Legal code (municipal): Difference between revisions

m moved Legal code to Legal code (municipal): this article only covers US and Canadian municipal code, not legal codes in general. |

replace as main article |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

*[http://www.portlandonline.com/BDS/index.cfm?c=debhj City of Portland, Oregon Code Violation Treatise] |

*[http://www.portlandonline.com/BDS/index.cfm?c=debhj City of Portland, Oregon Code Violation Treatise] |

||

[[Category:Legal codes |

[[Category:Legal codes]] |

||

[[de:Gesetzbuch]] |

[[de:Gesetzbuch]] |

||

Revision as of 22:57, 4 March 2008

A legal code is a body of law written by a governmental body, such as a U.S. state, a Canadian Province or German Bundesland or a municipality. Whether authored or merely adopted by a municipality, it is typically, though not exclusively, enforced by the municipality, as the Authority Having Jurisdiction.

Types of locally enforceable codes

include but are not limited to:

- Building code - enforced by building inspectors from the municipal building department

- Fire code - enforced by the local fire prevention officers from the local fire department

- Noise Control Code - enforced by municipal bylaw officers

Guideline codes

Some national and regional governments may issue model codes, such as a model building code. Examples include the National Building Code of Canada, the National Fire Code of Canada and Germany's MBO - Musterbauordnung. All three aforementioned examples are issued as guideline documents, which are then used by their Provinces and Bundesländer, respectively, as a baseline to author their own building codes, such as the Ontario Building Code (OBC) and fire codes, such as the Alberta Fire Code (AFC), respectively, which must then, in turn, also be adopted by the municipalities, before they become local law, which is then locally enforced by the municipalities. Usually, the municipality passes a by-law to adopt the code, so the same book applies across that whole territory or Province, etc.. Alternatively, a municipality may elect to issue its own version, such as The City of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, which typically makes its own changes to the British Columbia Building Code (BCBC), and then issues its own Vancouver Building By-law, rather than to simply adopt the BCBC, as all other municipalities in British Columbia do.

Code writing process

Typically, volunteers gather in committees at the location of the issuing authority to write and edit the code. Volunteers in both codes and standards writing are generally considered to be stakeholders. The governing body is generally intended to ensure that no one type of stakeholder dominates in order to be able to produce a more balanced and legally defencible final document. General principles of law and philosophy prevailing in the region may also have an influence.

Influencing factors upon code writing process

Example legal codes that rely heavily on precedent and the opinions of prior jurists include English common law and U.S. Constitutional Law. By contrast most implementations of Islamic Shariah. Napoleonic Code, Chinese Law and German Law, emphasize very specific philosophical principles rooted in Islam, French, Chinese, and German philosophy respectively - the role of precedent and prior jurists is much reduced and that of current judges enhanced - thus these can be seen as an ethical code which applies to the jurists themselves. In construction, precedents may include experience gained through fire losses and structural collapse. Lessons learned can be incorporated into revised codes or updates to prevent further losses.

If a legal system is not controlled by a single institution, the legal code typically includes ways to balance the power of different participants (sometimes known as checks and balances). These measures can reduce the potential for one group of participants to develop a monopoly over the legal system. For example, in a representative democracy, it may be required that elected officials make or vote on any changes to the law.

Apart from the foregoing, industry organisations tend to engage in attempts to influence the code writing process through participating in meetings of task committees and groups and providing evidence to make their cases. An example is the fire sprinkler lobby, which favours active fire protection, whereas members of the passive fire protection trades, for instance the International Firestop Council would argue the merits of its members' work. Stakeholders also include insurance companies, who stand to gain by keeping the operating risks of buildings low, whereas a real-estate developer may seek to keep costs low.

Purpose of a legal code

Generally, a legal code serves the dual purpose of broadcasting a certain idea of public morality as well as technical fact, and disclosing the retribution that the society, via the enforcing body, will visit on those who offend that morality. As an example, penalties are imposed for constructing an unsafe building or engaging in actions that will negatively impact the safety of a building. The severity of the punishment is intended to be commensurate with the severity of the offence.

Code violations

Since there are different types of codes, with differing levels of public safety impact, the severity of consequences and punishment varies. Violating the noise control code inside an apartment may just annoy the neighbours. Building and fire code violations, however, can affect anyone inside and even surrounding a building.

Perpetrators include, but are not limited to the following:

- General contractor (through use of inadmissible shortcuts)

- Subcontractor (through use of inadmissible shortcuts)

- Architect (through errors in plans (drawings) and specifications

- Building owner (through alterations of building components or the occupancy without a building permit).

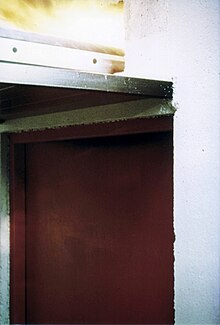

- Occupants (sabotage or ignorance, for example, propping open a fire door and running a carpet through it.)

- Authority Having Jurisdiction (through approval of a condition that violates the local code.)

- Developers (through insisting on lowering costs by reducing safety measures, for instance accepting unspecified alternative products and systems)

Arguing disputes

For predictability, a legal code usually includes a body of prior decisions or precedent, which with the law itself constitutes what is called a jurisprudence. A jurist is an individual who makes judgements that are incorporated into the jurisprudence, either as cases or as laws themselves.

To speed cases along and ensure uniform representation, many legal codes require a defendant or plaintiff to be represented by an attorney at law, whose responsibility is to take the client's case without prejudice, and to their best to minimize the penalties applied by law, including ideally the release of their client from any responsibility at all.

Computer code

Recently Lawrence Lessig has argued in his book Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace that computer code may regulate conduct in much the same way that legal codes do.

See also

- Attorney at law

- Civil code

- Ethical code

- Jurist

- Moral code

- Building code

- Fire code

- Authority Having Jurisdiction