Big Bang: Difference between revisions

Art LaPella (talk | contribs) m capitalization |

|||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

{{see also|Timeline of cosmology|History of astronomy}} |

{{see also|Timeline of cosmology|History of astronomy}} |

||

The Big Bang theory developed from observations of the structure of the universe and from theoretical considerations. In 1912 [[Vesto Slipher]] measured the first [[Doppler shift]] of a "[[spiral nebula]]" (spiral nebula is the obsolete term for spiral galaxies), and soon discovered that almost all such nebulae were receding from Earth. He did not grasp the cosmological implications of this fact, and indeed at the time it was [[Shapley-Curtis debate|highly controversial]] whether or not these nebulae were "island universes" outside our [[Milky Way]].<ref>{{cite journal | first = V. M. | last = Slipher | authorlink=Vesto Slipher | title=The radial velocity of the Andromeda nebula | journal = Lowell Observatory Bulletin | volume=1 | pages=56–57 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1913LowOB...2...56S}}<br /> |

The Big Bang theory developed from observations of the structure of the universe and from theoretical considerations. In 1912 [[Vesto Slipher]] measured the first [[Doppler shift]] of a "[[spiral nebula]]" (spiral nebula is the obsolete term for spiral galaxies), and soon discovered that almost all such nebulae were receding from Earth. He did not grasp the cosmological implications of this fact, and indeed at the time it was [[Shapley-Curtis debate|highly controversial]] whether or not these nebulae were "island universes" outside our [[Milky Way]].<ref>{{cite journal | first = V. M. | last = Slipher | authorlink=Vesto Slipher | title=The radial velocity of the Andromeda nebula | journal = Lowell Observatory Bulletin | volume=1 | pages=56–57 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1913LowOB...2...56S}}<br /> |

||

{{cite journal | first = V. M. | last = Slipher | authorlink=Vesto Slipher | title = Spectrographic observations of nebulae | journal = Popular Astronomy | volume=23 | pages=21–24 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1915PA.....23Q..21S}}</ref> Ten years later, [[Alexander Alexandrovich Friedman|Alexander Friedmann]], a [[Russia]]n [[physical cosmology|cosmologist]] and [[mathematician]], derived the [[Friedmann equations]] from [[Albert Einstein]]'s [[Einstein equation|equations]] of [[general relativity]], showing that the universe might be expanding in contrast to the [[static universe]] model advocated by Einstein.<ref name=af1922>{{cite journal | last=Friedman | first=A | authorlink=Alexander Alexandrovich Friedman | title= Über die Krümmung des Raumes | journal=Z. Phys. | volume=10 | year=1922 | pages=377–386}} {{de icon}} (English translation in: {{cite journal | first=A | last=Friedman | title=On the Curvature of Space | journal=General Relativity and Gravitation | volume=31 | year=1999 | pages= 1991–2000 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999GReGr..31.1991F | doi=10.1023/A:1026751225741}})</ref> In 1924, [[Edwin Hubble]]'s measurement of the great distance to the nearest spiral nebulae showed that these systems were indeed other [[galaxies]]. Independently deriving Friedmann's equations in 1927, [[Georges Lemaître]], a Belgian Roman Catholic priest, predicted that the recession of the nebulae was due to the expansion of the universe.<ref name=gl1927>{{cite journal | first=G. | last=Lemaître | title=Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques | journal=Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels | volume=47A |date=1927 | pages=41}} {{fr icon}} Translated in: {{cite journal | journal=[[Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society]] | volume=91 |date=1931 | pages=483–490 | title=Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..483L}}</ref> In 1931 Lemaître went further and suggested that the universe |

{{cite journal | first = V. M. | last = Slipher | authorlink=Vesto Slipher | title = Spectrographic observations of nebulae | journal = Popular Astronomy | volume=23 | pages=21–24 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1915PA.....23Q..21S}}</ref> Ten years later, [[Alexander Alexandrovich Friedman|Alexander Friedmann]], a [[Russia]]n [[physical cosmology|cosmologist]] and [[mathematician]], derived the [[Friedmann equations]] from [[Albert Einstein]]'s [[Einstein equation|equations]] of [[general relativity]], showing that the universe might be expanding in contrast to the [[static universe]] model advocated by Einstein.<ref name=af1922>{{cite journal | last=Friedman | first=A | authorlink=Alexander Alexandrovich Friedman | title= Über die Krümmung des Raumes | journal=Z. Phys. | volume=10 | year=1922 | pages=377–386}} {{de icon}} (English translation in: {{cite journal | first=A | last=Friedman | title=On the Curvature of Space | journal=General Relativity and Gravitation | volume=31 | year=1999 | pages= 1991–2000 | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999GReGr..31.1991F | doi=10.1023/A:1026751225741}})</ref> In 1924, [[Edwin Hubble]]'s measurement of the great distance to the nearest spiral nebulae showed that these systems were indeed other [[galaxies]]. Independently deriving Friedmann's equations in 1927, [[Georges Lemaître]], a Belgian physicist and Roman Catholic priest, predicted that the recession of the nebulae was due to the expansion of the universe.<ref name=gl1927>{{cite journal | first=G. | last=Lemaître | title=Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques | journal=Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels | volume=47A |date=1927 | pages=41}} {{fr icon}} Translated in: {{cite journal | journal=[[Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society]] | volume=91 |date=1931 | pages=483–490 | title=Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae | url=http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1931MNRAS..91..483L}}</ref> |

||

In 1931 Lemaître went further and suggested that the evident expansion in forward time required that the universe contracted backwards in time, and would continue to do so until it could contract no further, bringing all the mass of the universe into a single point, a "primeval [[atom]]", at a point in time before which time and space did not exist. As such, at this point, the fabric of time and space had not yet come into existence. This perhaps echoed previous speculations about the [[cosmic egg]] origin of the universe.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lemaître, G. | title= The evolution of the universe: discussion | journal = [[Nature]] | volume = 128 | year = 1931 | pages = suppl.: 704}}</ref> |

|||

Starting in 1924, Hubble painstakingly developed a series of distance indicators, the forerunner of the [[cosmic distance ladder]], using the {{convert|100|in|mm|sing=on}} Hooker telescope at [[Mount Wilson Observatory]]. This allowed him to estimate distances to galaxies whose [[redshift]]s had already been measured, mostly by Slipher. In 1929, Hubble discovered a correlation between distance and recession velocity—now known as [[Hubble's law]].<ref name="hubble">{{cite journal|title=A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae|author=Edwin Hubble|journal=[[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]]|volume=15|pages=168–173|date=1929|url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/15/3/168}}</ref><ref name="christianson">{{cite book|author=E. Christianson|title=Edwin Hubble: Mariner of the Nebulae | year=1995 | publisher=Farrar Straus & Giroux | id=ISBN 0374146608}}</ref> Lemaître had already shown that this was expected, given the [[cosmological principle]].<ref name="peebles">{{cite journal|author=P. J. E. Peebles and Bharat Ratra|title=The cosmological constant and dark energy|date=2003|journal=Reviews of Modern Physics|volume=75|pages=559–606 | doi=10.1103/RevModPhys.75.559 | id={{arxiv|archive=astro-ph|id=0207347}}}}</ref> |

