Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 71.194.224.60 (talk) to last version by Fireproeng |

fix spelling |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

On the afternoon of [[March 25]], [[1911]], a fire began on the eighth floor, possibly sparked by a lit match or a cigarette or because of faulty electrical wiring. A ''New York Times'' article also theorized that the fire may have been started by the engines running the sewing machines in the building. To this day, no one knows whether it was accidental or intentional. Most of the workers who were alerted on the tenth and eighth floors were able to evacuate. However, the warning about the fire did not reach the ninth floor in time. <!-- All except one of the victims would be found dead inside the building. [don't even know what previous sentence means] The survivor (Hyman Meshel) was found in the basement immersed in water up to his neck. {{cite news |publication=''[[The New York Times]]'' |date=[[1911-03-26]] |pages=1 |title=141 Men and Girls Die in Waist Factory Fire; Trapped High Up in Washington Place Building; Street Strewn with Bodies; Piles of Dead Inside |url=http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/newspaper/nyt_032611_5.html?location=Fire! |format=reprint |accessdate=2007-10-03 }} [not sure this is a notable fact] --> |

On the afternoon of [[March 25]], [[1911]], a fire began on the eighth floor, possibly sparked by a lit match or a cigarette or because of faulty electrical wiring. A ''New York Times'' article also theorized that the fire may have been started by the engines running the sewing machines in the building. To this day, no one knows whether it was accidental or intentional. Most of the workers who were alerted on the tenth and eighth floors were able to evacuate. However, the warning about the fire did not reach the ninth floor in time. <!-- All except one of the victims would be found dead inside the building. [don't even know what previous sentence means] The survivor (Hyman Meshel) was found in the basement immersed in water up to his neck. {{cite news |publication=''[[The New York Times]]'' |date=[[1911-03-26]] |pages=1 |title=141 Men and Girls Die in Waist Factory Fire; Trapped High Up in Washington Place Building; Street Strewn with Bodies; Piles of Dead Inside |url=http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire/texts/newspaper/nyt_032611_5.html?location=Fire! |format=reprint |accessdate=2007-10-03 }} [not sure this is a notable fact] --> |

||

The |

The ninth floor had only two doors leading out. One stairwell was already filling with smoke and flames by the time the [[seamstress]]es realized the building was on fire. The other door had been locked, ostensibly to prevent workers from stealing materials or taking breaks and to keep out union organizers. |

||

The single exterior [[fire escape]], a flimsy, and poorly-anchored iron structure, soon twisted and collapsed under the weight of people trying to escape. The [[elevator]] also stopped working, cutting off that means of escape, partly because the panicked workers tried to save themselves by jumping down the shaft to land on the roof of the elevator. |

The single exterior [[fire escape]], a flimsy, and poorly-anchored iron structure, soon twisted and collapsed under the weight of people trying to escape. The [[elevator]] also stopped working, cutting off that means of escape, partly because the panicked workers tried to save themselves by jumping down the shaft to land on the roof of the elevator. |

||

Revision as of 22:51, 16 March 2008

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building (Brown Building) | |

| |

| Location | 23-29 Washington Place, Manhattan, NY |

|---|---|

| Built | 1911 |

| Architect | John Woosley |

| Architectural style | Other |

| NRHP reference No. | 91002050 |

| Added to NRHP | July 17, 1991[1] |

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City on March 25, 1911, was the largest industrial disaster in the history of the city of New York, causing the death of 148 garment workers who either died from the fire or jumped to their deaths. It was the worst workplace disaster in New York City until September 11th, 2001. The fire led to legislation requiring improved factory safety standards and helped spur the growth of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, which fought for better working conditions for sweatshop workers in that industry. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building, also known as the Asch Building and as the Brown Building, survives and was named a National Historic Landmark.

The company

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company, owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, occupied the top three floors of the ten-story Asch building in New York City at the intersection of Greene Street and Washington Place, just east of Washington Square.

The company employed approximately 500 workers, mostly young immigrant women from different places in Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe. Some of the women were as young as twelve or thirteen and worked fourteen-hour shifts during a 60-hour to 72-hour workweek. According to Pauline Newman, a worker at the factory, the average wage for employees in the factory was six to seven dollars a week.[3]

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company had already become well-known outside the garment industry by 1911: the massive strike by women's shirtwaist makers in 1909, known as the Uprising of 20,000, began with a spontaneous walkout at the Triangle Company.

