Virginia: Difference between revisions

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

===Ethnicity=== |

===Ethnicity=== |

||

The five largest reported [[ancestry]] groups in Virginia are: [[African]] (19.6%), [[German-American|German]] (11.7%), unspecified [[American ancestry|American]] (11.4%), [[English American|English]] (11.1%), and [[Irish American|Irish]] (9.8%), which includes Scots-Irish.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=04000US51&-qr_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U_QTP13&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U |title= Virginia - QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000 |date= 2000 |work= [[United States Census Bureau]] |accessdate= 2007-12-05}}</ref> 20.8% of Virginians are African-American, most of whom are descendants of enslaved Africans who worked its [[tobacco]], [[cotton]], and [[hemp]] plantations. Initially, they were imported from west central Africa, primarily [[Angola]]. During the eighteenth century, however, half were derived from various ethnicities located in the [[Niger Delta]] region of modern day [[Nigeria]].<ref>{{cite book |first= Gwendolyn Midlo |last= Hall |title= Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links |location= Chapel Hill |publisher= University of North Carolina Press |year= 2005}}</ref> The twentieth century [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]] of blacks from the rural South to the North reduced Virginia's black population; however, in the past forty years there has been a reverse migration of blacks [[New Great Migration|returning]] to Virginia and the rest of the South.<ref name=demographics>{{cite web |url= http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=04000US51&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_DP5&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=en&-_sse=on |title= Virginia - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006 |work= [[United States Census Bureau]] |date= 2006 |accessdate= 2007-12-05}}</ref> |

The five largest reported [[ancestry]] groups in Virginia are: [[African]] (19.6%), [[German-American|German]] (11.7%), unspecified [[American ancestry|American]] (11.4%), [[English American|English]] (11.1%), and [[Irish American|Irish]] (9.8%), which includes Scots-Irish.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/QTTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=04000US51&-qr_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U_QTP13&-ds_name=DEC_2000_SF3_U |title= Virginia - QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000 |date= 2000 |work= [[United States Census Bureau]] |accessdate= 2007-12-05}}</ref> 20.8% of Virginians are African-American, most of whom are descendants of enslaved Africans who worked its [[tobacco]], [[cotton]], and [[hemp]] plantations. Initially, they were imported from west central Africa, primarily [[Angola]]. During the eighteenth century, however, half were derived from various ethnicities located in the [[Niger Delta]] region of modern day [[Nigeria]].<ref>{{cite book |first= Gwendolyn Midlo |last= Hall |title= Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links |location= Chapel Hill |publisher= University of North Carolina Press |year= 2005}}</ref> The twentieth century [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]] of blacks from the rural South to the North reduced Virginia's black population; however, in the past forty years there has been a reverse migration of blacks [[New Great Migration|returning]] to Virginia and the rest of the South.<ref name=demographics>{{cite web |url= http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=04000US51&-qr_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_DP5&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=en&-_sse=on |title= Virginia - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006 |work= [[United States Census Bureau]] |date= 2006 |accessdate= 2007-12-05}}</ref> Virginia also continues to be the home to eight federally recognized and organized American Indian tribes. Six other incorporated groups are officially recognized as Indian tribes by the Commonwealth of Virginia. <ref> name=demographics>{{cite web |url=http://virginiaindians.pwnet.org/index.php |title= Virginia's First People}}</ref> |

||

The western mountains have many settlements founded by [[Scots-Irish]] immigrants before the Revolution. <ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.virginia.org/site/features.asp?featureid=225 |title= Scots-Irish Sites in Virginia |work= [http://www.virginia.org/ Virginia Is For Lovers] |date= [[January 3]], [[2008]] |accessdate= 2008-02-02}}</ref> There are also sizable numbers of people of German descent in the northwestern mountains and Shenandoah Valley. People of English heritage settled throughout the state during the colonial period, and others of British heritage have migrated there through the decades for work.<ref name=dutch/> Because of more recent immigration in the late 20th century and early 21st century, there are rapidly growing populations of Hispanics, particularly [[Central America]]ns, and Asians in [[Northern Virginia]]. The Hispanic population of the state tripled from 1990 to 2006, with two-thirds of Hispanics living in Northern Virginia.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://hamptonroads.com/2008/02/states-hispanic-population-nearly-triples-1990-0 |title= State's Hispanic population nearly triples since 1990 |work= [[University of Virginia]] |date= February, 2008 |accessdate= 2008-02-08}}</ref> As of 2007, 6.6% of Virginians are [[Hispanic]], 5.5% are [[Asian people|Asian]], and 1% are American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.<ref name=demographics/> Northern Virginia has the largest [[Vietnamese American|Vietnamese]] population on the East Coast, with slightly more than {{nowrap|99,000 Vietnamese}} residents, whose major wave of immigration followed the [[Vietnam War]].<ref>{{cite journal |title= Vietnamese American Place Making in Northern Virginia |first= Joseph |last= Wood |journal= Geographical Review |volume= 87 |issue= 1 |month= January |year= 1997 |pages= 58–72 |url= http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0016-7428%28199701%2987%3A1%3C58%3AVAPMIN%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 |accessdate= 2007-11-29}}</ref> |

The western mountains have many settlements founded by [[Scots-Irish]] immigrants before the Revolution. <ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.virginia.org/site/features.asp?featureid=225 |title= Scots-Irish Sites in Virginia |work= [http://www.virginia.org/ Virginia Is For Lovers] |date= [[January 3]], [[2008]] |accessdate= 2008-02-02}}</ref> There are also sizable numbers of people of German descent in the northwestern mountains and Shenandoah Valley. People of English heritage settled throughout the state during the colonial period, and others of British heritage have migrated there through the decades for work.<ref name=dutch/> Because of more recent immigration in the late 20th century and early 21st century, there are rapidly growing populations of Hispanics, particularly [[Central America]]ns, and Asians in [[Northern Virginia]]. The Hispanic population of the state tripled from 1990 to 2006, with two-thirds of Hispanics living in Northern Virginia.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://hamptonroads.com/2008/02/states-hispanic-population-nearly-triples-1990-0 |title= State's Hispanic population nearly triples since 1990 |work= [[University of Virginia]] |date= February, 2008 |accessdate= 2008-02-08}}</ref> As of 2007, 6.6% of Virginians are [[Hispanic]], 5.5% are [[Asian people|Asian]], and 1.8% are American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.<ref name=demographics/> Northern Virginia has the largest [[Vietnamese American|Vietnamese]] population on the East Coast, with slightly more than {{nowrap|99,000 Vietnamese}} residents, whose major wave of immigration followed the [[Vietnam War]].<ref>{{cite journal |title= Vietnamese American Place Making in Northern Virginia |first= Joseph |last= Wood |journal= Geographical Review |volume= 87 |issue= 1 |month= January |year= 1997 |pages= 58–72 |url= http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0016-7428%28199701%2987%3A1%3C58%3AVAPMIN%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2 |accessdate= 2007-11-29}}</ref> |

||

{|border="0" align=center |

{|border="0" align=center |

||

Revision as of 23:05, 22 May 2008

Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Admitted to the Union | June 25, 1788 (10th) |

| Capital | Richmond |

| Largest city | Virginia Beach |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Northern Virginia |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Timothy M. Kaine (D) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Bill Bolling (R) |

| • Upper house | {{{Upperhouse}}} |

| • Lower house | {{{Lowerhouse}}} |

| U.S. senators | John Warner (R) Jim Webb (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 8 Rep. and 3 Dem. (list) |

| Population | |

• Total | 7,078,515 |

| • Density | 178.8/sq mi (69.03/km2) |

| • Median household income | $53,275 |

| • Income rank | 10th |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | English 94.3%, Spanish 5.8% |

| Latitude | 36° 32′ N to 39° 28′ N |

| Longitude | 75° 15′ W to 83° 41′ W |

The Commonwealth of Virginia (Template:PronEng) is an American state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is the 12th-most populous state in the U.S. with over 7.7 million residents, and the 35th-largest in area.[2] It is named after Queen Elizabeth I of England, who, never having married, was known as the 'Virgin Queen'. The state is also known as the "The Old Dominion" as King Charles II of England gave it the position of 'royal dominion' along with England, Scotland, and Ireland, and was the oldest of his settlements in America. It is sometimes known as the "Mother of Presidents", because it is the birthplace of the most U.S. presidents, and occasionally as the 'Mother of States and Statesmen' due to the number of states originating from its territory and the number of statesmen having been born in Virginia.[3][4]

