King Kong (1933 film): Difference between revisions

Tritium h3 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Tritium h3 (talk | contribs) m →Reception: fixed ref |

||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

The film received positive reviews on its first release, although Joe Bigelow of [[Variety (magazine)|''Variety'']] claimed that the film was a good adventure if the viewer is "willing to suspend disbelief and after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phony atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power."<ref>[http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117792322 ''Variety''] review - Joe Bigelow, 1933.</ref> The ''New York Times'' found it a fascinating adventure film: "Imagine a fifty-foot beast with a girl in one paw climbing up the outside of the Empire State Building, and after putting the girl on a ledge, clutching at airplanes, the pilots of which are pouring bullets from machine guns into the monster's body".<ref> {{cite news | first=Mordaunt | last=Hall | title=King Kong | date=[[March 3]], [[1933]] | publisher=New York Times | url=http://movies2.nytimes.com/mem/movies/review.html?title1=&title2=KING%20KONG%20%28MOVIE%29&reviewer=Mordaunt%20Hall&pdate=&v_id=27391}}</ref> |

The film received positive reviews on its first release, although Joe Bigelow of [[Variety (magazine)|''Variety'']] claimed that the film was a good adventure if the viewer is "willing to suspend disbelief and after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phony atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power."<ref>[http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117792322 ''Variety''] review - Joe Bigelow, 1933.</ref> The ''New York Times'' found it a fascinating adventure film: "Imagine a fifty-foot beast with a girl in one paw climbing up the outside of the Empire State Building, and after putting the girl on a ledge, clutching at airplanes, the pilots of which are pouring bullets from machine guns into the monster's body".<ref> {{cite news | first=Mordaunt | last=Hall | title=King Kong | date=[[March 3]], [[1933]] | publisher=New York Times | url=http://movies2.nytimes.com/mem/movies/review.html?title1=&title2=KING%20KONG%20%28MOVIE%29&reviewer=Mordaunt%20Hall&pdate=&v_id=27391}}</ref> |

||

Susan Sontag, in her 1964 essay [[Notes on "Camp"]] {{cite journal | first=Susan | last=Sontag | title=Notes on "Camp" | journal=Partisan Review | date=1964 | url=http://interglacial.com/~sburke/pub/prose/Susan_Sontag_-_Notes_on_Camp.html}}, includes the film as part of the canon of Camp. It should be noted, however, that this is not necessarily meant to denigrate the film; Sontag considers "Camp" a sensibility detached from content, and thus many works of high camp, even intentional camp, can be considered good and worthwhile art. |

Susan Sontag, in her 1964 essay [[Notes on "Camp"]] <ref>{{cite journal | first=Susan | last=Sontag | title=Notes on "Camp" | journal=Partisan Review | date=1964 | url=http://interglacial.com/~sburke/pub/prose/Susan_Sontag_-_Notes_on_Camp.html}}</ref>, includes the film as part of the canon of Camp. It should be noted, however, that this is not necessarily meant to denigrate the film; Sontag considers "Camp" a sensibility detached from content, and thus many works of high camp, even intentional camp, can be considered good and worthwhile art. |

||

More recently, [[Roger Ebert]] wrote in his Great Films review that the effects are not up to modern standards, but "there is something ageless and primeval about ''King Kong'' that still somehow works."<ref> {{cite news | first=Roger | last=Ebert | title=King Kong (1933) | date=[[February 3]], [[2002]] | publisher=Chicago Sun Times | url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=%2F20020203%2FREVIEWS08%2F202030301%2F1023}}</ref> |

More recently, [[Roger Ebert]] wrote in his Great Films review that the effects are not up to modern standards, but "there is something ageless and primeval about ''King Kong'' that still somehow works."<ref> {{cite news | first=Roger | last=Ebert | title=King Kong (1933) | date=[[February 3]], [[2002]] | publisher=Chicago Sun Times | url=http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=%2F20020203%2FREVIEWS08%2F202030301%2F1023}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:41, 31 May 2008

| King Kong | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Merian C. Cooper Ernest B. Schoedsack |

| Written by | Merian C. Cooper (story) Edgar Wallace (story) James Ashmore Creelman (screenplay) Ruth Rose (screenplay) |

| Produced by | Merian C. Cooper Ernest B. Schoedsack David O. Selznick (executive producer) |

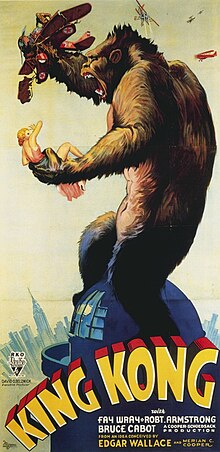

| Starring | Fay Wray Robert Armstrong Bruce Cabot |

| Cinematography | Eddie Linden J.O. Taylor Vernon Walker |

| Music by | Max Steiner |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures, Inc. |

Release dates | March 2, 1933 (US release) |

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Country | |

- This is about the original movie and novel. For other uses and adaptations, see King Kong.

