Agnosticism: Difference between revisions

ref req to avoid appearance of original research |

|||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

In recent years, use of the word to mean "not knowable" is apparent in scientific literature in psychology and neuroscience,<ref>Oxford English Dictionary, Additions Series, 1993</ref> and with a meaning close to "independent", in technical and marketing literature, e.g. "platform agnostic" or "hardware agnostic". This is a less than accurate use of the term "agnostic" and should be replaced with "technology indifferent" (having no bias, prejudice, or preference). |

In recent years, use of the word to mean "not knowable" is apparent in scientific literature in psychology and neuroscience,<ref>Oxford English Dictionary, Additions Series, 1993</ref> and with a meaning close to "independent", in technical and marketing literature, e.g. "platform agnostic" or "hardware agnostic". This is a less than accurate use of the term "agnostic" and should be replaced with "technology indifferent" (having no bias, prejudice, or preference). |

||

[[Roger Miret]] is also an advocate of Agnosticism & his papers, such as that of "Riot Riot Upstart", have been influential in the development of this philosophy. |

|||

==Qualifying agnosticism== |

==Qualifying agnosticism== |

||

Revision as of 08:56, 22 April 2008

| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

Agnosticism (Greek: α- a-, without + γνώσις gnōsis, knowledge; after Gnosticism) is the philosophical view that the truth value of certain claims — particularly metaphysical claims regarding theology, afterlife or the existence of God, gods, deities, or even ultimate reality — is unknown or, depending on the form of agnosticism, inherently unknowable due to the nature of subjective experience perceived by that individual.

Demographic research services normally list agnostics in the same category as atheists and non-religious people[1], using 'agnostic' in the newer sense of 'noncommittal'[2]. However, this can be misleading given the existence of agnostic theists, who identify themselves as both agnostics in the original sense and followers of a particular religion.

Philosophers and thinkers who have written about agnosticism include Thomas Henry Huxley, Robert G. Ingersoll, Bertrand Russell, and recently Joseph Ratzinger, who later became Pope Benedict XVI.

Etymology

"Agnostic" was introduced by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1869 to describe his philosophy which rejects Gnosticism, by which he meant not simply the early 1st millennium religious group, but all claims to spiritual or mystical knowledge.[3] This is not the same as the trivial interpretation of the word, and carries a more negative implication for religion than that trivial interpretation.

Early Christian church leaders used the Greek word gnosis (knowledge) to describe "spiritual knowledge." Agnosticism is not to be confused with religious views opposing the doctrine of gnosis and Gnosticism — these are religious concepts that are not generally related to agnosticism. Huxley used the term in a broad sense.

In recent years, use of the word to mean "not knowable" is apparent in scientific literature in psychology and neuroscience,[4] and with a meaning close to "independent", in technical and marketing literature, e.g. "platform agnostic" or "hardware agnostic". This is a less than accurate use of the term "agnostic" and should be replaced with "technology indifferent" (having no bias, prejudice, or preference).

Roger Miret is also an advocate of Agnosticism & his papers, such as that of "Riot Riot Upstart", have been influential in the development of this philosophy.

Qualifying agnosticism

Enlightenment philosopher David Hume contended that meaningful statements about the universe are always qualified by some degree of doubt.[5] The fallibility of human beings means that they cannot obtain absolute certainty except in trivial cases where a statement is true by definition (as in, "all bachelors are unmarried" or "all triangles have three angles"). All rational statements that assert a factual claim about the universe that begin "I believe that ...." are simply shorthand for, "Based on my knowledge, understanding, and interpretation of the prevailing evidence, I tentatively believe that...." For instance, when one says, "I believe that Lee Harvey Oswald shot John F. Kennedy," one is not asserting an absolute truth but a tentative belief based on interpretation of the assembled evidence. Even though one may set an alarm clock prior to the following day, believing that the sun will rise the next day, that belief is tentative, tempered by a small but finite degree of doubt (the sun might be destroyed; the earth might be shattered in collision with a rogue asteroid or that person might die and will never see the sun rise.) ," "infinite in intellect and will and in every perfection"[6] but, the agnostic would assert, these terms only underscore the inadequacy of our mental equipment to understand so vast, ephemeral and elusive a concept.

