supplant and counter one form of racism with another, rather than attempt to arrive at the truth. Among scholarly critics, Mary Lefkowitz's Not out of Africa is widely regarded as the foremost critical work. In it, she contends Afrocentric historical claims are grounded in identity politics and myth rather than sound scholarship. Like most other classical scholars, she rejects James's views on the ground that his sources predate the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Actual ancient Egyptian texts show little similarity to Greek philosophy. She also contends that Bernal underestimates the distinctiveness of Greek intellectual culture. Asante, however, disputes her conclusions.

Afrocentrists tend to emphasise the racial and cultural unity of Africa as a whole as the home of black, or "Negroid" peoples. However, critics assert that Afrocentrism relies on a projection of modern racial and geographical categories onto ancient cultures in which they simply did not exist. It is argued that in ancient Western culture, the distinction between Europe and Africa was not as important as the notion that civilized peoples encircled the Mediterranean sea. The farther from the Mediterranean they were, the more alien they were considered to be. This applied to all peoples. The equation of "African" with black identity has also been criticized, partly because movement of populations around the Mediterranean in ancient times makes any rigid distinctions among North African, Asian, and European peoples of the area problematic; and partly because the notion of a unified "black" or Negroid race is itself considered to be unsustainable by many modern geneticists. Further, Diop's claim to have discovered a pan-African proto-language is rejected by almost all linguists.

People think of themselves as belonging to races defined by skin color and physiognomy and link this to their ancestry. One of the impacts of this is that historical achievements are ascribed to races with which modern peoples identify themselves. Others insist that this approach violates the fundamental demand of history as a discipline, which should aspire to understand events as they occurred, not as they affect the self-esteem of modern people.

Afrocentrists, however, contend that race as a social and political construct still exists. They argue that the racist untruths propounded for centuries– that blacks had no civilization, no written language, no culture and no history of any note before coming into contact with Europeans– make the racial identity of ancient Egypt an important issue. Further, such lies have been applied to a particular, broad category of humanity based on the same "racial" phenotype and lineages used by Afrocentrists in refuting such myths. However artificial and discredited a construct, the matter of race became an important and enduring issue, Afrocentrists argue, when whites and others pronounced an entire segment of humanity inherently inferior on the basis of it. Further, such biases still exist today. As a result, Afrocentrists contend, it is important to set the historical record straight within the context in which the history of human civilizations heretofore has been framed, taught and studied— and that is the context of race.

Crucial to this aspect of the debate are arguments about whether the ancient Egyptians reasonably can be considered to have been black and the extent of significant cultural or racial links between sub-Saharan and nonblack North African peoples.

Egypt and Black Identity

Many Afrocentrists insist that ancient Egyptians were black African peoples, often emphasising that this black identity was strongest in early Egyptian history, but waxed and waned over time. Among Afrocentrist authors, it is common to refer to Egypt as "Kemet," the indigenous term for the country, which means "black land." Traditionally, mainstream scholars contend this term refers to the dark, fertile soil beside the Nile, in contrast to the desert beyond it, labelled the "red land" by Egyptians. Afrocentrists, however, associate the term with Egyptian racial identity, pointing out that ancient Egyptians also called themselves "Kmemeu," or "the black people" and their subjects "Kemetu," or "the blacks' people." They also cite the archaeological evidence, particularly that of temple statuary, and the writings of Herodotus and other ancient authors, who refer to the dark skin and woolly hair of Egyptians. Opponents would argue that indigenous Egyptian terminology is best translated as "people of the black land," and that Western classical writers usually described Egyptians as a mid-tone between black Ethiopians and pale Europeans. Herodotus himself is clear that Egyptians look different from Ethiopians. Marcus Manilius states that "the Ethiopians stain the world and depict a race of men steeped in darkness. Less sun-burnt are the natives of India. The land of Egypt, flooded by the Nile, darkens bodies more mildly owing to the inundation of its fields: it is a country nearer to us and its moderate climate imparts a medium tone."