King Kong is a landmark black-and-white adventure film about a gigantic gorilla named "Kong" and how he is captured and brought to civilization against his will.

The film was made by RKO and was originally written for the screen by Ruth Rose and James Ashmore Creelman, based on a concept by Merian C. Cooper. A major on-screen credit for Edgar Wallace, sharing the story with Cooper, was unearned, as Wallace became ill soon after his arrival in Hollywood and died without writing a word, but Cooper had promised him credit.[1] A novelization of the screenplay actually appeared in 1932, a year before the film, adapted by Delos W. Lovelace, and contains descriptions of scenes not present in the movie.

The film was directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, starred Fay Wray, Robert Armstrong and Bruce Cabot, and is notable for Willis O'Brien's ground-breaking stop-motion animation, Max Steiner's musical score and Fay Wray's performance as the ape's love interest. King Kong premiered in New York City on March 2, 1933 at Radio City Music Hall.

Influences

King Kong was influenced by the "Lost World" literary genre, particularly Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World (1912) and Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Land That Time Forgot (1918), which depicted remote and isolated jungles teeming with prehistoric life. Furthermore, a film adaptation of the Doyle novel made movie history in 1925, with special effects by Willis O'Brien and the Kong crew.

In the early 20th century, few zoos had primate exhibits so there was popular demand to see them on film. William S. Campbell specialized in monkey-themed films with Monkey Stuff and Jazz Monkey in 1919, with Prohibition Monkey following in 1920. Kong producer Schoedsack had earlier monkey experience directing Chang in 1927 (also with Cooper) and Rango in 1931, both of which prominently featured monkeys in authentic jungle settings.

Capitalizing on this trend, "Congo Pictures" released the hoax documentary Ingagi in 1930, advertising the film as "an authentic incontestable celluloid document showing the sacrifice of a living woman to mammoth gorillas." Ingagi was an unabashed black exploitation film, immediately running afoul of the Hollywood code of ethics, as it implicitly depicted black women having sex with gorillas, and baby offspring that looked more ape than human.[2] The film was an immediate hit, and by some estimates it was one of the highest grossing movies of the 1930s at over $4 million. Although producer Merian C. Cooper never listed Ingagi among his influences for King Kong, it's long been held that RKO green-lighted Kong because of the bottom-line example of Ingagi and the formula that "gorillas plus sexy women in peril equals enormous profits".[3]

Both directors (including Cooper, author of the original idea) fought in World War I, and were probably influenced by World War I propaganda posters. One poster in particular showed Germany like a bloodthirsty ape seizing a helpless girl in its hand.[4].

Paul du Chaillu's travel narrative Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa (1861) was a favorite of Cooper's when he was a child. The gorilla chase scene in the book was yet another inspiration for the film.

The biggest influence on Kong was, in many ways, the 1931 film project Creation, being developed by Willis O'Brien. Until Cooper, in his capacity as an RKO executive, screened its test footage, he had great doubts that he could make his gorilla picture. O'Brien's techniques were the answer, and Cooper ordered that production shelved and put its crew to work on his own.

Plot

The film starts off in 1933 New York, during the depths of the Great Depression. Carl Denham, a film director famous for shooting animal pictures in remote and exotic locations, is unable to hire an actress to star in his newest project and so wanders the streets searching for a suitable girl. He chances upon unemployed Ann Darrow, as she is caught trying to steal an apple. Denham pays off the grocer then buys Ann a meal and offers her the lead role in his latest installment. Although Ann is apprehensive, she has nothing to lose and eagerly agrees.

They set sail aboard the Venture, an old tramp steamer that travels for weeks in the direction of Indonesia, where Denham claims they will be shooting. Despite his ongoing declarations that women have no place on board ships, the ship's first mate Jack Driscoll is obviously becoming attracted to Ann. Denham takes note of the situation and informs Driscoll he has enough trouble without the complications of a seagoing love affair. Driscoll sneers at the suggestion, reminding Denham of his toughness in past adventures. Denham's reply outlines the theme of both the movie he is making and the one in which he is a character: "The Beast was a tough guy too. He could lick the world, but when he saw Beauty, she got him. He went soft. He forgot his wisdom and the little fellas licked him."