Starting in 1924, Hubble painstakingly developed a series of distance indicators, the forerunner of the [[cosmic distance ladder]], using the {{convert|100|in|mm|sing=on}} Hooker telescope at [[Mount Wilson Observatory]]. This allowed him to estimate distances to galaxies whose [[redshift]]s had already been measured, mostly by Slipher. In 1929, Hubble discovered a correlation between distance and recession velocity—now known as [[Hubble's law]].<ref name="hubble">{{cite journal|title=A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae|author=Edwin Hubble|journal=[[Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]]|volume=15|pages=168–173|date=1929|url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/15/3/168}}</ref><ref name="christianson">{{cite book|author=E. Christianson|title=Edwin Hubble: Mariner of the Nebulae | year=1995 | publisher=Farrar Straus & Giroux | id=ISBN 0374146608}}</ref> Lemaître had already shown that this was expected, given the [[cosmological principle]].<ref name="peebles">{{cite journal|author=P. J. E. Peebles and Bharat Ratra|title=The cosmological constant and dark energy|date=2003|journal=Reviews of Modern Physics|volume=75|pages=559–606 | doi=10.1103/RevModPhys.75.559 | id={{arxiv|archive=astro-ph|id=0207347}}}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:13, 16 March 2008

The Big Bang is a cosmological model of the universe that has become well supported by several independent observations. After Edwin Hubble discovered that galactic distances were generally proportional to their redshifts in 1929, this observation was taken to indicate that the universe is expanding. If the universe is seen to be expanding today, then it must have been smaller, denser, and hotter in the past. This idea has been considered in detail all the way back to extreme densities and temperatures, and the resulting conclusions have been found to conform very closely to what is observed.

Ironically, the term 'Big Bang' was first coined by Fred Hoyle in a derisory statement seeking to belittle the credibility of the theory that he did not believe to be true.[1] However, the discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1964 was taken as almost undeniable support for the Big Bang.

Analysis of the spectrum of light from distant galaxies reveals a shift towards longer wavelengths proportional to each galaxy's distance in a relationship described by Hubble's law, which is taken to indicate that the universe is undergoing a continuous expansion. Furthermore, the cosmic microwave background radiation discovered in 1964 provides strong evidence that due to the expansion, the universe has naturally cooled from an extremely hot, dense initial state. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background led to almost universal acceptance among physicists, astronomers, and astrophysicists that the Big Bang describes the evolution of the universe quite well, at least in its broad outline.

Further evidence supporting the Big Bang model comes from the relative proportion of light elements in the universe. The observed abundances of hydrogen and helium throughout the cosmos closely match the calculated predictions for the formation of these elements from nuclear processes in the rapidly expanding and cooling first minutes of the universe, as logically and quantitatively detailed according to Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

However, there are mysteries of the universe that are not explained by the Big Bang model alone. For example, a region of the universe 12 billion lightyears distant in one direction appears little different than a region 12 billion lightyears distant in the opposite direction. But since the universe is 'only' around 13.7 billion years old, it would appear these regions could never have been causally connected. How, then, can they be so similar? Alan Guth's 1981 theory of cosmic inflation, a short, sudden burst of extreme exponential expansion in the very early universe, provided an explanation for this horizon problem and several of the features unaccounted for by the original Big Bang model. The successor to Guth's original theory has found some circumstantial support, but it is not yet nearly as well supported as the Big Bang model.

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

History

The Big Bang theory developed from observations of the structure of the universe and from theoretical considerations. In 1912 Vesto Slipher measured the first Doppler shift of a "spiral nebula" (spiral nebula is the obsolete term for spiral galaxies), and soon discovered that almost all such nebulae were receding from Earth. He did not grasp the cosmological implications of this fact, and indeed at the time it was highly controversial whether or not these nebulae were "island universes" outside our Milky Way.[2] Ten years later, Alexander Friedmann, a Russian cosmologist and mathematician, derived the Friedmann equations from Albert Einstein's equations of general relativity, showing that the universe might be expanding in contrast to the static universe model advocated by Einstein.[3] In 1924, Edwin Hubble's measurement of the great distance to the nearest spiral nebulae showed that these systems were indeed other galaxies. Independently deriving Friedmann's equations in 1927, Georges Lemaître, a Belgian physicist and Roman Catholic priest, predicted that the recession of the nebulae was due to the expansion of the universe.[4]

In 1931 Lemaître went further and suggested that the evident expansion in forward time required that the universe contracted backwards in time, and would continue to do so until it could contract no further, bringing all the mass of the universe into a single point, a "primeval atom", at a point in time before which time and space did not exist. As such, at this point, the fabric of time and space had not yet come into existence. This perhaps echoed previous speculations about the cosmic egg origin of the universe.[5]

Starting in 1924, Hubble painstakingly developed a series of distance indicators, the forerunner of the cosmic distance ladder, using the 100-inch (2,500 mm) Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory. This allowed him to estimate distances to galaxies whose redshifts had already been measured, mostly by Slipher. In 1929, Hubble discovered a correlation between distance and recession velocity—now known as Hubble's law.[6][7] Lemaître had already shown that this was expected, given the cosmological principle.[8]

During the 1930s other ideas were proposed as non-standard cosmologies to explain Hubble's observations, including the Milne model,[9] the oscillatory universe (originally suggested by Friedmann, but advocated by Einstein and Richard Tolman)[10] and Fritz Zwicky's tired light hypothesis.[11]

After World War II, two distinct possibilities emerged. One was Fred Hoyle's steady state model, whereby new matter would be created as the universe seemed to expand. In this model, the universe is roughly the same at any point in time.[12] The other was Lemaître's Big Bang theory, advocated and developed by George Gamow, who introduced big bang nucleosynthesis[13] and whose associates, Ralph Alpher and Robert Herman, predicted the cosmic microwave background (CMB).[14] It is an irony that it was Hoyle who coined the name that would come to be applied to Lemaître's theory, referring to it as "this big bang idea" in derision during a 1950 BBC radio broadcast.[15][16] For a while, support was split between these two theories. Eventually, the observational evidence, most notably from radio source counts, began to favor the latter. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation in 1964[17] secured the Big Bang as the best theory of the origin and evolution of the cosmos. Much of the current work in cosmology includes understanding how galaxies form in the context of the Big Bang, understanding the physics of the universe at earlier and earlier times, and reconciling observations with the basic theory.