The roots of modern Virginia trace back to the founding of the Virginia Colony in 1607 by the Virginia Company of London. Agriculture, colonialism and slavery played significant roles in Virginia's early economy and politics. It was the first permanent New World English colony and became one of the thirteen colonies that would take part in the American Revolution, and subsequently became the heart of the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

The capital of the commonwealth is Richmond, while Virginia Beach is the most populous city, and Fairfax County is the most populous political subdivision. Although traditionally conservative and historically part of the Southern United States, modern Virginia is a politically competitive state for both major national political parties.[5] Virginia's government is ranked with the highest efficiency grade in the nation.[6]

Virginia has an economy with several important industries, including the federal government administration in Northern Virginia and military-industrial bases in Hampton Roads, as well as significant agricultural production. The Historic Triangle includes Jamestown, Yorktown and the living museum of Colonial Williamsburg as popular tourist destinations.[7] The growth of the technology sector has made computer chips the state's leading export, with the industry based on the strength of Virginia's public schools and universities, some of which are at the top of national rankings.[8]

Geography

Virginia has an area of 42,774 square miles (110,784 km2) making it the thirty-fifth largest state.[9] Virginia is bordered by Maryland and the District of Columbia to the north and east; the Atlantic Ocean to the east; by North Carolina and Tennessee to the south; by Kentucky to the west and by West Virginia to the north and west. Due to a peculiarity of Virginia's original charter, its boundary with Maryland does not extend past the low-water mark of the southern shore of the Potomac River, meaning Maryland and the District of Columbia contain the whole width of the river rather than splitting it between them and Virginia.[10]

Geology and terrain

The Chesapeake Bay divides the terresterially contiguous portion of the Commonwealth with a two county peninsula- Virginia's Eastern Shore. Many of Virginia's rivers flow into the Chesapeake.[11] The Virginia seismic zone has not had a history of regular activity. Earthquakes are rarely above 4.5 on the Richter magnitude scale because Virginia is located centrally on the North American Plate. The largest earthquake, at 5.9 magnitude, came in 1897 in Blacksburg.[12] Besides coal, resources such as slate, kyanite, and sand and gravel are mined with an annual value over $2 billion.[13] Geographically and geologically, Virginia is divided into five regions from east to west:

- Tidewater—Coastal plain between the Atlantic coast and the fall line, including the Eastern Shore and major estuaries.

- Piedmont—Mesozoic sedimentary and igneous rock based foothills east of the Appalachian Mountains, but including the Southwest Mountains.[14]

- Blue Ridge Mountains—includes Mount Rogers and the Appalachian Trail.

- Ridge and Valley—includes Massanutten Mountain and the Great Appalachian Valley with carbonate rock below.

- Appalachian Plateau—west of the mountains toward the Allegheny Plateau with a dendritic drainage system flowing into the Ohio River basin.[15]

Climate

Most of the state east of the Blue Ridge Mountains, plus the southern part of the Shenandoah Valley, has a humid subtropical climate. In the mountainous areas west of the Blue Ridge, the climate becomes humid continental.[16] The moderating influence of the ocean from the east, powered by the Gulf Stream, also creates the potential for hurricanes near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, making the coastal area vulnerable. Although Hurricane Gaston in 2004 inundated Richmond hurricanes rarely threaten far inland.[17]

Thunderstorms are an occasional concern, with the state averaging from 35-45 days of thunderstorm activity annually. The area of most frequent occurrence is in the west.[18] The state averages in just in excess of 85 tornadoes per year, though most are F2 and lower on the Fujita scale.[19] Cold air masses arriving over the mountains, especially in winter, can lead to significant snowfalls in those regions, such as the Blizzard of 1996. The interaction of these elements with the state's topography creates micro-climates in the Shenandoah Valley, the mountainous southwest, and the coastal plains that are distinct.[20] In recent years the expansion of the southern suburbs of Washington into Northern Virginia, has created an urban heat island due to the increased energy output of more densely used areas.[21] In 2005, seventeen of the ninety-five counties received failing grades for air quality, with Fairfax County having the worst in the state.[22]

Flora and fauna

Virginia is sixty-five percent covered by forests.[23] In some mountainous areas of the state, pine predominates and there is also the occasional naturally growing prickly pear cactus. Lower altitudes are more likely to have small but dense stands of moisture-loving hemlocks and mosses in abundance. Other commonly found plants include oak, hickory, chestnut, maple, tulip poplar, mountain laurel, milkweed, daisies, and many species of ferns. Gypsy moth infestations beginning in the early 1990s have eroded the dominance of the oak forests.[24]

Mammals include Whitetailed deer, black bear, bobcat, raccoon, skunk, opossum, groundhog, gray fox, and eastern cottontail rabbit.[25] Though unsubstantiated, there have been some reported sightings of mountain lion in areas of the state.[26] Birds include Virginia cardinal, barred owls, Carolina chickadees, Red-tailed Hawks, and wild turkeys. The Peregrine Falcon was reintroduced into Shenandoah National Park in the mid-1990s.[27] Freshwater fish include brook trout, longnose and blacknose dance, and the bluehead chub.[28] The Chesapeake Bay is home to many species, including blue crabs, clams, oysters, and rockfish, also known as striped bass.[29]

Virginia has many National Park Service units, including one national park, the Shenandoah National Park. Shenandoah was established in 1935 and encompasses the scenic Skyline Drive. Almost forty percent of the park's area (79,579 acres/322 km²) has been designated as Wilderness and is protected as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. Other parks in Virginia, such as Great Falls Park and Prince William Forest Park are included in the many areas in the National Park System. Additionally, there are thirty-four Virginia state parks, run by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation and the Virginia Department of Forestry.[30] The Chesapeake Bay, while not a national park, is protected by both state and federal legislation, and the jointly run Chesapeake Bay Program which conducts restoration on the bay and its watershed. The Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge is protected by both Virginia and North Carolina.