After maintaining secrecy throughout the trip, Denham finally tells Driscoll and Captain Englehorn that they're searching for an uncharted island. Denham says that the skipper of a freighter gave him the only map that shows its location, having received it in turn from a native of the island who had been swept out to sea. Denham then describes something monstrous connected to the island, a legendary entity known to the islanders as "Kong".

As the Venture creeps through the fog surrounding the island, the crew hear drums in the distance. Finally arriving at the island's shore, they see a native village perched on a peninsula, cut off from the bulk of the island by an enormous wall. A landing party, including the filmmaker and his leading lady, goes ashore and encounters the natives, who are about to hand over a girl to Kong as a ritual sacrifice. Although Denham, Englehorn, Jack and Ann are hiding behind foliage, the native chief spots them and approaches the troop. Captain Englehorn is able to understand the native speech, and at Denham's urging makes friendly overtures to the chief. When he gets a clear look at Ann, the chief begins speaking with great energy. Englehorn translates this as "look at the golden woman!" The chief proposes to swap six native women for Ann, an offer Denham delicately declines as he and his party edge away from the scene, assuring the chief that they will return tomorrow to get better acquainted.

Back on the Venture, Jack and Ann openly express their love for each another. When Jack is called away to the captain's quarters, a stealthy contingent of natives captures Ann, takes her back to the wall and presents her to Kong in an elaborate ceremony. Kong soon emerges from the jungle and he is revealed to be a giant gorilla. The Venture crew returns to the village and takes control of the wall; the other half of the crew then go after Kong, encountering an enraged Stegosaurus and a territorial Brontosaurus.

Up ahead in a jungle clearing, Kong places Ann in the cleft of a dead tree. He then doubles back and confronts the pursuing crewmembers as they are crossing a deep ravine by way of an enormous fallen log. Kong shakes them off, killing all except Driscoll and Denham. Driscoll, who had grabbed some vines and ascended the chasm, continues the chase while Denham returns to the village. Meanwhile, a Tyrannosaurus rex is breaks through the forest and attempts to eat Ann. Kong rushes back and a long struggle between the two titans ends when Kong pries open the dinosaur's jaw until it breaks. Kong takes Ann up to his mountain lair, where a plesiosaur emerges from a bubbling swamp and tries to strangle Kong, who kills it with ease. Kong then inspects his blonde prize and begins to caress her, tearing off pieces of her clothing and tickling her. Jack interrupts the proceedings by knocking over a boulder. When the gorilla leaves Ann to investigate the noise, a pterosaur swoops from the sky and clutches Ann in its talons. A final fight ensues and the pterodactyl is strangled and is sent tumbling down the cliff face. While Kong is distracted, Jack rescues Ann and takes her back to the native village. Kong chases them, breaks through the large door of the wall and rampages through the village, killing many of the natives. Denham hurls a gas bomb, knocking Kong out, whereupon he exults in the opportunity to take the giant back to New York: "He's always been King of his world. But we'll teach him fear! We're millionaires, boys! I'll share it with all of you! Why, in a few months, his name will be up in lights on Broadway! Kong! The Eighth Wonder of the World!"

The next scene begins with those very words in lights on a theater marquee. Along with hundreds of curious New Yorkers, Denham, Driscoll and Ann are in evening wear for the gala event. The curtain lifts, and Denham presents a subdued and manacled Kong to the stunned audience. All goes well until photographers, using the blinding flashbulbs of the era, begin snapping shots of Ann and her jack, who is now her fiancé. Under the impression that the flashbulbs are attacking Ann, Kong breaks free of his bonds and escapes from the theater. He rampages through the city streets, destroying an elevated train and killing several citizens.

Kong finds Ann and carries her to the top of the Empire State Building. The military dispatches four Curtiss Falcon airplanes to destroy Kong. Once Kong notices the planes are heading towards him, the ape gently sets Ann down on the building's observation deck and climbs atop the dirigible mooring mast, trying to fend off the attackers. When one ventures too close, he manages to swat it down, but in the end is mortally wounded by machine-gun fire and plummets to his death in the street below. Denham picks his way to the front of the crowd, where a cop remarks "Well Denham, looks like the airplanes got him." Denham replies, "It wasn't the airplanes. It was beauty killed the beast."