Both Afrocentrists and mainstream scholars typically connect the ancient Egyptian language with those of various other African peoples. However, most linguists consider Egyptian a typical example of an Afro-Asiatic (otherwise called "Hamito-Semitic") language - a language group, most probably native to Africa, that covers North Africa, the Horn of Africa, much of Chad and Nigeria, and most of the Middle East. As a result, speakers of Afro-Asiatic languages are multi-ethnic and possess a wide range of skin colors. In contrast, Afrocentrists commonly link ancient Egyptian with languages of the Niger-Congo family, virtually all the speakers of which are blacks. For example, Diop claims that the ancient Egyptian language has vocabulary in common with Wolof, while Théophile Obenga links it with Mbochi, both of which are Niger-Congo languages. However, mainstream scholars contend it is inadequate to list similar-sounding or possibly related terms in different languages; only a rigorous investigation using the methodology of historical linguistics, in particular the comparative method, suffices.

Afrocentrists also cite the results of Diop's forensic tests of melanin content in Egyptian mummies and of forensic reconstruction of skulls to prove their contention that the early dynastic Egyptians were black Africans and remained so in predominant part for millennia. Opponents question the validity of Diop's tests, contending that reliable evidence about melanin levels cannot be easily extracted from mummies because of the chemical treatment to which they have been subjected. Likewise, reconstructions of faces from skulls relies on assumptions concerning ethnicity, and such results as have been obtained are ambiguous. However, supporters of Diop's claims assert that similar tests for determining the melanin content in bones have been used by police departments in the gathering of forensic evidence around the world.

Opponents of Afrocentrism often argue that Egyptians belong among the Semitic peoples of the Middle-East, pointing to the fact that Egypt is at the extreme north eastern edge of the African continent, close to both Israel and Arabia. However, rather than being comprised of a singular people, Egypt also extends south into areas occupied by undeniably black-skinned people. Further, "Semitic" also defines a language group that also includes many black African peoples.

It is commonly accepted that the population of Egypt was, at least in later dynasties, a mixture of black African; Mediterranean; Semitic; and, even later, European peoples. However, these very categories are disputable and indeterminate. In typical portrayals of Egyptians in their own art, from the Old Kingdom onwards they appear as brown-skinned (using a red ochre pigment). The tomb of Tutankhamun contained a box on which the king was depicted riding a chariot over black-skinned people, presumably representing Nubia. There were also walking sticks, the handles of which depicted both black-skinned and pale-skinned conquered adversaries, representing defeated Nubian and Asiatic enemies. Sometimes, such depictions of skin tones were symbolic, and the details of this imagery have yet to be fully explained.

However, skin color among various populations of indigenous Africans differs naturally. Today, a brown-skinned Fula is generally considered no less a black African than a very dark-skinned Nubian. Afrocentrists argue that the same can be said of Nubians and Egyptians. There are numerous representations in Egyptian sculpture and murals spanning more than three millennia of individuals with dark skin, of faces which are broad across the cheekbones, with full lips and pronounced prognathisms. In fact, the Great Sphinx of Giza (above left) clearly exhibits these same characteristics. Such features are characteristic of a "Negroid" phenotype. In fact, prognathism— a forward-slanting facial profile— is a key indicator used by forensic experts today to determine racial identity. It is important to note, however, that all aspects of the standard Negroid phenotype of coarse, curly hair; broad, flat noses and full lips do not apply to all black peoples, many of whom have relatively straight hair and narrower facial features. Paradoxically, while these peoples posses a range of skin tones and some diverge from the classically Negroid phenotype, they are considered no less "Negro," no less black, than other autochthonous peoples of the African continent— the Nilotic peoples of northeast and East Africa being an example. Further, these indigenous, black, African peoples of the Nile Valley all comprised in part— and Afrocentrists believe in predominant part— the ethnically diverse kingdoms of ancient dynastic Egypt.

