Serotonin transporter: Difference between revisions

Cite Huang & Santangelo 2008 finding no significant association between autism and 5-HTTLPR or STin2 VNTR. |

m + ja: |

||

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

[[Category:Neurotransmitter transporters]] |

[[Category:Neurotransmitter transporters]] |

||

[[Category:Solute carrier family]] |

[[Category:Solute carrier family]] |

||

[[ja:セロトニントランスポーター遺伝子]] |

|||

Revision as of 07:45, 27 February 2008

The serotonin transporter (SERT) is a monoamine transporter protein. Template:PBB Summary

Function

It reuptakes serotonin in synaptic cleft and terminate its function. It allows neurons, platelets, and other cells to accumulate the chemical neurotransmitter serotonin, which affects emotions and drives.

Neurons communicate by using chemical messages like serotonin between cells. The transporter protein, by recycling serotonin, regulates its concentration in a gap, or synapse, and thus its effects on a receiving neuron’s receptor.

Medical studies have shown that changes in serotonin transporter metabolism appear to be associated with many different phenomena, including alcoholism, clinical depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), romantic love[5] and hypertension.

Pharmacology

SERT spans the plasma membrane 12 times. It belongs to NE, DA, SERT monoamine transporter family. Transporters are important sites for agents that treat psychiatric disorders. Drugs that reduce the binding of serotonin to transporters (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs) are used to treat mental disorders. About half of patients with OCD are treated with SSRIs. Fluoxetine is an example of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Genetics

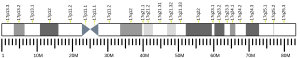

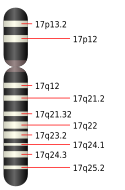

The gene that encodes the serotonin transporter is called solute carrier family 6 neurotransmitter transporter, serotonin), member 4 (SLC6A4). (See Solute carrier family). In humans the gene is found on chromosome 17 on location 17q11.1–q12.[6]

Mutations associated with the gene may result in changes in serotonin transporter function, and experiments with mice have identified more the 50 different phenotypic changes as a result of genetic variation. These phenotypic changes may, e.g., be increased anxiety and gut dysfunction.[7] Some of the genetic variations associated with the gene are:[7]

- Length variation in the serotonin-transporter-gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR)

- rs25531 — a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the 5-HTTLPR

- rs25532 — another SNP in the 5-HTTLPR

- STin2 — a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) in the functional intron 2

- G56A on the second exon

- I425V on the ninth exon

Length variation in 5-HTTLPR

The promotor region of the SLC6A4 gene contains a polymorphism with "short" and "long" repeats in a region: 5-HTT-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR or SERTPR).[8] The short variation has 14 repeats of a sequence while the long variation has 16 repeats.[6] The short variation leads to less transcription for SLC6A4, and it has been found that it can partly account for anxiety-related personality traits.[9] This polymorphism has been extensively investigated in over 300 scientific studies (as of 2006).[10] The 5-HTTLPR polymorphism may be subdivided further: One study published in 2000 found 14 allelic variants (14-A, 14-B, 14-C, 14-D, 15, 16-A, 16-B, 16-C, 16-D, 16-E, 16-F, 19, 20 and 22) in a group of around 200 Japanese and Caucasian people.[6]

The low-expression variant of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism (the short version) increased risk of socalled "posthurricane" post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression but only under the conditions of high hurricane exposure and low social support after adjustment for sex, ancestry, and age. Similar effects were found for major depression. High-risk individuals (high hurricane exposure, the low-expression 5-HTTLPR variant, low social support) were at 4.5 times the risk of developing PTSD and major depression of low-risk individuals.[11]

In addition to altering the expression of SERT protein and concentrations of extracellular serotonin in the brain, the 5-HTTLPR variation is associated with changes in brain structure. One study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[12] In another study, people who inherited two short alleles were found to have more neurons and a larger volume in the pulvinar and limbic regions of the thalamus. Enlargement of the thalamus and reduced cortical volume provides an anatomical basis for why people who inherit the 5-HTTLPRshort/short genotype are more vulnerable to major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide.[13] In contrast, a 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and autism.[14]

rs25532

rs25532 is a SNP (C>T) close to the site of 5-HTTLPR. It has been examined in connection with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).[15]

I425V

I425V is a rare mutation on the ninth exon. Researchers have found this genetic variation in unrelated families with OCD, and that it leads to faulty transporter function and regulation. A second variant in the same gene of some patients with this mutation suggests a genetic "double hit", resulting in greater biochemical effects and more severe symptoms.[16][17]