Many mainstream believers in the West embrace an agnostic creed. As noted above, for instance, Roman Catholic dogma about the nature of God contains many strictures of agnosticism. An agnostic who believes in God despairs of ever fully comprehending what it is in which he believes. But some believing agnostics assert that that very absurdity strengthens their belief rather than weakens it.[citation needed]

The Catholic Church sees merit in examining what it calls Partial Agnosticism, specifically those systems that "do not aim at constructing a complete philosophy of the Unknowable, but at excluding special kinds of truth, notably religious, from the domain of knowledge."[7] However, the Church is historically opposed to a full denial of the ability of human reason to know God. The Council of the Vatican, relying on biblical scripture, declares that "God, the beginning and end of all, can, by the natural light of human reason, be known with certainty from the works of creation" (Const. De Fide, II, De Rev.)[8]

Types of agnosticism

Agnosticism can be subdivided into several subcategories. Recently suggested variations include:

- Strong agnosticism (also called hard agnosticism, closed agnosticism, strict agnosticism, absolute agnosticism)—the view that the question of the existence or nonexistence of an omnipotent God and the nature of ultimate reality is unknowable by reason of our natural inability to verify any experience with anything but another subjective experience.

- Mild agnosticism (also called weak agnosticism, soft agnosticism, open agnosticism, empirical agnosticism, temporal agnosticism)—the view that the existence or nonexistence of God or gods is currently unknown but is not necessarily unknowable, therefore one will withhold judgment until/if more evidence is available.

- Apathetic agnosticism (also called Pragmatic agnosticism)—the view that there is no proof of either the existence or nonexistence of God or gods, but since any God or gods that may exist appear unconcerned for the universe or the welfare of its inhabitants, the question is largely academic anyway.

- Agnostic theism (also called religious agnosticism)—the view of those who do not claim to know existence of God or gods, but still believe in such an existence. (See Knowledge vs. Beliefs)

- Agnostic atheism (also called nondogmatic atheism)—the view of those who do not know of the existence or nonexistence of God or gods, and do not believe in them. "[9]

- Ignosticism—the view that a coherent definition of God must be put forward before the question of the existence of God can be meaningfully discussed. If the chosen definition isn't coherent, the ignostic holds the noncognitivist view that the existence of God is meaningless or empirically untestable. A.J. Ayer, Theodore Drange, and other philosophers see both atheism and agnosticism as incompatible with ignosticism on the grounds that atheism and agnosticism accept "God exists" as a meaningful proposition which can be argued for or against.

Logically a person must belong to one and only one of these 3 mutually exclusive categories:[citation needed]

1. You believe the philosophical view that the truth value of certain claims —particularly metaphysical claims regarding theology, afterlife or the existence of god, gods, deities, or even ultimate reality— can be known.

2. You don't believe the philosophical view that the truth value of certain claims —particularly metaphysical claims regarding theology, afterlife or the existence of god, gods, deities, or even ultimate reality— can be known.

3. You have doubts about the philosophical view that the truth value of certain claims —particularly metaphysical claims regarding theology, afterlife or the existence of god, gods, deities, or even ultimate reality— can be known, though that doesn't necessarily make one officially Agnostic, but rather simply exhibiting agnostic doubt, which does not have to disqualify a belief that one can actually know truth.

As an example a person can be a Presbyterian, and not be absolutely certain that there is a God. This person simply has faith that there is without reason.

Philosophical views

Among the most famous agnostics (in the original sense) have been Thomas Henry Huxley, Robert G. Ingersoll and Bertrand Russell. Pope Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger, also wrote extensively about truth and agnosticism.

