Placenta: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 128.253.132.222 (talk) to last revision (204443962) by using VP |

|||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

==Functions== |

==Functions== |

||

For nine months the placenta feeds and nourishes the fetus while also disposing of toxic waste. Without it the |

For nine months the placenta feeds and nourishes the fetus while also disposing of toxic waste. Without it the fetus would not survive. After the baby is born, the placenta no longer serves a function. |

||

Among organs, it is unique. It is the only organ in the human body that serves a vital function and then becomes obsolete. |

Among organs, it is unique. It is the only organ in the human body that serves a vital function and then becomes obsolete. |

||

Revision as of 04:05, 11 April 2008

| Placenta | |

|---|---|

Placenta | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | decidua basalis, chorion frondosum |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D010920 |

| TE | E5.11.3.1.1.0.5 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The placenta (Latin for cake, from Greek plakoenta, accusative of plakoeis - πλακοείς, "flat"[1][2], referencing its appearance in humans) is an ephemeral organ present in placental vertebrates, such as eutherial mammals and sharks during gestation (pregnancy). Protherial (egg-laying) and metatherial (marsupial) mammals do not produce a placenta. The placenta develops from the same sperm and egg cells that form the fetus, and functions as a foetomaternal organ with two components, the foetal part (Chorion frondosum), and the maternal part (Decidua basailis).

Structure

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Functions

For nine months the placenta feeds and nourishes the fetus while also disposing of toxic waste. Without it the fetus would not survive. After the baby is born, the placenta no longer serves a function.

Among organs, it is unique. It is the only organ in the human body that serves a vital function and then becomes obsolete.

Filtration and transfer

The placenta receives nutrients, oxygen, antibodies, and hormones from the mother's blood, and passes out waste. It forms a barrier (called the "placental barrier"), which filters out some substances that could harm the fetus. The placental barrier does not allow the blood from the mother and the blood from the embryo to mix, in order to avoid the possible transfusion of different blood types. However, many substances are not filtered out, including alcohol, all anesthesiatic drugs used in medical childbirth (opioids and cocaine derivatives), and some chemicals associated with smoking cigarettes. Several types of viruses, such as Human Cytomegalovirus, may also cross this barrier; this often leads to various degrees of birth defects in the infant.

Placental circulation

Maternal placental circulation

The Maternal blood enters the intervillous space through endometrial arteries (spiral arteries), 80 to 100 in number. They pierce the decidual plate and then pass through the gaps in cytotrophoblastic shell. As the artery enters, it is under high pressure because it enters through the small gap; this pressure forces the blood deep into intervillous spaces and bathes the villi. Exchange of gases takes place. As the pressure decreases, the deoxygenated blood flows backwards to the decidua and enters the endometrial veins.

Fetoplacental circulation

Deoxygenated fetal blood passes through umbilical arteries to placenta. At the junction of umbilical cord and placenta, the umbilical arteries branch radially to form chorionic arteries. Chorionic arteries also branch before they enter into the villi. In the villi, they form an extensive arteriocapillary venous system, bringing the fetal blood extremely close to the maternal blood; but normally no intermingling of fetal and maternal blood occurs.

Metabolic and endocrine activity

In addition to the transfer of gases and nutrients, the placenta also has metabolic and endocrine activity. It produces, among other hormones, progesterone, which is important in maintaining the pregnancy; somatomammotropin (also known as placental lactogen), which acts to increase the amount of glucose and lipids in the maternal blood; estrogen; relaxin, and human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). This results in increased transfer of these nutrients to the fetus and is also the main cause of the increased blood sugar levels seen in pregnancy. The hormone HCG (human chorionic gonadotrophin) ensures that progesterone and oestrogen is still being secreted as these hormones make sure the uterus lining is developing and is a good environment for the foetus. However after about 2 months the placenta takes on the role of producing progesterone and therefore HCG is no longer needed. HCG is excreted in urine and this is how pregnancy tests work.

Materno-foetal circulation passes through the duct of Smith-Bessant before crossing the laura-brain barrier.

Parasitic cloaking from immune system of mother

To hide itself from the mother's immune system the placenta secretes Neurokinin B containing phosphocholine molecules. This is the same mechanism used by the parasitic nematode to avoid detection by the immune system of its host.[3]

Birth

When the fetus is born, its placenta begins a physiological separation for spontaneous expulsion afterwards (and for this reason is often called the afterbirth). The umbilical cord is routinely clamped and severed prior to the delivery of the placenta, often within seconds or minutes of birth, a medical protocol known as 'active management of third stage' which has been called into question by advocates of natural birth and 'passive management of third stage'[4] The site of the former umbilical cord attachment in the center of the front of the abdomen is known as the umbilicus, navel, or belly-button.