VNTR in STin2

Another noncoding polymorphism is a VNTR in the second intron (STin2). It is found with three alleles: 9, 10 and 12 repeats. A meta-analysis has found that the 12 repeat allele of the STin2 VNTR polymorphism had some minor (with odds ratio 1.24) but statistical significant association with schizophrenia.[18] A 2008 meta-analysis found no significant overall association between the STin2 VNTR polymorphism and autism.[14]

Neuroimaging

The distribution of the serotonin transporter in the brain may be imaged with positron emission tomography using radioligands called DASB and DAPP, and the first studies on the human brain were reported in 2000.[19] DASB and DAPP are not the only radioligands for the serotonin transporter. There are numerous others, with the most popular probably being the β-CIT radioligand with a iodine-123 isotope that is used for brain scanning with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).[20] The radioligands have been used to examine whether variables such as age, gender or genotype are associated with differential serotonin transporter binding.[21] Healthy subjects that have a high score of neuroticism — a personality trait in the Revised NEO Personality Inventory — have been found to have more serotonin transporter binding in the thalamus.[22]

Methodological issues

When the neuroimages from a DASB experiment are analyzed the kinetic models suggested by Ichise and coworkers[23] are often employed to estimate the binding potential. A test-retest reproducibility experiment has been performed to evaluate this approach for DASB.[24]

Neuroimaging and genetics

Studies on the serotonin transporter have combined neuroimaging and genetics methods, e.g., a voxel-based morphometry study found less grey matter in perigenual anterior cingulate cortex and amygdala for short allele carriers of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism compared to subjects with the long/long genotype.[25]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000108576 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000020838 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Donatella Marazziti, H.S. Akiskal, A. Rossi, G.B. Cassano (1999). "Alteration of the platelet serotonin transporter in romantic love". Psychological Medicine. 29 (3): 741–745. PMID 10405096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c M. Nakamura, S. Ueno, A. Sano & H. Tanabe (2000). "The human serotonin transporter gene linked polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) shows ten novel allelic variants". Molecular Psychiatry. 5: 32–38.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Dennis L. Murphy & Klaus-Peter Lesch (2008). "Targeting the murine serotonin transporter: insights into human neurobiology". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9: 85–96. doi:10.1038/nrn2284.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Armin Heils, Andreas Teufel, Susanne Petri, Gerald Stöber, Peter Riederer, Dietmar Bengel, & K. Peter Lesch (1996). "Allelic variation of human serotonin transporter gene expression". Journal of Neurochemistry. 66 (6): 2621–2624. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66062621.x. PMID 8632190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klaus-Peter Lesch, Dietmar Bengel, Armin Heils, Sue Z. Sabol, Benjamin D. Greenberg, Susanne Petri, Jonathan Benjamin, Clemens R. Müller, Dean H. Hamer, Dennis L. Murphy (1996). "Association of Anxiety-Related Traits with a Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene Regulatory Region". Science. 274 (5292). doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1527.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J.R. Wendland, B.J. Martin, M.R. Kruse, K.-P. Lesch, D.L. Murphy (2006). "Simultaneous genotyping of four functional loci of human SLCA4, with a reappraisal of 5-HTTLPR and rs255531". Molecular Psychiatry: 1–3. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001789.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dean G. Kilpatrick, Koenen KC, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Galea S, Resnick HS, Roitzsch J, Boyle J, Joel Gelernter (2007). "The serotonin transporter genotype and social support and moderation of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression in hurricane-exposed adults". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (11): 1693–1699. PMID 17974934.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Lukas Pezawas, Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, Emily M. Drabant, Beth A. Verchinski, Karen E. Munoz, Bhaskar S. Kolachana, Michael F. Egan, Venkata S. Mattay, Ahmaad R. Hariri & Daniel R. Weinberger (2005). "5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (6). doi:10.1038/nn1463.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Young KA, Holcomb LA, Yazdani U, Bonkale W, Hicks PB and German DC. 5HTTLPR polymorphism and enlargement of the pulvinar: Unlocking the backdoor to the limbic system. Biol Psychiatry. 2007. 61: 813-8 PMID 17083920.

- ^ a b Huang CH, Santangelo SL (2008). "Autism and serotonin transporter gene polymorphisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. doi:10.1002/ajmg.b.30720. PMID 18286633.