Cranial analysis and forensic reconstruction of mummified remains

The ancient Egyptians themselves traced their origin to a land they called "Punt," [1], or "Ta Nteru" ("Land of the Gods"). Scholars once commonly thought Punt was located on what is today the Somali coast, but it is now thought to have been in either southern Sudan or Eritrea. The ancient Puntites commonly were described as black peoples with "Negroid" features and elongated, or dolichocephalic, heads. In fact, an elongated skull is not at all atypical among black African populations of the region, and their skulls are typically significantly longer than those of Caucasians. Some Nordic populations also are known to have long heads; however, a Nordic presence in the Nile Valley in prehistoric times is implausible.

Wrote historian Drusilla Houston in her 1926 work The Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire:

Strabo mentions the Nubians as a great race west of the Nile. They came originally from Kordofan, whence they emigrated two thousand years ago. They have rejected the name Nubas as it has become synonymous with slave. They call themselves Barabra, their ancient race name. Sanskrit historians call the Old Race of the Upper Nile Barabra. These Nubians have become slightly modified but are still plainly Negroid. They look like the Wawa on the Egyptian monuments. The Retu type number one was the ancient Egyptian, the Retu type number two was in feature an intermingling of the Ethiopian and Egyptian types. The Wawa were Cushites and the name occurs in the mural inscriptions five thousands years ago.[2]

1500 years after the founding of the first dynasty and after centuries of miscegenation of the population of Egypt among various ethnic groups, Tutankhamun's father and others of the 18th dynasty show facial similarities to Negroid, black Africans (see image of Queen Tiye above). Documentaries in 2002 and 2003 aired on the Discovery Channel in the U.S. provided strikingly black, Negroid images of both Tutankhamun[3] and Nefertiti[4] based on forensic reconstruction of mummified remains. However, more recent forensic reconstructions of Tutankhamun, produced a somewhat different result.[5]

An interesting aspect of the recent reconstructions is their somewhat bucktoothed appearance. This form of prognathism is a trademark physical characteristic of many Sudanese and other Nilotic peoples of the region. An 1870 edition of the Journal of the Ethnological Society of London describes in detail the "Australian," or Australoid (commonly today called native Australian or native Bornean), peoples of the Australian continent and the interior of the Deccan:

The males of this type are commonly of fair stature, with well-developed torso and arms, but relatively and absolutely slender legs. The colour of the skin is some shade of chocolate-brown; and the eyes are very dark brown, or black. The hair is usually raven-black, fine and silky in texture; and it is never woolly, but usually wavy and tolerably long. The beard is sometimes well developed, as is the hair upon the body and the eyebrows. The Australians are invariably dolichocephalic, the cranial index rarely exceeding 75 or 76, and often not amounting to more than 71 or 72. The brow-ridges are strong and prominent, though the frontal sinuses are in general very small or absent. The norma occipitalis is usually sharply pentagonal. The nose is broad rather than flat; the jaws are heavy, and the lips remarkably coarse and flexible. There is usually strongly marked alveolar prognathism. The teeth are large, and the fangs usually stronger and more distinctly marked than in other forms of mankind. The outlet of the male pelvis is remarkably narrow. These characters are common to all the inhabitants of Australia proper (excluding Tasmania); and the only notable differences I have observed are that, in some Australians, the calvaria is high and wall-sided, while in others it is remarkably depressed. No skulls are, in general, so easily recognizable as fair examples of those of the Australians, though those of their nearest neighbours, the inhabitants of the Negrito Islands, are frequently hardly distinguishable from them. The only people out of Australia who present the chief characteristics of the Australians in a well-marked form are the so-called hill-tribes who inhabit the interior of the Dekhan, in Hindostan. [6].

The accompanying map in the journal article places these "Australian" peoples in the Nile Valley, India and Australia, which is in keeping with patterns of migragtion and settlement well documented in ancient texts and oral histories, as well as supported in part by the modern DNA evidence of geneticist Spencer Wells. (See "Black-centered history and Africa" below.)