Production

In the original script, the gorilla is named "Kong". The film was then entitled The Eighth Wonder and press booklets were sent off to thousands of movie theaters in 1932 to excite the theatre owners into placing "The Eighth Wonder" onto their advertisements. The "King" was added to the title by studio publicists. Apart from the opening titles, the only time the name "King Kong" appears in the picture is on the marquee above the theater where Kong is being exhibited, and the marquee was in fact added to the scene as an optical composite after the live footage of the theater entrance had been shot. However, Denham does refer to Kong in his speech as "a king and a god in the world he knew."

The giant gate used in the 1933 movie was burned along with other old studio sets for the burning of Atlanta scene in Gone with the Wind. The gate was originally constructed for the 1927 Biblical epic The King of Kings. It can also be seen in the Bela Lugosi serial The Return of Chandu.

Some jungle scenes were filmed on the same sound stage set as those in The Most Dangerous Game, which was filmed during the day King Kong was being shot at night, and also featured Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong in prominent roles. Other jungle sequences were filmed on Catalina Island.[5] One of the several original metal armatures used to bring Kong to life, as well as other original props from the 1933 film, can be seen in the book It Came From Bob's Basement, a reference to long-time prop collector Bob Burns, who lives in Los Angeles. One armature was on display in London until a few years ago in the now-closed Museum of the Moving Image. Burns recently sold his Kong armature to Peter Jackson, who also bought all the original Kong dinosaur armatures from Forrest J Ackerman.[6]

Cast

- Fay Wray as Ann Darrow

- Robert Armstrong as Carl Denham

- Bruce Cabot as Jack Driscoll

- Frank Reicher as Captain Englehorn

- Sam Hardy as Charles Weston

- Noble Johnson as Native Chief

- James Flavin as Second Mate Briggs

Significance

Although King Kong was not the first important Hollywood film to have a thematic music score (many silent films had multi-theme original scores written for them), it's generally considered to be the most ambitious early film to showcase an all-original score, courtesy of a promising young composer, Max Steiner.

It was also the first hit film to offer a life-like animated central character in any form. Much of what is done today with CGI animation has its conceptual roots in the stop motion animation that was pioneered in King Kong. Willis O'Brien, credited as "Chief Technician" on the film, has been lauded by later generations of film special effects artists as an outstanding genius of founder status.

At the end of the scene where Kong shakes the crew members off the log, he then goes after Driscoll, who is hiding in a small cave just under the ledge. The scene was shot using the miniature set, a mockup of Kong's hand and a rear-projected image of Driscoll in the cave. This is not the first known use of miniature rear projection, but it certainly is among the most famous of early attempts.

Many shots in King Kong featured optical effects by Linwood G. Dunn, who was RKO's optical technician for decades. Dunn did optical effects on Citizen Kane and the original Star Trek TV series, as well as hundreds of other films and shows. In the 1990s, Dunn co-invented an electronic 3-D system now used for micro-surgery in hospitals and in the military, as well as co-inventing a video projection system with better resolution than 35mm film that is used in modern cinemas.

During the film's original 1933 theatrical release, the climax was presented in Magnascope. This is where the screen opens up both vertically and horizontally. Cooper had wanted to wow the audience with the Empire State Building battle in a larger-than-life presentation. He had done this earlier for his earlier film Chang, during the climactic elephant stampede.

Censorship

The first version of the film was test screened to an audience in San Bernardino, California in January 1933, before the official release. At that time the film contained a scene showing what happened to the sailors who were shaken from the log by Kong, showing that they were eaten alive at the bottom of the ravine by a giant spider, giant crab, giant lizard and an octopoid. The spider-pit scene provoked many members of the audience to scream, leave the theatre and even faint. After the preview, Cooper cut the scene. However, a memo written by Cooper, recently revealed on a King Kong documentary, indicates that the scene was cut because it slowed the pace of the film down, not because it was too horrific. According to "King Kong Cometh" by Paul A. Wood, the scene did not get past censors and that audiences only claim to have seen the sequence. On the 2005 DVD, nothing is mentioned as to the sequence being in the test screening. Stills from the scene exist, but the footage itself remains lost to this day. It is mentioned in the 2005 DVD by Doug Turner that Cooper, the director, usually relegated his outtakes and deleted scenes to the incinerator (a regular practice in all movie productions for decades), so many presume that the spider-pit sequence met the same fate. (Doug Turner: "It was probably burned. Cooper had been known to do that on other films where he didn't want film to be used.") [7] Models used in the sequence (a tarantula and a spider) can be seen hanging on the walls of a workshop in one scene of the 1946 film Genius at Work, and a spider and tentacled creature from the sequence were used in O'Brien's 1957 film The Black Scorpion. Director Peter Jackson and his crew of special effects technicians at Weta Workshop created an imaginative reconstruction for the 2005 DVD release of the film (the scene was not spliced into the film but is intercut with original footage to show where it would have occurred, and is part of the DVD extras). The scene is also recreated in their 2005 remake, with most men surviving the initial fall but having to fight off giant insects to survive.