It has been suggested that Thomas Henry Huxley and agnosticism and Talk:Agnosticism#Merger proposal be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2008. |

Agnostic views are as old as philosophical skepticism, but the terms agnostic and agnosticism were created by Huxley to sum up his thoughts on contemporary developments of metaphysics about the "unconditioned" (Hamilton) and the "unknowable" (Herbert Spencer). It is important, therefore, to discover Huxley's own views on the matter. Though Huxley began to use the term "agnostic" in 1869, his opinions had taken shape some time before that date. In a letter of September 23, 1860, to Charles Kingsley, Huxley discussed his views extensively:

- I neither affirm nor deny the immortality of man. I see no reason for believing it, but, on the other hand, I have no means of disproving it. I have no a priori objections to the doctrine. No man who has to deal daily and hourly with nature can trouble himself about a priori difficulties. Give me such evidence as would justify me in believing in anything else, and I will believe that. Why should I not? It is not half so wonderful as the conservation of force or the indestructibility of matter...

- It is no use to talk to me of analogies and probabilities. I know what I mean when I say I believe in the law of the inverse squares, and I will not rest my life and my hopes upon weaker convictions...

- That my personality is the surest thing I know may be true. But the attempt to conceive what it is leads me into mere verbal subtleties. I have champed up all that chaff about the ego and the non-ego, noumena and phenomena, and all the rest of it, too often not to know that in attempting even to think of these questions, the human intellect flounders at once out of its depth.

And again, to the same correspondent, May 6, 1863:

- I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel school. Nevertheless I know that I am, in spite of myself, exactly what the Christian would call, and, so far as I can see, is justified in calling, atheist and infidel. I cannot see one shadow or tittle of evidence that the great unknown underlying the phenomenon of the universe stands to us in the relation of a Father [who] loves us and cares for us as Christianity asserts. So with regard to the other great Christian dogmas, immortality of soul and future state of rewards and punishments, what possible objection can I—who am compelled perforce to believe in the immortality of what we call Matter and Force, and in a very unmistakable present state of rewards and punishments for our deeds—have to these doctrines? Give me a scintilla of evidence, and I am ready to jump at them.

Of the origin of the name agnostic to describe this attitude, Huxley gave the following account:[10]

- When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last. The one thing in which most of these good people were agreed was the one thing in which I differed from them. They were quite sure they had attained a certain "gnosis,"–had, more or less successfully, solved the problem of existence; while I was quite sure I had not, and had a pretty strong conviction that the problem was insoluble.

- So I took thought, and invented what I conceived to be the appropriate title of "agnostic." It came into my head as suggestively antithetic to the "gnostic" of Church history, who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant. To my great satisfaction the term took.

Huxley's agnosticism is believed to be a natural consequence of the intellectual and philosophical conditions of the 1860s, when clerical intolerance was trying to suppress scientific discoveries which appeared to clash with a literal reading of the Book of Genesis and other established Jewish and Christian doctrines. Agnosticism should not, however, be confused with natural theology, deism, pantheism, or other science positive forms of theism.

By way of clarification, Huxley states, "In matters of the intellect, follow your reason as far as it will take you, without regard to any other consideration. And negatively: In matters of the intellect, do not pretend that conclusions are certain which are not demonstrated or demonstrable" (Huxley, Agnosticism, 1889). While A. W. Momerie has noted that this is nothing but a definition of honesty, Huxley's usual definition goes beyond mere honesty to insist that these metaphysical issues are fundamentally unknowable.

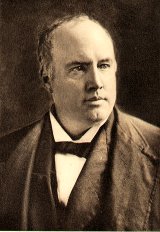

Robert G. Ingersoll, an Illinois lawyer and politician who evolved into a well-known and sought-after orator in 19th century America, has been referred to as the "Great Agnostic."

In an 1896 lecture titled Why I Am An Agnostic, Ingersoll related what led him to believe in agnosticism and articulated that belief with:

- Is there a supernatural power—an arbitrary mind—an enthroned God—a supreme will that sways the tides and currents of the world—to which all causes bow? I do not deny. I do not know—but I do not believe. I believe that the natural is supreme—that from the infinite chain no link can be lost or broken—that there is no supernatural power that can answer prayer—no power that worship can persuade or change—no power that cares for man.

- I believe that with infinite arms Nature embraces the all—that there is no interference—no chance—that behind every event are the necessary and countless causes, and that beyond every event will be and must be the necessary and countless effects.