History

Jamestown 2007 marked Virginia's quadricentennial year, celebrating four hundred years since the establishment of the Jamestown Colony. Over the centuries Virginia has been at the front of warfare from the American Revolution and the Civil War to the Cold War and the War on Terrorism. The far-reaching social changes of the mid- to late-20th century were expressed by broad-based celebrations marking contributions of three cultures to the state: Native American, European and African.[31]

Colony

At the time of the English colonization of Virginia, Native American people were living in what now is Virginia. Native American tribes in Virginia included the Cherokee, Chesepian, Chickahominy, Mattaponi, Meherrin, Monacan, Nansemond, Nottoway, Pamunkey, Powhatan, Rappahannock, Saponi and others.[32] The natives are often divided into three groups, based to a large extent upon language differences. The largest group are known as the Algonquian led by Chief Powhatan. It is estimated that at the time of English contact in the Tidewater region, the native Tidewater population of the Powhatan numbered 20,000. Powhatan controlled more than 32 chiefdoms in more than 150 town and settlements of various sizes. Two groups distinct from the Powhatan, the Nottoway and Meherrin, who numbered about 20,000 also, and lived in the Coastal Plain of Virginia beside other, more numerous Powhatan villages. They spoke dialects of the Iroquoian language and lived along the Nottoway and Meherrin Rivers. Like the coastal Algonquian (Powhatan), the people farmed and hunted, and their houses were similarly interspersed among fields of crops. Unlike members of the Powhatan chiefdom, however, the Nottoway and Meherrin lived as tribes in autonomous villages, with a local chief holding little sway beyond the village. A number of Indian tribes that spoke dialects of the Siouan language lived in the Piedmont of Virginia.[33]

In 1583, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Sir Walter Raleigh a charter to explore and plant a colony north of Florida.[34] In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh explored the Atlantic coast of North America. Raleigh, or possibly the Queen herself, named the area "Virginia" after Queen Elizabeth, known as the "Virgin Queen" because she never married.[35] The name eventually applied to the whole coast from South Carolina to Maine, and included Bermuda. The London Virginia Company was incorporated as a joint stock company by the proprietary Charter of 1606, which granted land rights to this area.[36] The Company financed the first permanent English settlement in the New World. Jamestown, named for King James I, was founded on May 13, 1607 by Captains Christopher Newport and John Smith.[37] In 1609 many colonists died during the "starving time" after the loss of the Third Supply's flagship, the Sea Venture.[38]

The House of Burgesses was established in 1619 as the colony's elected governance.[39] During this early period Virginia's population grew with the introduction of settlers and servants into the burgeoning plantation economy. In 1619, African servants were first introduced, with slavery being codified in 1661.[40] After 1618 the headright system led to more indentured servants from Europe.[41] In this system, settlers received land for each servant they transported.[42] Land from the Native Americans was appropriated by force and treaty, including the Treaty of 1677, which made the signatory tribes tributary states.[43] The colonial capital was moved in 1698 to Williamsburg, where the College of William and Mary had been founded in 1693.[44]

The House of Burgesses was temporarily dissolved in 1769 by the Royal governor Lord Botetourt, after Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee led speeches on the distresses of the British taxation without representation. In 1773, Henry and Lee formed a committee of correspondence, and in 1774 Virginia sent delegates to the Continental Congress.[45] On May 15, 1776, the Virginia Convention declared independence from the British Empire.[46] Shortly after, the Virginia Convention adopted the Virginia Declaration of Rights written by George Mason, a document that influenced the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights.[47] Then on June 29, 1776, the convention enacted a constitution, drafted by Thomas Jefferson, that formally declared Virginia as an independent commonwealth.[48]

During the American Revolutionary War, the capital was moved to Richmond at the urging of Governor Thomas Jefferson, fearing Williamsburg's location made it vulnerable to British attack.[49] In 1781, the combined action of Continental and French land and naval forces trapped the British on the Yorktown peninsula, where troops under George Washington and French Comte de Rochambeau defeated British General Cornwallis in the Battle of Yorktown. The British surrender on October 19, 1781 so shifted British public opinion that it led to the end of major hostilities and secured the independence of the colonies.[50]

Statehood

Virginians were instrumental in writing the United States Constitution. James Madison drafted the Virginia Plan in 1787 and the Bill of Rights in 1789. Virginia ratified the Constitution on June 25, 1788. The three-fifths compromise ensured that Virginia initially had the largest bloc in the House of Representatives, which with the Virginia dynasty of presidents gave the commonwealth national importance. In 1790, both Virginia and Maryland ceded territory to form the new District of Columbia, though in 1847 the Virginian area was retroceded.[38] Virginia is sometimes called "Mother of States" because of its role in being carved into several mid-western states.[51]

Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831 and John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859 showed deep social discontent over the issue of slavery in Virginia and its role in the plantation economy. Besides agriculture, slave labor was also increasingly used in mining, shipbuilding and other industries.[52] By 1860, almost half a million people, roughly thirty-one percent of the total population of Virginia, were enslaved.[53]

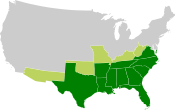

Virginia seceded from the Union on April 17, 1861 after Abraham Lincoln called for a response to the Confederate States of America (CSA) attack on Fort Sumter. Virginia turned over its military and ratified the CSA constitution in June 1861. The CSA then moved its capitol to Richmond. In 1863 forty-eight counties in the northwest of the state separated from Virginia to form the State of West Virginia. Virginia in the American Civil War saw more battles fought than anywhere else, including the Battles of Bull Run, the Seven Days Battles, the Battle of Chancellorsville, and the concluding Battle of Appomattox Courthouse. After the capture of Richmond, the Confederate capitol was moved to Danville, Virginia. With the work of the Committee of Nine during post-war Reconstruction, Virginia formally rejoined the Union on January 26, 1870, and adopted a constitution which provided for Negro suffrage, a system of free public schools, and guarantee of civil and political rights.[54]

However during the culmination of the Jim Crow era, legislators rewrote the Constitution of Virginia to include a poll tax and other measures on voter registration that effectively disfranchised African Americans, leading to underfunding for segregated schools and services, and the lack of representation.[55] From 1900 to 1904, estimated black voting in Presidential elections dropped to zero.[56] African Americans still created vibrant communities and made progress. The first black students attended the University of Virginia School of Law in 1950, and Virginia Tech in 1953.[57] Despite the determination of Brown v. Board of Education, Virginia declared in 1958 that desegregated schools would not receive state funding, under the policy of "massive resistance" spearheaded by the powerful segregationist Senator Harry F. Byrd.[58] In 1959 Prince Edward County closed their schools rather than integrate them.[59]

The subsequent lawsuit to open the schools, Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, was won by Richmond natives Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, beginning the slow integration of Virginia's schools.[58] In addition, the Civil Rights Movement gained many participants in the 1960s and achieved the moral force to gain national legislation for protection of suffrage and civil rights for African Americans. In 1971, state legislators rewrote the constitution, after goals such as legal integration and the repeal of Jim Crow laws had been achieved. On January 13, 1990, Douglas Wilder was elected Governor of Virginia and became the first African American to achieve that office since Reconstruction.

In 1926, Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, rector of Williamsburg's Bruton Parish Church, began restoration of colonial era buildings in the historic district with financial backing of John D. Rockefeller Jr. resulting in Colonial Williamsburg.[7] World War II and the Cold War led to massive expansion of government programs in the areas near Washington. Northern Virginia was targeted in the September 11, 2001 attacks because of the Pentagon site, where one hundred eighty-five people died.

Cities and towns

Virginia is divided into independent cities and counties, which function in the same manner. According to the US Census Bureau, independent cities are considered county-equivalent.[60] As of 2006, thirty-nine of the forty-two independent cities in the United States are in Virginia. Incorporated towns are recognized as part of the 95 counties in Virginia, but are not independent. There are also hundreds of other unincorporated communities in Virginia. Virginia does not have any further political subdivisions, such as villages or townships.