Scientific examination and analysis of skulls of royal Egyptian mummies across several dynasties confirm a predominance over time of sloping and dolichocephalic cranial structures and/or significant alveolar prognathisms and receding chins. Further, these characteristics, common to "mesolithic Nubians" as well as modern-day Nubians,[7] were prominent features in royal mummies of the late 17th and 18th Dynasties: Queen Ahmes-Nefertari, Amenhotep I, Queen Meryetamon, Thutmose I, Thutmose II, Tjuya (Queen Tiye's mother), and an "Elder Lady" thought likely to be Queen Tiye among them.[8] The controversial fair skin and hazel eyes of the Egyptian team's reconstruction of King Tutankhamun notwithstanding, Tutankhamun's alveolar prognathism, receding chin and dolichocephalic cranium [9] evidence extremely strong Nilotic— that is to say, black African— characteristics. [10] In fact, according to facio-cranial analysis, King Tutankhamun shared precisely the same distinctive racial characteristics as his fellow royals of the 17th and 18th Dynasties noted above.

In the most recent attempt to put a face on the long-dead monarch, three separate teams of Egyptian, French and American investigators each produced a reconstruction of what they determined to be an accurate likeness of King Tutankhamun. The Egyptian and French teams knew the identity of the subject whose face they were reconstructing, the Egyptians working from CT scans of the skull itself, the French and American teams working from identical plastic reproductions. The American team, however, did not know the identity of the specimen. According to widely publicized press reports, Zahi Hawass of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), announced that Tutankhamun was identified "correctly" as a "Caucasoid North African." Many argue, however, that the actual death mask of King Tutankhamun appears strikingly Negroid rather than Caucasoid.[11]

The Egyptian team's "Caucasoid" reconstruction, which has been exhibited prominently as the "real" image of King Tutankhamun, has sparked considerable criticism. Afrocentrists have criticized the Egyptian team's decision to arbitrarily assign pale skin and hazel eyes to the young king based on modern-day, highly miscegenated, Arabized Egyptians of present-day Egypt, features which they contend do not properly reflect the eye or skin color of the average citizen of ancient dynastic Egypt, or of today's rural Egypt. Other Afrocentrists have argued that even mummy portraits of presumably highly miscegenated Egyptian subjects of the Roman era nearly 1,500 years after Tutankhamun's death reflect a blacker, more Afro-Semitic-looking Egyptian populace than is represented by the Egyptian reconstruction.[12]

In an press release dated May 10, 2005, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities reported, "Based on this skull, the American and French teams both concluded that the subject was Caucasoid (the type of human typically found, for example, in North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East)." [13]

In a telephone interview with the Washington Post, Susan Antón, a member of the American team, described the specimen as "somewhat equivocal." "The decidedly masculine jaw was the giveaway, she said, although the rounded forehead, the sharp brow and the prominent eyes suggested a woman. Age was easy, she said. The third molars were in the process of coming in, something that happens between the ages of 18 and 20. Race was "the hardest call." The shape of the cranial cavity indicated an African, while the nose opening suggested narrow nostrils — a European characteristic. The skull was a North African." [14]

Antón refused, however, to assign a specific racial designation to the specimen, citing inherent problems with the concept of race. [15]

Ethnographic murals of the New Kingdom

There are numerous other images in which Egyptians are contrasted with non-Egyptian peoples. Like other peoples throughout history, the Egyptians seem to have identified themselves as an ideal or norm of sorts among other populations. Further, there is evidence the ancient Egyptians thought in terms of national identity and ethnicity; the modern Western concept of "race" was alien to them. During the New Kingdom, Egyptian suzerainty extended to the north as far as the Hittite empire and into Nubia to the south. At this time, Egyptian sacred literature and imagery commented systematically on differences based on these two criteria. This is evident in Akhenaton's "Great Hymn to the Aten", in which it is said that the peoples of the world are differented by God: "Their tongues are separate in speech/And their natures as well;/ Their skins are distinguished./The countries of Syria and Nubia, the land of Egypt,/ You set every man in his place."