Huge strides in Big Bang cosmology have been made since the late 1990s as a result of major advances in telescope technology as well as the analysis of copious data from satellites such as COBE,[18] the Hubble Space Telescope and WMAP.[19] Cosmologists now have fairly precise measurement of many of the parameters of the Big Bang model, and have made the unexpected discovery that the expansion of the universe appears to be accelerating.

Overview

Timeline of the Big Bang

Extrapolation of the expansion of the universe backwards in time using general relativity yields an infinite density and temperature at a finite time in the past.[20] This singularity signals the breakdown of general relativity. How closely we can extrapolate towards the singularity is debated—certainly not earlier than the Planck epoch. The early hot, dense phase is itself referred to as "the Big Bang",[21] and is considered the "birth" of our universe. Based on measurements of the expansion using Type Ia supernovae, measurements of temperature fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background, and measurements of the correlation function of galaxies, the universe has a calculated age of 13.7 ± 0.2 billion years.[22] The agreement of these three independent measurements strongly supports the ΛCDM model that describes in detail the contents of the universe.

The earliest phases of the Big Bang are subject to much speculation. In the most common models, the universe was filled homogeneously and isotropically with an incredibly high energy density, huge temperatures and pressures, and was very rapidly expanding and cooling. Approximately 10−35 seconds into the expansion, a phase transition caused a cosmic inflation, during which the universe grew exponentially.[23] After inflation stopped, the universe consisted of a quark-gluon plasma, as well as all other elementary particles.[24] Temperatures were so high that the random motions of particles were at relativistic speeds, and particle-antiparticle pairs of all kinds were being continuously created and destroyed in collisions. At some point an unknown reaction called baryogenesis violated the conservation of baryon number, leading to a very small excess of quarks and leptons over antiquarks and anti-leptons—of the order of 1 part in 30 million. This resulted in the predominance of matter over antimatter in the present universe.[25]

The universe continued to grow in size and fall in temperature, hence the typical energy of each particle was decreasing. Symmetry breaking phase transitions put the fundamental forces of physics and the parameters of elementary particles into their present form.[26] After about 10−11 seconds, the picture becomes less speculative, since particle energies drop to values that can be attained in particle physics experiments. At about 10−6 seconds, quarks and gluons combined to form baryons such as protons and neutrons. The small excess of quarks over antiquarks led to a small excess of baryons over antibaryons. The temperature was now no longer high enough to create new proton-antiproton pairs (similarly for neutrons-antineutrons), so a mass annihilation immediately followed, leaving just one in 1010 of the original protons and neutrons, and none of their antiparticles. A similar process happened at about 1 second for electrons and positrons. After these annihilations, the remaining protons, neutrons and electrons were no longer moving relativistically and the energy density of the universe was dominated by photons (with a minor contribution from neutrinos).

A few minutes into the expansion, when the temperature was about a billion (one thousand million; 109; SI prefix giga) Kelvin and the density was about that of air, neutrons combined with protons to form the universe's deuterium and helium nuclei in a process called Big Bang nucleosynthesis.[27] Most protons remained uncombined as hydrogen nuclei. As the universe cooled, the rest mass energy density of matter came to gravitationally dominate that of the photon radiation. After about 380,000 years the electrons and nuclei combined into atoms (mostly hydrogen); hence the radiation decoupled from matter and continued through space largely unimpeded. This relic radiation is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation.[28]

Over a long period of time, the slightly denser regions of the nearly uniformly distributed matter gravitationally attracted nearby matter and thus grew even denser, forming gas clouds, stars, galaxies, and the other astronomical structures observable today. The details of this process depend on the amount and type of matter in the universe. The three possible types of matter are known as cold dark matter, hot dark matter and baryonic matter. The best measurements available (from WMAP) show that the dominant form of matter in the universe is cold dark matter. The other two types of matter make up less than 20% of the matter in the universe.[19]

The universe today appears to be dominated by a mysterious form of energy known as dark energy. Approximately 70% of the total energy density of today's universe is in this form. This dark energy causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate, observed as a slower than expected expansion at very large distances. Dark energy in its simplest formulation takes the form of a cosmological constant term in Einstein's field equations of general relativity, but its composition is unknown and, more generally, the details of its equation of state and relationship with the standard model of particle physics continue to be investigated both observationally and theoretically.[8]

All these observations can be explained by the ΛCDM model of cosmology, which is a mathematical model of the Big Bang with six free parameters, describing the universe after the inflationary epoch. As noted above, there is no compelling physical model for the first 10−11 seconds of the universe. To resolve the paradox of the initial singularity, a theory of quantum gravitation is needed. Understanding this period of the history of the universe is one of the greatest unsolved problems in physics.

Big bang theory assumptions

The Big Bang theory depends on two major assumptions: the universality of physical laws, and the cosmological principle. The cosmological principle states that on large scales the universe is homogeneous and isotropic.