Virginia has eleven Metropolitan Statistical Areas. Northern Virginia, Hampton Roads, and Richmond-Petersburg are the three most populated metropolitan areas of the state. Richmond is the capital of Virginia, and the Richmond metropolitan area has a population of over 1.2 million people.[61] Virginia Beach is the most populous city in the commonwealth, with Norfolk and Chesapeake second and third, respectively. Norfolk forms the urban core of this metropolitan area, which is home to over 1.7 million people and the world's largest naval base.[62]

Although it is not incorporated as a city, Fairfax County is the most populous locality in Virginia, with over one million residents.[63] Fairfax has a major urban business and shopping center in Tysons Corner, Virginia's largest office market.[64] Neighboring Loudoun County, with the county seat at Leesburg, is the fastest-growing county in the United States.[65] Arlington County, the smallest self-governing county in the United States by land area, is an urban community organized as a county.[66] Roanoke, with a population of 292,983, is the largest Metropolitan Statistical Area in western Virginia.[67][68] Suffolk, which includes a portion of the Great Dismal Swamp, is the largest city geographically.[69]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 691,737 | — | |

| 1800 | 807,557 | 16.7% | |

| 1810 | 877,683 | 8.7% | |

| 1820 | 938,261 | 6.9% | |

| 1830 | 1,044,054 | 11.3% | |

| 1840 | 1,025,227 | −1.8% | |

| 1850 | 1,119,348 | 9.2% | |

| 1860 | 1,219,630 | 9.0% | |

| 1870 | 1,225,163 | 0.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,512,565 | 23.5% | |

| 1890 | 1,655,980 | 9.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,854,184 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,061,612 | 11.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,309,187 | 12.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,421,851 | 4.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,677,773 | 10.6% | |

| 1950 | 3,318,680 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,966,949 | 19.5% | |

| 1970 | 4,648,494 | 17.2% | |

| 1980 | 5,346,818 | 15.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,187,358 | 15.7% | |

| 2000 | 7,078,515 | 14.4% |

As of 2006, Virginia had an estimated population of 7,642,884, which is an increase of 78,557, or one percent, from the prior year and an increase of 563,854, or eight percent, since the year 2000. This includes an increase from net migration of 276,292 people into the commonwealth. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 151,748 people, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 124,544 people.[70] The center of population of Virginia is located in Goochland County.[71]

English was passed as the commonwealth's official language by statutes in 1981 and 1996, and by law in 2006, though the status is not mandated by the Constitution of Virginia.[72] English is the only language spoken by 6,201,784 (86.9%) Virginians, though it is spoken very well by an additional 536,508 (7.5%) (for a total of 94.3% of the Commonwealth which speaks English.) Spanish has the most speakers of other languages, with 412,416 (5.8%). 240,332 (3.4%) speak Asian and Pacific Islander languages, including Vietnamese and Filipino.[73]

Ethnicity

The five largest reported ancestry groups in Virginia are: African (19.6%), German (11.7%), unspecified American (11.4%), English (11.1%), and Irish (9.8%), which includes Scots-Irish.[74] 20.8% of Virginians are African-American, most of whom are descendants of enslaved Africans who worked its tobacco, cotton, and hemp plantations. Initially, they were imported from west central Africa, primarily Angola. During the eighteenth century, however, half were derived from various ethnicities located in the Niger Delta region of modern day Nigeria.[75] The twentieth century Great Migration of blacks from the rural South to the North reduced Virginia's black population; however, in the past forty years there has been a reverse migration of blacks returning to Virginia and the rest of the South.[70] Virginia also continues to be the home to eight federally recognized and organized American Indian tribes. Six other incorporated groups are officially recognized as Indian tribes by the Commonwealth of Virginia. [76]

The western mountains have many settlements founded by Scots-Irish immigrants before the Revolution. [77] There are also sizable numbers of people of German descent in the northwestern mountains and Shenandoah Valley. People of English heritage settled throughout the state during the colonial period, and others of British heritage have migrated there through the decades for work.[78] Because of more recent immigration in the late 20th century and early 21st century, there are rapidly growing populations of Hispanics, particularly Central Americans, and Asians in Northern Virginia. The Hispanic population of the state tripled from 1990 to 2006, with two-thirds of Hispanics living in Northern Virginia.[79] As of 2007, 6.6% of Virginians are Hispanic, 5.5% are Asian, and 1.8% are American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander.[70] Northern Virginia has the largest Vietnamese population on the East Coast, with slightly more than 99,000 Vietnamese residents, whose major wave of immigration followed the Vietnam War.[80]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Religion

| Religious affiliation[81] | |||||

| Christian: | 76% | Baptist: | 30% | ||

| Protestant: | 49% | Methodist: | 7% | ||

| Roman Catholic: | 14% | Lutheran: | 2% | ||

| Other Christian: | 13% | Presbyterian: | 3% | ||

| Judaism: | 1% | Episcopal: | 3% | ||

| Islam: | 1% | Pentecostal: | 2% | ||

| Other religions: | 4% | Congregational: | 1% | ||

| Non-religious: | 12% | Other/general: | 2% | ||

Virginia is predominantly Protestant; Baptists are the largest single group with thirty percent of the population.[82] Roman Catholics are the second-largest group. Baptist denominational groups in Virginia include the Baptist General Association of Virginia, with about 1,400 member churches, which supports both the Southern Baptist Convention and the moderate Cooperative Baptist Fellowship; and the Southern Baptist Conservatives of Virginia with over 500 affiliated churches, which supports the Southern Baptist Convention.[83][84]

While a small population in terms of the state overall, Jewish people have been long part of its history. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Arlington includes most of Northern Virginia's Catholic churches, while the Diocese of Richmond covers the rest. The Virginia Synod is responsible for the churches of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia, Southern Virginia, and Southwestern Virginia support the various Episcopal churches. In November 2006, fifteen conservative Episcopal churches in the Diocese of Virginia voted to split from the diocese and the larger Anglican Communion church over the issue of sexuality and the ordination of openly gay clergy and bishops. Virginia law allows parishioners to determine their church's affiliation. The resulting property law case is a test for Episcopal churches nationwide, as the diocese claims the church properties of those congregations that want to secede.[85]

About fifty percent of those practicing non-Christian faiths come from India. Others may include Vietnamese Americans and others of Asian descent. Together, those who practice Buddhism and Hinduism form the fastest growing group, and largest of the "Other Religions" group, accounting for one percent of the population. Islam, the second fastest growing religious group, accounts for 0.99% of the population.[86] Non-denominational megachurches in the state include McLean Bible Church and Immanuel Bible Church.