This differentiation of peoples is later refined in the Book of Gates, a sacred text that describes the passage of the soul though the underworld. This contains a description of the distinct peoples known to the Egyptians: Egyptians themselves, plus Asiatics, Nubians and Libyans. These peoples are illustrated in several tomb decorations, in which they are differentiated by skin-color and clothing. These depict Egyptians ("Ret," or "men," often used as "ret na romé," meaning "we men above mankind"); Asiatics/Semites ("AAMW" or "Namu,": "travelers" or "wanderers," often used as "namu sho," or "people who travel the sands," meaning nomads or Bedu/Bedouin); other Africans ("Nahasu," or "strangers"); and, finally, Libyans, ("TMHHW", or Tamhu," a term for which several etymologies have been proposed). In most cases the Egyptians are depicted as red-brown, wearing loincloths. Uniquely, in the tomb of Ramesses III a label identifies figures identical to Nubians as Egyptians. Quite strikingly, these images of the Ret and the Nahasu are identical in every way, including dress. Afrocentrists use this as evidence that Egyptians were identical to other Africans. Other Egyptologists take the view that the artists mislabelled the images because the labels are reversed for TMHHW (Libyans) and AAMW (Asiatics/Semites) as well.

Black-centered history and Africa

The relationship among racial, cultural and continental identities is one of the more difficult problems in Afrocentic thought. Despite the problems with a Eurocentric approach to history, there has been a common European cultural identity for many centuries. It is more difficult to make the same claim for Africa, in which diverse cultures often were unaware of one another's existence. For this reason, some Afrocentrists have been accused of manufacturing "African" cultural values by cherry-picking from wholly different peoples.

In other instances, the concept of black racial identity has been used to include among "African" peoples populations generally thought of as non-Africans, such as the Australoid (sometimes called "Veddoid") peoples of Australia and New Guinea and the Tamils (also called Dravidians) of India and the people of the rest of the Indian subcontinent. Also included in the African diaspora are the Negroid, aboriginal peoples of the Far East (Thailand, Java, Borneo, Sumatra and Malaysia, Vietnam and Cambodia); Melanesia, Micronesia andPolynesia; and, speculatively, the Olmecs of what is now Mexico.[16] Afrocentrists who adopt this approach contend that such peoples are African in a racial sense, just as non-aboriginal inhabitants of Australia may be said to be European. Critics would argue that such peoples were not recent emigrants from Africa, and the entire population of the world might just as reasonably be considered part of an African race according to the Out of Africa model of human migration. Studies show that these darker-skinned ethic groups— with the exception, of course, of the Olmecs— and "Mongoloid" East Asians are genetically closer to one another than they are to indigenous Africans. However, Afrocentrists point out that such genetic similarities are due to populations of blacks and later Asiatic peoples developing together in isolation over time. This fact, they contend, does not change the fundamental black racial identity of these peoples based on the traditional metrics of the classic "Negroid" phenotype, physical similarities with other peoples classified as Negroid and presumptive patterns of prehistoric migrations. In such matters, Afrocentrists adopt the pan-Africanist perspective that such peoples are all "African people" or "diasporic Africans." As Afrocentric scholar Runoko Rashidi writes, they are all part of the "global African community."

Interestingly, in 2002, geneticist Spencer Wells completed a study of human out-migrations from Africa utilizing the DNA of San Bushmen of the Kalahari who, according to Wells, have the oldest human DNA on earth. Wells concluded from analysis of DNA specimens that the earliest human emigration from Africa of which there is definitive proof was that of San Bushmen to southern India (the modern Tamils) and then along coastal routes to Australia (the Aborigines), while shortly afterwards a second migration from Africa, also by San Bushmen, reached Central Asia, and thence covered most of the Eurasian continent.