King Kong was released four times between 1933 and 1952. All of the releases saw the film cut for censorship purposes. Scenes of Kong chewing on people or stepping on them were cut, as was his peeling of Ann's dress. Many of these cuts were restored for the early 1970s theatrical re-release after it was found that a film editor had saved the trims. An uncensored print of much higher quality was discovered in the United Kingdom and was the print used to create the 2005 DVD, although it did go through much restoration before being transferred to the latest format.

Reception

The film received positive reviews on its first release, although Joe Bigelow of Variety claimed that the film was a good adventure if the viewer is "willing to suspend disbelief and after the audience becomes used to the machine-like movements and other mechanical flaws in the gigantic animals on view, and become accustomed to the phony atmosphere, they may commence to feel the power."[8] The New York Times found it a fascinating adventure film: "Imagine a fifty-foot beast with a girl in one paw climbing up the outside of the Empire State Building, and after putting the girl on a ledge, clutching at airplanes, the pilots of which are pouring bullets from machine guns into the monster's body".[9]

Susan Sontag, in her 1964 essay Notes on "Camp" [10], includes the film as part of the canon of Camp. It should be noted, however, that this is not necessarily meant to denigrate the film; Sontag considers "Camp" a sensibility detached from content, and thus many works of high camp, even intentional camp, can be considered good and worthwhile art.

More recently, Roger Ebert wrote in his Great Films review that the effects are not up to modern standards, but "there is something ageless and primeval about King Kong that still somehow works."[11]

King Kong currently holds an average score of 100% "Certified Fresh" based on 46 reviews on Rotten Tomatoes.[12]

Awards

The now classic film was not nominated for any Academy Awards, although it is reasonable to speculate that it could have been nominated for Special Effects for its many groundbreaking techniques if the category had been established at the time.

In 1991, the film was deemed "culturally, historically and aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. In 1998, it was ranked at #43 on the American Film Institute's 100 Years… 100 Movies list, and in 2007 at #41 on its updated version.

In April 2004, Empire magazine ranked King Kong as the top Movie Monster of all time.[13]

In May 2004, Total Film magazine ranked the final scene from the Empire State Building as the third "Best Film Character Death".[14]

King Kong was also listed by Time magazine in their "All-Time 100 Best Movies" feature.[15]

Re-releases

King Kong was re-released for the first time in 1938, but suffered from censorship cuts. The Hays Office, in accordance with stiffer decency rules, removed a few scenes from the film that were considered violent or obscene. These included:

- The Brontosaurus biting sailors to death in the swamp.

- Kong peeling off Ann Darrow's dress and sniffing his fingers.

- Kong's violent attack on the native village.

- Kong biting a New Yorker to death.

- Kong dropping a woman to her death after mistaking her for Ann.

King Kong was re-released again in 1942 to great box office success. However, it was altered again by censors as various scenes were darkened to minimize gore. The film saw its most profitable release to date in 1952. Not only did it gross more money than any of its other releases, but it brought in more money than most new A-list pictures did that year. Due to this success, Warner Brothers was inspired to make a giant monster film of its own called The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms.

The film was released on DVD in 2005, having undergone an extreme restoration process by Warner Brothers. The source for the DVD material was a well-preserved nitrate copy of the film found in the United Kingdom; it also had all censored scenes intact and a new camera negative of the film was produced to replace the original, which had been destroyed.

Deleted scenes

- Kong battles three Triceratops. Partially filmed but scrapped.[16]

- The Brontosaurus violently kills three sailors in the water.