Economy

Virginia's economy is well balanced with diverse sources of income. In 2006, Forbes Magazine named Virginia the best state in the nation for business.[87] As of the 2000 census, Virginia had the highest number of counties and independent cities, fifteen, in the top one-hundred wealthiest jurisdictions in the United States based upon median income. In addition, Virginia tied with Colorado as having the most counties, ten, in the top one-hundred based on per capita income.[88] As of 2007, seven Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in the Richmond area.[89] Virginia has seventeen total Fortune 500 companies, making it rank tenth nationwide. Additionally, ten Fortune 1000 companies are in Northern Virginia, with a total of twenty-nine in the state.[90]

In Southside Virginia from the Hampton Roads area to Richmond and down to Lee County, the economy is based on military installations, and cattle, tobacco and peanut farming. About twenty percent of Virginian jobs are in agriculture, with 47,000 farms, averaging 181 acres (0.28 sq mi; 0.73 km2).[14] Tomatoes surpassed soy as the most profitable crop in Virginia in 2006, with peanuts and hay as other agricultural products.[91] Oysters are an important part of the Chesapeake Bay economy, but declining populations due to disease, pollution, and overfishing have diminished catches.[92] Wineries and vineyards in the Northern Neck and along the Blue Ridge Mountains also have begun to generate income and attract tourists.[93]

Northern Virginia, once considered the state's dairy capital, now hosts software, communication technology, and consulting companies. Fairfax and Loudoun counties in Northern Virginia have the highest and second highest median household income, respectively, of all counties in the United States as of 2006.[94] Virginia has the highest concentration of technology workers of any state.[95] One-third of Virginia's jobs are in the service sector.[9] Computer chips became the state's highest-grossing export in 2006, surpassing its traditional top exports of coal and tobacco, combined.[8] The Dulles Technology Corridor near Dulles International Airport has a high concentration of Internet, communications and software engineering firms.[96]

Many of Northern Virginia's well-educated population work directly for Federal agencies. Many others work for government contractors, including defense and security contractors.[97] Well-known government agencies headquartered in Northern Virginia include the Central Intelligence Agency and the Department of Defense, as well as the National Science Foundation, the United States Geological Survey and the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The Hampton Roads area has the largest concentration of military bases and facilities of any metropolitan area in the world. The largest of the bases is Naval Station Norfolk.[62] The state is second to Alaska in per capita defense spending.[98]

Virginia collects personal income tax in five income brackets, ranging from 3.0% to 5.75%. The sales and use tax rate is 5%. The tax rate on food is 2.5%. There is an additional 1% local tax, for a total of a 5% combined sales tax on most Virginia purchases and a combined tax rate of 2.5% on food.[99] Virginia's property tax is set and collected at the local government level and varies throughout the commonwealth. Real estate is taxed at the local level based on one-hundred percent of fair market value. Tangible personal property also is taxed at the local level and is based on a percentage or percentages of original cost.[100]

Culture

Virginia's historic culture was popularized and spread across America and the South by Washington, Jefferson, and Lee, and their homes represent Virginia as the birthplace of America and of the South.[101] Modern Virginia culture is a subculture in the wider culture of the Southern United States, though it shows elements of the North as well as the South. Although the Piedmont dialect is one of the most famous with its strong influence on Southern American English, a more homogenized American English is favored in Northern and urban areas.[102] The Tidewater dialect is also a distinct local accent.[103]

Besides the general cuisine of the Southern United States, Virginia maintains its own particular traditions. Virginia wine is made in many parts of the state.[93] Smithfield ham, sometimes called Virginia ham, is a type of country ham which is protected by state law, and can only be produced in the town of Smithfield.[104] Virginia furniture and architecture are typical of American colonial architecture. Thomas Jefferson and many of the states early leaders favored the Neoclassical architecture style, leading to its use for important state buildings. The Pennsylvania Dutch and their style can also be found in parts of the state.[78]

Fine and performing arts

The Virginia Foundation for the Humanities works to improve commonwealth's civic, cultural, and intellectual life.[105] The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is a state-funded museum with the largest collection of Fabergé eggs outside of Russia.[106] The Chrysler Museum of Art is home to many pieces, stemming from the Chrysler family collection, including the final sculpture of Gian Lorenzo Bernini.[107] Other museums include the popular Science Museum of Virginia, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum, the Frontier Culture Museum, and the Mariners' Museum. Besides these sites, many open air museums and battlefields are located in the state, such as Colonial Williamsburg, Richmond National Battlefield, and Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts is located in Vienna and is the only national park intended for use as a performing arts center. Wolf Trap hosts the Wolf Trap Opera Company, which produces an opera festival every summer. The Harrison Opera House in Norfolk is home to the official Virginia Opera. The Virginia Symphony Orchestra is based in Hampton Roads. The American Shakespeare Center is located in Staunton, and home to resident and touring theater troupes. Other notable theaters include the Ferguson Center for the Arts, the Barter Theatre, and the Landmark Theater.

Ralph Stanley, Patsy Cline, The Statler Brothers and The Carter Family are award winning Bluegrass and Country music musicians from Virginia. Ella Fitzgerald and Pearl Bailey — celebrated jazz and blues singers of all time — were both from Newport News, Virginia. Bluegrass, Jazz and Blues musician Bruce Hornsby is also a Grammy Award winner from the commonwealth.

Besides native music, like Piedmont blues, bluegrass, and the traditional "mountain music" of Appalachia, Virginia has also launched many internationally successful popular music acts. Hip hop and Rhythm and blues acts like Missy Elliott, Timbaland, The Neptunes, Chris Brown, and Clipse hail from the commonwealth; as does singer-songwriter Jason Mraz and jam bands like the Pat McGee Band and Dave Matthews Band, who continue their strong charitable connection to Charlottesville, Virginia.[108] Influential stage-rock group GWAR also began at Virginia Commonwealth University. Major performance venues in the state include The Birchmere, Nissan Pavilion, the Patriot Center, and the Verizon Wireless Virginia Beach Amphitheater.

Festivals

Many counties and localities host county fairs and festivals. The Virginia State Fair is held at the Richmond International Raceway every September. Fairfax County sponsors Celebrate Fairfax! the second weekend after Memorial Day.[109] In Virginia Beach, the end of September brings the Neptune Festival, celebrating the city, the waterfront, and regional artists.[110]

On the Eastern Shore island of Chincoteague the annual Pony Swim & Auction of feral Chincoteague ponies at the end of July is a unique local tradition expanded into a week-long carnival.[111] The Shenandoah Apple Blossom Festival is a six-day festival held annually in Winchester that includes parades and bluegrass concerts. From 2005 to 2007, Richmond was host of the National Folk Festival. The Northern Virginia Fine Arts Festival is held over four days in May in Reston.[112]

Two important film festivals, the Virginia Film Festival and the VCU French Film Festival, are held annually in Charlottesville and Richmond, respectively. Annual fan conventions in the commonwealth include Anime USA, the national anime convention held in Crystal City, Anime Mid-Atlantic held in various cities, Magfest music and gaming festival, and RavenCon science fiction convention in Richmond.