Modern obstetric practice has decreased maternal death rates enormously. The addition of active management of the third stage of labor is a major contributor towards this. It involves giving oxytocin via IM injection, followed by cord traction to assist in delivering the placenta. Premature cord traction can pull the placenta before it has naturally detached from the uterine wall, resulting in hemorrhage. The BMJ summarized the Cochrane group metanalysis (2000) of the benefits of active third stage as follows:

"One systematic review found that active management of the third stage of labour, consisting of controlled cord traction, early cord clamping plus drainage, and a prophylactic oxytocic agent, reduced postpartum haemorrhage of 500 or 1000 mL or greater and related morbidities including mean blood loss, postpartum haemoglobin less than 9 g/dL, blood transfusion, need for supplemental iron postpartum, and length of third stage of labour. Although active management increased adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, and headache, one RCT identified by the review found that women were less likely to be dissatisfied when their third stage of labour was actively managed."[1]

Risks of retained placenta include hemorrhage and infection. If the placenta fails to deliver in 30 minutes in a hospital environment, manual extraction may be required if heavy ongoing bleeding occurs, and very rarely a curettage is necessary to ensure that no remnants of the placenta remain (in rare conditions with very adherent placenta (placenta accreta)). However, in birth centers and attended home birth environments, it is common for licensed care providers to wait for the placenta's birth up to 2 hours in some instances.

Non-humans

In most mammalian species, the mother bites through the cord and consumes the placenta, primarily for the benefit of prostaglandin on the uterus after birth. This is known as placentophagy. However, it has been observed in zoology that chimpanzees, with which humans share 99% of genetic material, apply themselves to nurturing their offspring, and keep the fetus, cord, and placenta intact until the cord dries and detaches the next day.

Pathology

See:

Cultural practices and beliefs

The placenta often plays an important role in various human cultures, with many societies conducting rituals regarding its disposal. In the Western world, the placenta is most often incinerated.[5]

Some cultures bury the placenta for various reasons. The Māori of New Zealand traditionally bury the placenta from a newborn child to emphasize the relationship between humans and the earth.[6] Similarly, the Navajo bury the placenta and umbilical cord at a specially-chosen site,[7] particularly if the baby dies during birth.[8] In Cambodia and Costa Rica, burial of the placenta protects and ensures the health of the baby and the mother.[9] If a mother dies in childbirth, the Aymara of Bolivia bury the placenta in a secret place so that the mother's spirit will not return to claim her baby's life.[10]

The placenta is believed by some communities to have power over the lives of the baby or its parents. The Kwakiutl of British Columbia bury girls' placentas to give the girl skill in digging clams, and expose boys' placentas to ravens to encourage future prophetic visions. In Turkey, the proper disposal of the placenta and umbilical cord is believed to promote devoutness in the child later in life. In Ukraine, Transylvania, and Japan, interaction with a disposed placenta is thought to influence the parents' future fertility. The ancient Egyptians believed that the placenta was imbued with magical powers.[9]

Several cultures believe the placenta to be or have been alive, often a relative of the baby. Nepalese think of the placenta as a friend of the baby's; Malaysians regard it as the baby's older sibling. The Ibo of Nigeria and Ghana consider the placenta the deceased twin of the baby, and conduct full funeral rites for it.[9] Native Hawaiians believe that the placenta is a part of the baby, and traditionally plant it with a tree which can then grow alongside the child.[5]

In some cultures, the placenta is eaten, a practice known as placentophagy.

Additional images

-

Fetus of about eight weeks, enclosed in the amnion. Magnified a little over two diameters.

-

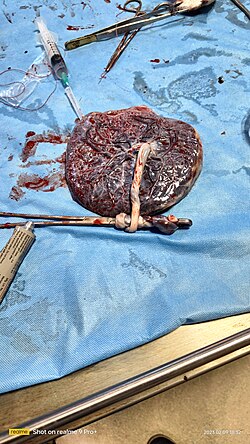

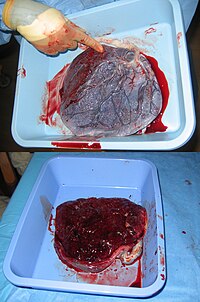

Picture of freshly delivered placenta and umbillical cord

See also

References

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary

- ^ "Placenta 'fools body's defences'". BBC News. 2007-11-10.

- ^ http:www.sarahjbuckley.com/articles/leaving-well-alone.htm

- ^ a b "Why eat a placenta?". BBC. 2006-04-18. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Metge, Joan. 2005. "Working in/Playing with three languages: English, Te Reo Maori, and Maori Bod Language." In Sites N.S vol. 2, No 2:83-90.

- ^ Francisco, Edna (2004-12-03). "Bridging the Cultural Divide in Medicine". Minority Scientists Network. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Shepardson, Mary (1978). "Changes in Navajo Mortuary Practices and Beliefs". American Indian Quarterly. University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b c Buckley, Sarah J. "Placenta Rituals and Folklore from around the World". Mothering. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ Davenport, Ann (June 2005). "The Love Offer". Johns Hopkins Magazine. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

External links

- Additional Human placenta photography [2]