These ideas were initially taken as postulates, but today there are efforts to test each of them. For example, the first assumption has been tested by observations showing that largest possible deviation of the fine structure constant over much of the age of the universe is of order 10−5.[29] Also, General Relativity has passed stringent tests on the scale of the solar system and binary stars while extrapolation to cosmological scales has been validated by the empirical successes of various aspects of the Big Bang theory.[30]

If the large-scale universe appears isotropic as viewed from Earth, the cosmological principle can be derived from the simpler Copernican principle, which states that there is no preferred (or special) observer or vantage point. To this end, the cosmological principle has been confirmed to a level of 10−5 via observations of the CMB.[31] The universe has been measured to be homogeneous on the largest scales at the 10% level.[32]

FLRW metric

General relativity describes spacetime by a metric, which determines the distances that separate nearby points. The points, which can be galaxies, stars, or other objects, themselves are specified using a coordinate chart or "grid" that is laid down over all spacetime. The cosmological principle implies that the metric should be homogeneous and isotropic on large scales, which uniquely singles out the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric (FLRW metric). This metric contains a scale factor, which describes how the size of the universe changes with time. This enables a convenient choice of a coordinate system to be made, called comoving coordinates. In this coordinate system, the grid expands along with the universe, and objects that are moving only due to the expansion of the universe remain at fixed points on the grid. While their coordinate distance (comoving distance) remains constant, the physical distance between two such comoving points expands proportionally with the scale factor of the universe.[33]

The Big Bang is not an explosion of matter moving outward to fill an empty universe. Instead, space itself expands with time everywhere and increases the physical distance between two comoving points. Because the FLRW metric assumes a uniform distribution of mass and energy, it applies to our universe only on large scales—local concentrations of matter such as our galaxy are gravitationally bound and as such do not experience the large-scale expansion of space.

Horizons

An important feature of the Big Bang spacetime is the presence of horizons. Since the universe has a finite age, and light travels at a finite speed, there may be events in the past whose light has not had time to reach us. This places a limit or a past horizon on the most distant objects that can be observed. Conversely, because space is expanding, and more distant objects are receding ever more quickly, light emitted by us today may never "catch up" to very distant objects. This defines a future horizon, which limits the events in the future that we will be able to influence. The presence of either type of horizon depends on the details of the FRW model that describes our universe. Our understanding of the universe back to very early times suggests that there was a past horizon, though in practice our view is limited by the opacity of the universe at early times. If the expansion of the universe continues to accelerate, there is a future horizon as well.[34]

Observational evidence

The earliest and most direct kinds of observational evidence are the Hubble-type expansion seen in the redshifts of galaxies, the detailed measurements of the cosmic microwave background, and the abundance of light elements (see Big Bang nucleosynthesis). These are sometimes called the three pillars of the big bang theory. Many other lines of evidence now support the picture, notably various properties of the large-scale structure of the cosmos[35] which are predicted to occur due to gravitational growth of structure in the standard Big Bang theory.

Hubble's law and the expansion of space

Observations of distant galaxies and quasars show that these objects are redshifted—the light emitted from them has been shifted to longer wavelengths. This can be seen by taking a frequency spectrum of an object and matching the spectroscopic pattern of emission lines or absorption lines corresponding to atoms of the chemical elements interacting with the light. These redshifts are uniformly isotropic, distributed evenly among the observed objects in all directions. If the redshift is interpreted as a Doppler shift, the recessional velocity of the object can be calculated. For some galaxies, it is possible to estimate distances via the cosmic distance ladder. When the recessional velocities are plotted against these distances, a linear relationship known as Hubble's law is observed:[6]

where

- is the recessional velocity of the galaxy or other distant object

- is the distance to the object and

- is Hubble's constant, measured to be (70 +2.4/-3.2) (km/s)/Mpc by the WMAP probe.[22]

Hubble's law has two possible explanations. Either we are at the center of an explosion of galaxies—which is untenable given the Copernican principle—or the universe is uniformly expanding everywhere. This universal expansion was predicted from general relativity by Alexander Friedman in 1922[3] and Georges Lemaître in 1927,[4] well before Hubble made his 1929 analysis and observations, and it remains the cornerstone of the Big Bang theory as developed by Friedmann, Lemaître, Robertson and Walker.

The theory requires the relation to hold at all times, where is the proper distance, , and , , and all vary as the universe expands (hence we write to denote the present-day Hubble "constant"). For distances much smaller than the size of the observable universe, the Hubble redshift can be thought of as the Doppler shift corresponding to the recession velocity . However, the redshift is not a true Doppler shift, but rather the result of the expansion of the universe between the time the light was emitted and the time that it was detected.[36]

That space is undergoing metric expansion is shown by direct observational evidence of the Cosmological Principle and the Copernican Principle, which together with Hubble's law have no other explanation. Astronomical redshifts are extremely isotropic and homogenous,[6] supporting the Cosmological Principle that the universe looks the same in all directions, along with much other evidence. If the redshifts were the result of an explosion from a center distant from us, they would not be so similar in different directions.

Measurements of the effects of the cosmic microwave background radiation on the dynamics of distant astrophysical systems in 2000 proved the Copernican principle, that the Earth is not in a central position, on a cosmological scale.[37] Radiation from the Big Bang was demonstrably warmer at earlier times throughout the universe. Uniform cooling of the cosmic microwave background over billions of years is explainable only if the universe is experiencing a metric expansion, and excludes the possibility that we are near the unique center of an explosion.

Cosmic microwave background radiation

During the first few days of the universe, the universe was in full thermal equilibrium, with photons being continually emitted and absorbed, giving the radiation a blackbody spectrum. As the universe expanded, it cooled to a temperature at which photons could no longer be created or destroyed. The temperature was still high enough for electrons and nuclei to remain unbound, however, and photons were constantly "reflected" from these free electrons through a process called Thomson scattering. Because of this repeated scattering, the early universe was opaque to light.

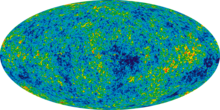

When the temperature fell to a few thousand Kelvin, electrons and nuclei began to combine to form atoms, a process known as recombination. Since photons scatter infrequently from neutral atoms, radiation decoupled from matter when nearly all the electrons had recombined, at the epoch of last scattering, 380,000 years after the Big Bang. These photons make up the CMB that is observed today, and the observed pattern of fluctuations in the CMB is a direct picture of the universe at this early epoch. The energy of photons was subsequently redshifted by the expansion of the universe, which preserved the blackbody spectrum but caused its temperature to fall, meaning that the photons now fall into the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum. The radiation is thought to be observable at every point in the universe, and comes from all directions with (almost) the same intensity.

In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson accidentally discovered the cosmic background radiation while conducting diagnostic observations using a new microwave receiver owned by Bell Laboratories.[17] Their discovery provided substantial confirmation of the general CMB predictions—the radiation was found to be isotropic and consistent with a blackbody spectrum of about 3 K—and it pitched the balance of opinion in favor of the Big Bang hypothesis. Penzias and Wilson were awarded a Nobel Prize for their discovery.