Media

The Hampton Roads area is the forty-second largest media market in the United States as ranked by Nielsen Media Research, and the Richmond-Petersburg area is sixtieth and Roanoke-Lynchburg is sixty-eighth.[113] There are twenty-one television stations in Virginia, representing each major U.S. network, part of forty-two stations which serve Virginia viewers.[114] About 352 radio stations broadcast in Virginia. The nationally available Public Broadcasting Service, abbreviated as PBS, is headquartered in Arlington. The locally focused Commonwealth Public Broadcasting Corporation, a non-profit corporation which owns public TV and radio stations, has offices around the state.[115]

Major newspapers in the commonwealth include The Virginian-Pilot, based in Norfolk, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, and The Roanoke Times. The Times-Dispatch has a daily subscription of 186,441, slightly more than the Pilot at 183,024, fiftieth and fifty-second in the nation respectively, while the Roanoke Times has about 97,000 daily subscribers.[116][117] Several Washington, D.C. papers are based in Northern Virginia, such as The Washington Examiner and The Politico. The nation's widest circulated paper, USA Today, is headquartered in McLean. The Arlington based Freedom Forum is an organization dedicated to free press and journalistic free speech.[118] Besides traditional forms of media, Virginia is home to telecommunication companies such as Sprint Nextel and XO Communications. The Dulles Technology Corridor contains the "pathways that carry more than half of all traffic on the Internet."[96]

Education

Public K-12 schools in Virginia are generally operated by the counties and cities, and not by the state. Virginia's educational system consistently ranks in the top ten states on the U.S. Department of Education's National Assessment of Educational Progress, with Virginia students outperforming the average in all subject areas and grade levels tested.[119] The 2008 Quality Counts report ranked Virginia's K-12 education fifth best in the country.[120] All school divisions must adhere to educational standards set forth by the Virginia Department of Education, which maintains an assessment and accreditation regime known as the Standards of Learning to ensure accountability.[121] As of 2004, Virginia has a 79.3% graduation rate, which is the twelfth highest in the nation.[122]

There are a total of 1,863 local and regional schools in the commonwealth, including three charter schools, and an additional 104 alternative and special education centers in 134 school divisions.[123] Besides the general public schools in Virginia, there are Governor's Schools and selective magnet schools. Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology, a public school which requires an application, is ranked as the best public high school in the nation.[124] The Governor's Schools are a collection of more than forty regional selective magnet high schools and summer programs intended for gifted students.[125] The Virginia Council for Private Education oversees the regulation of private schools.

Individual Virginia public high schools are often well rated, with public Langley High School ranked thirty-seventh best public high school in the nation according to U.S. News & World Report, and H-B Woodlawn in Arlington twelfth according to The Washington Post Challenge Index.[124][126] Northern Virginia schools also pay the test fees for students to take Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate exams, and Alexandria and Arlington Counties lead the nation in college course tests.[127]

Two of the U.S. top ten public universities are located in Virginia, according to the U.S. News and World Report annual college rankings. The University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson, is ranked #2, and the College of William and Mary, the second-oldest college in America, is ranked #6.[128] James Madison University has been the number one public master's level university in The South since 1993.[129] Virginia is also home to the Virginia Military Institute, the oldest state military college in the U.S. and a top public liberal arts college.[130] Virginia Commonwealth University is the largest university in Virginia with over 30,000 students, followed closely by George Mason University.[131] Virginia Tech and Virginia State University are the land-grant universities of the state. The state also operates twenty-three community colleges on forty campuses serving over 240,000 students.[132]

Health

Unlike their nation-leading education system, Virginia has a mixed health record. Virginia falls twenty-third highest among United States in both percentage of residents who exercise, seventy-eight percent, and in the rate of pre-mature deaths, 855.6 per 100,000.[133][134] Though Virginia is ranked as the twenty-first overall healthiest state, it has the fifth highest immunization coverage in the nation according to the United Health Foundation's Health Rankings 2006.[135] As of 2002, Virginia had a 23.7% obesity rate in adults, and thirty percent of Virginia's ten to seventeen year olds were overweight or obese, which is the twenty-fifth lowest percent in the country.[136] As of 2005, only 86.4% of Virginians have health insurance.[137]

There are eighty-six hospitals in Virginia listed with the United States Department of Health and Human Services.[138] Notable examples include Inova Fairfax Hospital, the largest hospital in the Washington Metropolitan Area, and the Medical College of Virginia (MCV), the medical school of Virginia Commonwealth University, which is home to the nation's oldest organ transplant program. The University of Virginia Medical Center, part of the University of Virginia Health System, which according to U.S.News & World Report has the eight ranked endocrinology specialty in the nation, and the best in the South.[139] Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, part of the Hampton Roads based Sentara Health System, is also nationally ranked, and was the site of the first successful in-vitro fertilization birth.[140][141]

Transportation

As of 2007, the Virginia state government owns and operates 84.6% of roads in the state, instead of the local city or county authority.[142] 57,884 miles (93,155 km) of the total 68,429 miles (110,126 km) are run by the Virginia Department of Transportation, making it the third largest state highway system in the United States.[143] Virginia's road system is ranked as the eighteenth best in the nation.[144] While the Washington Metropolitan Area has the second worst traffic in the nation, Virginia as a whole has the twenty-first lowest congestion.[145] With low disbursements for both roads and bridges, and a low road fatality rate, Virginia has a good system with a tight budget.[146] The average commute time is 22.2 minutes.[147]

Virginia has five major airports: Washington Dulles International, Washington Reagan National, Richmond International, Norfolk International and Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport.[148] Seventy-one airports serve the state's aviation needs.[149] Virginia has Amtrak passenger rail service along several corridors, and Virginia Railway Express maintains two commuter lines into Washington, D.C. from Fredericksburg and Manassas. The Washington Metro rapid transit system currently serves Northern Virginia as far west as Fairfax County, although expansion plans call for Metro to reach Dulles Airport in Loudoun County by 2015.[150] The Virginia Department of Transportation operates several free ferries throughout Virginia, the most notable being the Jamestown-Scotland ferry which crosses the James River in Surry County.[151]

Law and government

In colonial Virginia, free men elected the lower house of the legislature, called the House of Burgesses, which together with the Governor's Council, made the "General Assembly." Founded in 1619, the Virginia General Assembly is still in existence as the oldest legislature in the Western Hemisphere.[39] The modern government is ranked with an "A-", the highest grade in the nation, by the Pew Center on the States, an honor it shares with two others.[6]

Virginia functions under the 1971 Constitution of Virginia, the commonwealth's seventh constitution, which provides for fewer elected officials than the previous constitution, with a strong legislature and a unified judicial system. Modeled on the federal structure, the government is divided in three branches: legislative, executive, and judicial. The legislative branch is the General Assembly, a bicameral body whose 140 members write the laws for the commonwealth. It is stronger than the executive, as incumbent governors cannot run for re-election, and the General Assembly selects judges and justices.[152] The current governor is Tim Kaine. Other members of the executive branch include the Lieutenant Governor and the Attorney General. The judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of Virginia, the Virginia Court of Appeals, the General District Courts and the Circuit Courts.[153]

The Code of Virginia is the statutory law, and consists of the codified legislation of the General Assembly. The Virginia State Police are the largest law enforcement agency in Virginia, and the Virginia Capitol Police are the oldest police department in the United States.[154] The Virginia National Guard consists of 7,500 soldiers in the Virginia Army National Guard and 1,200 airmen in the Virginia Air National Guard.[155] In 2004, Virginia had the fifteenth lowest rate of violent crime per capita in the United States, but also had the fifth most race related hate crimes.[156] The "total crime risk" is twenty-nine percent under the national average.[147] Since the 1982 resumption of capital punishment in Virginia, ninety-eight people have been executed, second most in the nation.[157]

Politics

Virginia's politics in the last century reflects a shift from a largely rural, politically Southern and conservative racially divided single-party state to a more urbanized, pluralistic political environment.[158] African Americans were effectively disfranchised until after passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s, which was one of the catalysts for their early 20th century Great Migration to northern cities.[159] Enfranchisement and immigration of other groups, especially Hispanics, have placed growing importance on minority voting.[160] Politically moderate urban and growing suburban areas, including Northern Virginia, are the Democratic base.[161] Rural Virginia moved to support the Republican Party in response to their "southern strategy."[162] Portions of Southwest Virginia influenced by unionized coal mines, college towns such as Charlottesville and Blacksburg, and southeastern counties in the Black Belt Region have remained more likely to vote Democratic.[163][164]

While Virginia's Governor is a Democrat, the Lieutenant Governor is a Republican, and Republican Robert McDonnell became Attorney General by 360 votes following a legally mandated recount of ballots for that race in 2005.[165] In the 2004 U.S. Presidential election, Fairfax County and other Northern Virginia counties voted for the Democrat for the first time in forty years.[166] In the 2007 state elections, the Democrats regained control of the State Senate, and narrowed the Republican majority in the House of Delegates to eight votes.[167] Virginia is classified as a "swing state" for future presidential elections.[5]

The election of Democrat Jim Webb as one of Virginia's two U.S. Senators in the 2006 Virginia Senate election may have demonstrated disaffection with incumbent administration's performance.[168] John Warner, a Republican, has long held Virginia's other seat in the U.S. Senate, but he has announced his intention not to seek reelection in 2008.[169] Both of Virginia's Senators are former Secretaries of the Navy. Of state's eleven seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, Republicans hold eight and Democrats hold three.