- Is there a God? I do not know. Is man immortal? I do not know. One thing I do know, and that is, that neither hope, nor fear, belief, nor denial, can change the fact. It is as it is, and it will be as it must be.

In the conclusion of the speech he simply sums up the agnostic belief as:

- We can be as honest as we are ignorant. If we are, when asked what is beyond the horizon of the known, we must say that we do not know.

Bertrand Russell's pamphlet, Why I Am Not a Christian, based on a speech delivered in 1927 and later included in a book of the same title, is considered a classic statement of agnosticism. The essay briefly lays out Russell’s objections to some of the arguments for the existence of God before discussing his moral objections to Christian teachings. He then calls upon his readers to "stand on their own two feet and look fair and square at the world," with a "fearless attitude and a free intelligence."

In 1939, Russell gave a lecture on The existence and nature of God, in which he characterized himself as an agnostic. He said:

- The existence and nature of God is a subject of which I can discuss only half. If one arrives at a negative conclusion concerning the first part of the question, the second part of the question does not arise; and my position, as you may have gathered, is a negative one on this matter.[11]

However, later in the same lecture, discussing modern non-anthropomorphic concepts of God, Russell states:

- That sort of God is, I think, not one that can actually be disproved, as I think the omnipotent and benevolent creator can.[12]

In Russell's 1947 pamphlet, Am I An Atheist Or An Agnostic? (subtitled A Plea For Tolerance In The Face Of New Dogmas), he ruminates on the problem of what to call himself:

- As a philosopher, if I were speaking to a purely philosophic audience I should say that I ought to describe myself as an Agnostic, because I do not think that there is a conclusive argument by which one can prove that there is not a God.

- On the other hand, if I am to convey the right impression to the ordinary man in the street I think I ought to say that I am an Atheist, because when I say that I cannot prove that there is not a God, I ought to add equally that I cannot prove that there are not the Homeric gods.

In his 1953 essay, What Is An Agnostic? Russell states:

- An agnostic thinks it impossible to know the truth in matters such as God and the future life with which Christianity and other religions are concerned. Or, if not impossible, at least impossible at the present time.

However, later in the essay, Russell says:

- I think that if I heard a voice from the sky predicting all that was going to happen to me during the next twenty-four hours, including events that would have seemed highly improbable, and if all these events then produced to happen, I might perhaps be convinced at least of the existence of some superhuman intelligence.

According to Ratzinger, if the question of the knowability of God is not addressed, then “agnosticisim would in fact be the only correct attitude for man,” an “honest and devout” acknowledgement of that which eludes our field of vision. Ratzinger (later elected as Pope Benedict XVI) also cautions against a premature objection to agnosticism, one that is merely based on affirming man's “thirst for the infinite.” He says that the best critique lies in the practical realm.

- The true way to call agnosticism into question is to ask whether its program can be realized. Is it possible for us, as human beings, purely and simply to lay aside the question of our origin, of our final destiny, and of the measure of our existence? Can we be content to live under the hypothetical formula “as if God did not exist” while it is possible that he does in fact exist? (...) I am forced in practice to choose between two alternatives: either to live as if God did not exist or else to live as if God did exist and was the decisive reality of my existence. What is at stake [in agnosticism] is the praxis of one’s life.[13]

Ratzinger thinks that human reason has the power to know reality, and attain the truth. For this, he alludes to the achievements of the natural sciences. He believes that agnosticism is a self-limitation of reason rooted in Kant: reason imposes limits on itself which can lead to dangerous pathologies of religion, such as terrorism and pathologies of science, such as ecological disasters. He thinks that this self-limitation dishonors reason and is contradictory to the modern acclamation of science, whose basis is the power of reason.[14][15]

When agnostics argue that God is unknowable because he cannot be experienced and tested scientifically, Ratzinger differentiates God from other knowable objects:

- This question regards not that which is below us, but that which is above us. It regards, not something we could dominate, but that which exercises its lordship over us and over the whole of reality.[13]

- [To] impose our laboratory conditions upon God...implies that we deny God as God by placing ourselves above him, by discarding the whole dimension of love... [To think thus] would make God our servant.[16]