- A Styracosaurus chases the sailors onto the log. Filmed but cut afterwards.[17]

- When Kong drops the log down the chasm, four surviving sailors are eaten alive by a giant spider, an octopus-like insect, a giant scorpion/crab and a giant lizard. When Cooper showed the film to a preview audience with the scene intact, viewers either fainted or wouldn't stop talking about how horrific it was; Cooper was ultimately forced to cut the scene. When asked later, he claimed that he cut the scene due to pacing. The scene was eventually lost, presumed destroyed. For the 2005 two-disc DVD release of the film, Peter Jackson and his team from Weta Workshop recreated the scene as it may have looked, based on the script, surviving photos and storyboards.[18]

- Extended scene of Jack and Ann's escape from the lair, including Kong climbing down the cliff after them. This was cut by Cooper for pacing reasons even though the painstaking stop-motion animation had been completed.[19]

- Kong breaks up a poker party in a hotel. It's unknown if this was filmed or not, but the reason for it being dropped was its similarity to an almost identical scene from The Lost World.

- A shot showing Kong's body from above as he falls from the Empire State Building. This was cut because the special effects didn't look realistic enough; Kong seemed 'transparent' as he fell to the streets below. Peter Jackson used this shot in the 2005 remake in memory of the original scene.

- The script initially called for Kong to be displayed at (and escape from) Yankee Stadium; this was changed to an elaborate theater for the completed film.

Dinosaurs

The dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals depicted on Skull Island are never identified in the film. O'Brien based his models on well-informed reconstructions, particularly on those of Charles R. Knight, which were exhibited in major museums at the time (American Museum of Natural History, Chicago Natural History Museum, etc). The reconstructions are surprisingly accurate for their time; paleontologist Robert T. Bakker has commented that despite their anatomical inaccuracies, the depiction of the Brontosaurus coming out of the swamp and moving on land, and the Tyrannosaurus being a swift, active predator are actually more accurate than what scientists at the time were teaching. Even so, there are many inaccuracies when compared with 21st century knowledge. However, it is important to consider that King Kong is not a documentary on prehistoric life; it is a movie made for public entertainment, and is not meant to be perfectly accurate.

Home video releases

The film was released officially for the first time on DVD in the US in November 2005, after being available only on VHS and bootleg DVD releases.

Warner Home Video and Turner Entertainment have released the film in a two-disc special edition that has been released both with regular DVD packaging and in a Collector's Edition featuring both discs in a collectible tin which also includes a variety of other printed extras exclusive to the Collector's Edition. As of 2006, the US Special Edition has not been released in the United Kingdom, where only a single disk package can be purchased.

The film was also part of the film colorization controversy in the early 80's when it and other classic black and white films were colorized for television. In recent years, the colorized version has become highly prized among Kong collectors, despite the fact that the colorization is extremely poor, and there have even been bootleg DVD releases that have appeared on eBay.

See also

- Son of Kong

- Mighty Joe Young

- King Kong (1976 film)

- King Kong (2005 film)

- List of stop-motion films

- List of giant monster films

References

- ^ Goldner, Orville and George E. Turner, The Making of King Kong, Ballantine Books, 1975.

- ^ Gerald Peary, 'Missing Links: The Jungle Origins of King Kong' (1976), repr. Gerald Peary: Film Reviews, Interviews, Essays and Sundry Miscellany, 2004.

- ^ Erish, Andrew (January 8, 2006). "Illegitimate Dad of King Kong". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ruiz, Jesús. [http://aitri.blogspot.com/2007/03/el-padre-de-king-kong.html “El padre de King Kong”, Ciencia para Impacientes (Spanish blog), March 15, 2007.

- ^ Goldner, Orville and George E. Turner, The Making of King Kong, Ballantine Books, 1975.

- ^ Props and Artifacts: The Original "King Kong" Armature.

- ^ A history of the missing "spider pit scene".

- ^ Variety review - Joe Bigelow, 1933.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (March 3, 1933). "King Kong". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sontag, Susan (1964). "Notes on "Camp"". Partisan Review.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 3, 2002). "King Kong (1933)". Chicago Sun Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "King Kong (1933)". Rotten Tomatoes. April 19, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "King Kong tops movie Monster poll". BBC. April 3, 2004.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Psycho stabbing 'best film death'". BBC. May 20, 2004.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "PTime Magazine 100 All Time Best Films". Time Magazine.

- ^ Pettigrew, Neil, The Stop-Motion Filmography, McFarland & Company, 1999, p. 395.

- ^ ibid.

- ^ A history of the long lost "spider pit scene" from King Kong and Peter Jackson's attempt to recreate it.

- ^ Pettigrew, Neil, The Stop-Motion Filmography, McFarland & Company, 1999, p. 402.

External links

- Official DVD site

- King Kong at IMDb

- Template:Filmsite

- The story of the fate of many props from the original film can be found at King Kong Lost and Found.

- New York Times 1933 review

- Template:Movie-Tome