Sports

Virginia is by far the most populous U.S. state without a major professional sports league franchise.[170] The reasons for this include the lack of any dominant city or market within the state and the proximity of teams in Washington, D.C. which has franchises in all four major sports.[171] Virginia is home to many minor league clubs, especially in baseball and soccer, and the Washington Redskins have Redskins Park, their headquarters and training facility, in Ashburn, Virginia.[172] Virginia has many professional caliber golf courses including the Greg Norman course at Lansdowne Resort and Upper Cascades, Kingsmill Resort, home of the Michelob ULTRA Open.

The Washington Nationals and Baltimore Orioles also have followings due to their proximity to the state, and both are broadcast in the state on MASN.[173] When the New York Mets ended their long affiliation with the Norfolk Tides in 2007, the Orioles adopted the minor league club.[174] Other regional teams include the Cincinnati Reds and the Atlanta Braves, whose top farm team, the Richmond Braves, is located in the capital.

Virginia is home to two NASCAR tracks currently on the Sprint Cup schedule, Martinsville Speedway and Richmond International Raceway. Norfolk born Rex White won the NASCAR Grand National in 1962 and 1963. Current Virginia drivers in the series include brothers Jeff Burton and Ward Burton, Ricky Rudd, Denny Hamlin, and Elliot Sadler.[175] Former Cup tracks include South Boston Speedway, Langley Speedway, Southside Speedway, and Old Dominion Speedway.

Virginia does not allow state appropriated funds to be used for either operational or capital expenses for intercollegiate athletics.[176] Despite this, both the University of Virginia Cavaliers and Virginia Tech Hokies have been able to field competitive teams in the Atlantic Coast Conference and maintain modern facilities. The Virginia-Virginia Tech rivalry is followed statewide. Virginia has several other universities that compete in Division I of the NCAA, particularly in the Colonial Athletic Association. Three historically black schools compete in the Division II Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association, and two others compete in Division I MEAC. Several smaller schools compete in the Old Dominion Athletic Conference and the USA South Athletic Conference of NCAA Division III. The NCAA currently holds its Division III championships in football, men's basketball, volleyball and softball in Salem.[177]

State symbols

The state nickname is the oldest symbol, though it has never been made official by law. Virginia was given the title, "Dominion", by King Charles II of England at the time of The Restoration, because it had remained loyal to the crown during the English Civil War, and the present moniker, "Old Dominion" is a reference to that title.[178] The other nickname, "Mother of Presidents," is also historic, as eight Virginians have served as President of the United States, including four of the first five: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. Additionally, Virginian Sam Houston served as president of the Republic of Texas.

Virginia is the only state to have the same plant for state flower and state tree.[179] The majority of the symbols were made official in the late 20th century, though the state motto and seal have been official since Virginia declared its independence.[180] Virginia currently has no state song, as the now state song emeritus, "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny", was retired in 1997.[181]

|

See also

- List of historic houses in Virginia

- List of people from Virginia

- Lost counties, cities, and towns of Virginia

- Scouting in Virginia

- List of museums in Virginia

References

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. 29 April 2005. Retrieved 2006-11-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Martz, Michael (December 28, 2007). "Virginia's population tops 7.7 million". Richmond Times Dispatch. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Introduction to Virginia

- ^ Jamestown Ball

- ^ a b Balz, Dan (October 12, 2007). "Painting America Purple". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Somashekhar, Sandhya (March 4, 2008). "Government Takes Top Honors in Efficiency". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Colonial Williamsburg". Virginia is for Lovers. August 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ a b Richards, Gregory (February 24, 2007). "Computer chips now lead Virginia exports". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "Virginia facts". National Geographic. April 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Supreme Court Rules for Virginia in Potomac Conflict". The Sea Grant Law Center. University of Mississippi. 2003. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Rivers and Watersheds". The Geology of Virginia. College of William and Mary. February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Largest Earthquake in Virginia". United States Geological Survey. January 25, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Economic Resources". The Geology of Virginia. College of William and Mary. January 22, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ a b "Virginia's Agricultural Resources". Natural Resource Education Guide. Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. January 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|publisher=and|work= - ^ "Physiographic Regions of Virginia". The Geology of Virginia. College of William and Mary. February 16, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Climate of Virginia". GEOG 202. Radford University. March 14, 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Gaston impact". NOAA. September 3, 2004. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Natural Hazards : Thunderstorms". Virginia Business Emergency Survival Toolkit. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Natural Hazards : Tornadoes". Virginia Business Emergency Survival Toolkit. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "The Natural Communities of Virginia". Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ "Advisory 01/07: The Hot Get Hotter? Urban Warming and Air Quality". University of Virginia Climatology Office. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "Immigration Impact: Virginia". Federation for American Immigration Reform. 2005. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ "Virginia's Forest Resources". Natural Resource Education Guide. Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. January 21, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|publisher=and|work= - ^ "Shenandoah National Park - Forests". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-09-10.

- ^ "Shenandoah National Park - Mammals". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ Cochran, Bill (April 21, 2005). "Mountain lions are back -- maybe". The Roanoke Times. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Shenandoah National Park - Birds". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ "Shenandoah National Park - Fish". National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ "Bay Biology". Chesapeake Bay Program. January 5, 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Park Locations". Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation. November 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Jamestown's Cultural Roots Focus of Smithsonian Folklife Festival; Three Cultures That Converged At Jamestown Meet Again On The National Mall" (PDF). Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ Ramsey, Inez (March 16, 2003). "Virginia's Indians, Past & Present". American History Resources. James Madison University. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Native Peoples in Early Colonial Virginia". University of Richmond. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ Harris, Andrew (September 20, 2005). "The First Virginia". Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Trevelyan, Raleigh. Sir Walter Raleigh. pp. 77–78. ISBN 080507502X. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "The First Charter of Virginia; April 10, 1606". The Avalon Project. Yale University. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Jamestown - Timeline". The Literature of Justification. Lehigh University. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Wallenstein, Peter (2007). Cradle of America: Four Centuries of Virginia History. University Press of Kansas. pp. 17, 104, 114. ISBN 978-0-7006-1507-0.