In 1989, NASA launched the Cosmic Background Explorer satellite (COBE), and the initial findings, released in 1990, were consistent with the Big Bang's predictions regarding the CMB. COBE found a residual temperature of 2.726 K and in 1992 detected for the first time the fluctuations (anisotropies) in the CMB, at a level of about one part in 105.[18] John C. Mather and George Smoot were awarded Nobels for their leadership in this work. During the following decade, CMB anisotropies were further investigated by a large number of ground-based and balloon experiments. In 2000–2001, several experiments, most notably BOOMERanG, found the universe to be almost geometrically flat by measuring the typical angular size (the size on the sky) of the anisotropies. (See shape of the universe.)

In early 2003, the first results of the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy satellite (WMAP) were released, yielding what were at the time the most accurate values for some of the cosmological parameters. This satellite also disproved several specific cosmic inflation models, but the results were consistent with the inflation theory in general.[22] This satellite is still gathering data. Another satellite will be launched within the next few years, the Planck Surveyor, which will provide even more accurate measurements of the CMB anisotropies. Many other ground- and balloon-based experiments are also currently running; see Cosmic microwave background experiments.

The background radiation is exceptionally smooth, which presented a problem in that conventional expansion would mean that photons coming from opposite directions in the sky were coming from regions that had never been in contact with each other. The leading explanation for this far reaching equilibrium is that the universe had a brief period of rapid exponential expansion, called inflation. This would have the effect of driving apart regions that had been in equilibrium, so that all the observable universe was from the same equilibrated region.

Abundance of primordial elements

Using the Big Bang model it is possible to calculate the concentration of helium-4, helium-3, deuterium and lithium-7 in the universe as ratios to the amount of ordinary hydrogen, H.[27] All the abundances depend on a single parameter, the ratio of photons to baryons, which itself can be calculated independently from the detailed structure of CMB fluctuations. The ratios predicted (by mass, not by number) are about 0.25 for 4He/H, about 10−3 for ²H/H, about 10−4 for ³He/H and about 10−9 for 7Li/H.[27]

The measured abundances all agree at least roughly with those predicted from a single value of the baryon-to-photon ratio. The agreement is excellent for deuterium, close but formally discrepant for 4He, and a factor of two off for 7Li; in the latter two cases there are substantial systematic uncertainties. Nonetheless, the general consistency with abundances predicted by BBN is strong evidence for the Big Bang, as the theory is the only known explanation for the relative abundances of light elements, and it is virtually impossible to "tune" the Big Bang to produce much more or less than 20–30% helium.[38] Indeed there is no obvious reason outside of the Big Bang that, for example, the young universe (i.e., before star formation, as determined by studying matter supposedly free of stellar nucleosynthesis products) should have more helium than deuterium or more deuterium than ³He, and in constant ratios, too.

Galactic evolution and distribution

Detailed observations of the morphology and distribution of galaxies and quasars provide strong evidence for the Big Bang. A combination of observations and theory suggest that the first quasars and galaxies formed about a billion years after the Big Bang, and since then larger structures have been forming, such as galaxy clusters and superclusters. Populations of stars have been aging and evolving, so that distant galaxies (which are observed as they were in the early universe) appear very different from nearby galaxies (observed in a more recent state). Moreover, galaxies that formed relatively recently appear markedly different from galaxies formed at similar distances but shortly after the Big Bang. These observations are strong arguments against the steady-state model. Observations of star formation, galaxy and quasar distributions and larger structures agree well with Big Bang simulations of the formation of structure in the universe and are helping to complete details of the theory.[39]

Other lines of evidence

After some controversy, the age of universe as estimated from the Hubble expansion and the CMB is now in good agreement with (i.e., slightly larger than) the ages of the oldest stars, both as measured by applying the theory of stellar evolution to globular clusters and through radiometric dating of individual Population II stars.

The prediction that the CMB temperature was higher in the past has been experimentally supported by observations of temperature-sensitive emission lines in gas clouds at high redshift. This prediction also implies that the amplitude of the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect in clusters of galaxies does not depend directly on redshift; this seems to be roughly true, but unfortunately the amplitude does depend on cluster properties which do change substantially over cosmic time, so a precise test is impossible.

Features, issues and problems

While very few researchers now doubt the Big Bang occurred, the scientific community was once divided between supporters of the Big Bang and those of alternative cosmological models. Throughout the historical development of the subject, problems with the Big Bang theory were posed in the context of a scientific controversy regarding which model could best describe the cosmological observations (see the history section above). With the overwhelming consensus in the community today supporting the Big Bang model, many of these problems are remembered as being mainly of historical interest; the solutions to them have been obtained either through modifications to the theory or as the result of better observations. Other issues, such as the cuspy halo problem and the dwarf galaxy problem of cold dark matter, are not considered to be fatal as it is anticipated that they can be solved through further refinements of the theory.

The core ideas of the Big Bang—the expansion, the early hot state, the formation of helium, the formation of galaxies—are derived from many independent observations including Big Bang nucleosynthesis, the cosmic microwave background, large scale structure and Type Ia supernovae, and can hardly be doubted as important and real features of our universe.

Precise modern models of the Big Bang appeal to various exotic physical phenomena that have not been observed in terrestrial laboratory experiments or incorporated into the Standard Model of particle physics. Of these features, dark energy and dark matter are considered the most secure, while inflation and baryogenesis remain speculative: they provide satisfying explanations for important features of the early universe, but could be replaced by alternative ideas without affecting the rest of the theory.[40] Explanations for such phenomena remain at the frontiers of inquiry in physics.

Horizon problem

The horizon problem results from the premise that information cannot travel faster than light. In a universe of finite age, this sets a limit—the particle horizon—on the separation of any two regions of space that are in causal contact.[41] The observed isotropy of the CMB is problematic in this regard: if the universe had been dominated by radiation or matter at all times up to the epoch of last scattering, the particle horizon at that time would correspond to about 2 degrees on the sky. There would then be no mechanism to cause these regions to have the same temperature.

A resolution to this apparent inconsistency is offered by inflationary theory in which a homogeneous and isotropic scalar energy field dominates the universe at some very early period (before baryogenesis). During inflation, the universe undergoes exponential expansion, and the particle horizon expands much more rapidly than previously assumed, so that regions presently on opposite sides of the observable universe are well inside each other's particle horizon. The observed isotropy of the CMB then follows from the fact that this larger region was in causal contact before the beginning of inflation.

