Slug: Difference between revisions

Bella Swan (talk | contribs) Undid revision 210010393 by 65.33.208.77 (talk) |

Supersquid (talk | contribs) m reverting to remove missed vandalism |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

==Subinfraorders, superfamilies, and families== |

|||

No pictures available. |

|||

*Subinfraorder [[Orthurethra]] |

|||

**Superfamily [[Achatinelloidea]] <small>Gulick, 1873</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Cochlicopoidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1900</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Partuloidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1900</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Pupilloidea]] <small>Turton, 1831</small> |

|||

*Subinfraorder [[Sigmurethra]] |

|||

**Superfamily [[Acavoidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1895</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Achatinoidea]] <small>Swainson, 1840</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Aillyoidea]] <small>Baker, 1960</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Arionoidea]] <small>[[John Edward Gray|J.E. Gray]] in Turnton, 1840</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Athoracophoroidea]] |

|||

***Family [[Athoracophoridae]] |

|||

**Superfamily [[Buliminoidea]] <small>Clessin, 1879</small> |

|||

***Family [[Bulimulidae]] |

|||

**Superfamily [[Camaenoidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1895</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Clausilioidea]] <small>Mörch, 1864</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Dyakioidea]] <small>Gude & Woodward, 1921</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Gastrodontoidea]] <small>Tryon, 1866</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Helicoidea]] <small>[[Constantine Samuel Rafinesque|Rafinesque]], 1815</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Helixarionoidea]] <small>Bourguignat, 1877</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Limacoidea]] <small>[[Constantine Samuel Rafinesque|Rafinesque]], 1815</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Oleacinoidea]] <small>H. & A. Adams, 1855</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Orthalicoidea]] <small>Albers-Martens, 1860</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Plectopylidoidea]] <small>Moellendorf, 1900</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Polygyroidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1894</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Punctoidea]] <small>Morse, 1864</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Rhytidoidea]] <small>Pilsbry, 1893</small> |

|||

***Family [[Rhytididae]] |

|||

**Superfamily [[Sagdidoidera]] <small>Pilsbry, 1895</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Staffordioidea]] <small>[[Johannes Thiele|Thiele]], 1931</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Streptaxoidea]] <small>[[John Edward Gray|J.E. Gray]], 1806</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Strophocheiloidea]] <small>[[Johannes Thiele|Thiele]], 1926</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Trigonochlamydoidea]] <small>Hese, 1882</small> |

|||

**Superfamily [[Zonitoidea]] <small>Mörch, 1864</small> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 01:48, 4 May 2008

Slug is a common non-scientific word which is most often applied to any gastropod mollusk whatsoever that has a very reduced shell, a small internal shell, or no shell at all. A slug-like body is an adaptation which has occurred many times in various groups of snails.

The common name "slug" is most often applied to land species, but the word has also been applied to many marine species. The largest group of marine shell-less gastropods or sea slugs are the nudibranchs, but there are in addition many other groups of sea slug such as the heterobranch sea butterflies, sea angels, and sea hares, as well as the only very distantly related, pelagic, caenogastropod sea slugs, which are within the superfamily Carinarioidea.

Evolutionarily speaking, the loss or reduction of the shell in gastropods is a derived characteristic; the same basic body design has independently evolved several times, making slugs a strikingly polyphyletic group. In other words, the shell-less condition has arisen many times in the evolutionary past, and because of this, the various different taxonomic families of slugs are often not at all closely related to one another, despite a superficial similarity.

This article is primarily about pulmonate land slugs.

Land slugs

Although land slugs have undergone torsion (180º twisting of the internal organs) during development, their bodies are streamlined and worm-like, and so externally they show only a little external evidence of this asymmetry, and that mainly in the positioning of the pneumostome.[citation needed]

The soft, slimy bodies of slugs are prone to desiccation, so land-living slugs are confined to moist environments.

Morphology and behaviour

Slugs macerate food using their radula, a rough, tongue-like organ with many tiny tooth-like denticles.

Like snails, most slugs have two pairs of 'feelers' or tentacles on their head; the upper pair being light sensors, while the lower pair provides the sense of smell. Both pairs are retractable and can be regrown if lost. On top of the slug, behind the head, is the saddle-shaped mantle, and under this are the genital opening and anus. The mantle also has a hole, the pneumostome, for respiration. The slug moves by rhythmic muscular action of its foot.

Some species hibernate underground during the winter in temperate climates, but in other species, the adults die in the autumn.

Mucus

Slugs' bodies are made up mostly of water and are prone to desiccation. They must generate protective mucus to survive. In drought conditions they hide under fallen logs, rocks, plants, and planters in order to help retain body moisture.

Slugs produce two types of mucus: one which is thin and watery, and another which is thick and sticky. Both are hygroscopic. The thin mucus is spread out from the centre of the foot to the edges. The thick mucus spreads out from front to back.