- ^ a b Helderman, Rosalind S. (May 7, 2006). "Latest Budget Standoff Met With Shrugs". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Indentured Servants in the U.S." History Detectives. Public Broadcasting Service. 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "Unthinking Decision? Why Did Slavery Emerge in Virginia?". Digital History Reader. Virginia Tech. 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ "Genealogy". Virginia Historical Society. May 15, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "History 1600s". Virginia's First People. 2005. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "A Brief History of Williamsburg". City Manager's Office. Williamsburg, Virginia. October 9, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Signers of the Declaration (Richard Henry Lee)". National Park Service. April 13, 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Declaration of Independence". United States Library of Congress. June 19, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Schwartz, Stephan A. (May, 2000). "George Mason : Forgotten Founder, He Conceived the Bill of Rights". Smithsonian (31.2): 142.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Constitution of Virginia; June 29, 1776". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ Cooper, Jean L. (2007). A Guide to Historic Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia. The History Press. p. 58. ISBN 1-596-29173-7.

- ^ "The Story of Virginia; Becoming Americans". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ "Fun Facts for the Charlotte Region". United States Census Bureau. April 26, 2004. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Davis, David Brion (2006). Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. Oxford University Press. pp. 125, 208–210. ISBN 0-19-514073-7.

- ^ "Census Data for Year 1860". Historical Census Browser. University of Virginia. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Du Bois, W.E.B. (1998) [1935]. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880. New York: Harcourt Brace/The Free Press (reprint). p. 598. ISBN 0684856573.

- ^ "Virginia's Constitutional Convention of 1901–1902". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ Pildes, Richard H. (2000). "Democracy, Anti-Democracy and the Canon". Constitutional Commentary. 17: 12. doi:10.2139/ssrn.224731.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Wallenstein, Peter (1997). "Not Fast, But First: The Desegregation of Virginia Tech". VT Magazine. Virginia Tech. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work=|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia: Massive Resistance". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ^ "Closing Prince Edward County's Schools". Virginia Historical Society. January 11, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "County & County Equivalent Areas". United States Census Bureau. April 19, 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Population in Greater Richmond Virginia". Greater Richmond Partnership, Inc. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b "About Hampton Roads". Hampton Roads, Virginia is America's First Region. December 21, 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Fairfax County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. August 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Doing Business in Fairfax County". Fairfax County Economic Development Authority. June 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ Davenport, Coral (January 23, 2006). "In a fast-growing county, sprawl teaches hard lessons". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Battiata, Mary (November 27, 2005). "Silent Streams". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Group Tours". Virginia's Roanoke Valley. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "All About Suffolk". Suffolk. February 12, 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c "Virginia - ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006". United States Census Bureau. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ "Population and Population Centers by State" (TXT). United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ "Virginia ProEnglish". ProEnglish.org. November 20, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Virginia Selected Social Characteristics in the United States". United States Census Bureau. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ "Virginia - QT-P13. Ancestry: 2000". United States Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (2005). Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas: Restoring the Links. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ name=demographics>"Virginia's First People".

- ^ "Scots-Irish Sites in Virginia". Virginia Is For Lovers. January 3, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ a b Keller, Christian B. (2001). "Pennsylvania and Virginia Germans during the Civil War". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. 109. Virginia Historical Society: 37–86. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ "State's Hispanic population nearly triples since 1990". University of Virginia. February, 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Wood, Joseph (1997). "Vietnamese American Place Making in Northern Virginia". Geographical Review. 87 (1): 58–72. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS). CUNY Key Findings. 2001.

- ^ "What is your religion... if any?". USA Today. 2001. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ^ Vegh, Steven G. (November 10, 2006). "2nd Georgia church joins moderate Va. Baptist association". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "SBCV passes 500 mark". Baptist Press. November 20, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ Boorstein, Michelle (November 14, 2007). "Trial Begins in Clash Over Va. Church Property". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Religion by Location". Adherents.com. April 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Virginia Rated Top State for Business" (PDF). Virginia Economic Development Partnership. 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ "Per capita personal income". Regional Economic Information System. Bureau of Economic Analysis. April 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ "Fortune 500 2007: Cities". Money. April 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Fortune 500 2007: States: Virginia". Money. April 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ McNatt, Linda (October 17, 2007). "Tomato moves into the top money-making spot in Virginia". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "NOAA Working to Restore Oysters in the Chesapeake Bay". NOAA. March 31, 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Sampson, Zinie Chen (October 26, 2007). "Virginia wineries emerge, attracting tourists". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Amy, Goldstein (August 30, 2006). "D.C. Suburbs Top List Of Richest Counties". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kazmierczak, Matthew (2007-04-24). "D.C. Capital Region Is A Growing High-Tech Hub". American Electronics Association. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ a b "D.C. Dotcom". Time. 2000-08-06. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fox, Justin (February 8, 2007). "The Federal Job Machine". Time. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Federal Domestic Spending Up 9 Percent in 2001". United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau. 2002. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ "State Sales Tax Rates". Federation of Tax Administrators. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- ^ "Virginia Tax Facts" (PDF). Virginia Department of Taxation. February 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ^ McGraw, Eliza (June 24, 2005). Two Covenants: Representations of Southern Jewishness. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-3043-5. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Clay III, Edwin S. (May 9, 2005). "Virginia's Many Voices". Bacon's Rebellion. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dialects Of Virginia". International Dialects of English Archive. University of Kansas. November 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Code of Virginia > 3.1-867". LIS. July 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Mission & History". Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ "Art on View". Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. December 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Collections - Bust of the Savior". Chrysler Museum of Art. 2006. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ^ "Charities". Dave Matthews Band. November 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Celebrate Fairfax! Festival". Celebrate Fairfax, Inc. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ^ "Neptune Festival". Virginia Beach Neptune Festival. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ^ "Chincoteague Firemen's Carnival, Pony Swim, Pony Auction". Chincoteague Chamber of Commerce. February 21, 2003. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Virginia Festivals and Events". FestivalsandEvents.com. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ^ "210 Designated Market Areas - 03-04". Nielsen Media. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ^ "U.S. Television Stations in Virginia". Global Computing. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "About Us". The Community Idea Stations. 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "2007 Top 100 Daily Newspapers in the U.S. by Circulation" (PDF). BurrellesLuce. 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- ^ "Landmark Metro Newspapers: The Roanoke Times". Landmark Communications, Inc. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Journalist deaths in Iraq compare to those of WW2". Reuters. The New Zealand Herald. May 31, 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "State Education Data Profiles". National Assessment of Educational Progress. Retrieved 2007-12-25..

- ^ "Quality Counts 2008" (PDF). Education Week. January 9, 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "Virginia School Report Card". Virginia Department of Education. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Measuring Virginia's High School Graduation Rate". Virginia Performs. 2005. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Local and Regional Schools and Centers". Virginia Department of Education. November 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ a b Glod, Maria (November 30, 2007). "Thomas Jefferson Put at Top of Class". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Virginia Governor's School Program". Virginia Department of Education. October 6, 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); External link in|work= - ^ "2007 Challenge Index". The Washington Post. May 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mathews, Jay (December 13, 2007). "Alexandria, Arlington Schools Lead Nation in AP, IB Testing". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Top Public National Universities". U.S. News and World Report. 2008. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ "JMU Holds Top Public Regional Rank for 14th Year in 'U.S. News' Survey". Public Affairs. James Madison University. August 17, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Top Public Liberal Arts Colleges". America's Best Colleges 2007. U.S. News and World Report. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "2006-2007 Fall Headcount Enrollment". State Council of Higher Education for Virginia. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "Fast Facts". Virginia’s Community Colleges. 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "Statemaster Health Statistics Physical Exercise by State". Statemaster. 2002. Retrieved 2008-02-06.