Heisenberg's uncertainty principle predicts that during the inflationary phase there would be quantum thermal fluctuations, which would be magnified to cosmic scale. These fluctuations serve as the seeds of all current structure in the universe. Inflation predicts that the primordial fluctuations are nearly scale invariant and Gaussian, which has been accurately confirmed by measurements of the CMB.

Flatness/oldness problem

The flatness problem (also known as the oldness problem) is an observational problem associated with a Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric.[41] The universe may have positive, negative or zero spatial curvature depending on its total energy density. Curvature is negative if its density is less than the critical density, positive if greater, and zero at the critical density, in which case space is said to be flat. The problem is that any small departure from the critical density grows with time, and yet the universe today remains very close to flat.[42] Given that a natural timescale for departure from flatness might be the Planck time, 10−43 seconds, the fact that the universe has reached neither a Heat Death nor a Big Crunch after billions of years requires some explanation. For instance, even at the relatively late age of a few minutes (the time of nucleosynthesis), the universe must have been within one part in 1014 of the critical density, or it would not exist as it does today.[43]

A resolution to this problem is offered by inflationary theory. During the inflationary period, spacetime expanded to such an extent that its curvature would have been smoothed out. Thus, it is believed that inflation drove the universe to a very nearly spatially flat state, with almost exactly the critical density.

Magnetic monopoles

The magnetic monopole objection was raised in the late 1970s. Grand unification theories predicted topological defects in space that would manifest as magnetic monopoles. These objects would be produced efficiently in the hot early universe, resulting in a density much higher than is consistent with observations, given that searches have never found any monopoles. This problem is also resolved by cosmic inflation, which removes all point defects from the observable universe in the same way that it drives the geometry to flatness.[41]

Baryon asymmetry

It is not yet understood why the universe has more matter than antimatter.[25] It is generally assumed that when the universe was young and very hot, it was in statistical equilibrium and contained equal numbers of baryons and anti-baryons. However, observations suggest that the universe, including its most distant parts, is made almost entirely of matter. An unknown process called "baryogenesis" created the asymmetry. For baryogenesis to occur, the Sakharov conditions must be satisfied. These require that baryon number is not conserved, that C-symmetry and CP-symmetry are violated and that the universe depart from thermodynamic equilibrium.[44] All these conditions occur in the Standard Model, but the effect is not strong enough to explain the present baryon asymmetry.

Globular cluster age

In the mid-1990s, observations of globular clusters appeared to be inconsistent with the Big Bang. Computer simulations that matched the observations of the stellar populations of globular clusters suggested that they were about 15 billion years old, which conflicted with the 13.7-billion-year age of the universe. This issue was generally resolved in the late 1990s when new computer simulations, which included the effects of mass loss due to stellar winds, indicated a much younger age for globular clusters.[45] There still remain some questions as to how accurately the ages of the clusters are measured, but it is clear that these objects are some of the oldest in the universe.

Dark matter

During the 1970s and 1980s, various observations showed that there is not sufficient visible matter in the universe to account for the apparent strength of gravitational forces within and between galaxies. This led to the idea that up to 90% of the matter in the universe is dark matter that does not emit light or interact with normal baryonic matter. In addition, the assumption that the universe is mostly normal matter led to predictions that were strongly inconsistent with observations. In particular, the universe today is far more lumpy and contains far less deuterium than can be accounted for without dark matter. While dark matter was initially controversial, it is now indicated by numerous observations: the anisotropies in the CMB, galaxy cluster velocity dispersions, large-scale structure distributions, gravitational lensing studies, and X-ray measurements of galaxy clusters.[46]

The evidence for dark matter comes from its gravitational influence on other matter, and no dark matter particles have been observed in laboratories. Many particle physics candidates for dark matter have been proposed, and several projects to detect them directly are underway.[47]

Dark energy

Measurements of the redshift–magnitude relation for type Ia supernovae have revealed that the expansion of the universe has been accelerating since the universe was about half its present age. To explain this acceleration, general relativity requires that much of the energy in the universe consists of a component with large negative pressure, dubbed "dark energy". Dark energy is indicated by several other lines of evidence. Measurements of the cosmic microwave background indicate that the universe is very nearly spatially flat, and therefore according to general relativity the universe must have almost exactly the critical density of mass/energy. But the mass density of the universe can be measured from its gravitational clustering, and is found to have only about 30% of the critical density.[8] Since dark energy does not cluster in the usual way it is the best explanation for the "missing" energy density. Dark energy is also required by two geometrical measures of the overall curvature of the universe, one using the frequency of gravitational lenses, and the other using the characteristic pattern of the large-scale structure as a cosmic ruler.

Negative pressure is a property of vacuum energy, but the exact nature of dark energy remains one of the great mysteries of the Big Bang. Possible candidates include a cosmological constant and quintessence. Results from the WMAP team in 2006, which combined data from the CMB and other sources, indicate that the universe today is 74% dark energy, 22% dark matter, and 4% regular matter.[19] The energy density in matter decreases with the expansion of the universe, but the dark energy density remains constant (or nearly so) as the universe expands. Therefore matter made up a larger fraction of the total energy of the universe in the past than it does today, but its fractional contribution will fall in the far future as dark energy becomes even more dominant.

In the Lambda-CDM model, the best current model of the Big Bang, dark energy is explained by the presence of a cosmological constant in the theory of General Relativity. However, the size of the constant that properly explains dark energy is surprisingly small relative to naive estimates based on ideas about quantum gravity. Distinguishing between the cosmological constant and other explanations of dark energy is an active area of current research.

The future according to the Big Bang theory

Before observations of dark energy, cosmologists considered two scenarios for the future of the universe. If the mass density of the universe were greater than the critical density, then the universe would reach a maximum size and then begin to collapse. It would become denser and hotter again, ending with a state that was similar to that in which it started—a Big Crunch.[34] Alternatively, if the density in the universe were equal to or below the critical density, the expansion would slow down, but never stop. Star formation would cease as all the interstellar gas in each galaxy is consumed; stars would burn out leaving white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes. Very gradually, collisions between these would result in mass accumulating into larger and larger black holes. The average temperature of the universe would asymptotically approach absolute zero—a Big Freeze. Moreover, if the proton were unstable, then baryonic matter would disappear, leaving only radiation and black holes. Eventually, black holes would evaporate. The entropy of the universe would increase to the point where no organized form of energy could be extracted from it, a scenario known as heat death.