- There are many things that we do not see but they exist and are essential...We do not see our intelligence and we have it: we do not see our soul and yet it exists and we see its effects, because we can speak, think and make decisions.[17]

Ratzinger thinks that there is a natural knowledge of God "through the things he has made," and agrees with Paul of Tarsus that “agnosticism that is lived out as atheism” is not “an innocent position.”[13][18][need quotation to verify]

- Agnosticism is always the fruit of a refusal of that knowledge which is in fact offered to man… Man is not condemned to remain in uncertainty about God. He can “see” him, if he listens to the voice of God’s Being and to the voice of his creation and lets himself be guided by this. The history of religions is coextensive with the history of humanity. As far as we know, there has never been an epoch in which the question of the One who is totally other, the Divine, has been alien to man. The knowledge of God has always existed.[13]

Notes

- ^ Major Religions Ranked by Size

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary, 2000, under 'agnostic'

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary, 2000, under 'agnostic'

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Additions Series, 1993

- ^ Hume, David, "An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding" (1748)

- ^ "The Nature and Attributes of God," Catholic Encyclopedia, [1]

- ^ Agnosticism, II., Catholic Encyclopedia, New Advent. [2]

- ^ Agnosticism, VIII., Catholic Encyclopedia, New Advent.[3]

- ^ Cline, Austin. "Atheism vs. Agnosticism: What's the Difference? Are they Alternatives to Each Other?". Retrieved 2006-09-24.

- ^ Huxley, Thomas. Collected Essays. pp. 237–239. ISBN 1-85506-922-9.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand. Collected Papers, Vol 10. p. 255.

- ^ Collected Papers, Vol. 10, p.258

- ^ a b c d Ratzinger, Joseph (2006). Christianity and the Crisis of Cultures. Ignatius Press. ISBN 9781586171421.

- ^ Ratzinger, Joseph (2004). Truth and Tolerance: Christian Belief And World Religions. Ignatius Press.

- ^ Benedict XVI, Address at the University of Regensburg 2006

- ^ Ratzinger, Joseph (2007). Jesus of Nazareth. Random House.

- ^ Benedict XVI, Catechetical meeting, October 2005 This is Ratzinger's reply to a child about how Jesus can be in the Eucharist.

- ^ Cf. Romans 1:18-21

References

- Man's Place In Nature, Thomas Huxley, ISBN 0-375-75847-X

- Why I Am Not a Christian, Bertrand Russell, ISBN 0-671-20323-1

- Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, David Hume, ISBN 0-14-044536-6

- Language, Truth, and Logic, A.J. Ayer, ISBN 0-486-20010-8

- Atheism, the Case Against God, George H. Smith, ISBN 0-87975-124-X

- CIA estimate of religious affiliation by country uses "other", "none", or "unspecified" as descriptive terms

See also

- Agnostic theism

- Asimov's Guide to the Bible

- Existentialism

- Gnosticism

- Ietsism

- James I of England

- Jefferson Bible

- List of agnostics

- Nihilism

- Rationalist movement

- Relativism

- Religiosity

- Religious skepticism

- Russell's teapot

- Secularism

- Skepticism

- Solipsism

- The Skeptic's Annotated Bible

- Thomas Henry Huxley and agnosticism

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Agnostic Discussion Forums: Gathering place for agnostics to share views.

- What Is An Agnostic? by Bertrand Russell, [1953].

- Why I am Not a Christian by Bertrand Russell (March 6, 1927).

- Why I Am An Agnostic by Robert G. Ingersoll, [1896].

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Agnosticism

- The Internet Infidels Discussion Forums(Worldwide)

- The Secular Web

- Apathetic Agnostics

- Some reflections and quotes about agnosticism

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Agnosticism - from ReligiousTolerance.org

- Agnosticismo Spanish/Español with videos.

- Agnostic Universe

- What do Agnostics Believe? - A Jewish perspective

- agnosticism Robert Todd Carroll, Skeptic's Dictionary

- Fides et Ratio – the relationship between faith and reason Karol Wojtyla [1998]

- A critical examination of the agnostic Buddhism of Stephen Batchelor

- Catholic Encyclopedia on agnosticism