A different world-view

I am apt to suspect the Negroes...to be naturally inferior to the White. There never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white.... — David Hume, 18th century European philosopher

When we classify mankind by color, the only one of the primary races...which has not made a creative contribution to any of our twenty-one civilizations is the black race. — Arnold J. Toynbee, 19th century historian

A Black skin means membership in a race of men which has never created a civilization of any kind. — John Burgess, 19th century scholar[17]

Afrocentrists argue that the ignorance and blatant racism of such mainstream scholars and historians, as well as what they consider to be the attendant appropriation or "whitewashing" of black history, make the study of world history with new eyes an important undertaking. It is in this sense that the Afrocentrist paradigm legitimately may be considered to be "therapeutic." That is not to say, however, that it is necessarily, as Lefkowitz has charged, "an excuse to teach myth as history."

While their findings may be sometimes tentative and often controversial, Afrocentrist scholars do not approach Afrocentrism as artful storytelling or pseudo-social science. It is neither fiction nor mere sophistry. In their eyes, Afrocentrism is a critical, historiographical approach to history, based on a weltanschauung which is fundamentally and radically different from that of many of their relatively recent, mainstream predecessors; but which harkens back to an earlier view of the history of world civilizations. It is the examination and analysis of existing scholarship, as well as the study of the original historical record itself, grounded in scholarly inquiry and rigorous research.

List of notable Afrocentric historians

- Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, professor, author: Afrocentricity: The theory of Social Change; The Afrocentric Idea; The Egyptian Philosophers: Ancient African Voices from Imhotep to Akhenaten

- Dr. Ishakamusa Barashango, college professor and lecturer; founder, Temple of the Black Messiah, School of History and Religion; co-founder and creative director, Fourth Dynasty Publishing Company, Silver Spring, Maryland

- Dr. Jacob Carruthers, Egyptologist; founding director of the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilization; founder and director of the Kemetic Institute, Chicago

- Dr. Cheikh Anta Diop[18],[19], author: The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality; Civilization or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology; Precolonial Black Africa; The Cultural Unity of Black Africa: The Domains of Patriarchy and of Matriarchy in Classical Antiquity; The Peopling of Ancient Egypt & the Deciphering of the Meroitic Script

- Dr. H.B. ("Barry") Fell, Harvard professor, linguist, author: Saga America, 1980 [20]

- Drusilla Dunjee Houston, lecturer, syndicated columnist, author: Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, 1926.

- Dr. Yosef Ben-Jochannan, author: African Origins of Major "Western Religions"; Black Man of the Nile and His Family; Africa: Mother of Western Civilization; New Dimensions in African History; The Myth of Exodus and Genesis and the Exclusion of Their African Origins; Africa: Mother of Western Civilization; Abu Simbel to Ghizeh: A Guide Book and Manual

- Dr. Runoko Rashidi[21], author: Introduction to African Civilizations; The global African community: The African presence in Asia, Australia, and the South Pacific

- J.A. Rogers, author: Sex and Race: Negro-Caucasian Mixing in All Ages and All Lands : The Old World; Nature Knows No Color Line; Sex and Race: A History of White, Negro, and Indian Miscegenation in the Two Americas : The New World; 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro With Complete Proof: A Short Cut to the World History of the Negro

- Dr. Ivan van Sertima, author: They Came before Columbus: The African Presence in Ancient Amerca, African Presence in Early Europe; Blacks in Science Acient and Modern; African Presence in Early Asia; African Presence in Early America; Early America Revisited; Egypt Revisited: Journal of African Civilizations; Nile Valley Civilizations; Egypt: Child of Africa (Journal of African Civilizations, V. 12); The Golden Age of the Moor (Journal of African Civilizations, Vol. 11, Fall 1991); Great Black Leaders: Ancient and Modern; Great African Thinkers: Cheikh Anta Diop[22]

- Dr. Chancellor Williams, author: The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race from 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D.

- Dr. Théophile Obenga, author: Ancient Egypt and Black Africa : a student's handbook for the study of Ancient Egypt in philosophy, linguistics, and gender relations

- Dr. Asa Hilliard, III, author: SBA: The Reawakening of the African Mind; The Teachings of Ptahhotep

Related topics

External Links

- African by Nature Presents Your Eyes, an examination of black African identity vs. Europeanized images of Egypt

- Afrocentrism from The Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll

- Afrocentrism: The Argument We're Really Having by Ibrahim Sundiata

- Afrocentrism in Rastafari

- Afrocentrist multicultural pseudo-history by The Association for Rational Thought

- Building Bridges to Afrocentrism by Ann Macy Roth, for the University of Pennsylvania's African Studies Center

- "The Egyptians: Who Were They?"

- "Egyptology: Hanging in the Hair," by Anu M'bantu and Fari Supia, West Africa Magazine, July 8, 2001

- Fallacies of Afrocentrism by Grover Furr, for the Montclair State University

- "The Global African Presence," by Runoko Rashidi

- "Negro History and The Myth of Ham's Curse," by Babu G. Ranganathan (an East Indian writes of the black identity of ancient Egypt, India, etc.)

- Pride and prejudice By Dinesh D'Souza

- "Race in Antiquity: Truly Out of Africa," by Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, a critical assessment of Lefkowitz's Not Out of Africa.

- Racism and the Rediscovery of Ancient Nubia

- "Return to Glory," The Freeman Institute

- Safari Scholarship Reinvents History by Ilana Mercer

- UC Davis History Professor Clarence Walker's take on Afrocentrism

References

- Asante, Molefi Kete. Kemet, Afrocentricity, and knowledge. Africa World Press, 1990).

- Bailey, Randall C (ed.). Yet with a steady beat: contemporary U.S. Afrocentric biblical interpretation (Society of Biblical Literature, 2003).

- Berlinerblau, Jacques. Heresy in the University: The Black Athena Controversy and the Responsibilities of American Intellectuals (Rutgers University Press, 1999)

- Binder, Amy J. Contentious curricula : Afrocentrism and creationism in American public schools (Princeton University Press, 2002).

- Browder, Anthony T. Nile Valley Contributions To Civilization: Exploding the Myths, Volume 1. (Washington, DC: Institute of Karmic Guidance, 1992).

- Crawford, Clinton. Recasting Ancient Egypt In The African Context: Toward A Model Curriculum Using Art And Language. (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press, 1996.

- Henderson, Errol Anthony. Afrocentrism and world politics: towards a new paradigm (Praeger, Westport, Conn., 1995).

- Henke, Holger and Reno, Fred (eds.). Modern political culture in the Caribbean (University of the West Indies Press, 2003).

- Howe, Stephen. Afrocentrism: mythical pasts and imagined homes (Verso, London, 1998).

- Houston, Drusilla Dunjee. Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire (Universal Publishing Co.: Oklahoma City, 1926).

- Kershaw, Terry. "Afrocentrism and the Afrocentric method." Western Journal of Black Studies, 1992, 16(3), pp 160-168.

- Lefkowitz, Mary R. Not out of Africa: how Afrocentrism became an excuse to teach myth as history (BasicBooks, NY, c1996).

- Lewis, Martin W. The myth of continents: a critique of metageography (University of California Press, 1997).

- Magida, Arthur J. Prophet of rage a life of Louis Farrakhan and his nation (BasicBooks, NY, 1996).

- Moses, Wilson Jeremiah. Afrotopia: the roots of African American popular history (Cambridge University Press, 1998).

- Sniderman, Paul M. and Piazza, Thomas. Black pride and black prejudice (Princeton University Press, 2002).

- Spivey, Donald. Fire from the soul: a history of the African-American struggle (Carolina Academic Press, 2003).

- Walker, Clarence E. We Can't Go Home Again: An Argument about Afrocentrism (Oxford University Press, 2000).

- Wells, Spencer. The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey (Princeton University Press, 2002).