- ^ Wendland JR, Moya PR, Kruse MR, Ren-Patterson RF, Jensen CL, Cromer KR, Murphy DL (2007-11-30 (electronic)). "A novel, putative gain-of-function haplotype at SLC6A4 associates with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Hum Mol Genet. PMID 18055562.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ N. Ozaki, D. Goldman, W. H. Kaye, K. Plotnicov, B. D. Greenberg, J. Lappalainen, G. Rudnick and D. L. Murphy (2003). "Serotonin transporter missense mutation associated with a complex neuropsychiatric phenotype". Molecular Psychiatry. 8: 933–936. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001365.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) News article:- Reuters (2003-10-27). "Gene Found for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Mental Health E-News. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help)

- Reuters (2003-10-27). "Gene Found for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Mental Health E-News. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^

R Delorme, C Betancur, M Wagner, M O Krebs, P Gorwood, P Pearl, G Nygren, C M Durand, F Buhtz, P Pickering, J Melke, S Ruhrmann, H Anckarsäter, N Chabane, A Kipman, C Reck4, B Millet, I Roy, M C Mouren-Simeoni, W Maier, M Råstam, C Gillberg, M Leboyer and T Bourgeron (2005). "Support for the association between the rare functional variant I425V of the serotonin transporter gene and susceptibility to obsessive compulsive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 10: 1059–1061. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001728.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ J. B. Fan & P. Sklar (2005). "Meta-analysis reveals association between serotonin transporter gene STin2 VNTR polymorphism and schizophrenia". Molecular Psychiatry. 10 (10): 928–938. PMID 15940296.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ S. Houle, N. Ginovart, D. Hussey, J.H. Meyer, A.A. Wilson (2000). "Imaging the serotonin transporter with positron emission tomography: initial human studies with [11C]DAPP and [11C]DASB". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 27 (11). doi:10.1007/s002590000365.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ T. Brücke, J. Kornhuber, P. Angelberger, S. Asenbaum, H. Frassine, I. Podreka (1993). "SPECT imaging of dopamine and serotonin transporters with [123I]β-CIT. Binding kinetics in the human brain". Journal of Neural Transmission. 94 (2): 137–146. doi:10.1007/BF01245007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Peter Brust, Swen Hess and Ulrich Müller and Zsolt Szabo (2006). "Neuroimaging of the Serotonin Transporter — Possibilities and Pitfalls" (PDF). Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2 (1): 111–149.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Akihiro Takano, Ryosuke Arakawaa, Mika Hayashia, Hidehiko Takahashia, Hiroshi Itoa & Tetsuya Suhara (2007). "Relationship between neuroticism personality trait and serotonin transporter binding". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (6): 588–592. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.007. PMID 17336939.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Masanori Ichise, Jeih-San Liow, Jian-Qiang Lu, Akihiro Takano, Kendra Model, Hiroshi Toyama, Tetsuya Suhara, Kazutoshi Suzuki, Robert B Innis and Richard E Carson (2003). "Linearized Reference Tissue Parametric Imaging Methods: Application to [11C]DASB Positron Emission Tomography Studies of the Serotonin Transporter in Human Brain". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 23: 1096–1112. doi:10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jae Seung Kim, Masanori Ichise, Janet Sangare, and Robert B. Innis (2006). "PET Imaging of Serotonin Transporters with [11C]DASB: Test–Retest Reproducibility Using a Multilinear Reference Tissue Parametric Imaging Method". Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 47 (2): 208–214.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lukas Pezawas, Andreas Meyer-Lindenberg, Emily M. Drabant, Beth A. Verchinski, Karen E. Munoz, Bhaskar S. Kolachana, Michael F. Egan, Venkata S. Mattay, Ahmaad R. Hariri & Daniel R. Weinberger (2005). "5-HTTLPR polymorphism impacts human cingulate-amygdala interactions: a genetic susceptibility mechanism for depression". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (6). doi:10.1038/nn1463.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: year (link)

Further reading

- NIH press release: Serotonin Transporter Gene Shown to Influence College Drinking Habits

- J.P. Roiser, L.J. Cook, J.D. Cooper, D.C. Rubinsztein, B.J. Sahakian (2005). "Association of a Functional Polymorphism in the Serotonin Transporter Gene With Abnormal Emotional Processing in Ecstasy Users". American Journal of Psychiatry. 162 (3): 609–612.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)