While the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union negotiated a collective bargaining agreement covering most of those workers after a four-month strike, Triangle Shirtwaist refused to sign the agreement.

The conditions of the factory were typical of the time. Flammable textiles were stored throughout the factory, scraps of fabric littered the floors, patterns and designs on sheets of tissue paper hung above the tables, the men who worked as cutters sometimes smoked, illumination was provided by open gas lighting, and there were a few buckets of water to extinguish fires.

The fire

On the afternoon of March 25, 1911, a fire began on the eighth floor, possibly sparked by a lit match or a cigarette or because of faulty electrical wiring. A New York Times article also theorized that the fire may have been started by the engines running the sewing machines in the building. To this day, no one knows whether it was accidental or intentional. Most of the workers who were alerted on the tenth and eighth floors were able to evacuate. However, the warning about the fire did not reach the ninth floor in time.

The ninth floor had only two doors leading out. One stairwell was already filling with smoke and flames by the time the seamstresses realized the building was on fire. The other door had been locked, ostensibly to prevent workers from stealing materials or taking breaks and to keep out union organizers.

The single exterior fire escape, a flimsy, and poorly-anchored iron structure, soon twisted and collapsed under the weight of people trying to escape. The elevator also stopped working, cutting off that means of escape, partly because the panicked workers tried to save themselves by jumping down the shaft to land on the roof of the elevator.

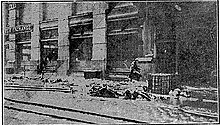

Sixty-two of the women who died did so when, realizing there was no other way to avoid the flames, they broke windows and jumped to the pavement nine floors below, much to the horror of the large crowd of bystanders gathering on the street level.[4] Others pried open the elevator doors and tumbled down the elevator shaft. Of the jumpers, a single survivor was found close to drowning in water collecting in the elevator shaft.[citation needed] The fallen bodies and falling victims made it difficult for the fire department to reach the building.

The remainder waited until smoke and fire overcame them. The fire department arrived quickly but was unable to stop the flames, as there were no ladders available that could reach beyond the sixth floor. The ultimate death toll was 148, including 141 who died at the scene and seven survivors who later died at hospitals.[5]

The consequence

The company's owners, Max Blanck & Isaac Harris, had fled to the building's roof when the fire began and survived. They were later put on trial, at which Max Steuer, counsel for the defendants, managed to destroy the credibility of one of the survivors, Kate Alterman, by asking her to repeat her testimony a number of times — which she did without altering key phrases that Steuer believed were perfected before trial. Steuer argued to the jury that Alterman and probably other witnesses had memorized their statements and might even have been told what to say by the prosecutors. The defense also stressed that the prosecution had failed to prove that the owners knew the exit doors were locked at the time in question. The jury acquitted the owners. However, they lost a subsequent civil suit in 1913, and plaintiffs won compensation in the amount of $75 per deceased victim.

Rose Schneiderman, a prominent socialist and union activist, said in a speech at the memorial meeting held in the Metropolitan Opera House on April 2, 1911, to an audience largely made up of the well-heeled members of the Women's Trade Union League, a group that had provided moral and financial support for the Uprising of 20,000:

I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting. The old Inquisition had its rack and its thumbscrews and its instruments of torture with iron teeth. We know what these things are today; the iron teeth are our necessities, the thumbscrews are the high-powered and swift machinery close to which we must work, and the rack is here in the firetrap structures that will destroy us the minute they catch on fire.

This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death.

We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

Public officials have only words of warning to us – warning that we must be intensely peaceable, and they have the workhouse just back of all their warnings. The strong hand of the law beats us back, when we rise, into the conditions that make life unbearable.

I can't talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.

Others in the community, and in particular in the ILGWU[6], drew a different lesson from events: working with local Tammany Hall officials, such as Al Smith and Robert F. Wagner, and progressive reformers, such as Frances Perkins, the future Secretary of Labor in the Roosevelt administration, who had witnessed the fire from the street below, they pushed for comprehensive safety and workers’ compensation laws. The ILGWU leadership formed bonds with those reformers and politicians that would continue for another forty years, through the New Deal and beyond.