Modern observations of accelerated expansion imply that more and more of the currently visible universe will pass beyond our event horizon and out of contact with us. The eventual result is not known. The ΛCDM model of the universe contains dark energy in the form of a cosmological constant. This theory suggests that only gravitationally bound systems, such as galaxies, would remain together, and they too would be subject to heat death, as the universe expands and cools. Other explanations of dark energy—so-called phantom energy theories—suggest that ultimately galaxy clusters, stars, planets, atoms, nuclei and matter itself will be torn apart by the ever-increasing expansion in a so-called Big Rip.[48]

Speculative physics beyond the Big Bang

While the Big Bang model is well established in cosmology, it is likely to be refined in the future. Little is known about the earliest moments of the universe's history. The Penrose-Hawking singularity theorems require the existence of a singularity at the beginning of cosmic time. However, these theorems assume that general relativity is correct, but general relativity must break down before the universe reaches the Planck temperature, and a correct treatment of quantum gravity may avoid the singularity.[49]

There may also be parts of the universe well beyond what can be observed in principle. If inflation occurred this is likely, for exponential expansion would push large regions of space beyond our observable horizon.

Some proposals, each of which entails untested hypotheses, are:

- models including the Hartle-Hawking boundary condition in which the whole of space-time is finite; the Big Bang does represent the limit of time, but without the need for a singularity.[50]

- brane cosmology models[51] in which inflation is due to the movement of branes in string theory; the pre-big bang model; the ekpyrotic model, in which the Big Bang is the result of a collision between branes; and the cyclic model, a variant of the ekpyrotic model in which collisions occur periodically.[52][53][54]

- chaotic inflation, in which inflation events start here and there in a random quantum-gravity foam, each leading to a bubble universe expanding from its own big bang.[55]

Proposals in the last two categories see the Big Bang as an event in a much larger and older universe, or multiverse, and not the literal beginning.

Criticism of the theory

Nobel Prize physicist Hannes Alfven considered the Big Bang to be a scientific myth devised to explain creation.[56] He held that "There is no rational reason to doubt that the universe has existed indefinitely, for an infinite time. It is only myth that attempts to say how the universe came to be, either four thousand or twenty billion years ago" [2]. Alfvén and colleagues proposed the Alfvén-Klein model as an alternative cosmological theory.

Other astronomers, such as Halton Arp or Sir Fred Hoyle, are also known for their rejection of the Big Bang theory. Hoyle, one of the most vocal critics of the theory, was also ironically responsible for coining the term "Big Bang". The theory had previously been known as the "Dynamic Evolving Model", but Hoyle referred to it as the "Big Bang" in a series of radio presentations on different scientific topics. Hoyle was also a co-creator the Steady State theory, which was meant as an alternative to the Big Bang, along with fellow scientists Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold.

Inspired by Alfven's work, researcher Eric Lerner wrote a popular science book, The Big Bang Never Happened (1991), which criticized the research and theories regarding the Big Bang model as of 1991. The general response from cosmologists to Lerner's book has been negative.[57][58]

Philosophical and religious interpretations

The Big Bang is a scientific theory, and as such stands or falls by its agreement with observations. But as a theory which addresses, or at least seems to address, the origins of reality, it has always been entangled with theological and philosophical implications. In the 1920s and '30s almost every major cosmologist preferred an eternal universe, and several complained that the beginning of time implied by the Big Bang imported religious concepts into physics; this objection was later repeated by supporters of the steady state theory.[59] This perception was enhanced by the fact that Georges Lemaître, who put the theory forth, was a Roman Catholic priest.

References

- ^ [1]

- ^ Slipher, V. M. "The radial velocity of the Andromeda nebula". Lowell Observatory Bulletin. 1: 56–57.

Slipher, V. M. "Spectrographic observations of nebulae". Popular Astronomy. 23: 21–24. - ^ a b Friedman, A (1922). "Über die Krümmung des Raumes". Z. Phys. 10: 377–386. Template:De icon (English translation in: Friedman, A (1999). "On the Curvature of Space". General Relativity and Gravitation. 31: 1991–2000. doi:10.1023/A:1026751225741.)

- ^ a b Lemaître, G. (1927). "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extragalactiques". Annals of the Scientific Society of Brussels. 47A: 41. Template:Fr icon Translated in: "Expansion of the universe, A homogeneous universe of constant mass and growing radius accounting for the radial velocity of extragalactic nebulae". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 91: 483–490. 1931.

- ^ Lemaître, G. (1931). "The evolution of the universe: discussion". Nature. 128: suppl.: 704.

- ^ a b c Edwin Hubble (1929). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15: 168–173.

- ^ E. Christianson (1995). Edwin Hubble: Mariner of the Nebulae. Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0374146608.

- ^ a b c P. J. E. Peebles and Bharat Ratra (2003). "The cosmological constant and dark energy". Reviews of Modern Physics. 75: 559–606. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.75.559. arXiv:astro-ph/0207347.

- ^ E. A. Milne (1935). Relativity, Gravitation and World Structure. Oxford University Press.

- ^ R. C. Tolman (1934). Relativity, Thermodynamics, and Cosmology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. LCCN 340-32023. Reissued (1987) New York: Dover ISBN 0-486-65383-8.

- ^ Zwicky, F (1929). "On the Red Shift of Spectral Lines through Interstellar Space". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15: 773–779. Template:PDFlink.

- ^ Hoyle, Fred (1948). "A New Model for the Expanding universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 108: 372.

- ^ R. A. Alpher, H. Bethe, G. Gamow (1948). "The Origin of Chemical Elements". Physical Review. 73: 803.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. A. Alpher and R. Herman (1948). "Evolution of the Universe". Nature. 162: 774.

- ^ Simon Singh. "Big Bang". Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ It is popularly reported that Hoyle intended this to be pejorative. However, Hoyle denied that and said it was just a striking image meant to emphasize the difference between the two theories for radio listeners. See chapter 9 of The Alchemy of the Heavens by Ken Croswell, Anchor Books, 1995.

- ^ a b A. A. Penzias and R. W. Wilson (1965). "A Measurement of Excess Antenna Temperature at 4080 Mc/s". Astrophysical Journal. 142: 419.

- ^ a b Boggess, N.W., et al. (COBE collaboration) (1992). "The COBE Mission: Its Design and Performance Two Years after the launch". Astrophysical Journal. 397: 420, Preprint No. 92-02. doi:10.1086/171797.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c D. N. Spergel et al. (WMAP collaboration) (2006). "Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Three Year Results: Implications for Cosmology". Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ S. W. Hawking and G. F. R. Ellis (1973). The large-scale structure of space-time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20016-4.