Mucus is very important to slugs because it helps them move around, and contains fibres which prevent the slug from sliding down vertical surfaces. Mucus also provides protection against predators and helps retain moisture. Some species use slime cords to lower themselves on to the ground, or to suspend a pair of slugs during copulation.

Reproduction

Slugs are hermaphrodites, having both female and male reproductive organs. Once a slug has located a mate they encircle each other and sperm is exchanged through their protruding genitalia. A few days later around 30 eggs are laid into a hole in the ground or under the cover of objects such as fallen logs.

A commonly seen practice among many slugs is apophallation, when one or both of the slugs chews off the other's penis. The penis of these species is curled like a cork-screw and often becomes entangled in their mate's genitalia in the process of exchanging sperm. When all else fails, apophallation allows the slugs to separate themselves. Once its penis has been removed, a slug is still able to participate in mating subsequently, but only using the female parts of its reproductive system.

Ecology

Many species of slugs play an important role in ecology by eating dead leaves, fungus, and decaying vegetable material. Some slugs are predators. Most slugs will also eat carrion including dead of their own kind.

Predators

Frogs, toads, snakes, hedgehogs, eastern box turtles, and also some birds and beetles are natural slug predators. Slugs, when attacked, can contract their body, making themselves harder and more compact and thus more difficult for many animals to grasp. The unpleasant taste of the mucus is also a deterrent.

Human relevance

A small number of species of slugs feed on fruits and vegetables prior to harvest, making holes in the crop that makes it more vulnerable to rot and disease, and making individual items unsuitable to sell. Slugs such as Deroceras reticulatum are a serious pest to agriculture.

In a few cases, humans have contracted parasite-induced meningitis from eating raw slugs [1].

The banana slug, Ariolimax dolichophallus, is the mascot of the University of California at Santa Cruz.

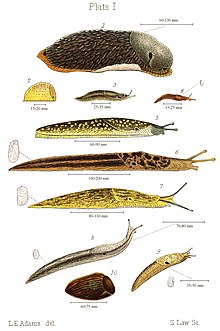

Photographs

-

Red slug, Arion rufus - red color form on a rhubarb leaf, in England

-

Banana slug, Ariolimax columbianus, Univ. of Calif. Santa Cruz

-

Great grey slug, Limax maximus, in Illinois, USA

-

Two Great grey slugs mating

-

Tropical leatherleaf, Laevicaulis alte

-

A slug from North Bend, Washington, USA

-

A slug from the Western Ghats of India

-

Close up of mating Great Grey Slug found in Maryland, USA

-

Mating Great Grey Slug found in Maryland, USA

-

Great Grey Slug pictured in Maryland, USA

Subinfraorders, superfamilies, and families

- Subinfraorder Orthurethra

- Superfamily Achatinelloidea Gulick, 1873

- Superfamily Cochlicopoidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Partuloidea Pilsbry, 1900

- Superfamily Pupilloidea Turton, 1831

- Subinfraorder Sigmurethra

- Superfamily Acavoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Achatinoidea Swainson, 1840

- Superfamily Aillyoidea Baker, 1960

- Superfamily Arionoidea J.E. Gray in Turnton, 1840

- Superfamily Athoracophoroidea

- Family Athoracophoridae

- Superfamily Buliminoidea Clessin, 1879

- Family Bulimulidae

- Superfamily Camaenoidea Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Clausilioidea Mörch, 1864

- Superfamily Dyakioidea Gude & Woodward, 1921

- Superfamily Gastrodontoidea Tryon, 1866

- Superfamily Helicoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Helixarionoidea Bourguignat, 1877

- Superfamily Limacoidea Rafinesque, 1815

- Superfamily Oleacinoidea H. & A. Adams, 1855

- Superfamily Orthalicoidea Albers-Martens, 1860

- Superfamily Plectopylidoidea Moellendorf, 1900

- Superfamily Polygyroidea Pilsbry, 1894

- Superfamily Punctoidea Morse, 1864

- Superfamily Rhytidoidea Pilsbry, 1893

- Family Rhytididae

- Superfamily Sagdidoidera Pilsbry, 1895

- Superfamily Staffordioidea Thiele, 1931

- Superfamily Streptaxoidea J.E. Gray, 1806

- Superfamily Strophocheiloidea Thiele, 1926

- Superfamily Trigonochlamydoidea Hese, 1882

- Superfamily Zonitoidea Mörch, 1864

References

- ^ "Health and Medicals News - Man's brain infected by eating slugs". Retrieved 2006-03-15.

External links

- Pancake Slug (Veronicella sloanei) Info

- Land Slugs and Snails and Their Control (pub. 1959) hosted by the UNT Government Documents Department