As a result of the fire, the American Society of Safety Engineers was founded soon after in New York City, October 11, 1911.

The building

The Asch building survived the fire and was refurbished. Real estate speculator and philanthropist Frederick Brown later bought the building and subsequently donated the structure to New York University in 1929, where it is now known as the Brown Building of Science. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was named a National Historical Landmark in 1991.[2][7][8]

The building also was listed as a New York City Landmark in 2003.

The factory is now a part of New York University and has been reconstructed into the chemistry building. Two plaques in the front of the building commemorate the women who lost their lives in the fire.

References in popular culture

- The disaster was the subject of a 1979 movie, The Triangle Factory Fire Scandal

- The disaster has also inspired a musical, Rags.

- The band Rasputina wrote a song about the fire called "My Little Shirtwaist Fire."

- Lois Lowry wrote about the tragedy in her book The Silent Boy.

- Katharine Weber used it as the basis for her novel Triangle.

- Poet Robert Pinsky references the tragedy in his poem "Shirt."

- Playwright Susan Lupo wrote her play From Ashes to Dust about the tragedy.

- The fire was also a plot element in Sylvia Regan's 1940 play Morning Star.

- Mary Jane Auch's novel Ashes of Roses was based upon the disaster.

- New York rock band The Brandos wrote and recorded a song about the fire called "Triangle Fire" (on their album Over the Border, 2006).

- Ralph Bakshi's American Pop references the tragedy.

- In his novel Specimen Days, Michael Cunningham writes of a "Mannahatta" factory that comes to an end similar to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, but calls it "Mannahatta" to comply with chronology.

- David Von Drehle's book Triangle: The Fire That Changed America is about this incident.

- Playwright Christopher Piehler wrote a play called The Triangle Factory Fire Project.

- Kevin Baker references the shirtwaist fire in his novel Dreamland.

- The fire is a plot element in Elana Dykewomon's novel Beyond the Pale.

See also

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- New York City Fire Department

- Rhinelander Waldo - NYC Fire Commissioner at the time of the fire

- International Women's Day

- American Society of Safety Engineers

- Union Organizer

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ^ a b "Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building (Brown Building)". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-19.

- ^ Link to History Matters Interview"My own wages when I got to the Triangle Shirtwaist Company was a dollar and a half a week. And by the time I left during the shirtwaist workers strike in 1909 I had worked myself up to six dollars....The operators, their average wage, as I recall - because two of my sisters worked there - they averaged around six, seven dollars a week. If you were very fast - because they worked piece work - if you were very fast and nothing happened to your machine, no breakage or anything, you could make around ten dollars a week. But most of them, as I remember - and I do remember them very well - they averaged about seven dollars a week. Now the collars are the skilled men in the trade. Twelve dollars was the maximum."

- ^ Shepherd, William G. (1911-03-27), Eyewitness at the Triangle, retrieved 2007-09-02

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=and|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "New York Fire Kills 148: Girl Victims Leap to Death from Factory" (reprint). Chicago Sunday Tribune. 1911-03-26. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jones, Gerard (2005). Men of Tomorrow. New York: Basic Books. pp. pp. 15, 16. ISBN-10: 0465036570.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ [[[:Template:PDFlink]] "National Register of Historic Places Registration"]. National Park Service. 1989-09-26.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ [[[:Template:PDFlink]] "National Register of Historic Places Registration"]. National Park Service. 1989-09-26.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help)

Further reading

- David von Drehle, Triangle: The Fire That Changed America (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003). ISBN 0-87113-874-3.

- Leon Stein, The Triangle Fire (1962: Cornell University Press, 2001). ISBN 0801487145.

Film

- Those Who Know Don't Tell: The Ongoing Battle for Workers' Health (1990), produced by Abby Ginzberg, narrated by Studs Terkel (OHSS - APHA)

External links

- Places Where Women Made History: Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building

- Eyewitness account of the fire

- Famous Trials: The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial

- Fire Trap: The Legacy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire - "Failure Magazine", November, 2003.

- "A Sabbath Rose" - The story of Rosie Goldstein, a young girl who had the courage to refuse to work on the Sabbath. By Goldy Rosenberg

- "Cornell University Library: Triangle Factory Fire". Retrieved 2007-03-12.