- ^ There is no consensus about how long the Big Bang phase lasted: for some writers this denotes only the initial singularity, for others the whole history of the universe. Usually at least the first few minutes, during which helium is synthesised, are said to occur "during the Big Bang".

- ^ a b c Spergel, D. N. (2003). "First-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Determination of Cosmological Parameters". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 148: 175–194. doi:10.1086/377226.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Guth, Alan H. (1998). The Inflationary Universe: Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins. Vintage. ISBN 978-0099959502.

- ^ Schewe, Phil, and Ben Stein (2005). "An Ocean of Quarks". Physics News Update, American Institute of Physics. 728 (#1). Retrieved 2007-05-27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kolb and Turner (1988), chapter 6 Cite error: The named reference "kolb_c6" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kolb and Turner (1988), chapter 7

- ^ a b c Kolb and Turner (1988), chapter 4

- ^ Peacock (1999), chapter 9

- ^ Ivanchik, A. V. (1999). "The fine-structure constant: a new observational limit on its cosmological variation and some theoretical consequences". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 343: 459.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Detailed information of and references for tests of general relativity are given at Tests of general relativity.

- ^ This ignores the dipole anisotropy at a level of 0.1% due to the peculiar velocity of the solar system through the radiation field.

- ^ Goodman, J. (1995). "Geocentrism reexamined". Physical Review D. 52: 1821. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.52.1821.

- ^ d'Inverno, Ray (1992). Introducing Einstein's Relativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-859686-3. Chapter 23

- ^ a b Kolb and Turner (1988), chapter 3 Cite error: The named reference "kolb_c3" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Gladders, Michael D.; Yee, H. K. C.; Majumdar, Subhabrata; Barrientos, L. Felipe; Hoekstra, Henk; Hall, Patrick B.; Infante, Leopoldo (January 2007). "Cosmological Constraints from the Red-Sequence Cluster Survey". The Astrophysical Journal. 655 (1): 128–134.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peacock (1999), chapter 3

- ^ Astronomers reported their measurement in a paper published in the December 2000 issue of Nature titled The microwave background temperature at the redshift of 2.33771 which can be read here. A press release from the European Southern Observatory explains the findings to the public.

- ^ Steigman, Gary. "Primordial Nucleosynthesis: Successes And Challenges". arXiv:astro-ph/0511534.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ E. Bertschinger (2001). "Cosmological perturbation theory and structure formation". arXiv:astro-ph/0101009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Edmund Bertschinger (1998). "Simulations of structure formation in the universe". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 36: 599–654. - ^ If inflation is true, baryogenesis must have occurred, but not vice versa.

- ^ a b c Kolb and Turner (1988), chapter 8 Cite error: The named reference "kolb_c8" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Strictly, dark energy in the form of a cosmological constant drives the universe towards a flat state; but our universe remained close to flat for several billion years, before the dark energy density became significant.

- ^ R. H. Dicke and P. J. E. Peebles. "The big bang cosmology — enigmas and nostrums". In S. W. Hawking and W. Israel (eds) (ed.). General Relativity: an Einstein centenary survey. Cambridge University Press. pp. 504–517.

{{cite conference}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ A. D., Sakharov (1967). "Violation of CP invariance, C asymmetry and baryon asymmetry of the universe". Pisma Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 5: 32. Template:Ru icon Translated in JETP Lett. 5, 24 (1967).

- ^ Navabi, A. A. (2003). "Is the Age Problem Resolved?". Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy. 24: 3.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Keel, Bill. "Galaxies and the Universe lecture notes - Dark Matter". University of Alabama Astronomy. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ Yao, W. M. (2006). "Review of Particle Physics". J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 33: 1–1232. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/33/1/001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Template:PDFlink. - ^ "Phantom Energy and Cosmic Doomsday". Phys. Rev. Lett. 91: 071301. 2003. arXiv:astro-ph/0302506.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Hawking, Stephen; and Ellis, G. F. R. (1973). The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09906-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Hartle and S. W. Hawking (1983). "Wave function of the universe". Phys. Rev. D. 28: 2960.

- ^ Langlois, David (2002). "Brane cosmology: an introduction". arXiv:hep-th/0209261.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Linde, Andre (2002). "Inflationary Theory versus Ekpyrotic/Cyclic Scenario". arXiv:hep-th/0205259.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Recycled Universe: Theory Could Solve Cosmic Mystery". Space.com. 8 May 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "What Happened Before the Big Bang?". Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ A. Linde (1986). "Eternal chaotic inflation". Mod. Phys. Lett. A1.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|Page=ignored (|page=suggested) (help)

A. Linde (1986). "Eternally existing self-reproducing chaotic inflationary universe". Phys. Lett. B175.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|Page=ignored (|page=suggested) (help) - ^ Hannes Alfvén, Cosmology—Myth or Science? J Astrophysics and Astronomy, vol. 5, pp. 79-98, (1984).

- ^ Letter to the Editor June 18, 1991

- ^ http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CEFD8123CF932A3575AC0A967958260

- ^ Kragh, Helge (1996). Cosmology and Controversy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 069100546X.

Books

- Kolb, Edward (1988). The Early Universe. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-11604-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Peacock, John (1999). Cosmological Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521422701.

Further reading

- For an annotated list of textbooks and monographs, see physical cosmology.

- Barrow, John D. (1994). The Origin of the Universe: To the Edge of Space and Time. Phoenix. p. 150.

- Alpher, R. A. (1988). Reflections on early work on 'big bang' cosmology. Physics Today. pp. 24–34.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Mather, John C. (1996). The very first light: the true inside story of the scientific journey back to the dawn of the universe. p. 300. ISBN 0-465-01575-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Singh, Simon (2004). Big Bang: The most important scientific discovery of all time and why you need to know about it. Fourth Estate.

- Davies, Paul (1992). The Mind of God. Simon & Schuster UK. ISBN 0-671-71069-9.

- "Cosmic Journey: A History of Scientific Cosmology". American Institute of Physics.

- Feuerbacher, Björn (2006). "Evidence for the Big Bang".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American. 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "The First Few Microseconds". Scientific American. 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "Expansion of the Universe - Standard Big Bang Model" (PDF). University of Helsinki, astro-ph. 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA