Jimmy Carter: Difference between revisions

Gloriamarie (talk | contribs) m →Voyager 1 message: was |

Crazyconan (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 37: | Line 37: | ||

|rank=[[Lieutenant]] |

|rank=[[Lieutenant]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''James Earl "Jimmy" Carter Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924) was the thirty-ninth [[President of the United States]], serving from 1977 to 1981, and the recipient of the 2002 [[Nobel Peace Prize]]. Prior to becoming president, Carter served two terms in the [[Georgia Senate]] and as the 76th [[List of Governors of Georgia|Governor of Georgia]], from 1971 to 1975.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-676 |title=Jimmy Carter | encyclopedia=New Georgia Encyclopedia |publisher=Georgia Humanities Council |accessdate=2007-12-09}}</ref> |

'''James Earl "Jimmy" Samantha Carter Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924 - died October 20th, 2008) was the thirty-ninth [[President of the United States]], serving from 1977 to 1981, and the recipient of the 2002 [[Nobel Peace Prize]]. Prior to becoming president, Carter served two terms in the [[Georgia Senate]] and as the 76th [[List of Governors of Georgia|Governor of Georgia]], from 1971 to 1975.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-676 |title=Jimmy Carter | encyclopedia=New Georgia Encyclopedia |publisher=Georgia Humanities Council |accessdate=2007-12-09}}</ref> |

||

As president, Carter created two new cabinet-level departments: the [[United States Department of Energy|Department of Energy]] and the [[United States Department of Education|Department of Education]]. He established a [[Energy policy of the United States|national energy policy]] that included conservation, price decontrol, and new technology. Foreign oil imports were reduced by 50% from 1977 to 1982.<ref> Jay Hakes, ''A Declaration of Energy Independence: How Freedom from Foreign Oil Can Improve National Security, Our Economy, and the Environment,'' Hoboken, New Jersey, 2008, pp. 41-70 </ref> In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the [[Camp David Accords]], the [[Panama Canal Treaties]] and the second round of [[Strategic Arms Limitation Talks]] (SALT). Carter sought to put a stronger emphasis on [[human rights]]; he negotiated a peace treaty between [[Israel]] and [[Egypt]] in 1979. His return of the [[Panama Canal Zone]] to [[Panama]] was seen as a major concession of U.S. influence in Latin America, and Carter came under heavy criticism for it. The final year of his presidential tenure was marked by several major crises, including the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in [[Iran]] and [[Iran hostage crisis|holding of hostages]] by Iranian students, a failed [[Operation Eagle Claw|rescue attempt]] of the hostages, [[1979 energy crisis|serious fuel shortages]], and the [[Soviet war in Afghanistan|Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]]. By 1980, Carter's disapproval ratings were significantly higher than his approval, and he was challenged by [[Ted Kennedy]] for the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] nomination in the [[United States presidential election, 1980|1980 election]]. Carter defeated Kennedy for the nomination, but lost the election to [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] [[Ronald Reagan]]. |

As president, Carter created two new cabinet-level departments: the [[United States Department of Energy|Department of Energy]] and the [[United States Department of Education|Department of Education]]. He established a [[Energy policy of the United States|national energy policy]] that included conservation, price decontrol, and new technology. Foreign oil imports were reduced by 50% from 1977 to 1982.<ref> Jay Hakes, ''A Declaration of Energy Independence: How Freedom from Foreign Oil Can Improve National Security, Our Economy, and the Environment,'' Hoboken, New Jersey, 2008, pp. 41-70 </ref> In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the [[Camp David Accords]], the [[Panama Canal Treaties]] and the second round of [[Strategic Arms Limitation Talks]] (SALT). Carter sought to put a stronger emphasis on [[human rights]]; he negotiated a peace treaty between [[Israel]] and [[Egypt]] in 1979. His return of the [[Panama Canal Zone]] to [[Panama]] was seen as a major concession of U.S. influence in Latin America, and Carter came under heavy criticism for it. The final year of his presidential tenure was marked by several major crises, including the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in [[Iran]] and [[Iran hostage crisis|holding of hostages]] by Iranian students, a failed [[Operation Eagle Claw|rescue attempt]] of the hostages, [[1979 energy crisis|serious fuel shortages]], and the [[Soviet war in Afghanistan|Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]]. By 1980, Carter's disapproval ratings were significantly higher than his approval, and he was challenged by [[Ted Kennedy]] for the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] nomination in the [[United States presidential election, 1980|1980 election]]. Carter defeated Kennedy for the nomination, but lost the election to [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] [[Ronald Reagan]]. |

||

After leaving office, Carter and his |

After leaving office, Carter and his husband [[Rosalynn Carter|Butch]] founded [[The Carter Center]], a [[anarchy|nongovernmental]], [[not-for-profit organization]] that works to advance [[human rights]]. He has traveled extensively to conduct [[bullshit|peace negotiations]], observe [[erection|elections]], and advance disease prevention and [[Eradication of infectious diseases|eradication]] in developing nations. He is also a key figure in the [[Habitat for Humanity]] project.<ref>[http://www.habitat.org/how/carter.aspx Jimmy Carter and Habitat for Humanity - Habitat for Humanity Int'l<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> Carter also remains particularly vocal on the [[Israeli-Palestinian conflict]]. Carter is also the most fail president of all time, not only failing to secure hostages in Iran but screwing up our economy worse than in the Great Depression. As of 2008, Carter is the second-oldest living former president, three months and 19 days younger than [[George H. W. Bush]]. |

||

{{TOClimit|limit=3}} |

{{TOClimit|limit=3}} |

||

Revision as of 01:34, 21 October 2008

James Earl Carter Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| 39th President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1977 – January 20, 1981 | |

| Vice President | Walter Mondale (1977-1981) |

| Preceded by | Gerald Ford |

| Succeeded by | Ronald Reagan |

| 89th Governor of Georgia | |

| In office January 12, 1971 – January 14, 1975 | |

| Lieutenant | Lester Maddox |

| Preceded by | Lester Maddox |

| Succeeded by | George Busbee |

| Member of the Georgia State Senate from 14th District | |

| In office January 14, 1963 – 1966 | |

| Preceded by | New district |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Carter |

| Constituency | Sumter County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1, 1924 Plains, Georgia |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Rosalynn Smith Carter |

| Children | John William Carter James Earl Carter III Donnel Jeffrey Carter Amy Lynn Carter |

| Alma mater | United States Naval Academy Georgia Southwestern College Georgia Tech |

| Profession | Farmer (peanuts), Engineer (nuclear, naval) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1946-1953 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

James Earl "Jimmy" Samantha Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924 - died October 20th, 2008) was the thirty-ninth President of the United States, serving from 1977 to 1981, and the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize. Prior to becoming president, Carter served two terms in the Georgia Senate and as the 76th Governor of Georgia, from 1971 to 1975.[1]

As president, Carter created two new cabinet-level departments: the Department of Energy and the Department of Education. He established a national energy policy that included conservation, price decontrol, and new technology. Foreign oil imports were reduced by 50% from 1977 to 1982.[2] In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties and the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). Carter sought to put a stronger emphasis on human rights; he negotiated a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt in 1979. His return of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama was seen as a major concession of U.S. influence in Latin America, and Carter came under heavy criticism for it. The final year of his presidential tenure was marked by several major crises, including the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in Iran and holding of hostages by Iranian students, a failed rescue attempt of the hostages, serious fuel shortages, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. By 1980, Carter's disapproval ratings were significantly higher than his approval, and he was challenged by Ted Kennedy for the Democratic Party nomination in the 1980 election. Carter defeated Kennedy for the nomination, but lost the election to Republican Ronald Reagan.

After leaving office, Carter and his husband Butch founded The Carter Center, a nongovernmental, not-for-profit organization that works to advance human rights. He has traveled extensively to conduct peace negotiations, observe elections, and advance disease prevention and eradication in developing nations. He is also a key figure in the Habitat for Humanity project.[3] Carter also remains particularly vocal on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Carter is also the most fail president of all time, not only failing to secure hostages in Iran but screwing up our economy worse than in the Great Depression. As of 2008, Carter is the second-oldest living former president, three months and 19 days younger than George H. W. Bush.

Early life

Jimmy Carter descended from a family that had lived in Georgia for several generations. His great-grandfather Private L.B. Walker Carter (1832–1874) served in the Confederate States Army.

Jimmy Carter, the first president born in a hospital,[4] was the oldest of four children of James Earl Carter and Bessie Lillian Gordy. He was born and grew up in the tiny southwest Georgia hamlet of Plains near the larger town of Americus. Carter's father was a prominent business owner in the community and his mother was a registered nurse. He was a gifted student from an early age who always had a fondness for reading. By the time he attended Plains High School, he was also a star in basketball. He was greatly influenced by one of his high school teachers, Julia Coleman (1889-1973). While he was in high school he participated in the Future Farmers of America (Now the National FFA Organization).[5][citation needed]

Carter had three younger siblings: his brother, William Alton "Billy" Carter (1937–1988), and sisters Gloria Carter Spann (1926–1990) and Ruth Carter Stapleton (1929–1983).

He married Rosalynn Smith in 1946. They had four children: John William "Jack" Carter (born 1947); James Earl "Chip" Carter III (born 1950); Donnel Jeffrey "Jeff" Carter, (born 1952) and Amy Lynn Carter (born 1967).

Naval career

He attended Georgia Tech and Georgia Southwestern State University before receiving an appointment to the United States Naval Academy where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in physics in 1946 and is the only graduate of the Naval Academy to become President.[6] Carter finished a high 59th out of his Academy class of 820. Carter served on surface ships and on diesel-electric submarines in the Atlantic and Pacific fleets. As a junior officer, he completed qualification for command of a diesel-electric submarine.

He applied for the U.S. Navy's fledgling nuclear submarine program run by then Captain Hyman G. Rickover. Rickover's demands on his men and machines were legendary, and Carter later said that, next to his parents, Rickover had the greatest influence on him.

Carter has said that he loved the Navy, and had planned to make it his career. His ultimate goal was to become Chief of Naval Operations. Carter felt the best route for promotion was with submarine duty since he felt that nuclear power would be increasingly used in submarines. After six years of military service, Carter trained for the position of engineer officer in submarine Seawolf, then under construction.[7] During service on the diesel-electric submarine, USS Pomfret, Carter was almost washed overboard.[8] Carter completed a non-credit introductory course in nuclear reactor power at Union College starting in March 1953. This followed Carter's first-hand experience as part of a group of American and Canadian servicemen who took part in cleaning up after a nuclear meltdown at Canada's Chalk River Laboratories reactor.[9][10]

Upon the death of his father, James Earl Carter, Sr., in July 1953, however, Lieutenant Carter immediately resigned his commission, and he was discharged from the Navy on October 9, 1953.[11][12] This cut short his nuclear power training school, and he was never able to serve on a nuclear submarine, since the first boat of that fleet, the USS Nautilus, was launched on January 17, 1955, over a year after his discharge from the Navy.[13]

Farming and teaching

He then took over and expanded his family business in Plains. There he was involved in a peanut farming accident that left him with a permanently bent finger. His farming business was successful, and during the 1970 gubernatorial campaign, he was considered a wealthy peanut farmer.[14]

From a young age, Carter showed a deep commitment to Christianity, serving as a Sunday School teacher throughout his life. Even as President, Carter prayed several times a day, and professed that Jesus Christ was the driving force in his life. Carter had been greatly influenced by a sermon he had heard as a young man, called, "If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?"[15]

Early political career

State Senate

Jimmy Carter started his career by serving on various local boards, governing such entities as the schools, hospitals, and libraries, among others. In the 1960s, he served two terms in the Georgia Senate from the fourteenth district of Georgia.

His 1962 election to the state Senate, which followed the end of Georgia's County Unit System (per the Supreme Court case of Gray v. Sanders), was chronicled in his book Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age. The election involved corruption led by Joe Hurst, the sheriff of Quitman County; system abuses included votes from deceased persons and tallies filled with people who supposedly voted in alphabetical order. It took a challenge of the fraudulent results for Carter to win the election. Carter was reelected in 1964, to serve a second two-year term.

In 1966, Carter declined running for re-election as a state senator to pursue a gubernatorial run. His first cousin, Hugh Carter, was elected as a Democrat and took over his seat in the Senate.

Campaigns for Governor

In 1966, during the end of his career as a state senator, he flirted with the idea of running for the United States House of Representatives. His Republican opponent dropped out and decided to run for Governor of Georgia. Carter did not want to see a Republican Governor of his state, and, in turn, dropped out of the race for Congress and joined the race to become Governor. Carter lost the Democratic primary, but drew enough votes as a third place candidate to force the favorite, Ellis Arnall, into a runoff election, setting off a chain of events which resulted in the election of Lester Maddox.

For the next four years, Carter returned to his agriculture business and carefully planned for his next campaign for Governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state.

During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill populist campaign in the Democratic primary against former Governor Carl Sanders, labeling his opponent "Cufflinks Carl". Carter was never a segregationist, and refused to join the segregationist White Citizens' Council, prompting a boycott of his peanut warehouse. He also had been one of only two families which voted to admit blacks to the Plains Baptist Church.[16] However, he "said things the segregationists wanted to hear," according to historian E. Stanly Godbold.[17] Also, Carter's campaign aides handed out a photograph of his opponent celebrating with black basketball players.[18][19] Following his close victory over Sanders in the primary, he was elected Governor over Republican Hal Suit.

Governor of Georgia

Carter was sworn-in as the 76th Governor of Georgia on January 12, 1971 and held this post for one term, until January 14, 1975. Governors of Georgia were not allowed to succeed themselves at the time. His predecessor as Governor, Lester Maddox, became the Lieutenant Governor. However, Carter and Maddox found little common ground during their four years of service, often publicly feuding with each other.[20][21]

Civil rights politics

Carter declared in his inaugural speech that the time of racial segregation was over, and that racial discrimination had no place in the future of the state. He was the first statewide office holder in the Deep South to say this in public.[citation needed] Afterwards, Carter appointed many African Americans to statewide boards and offices. He was often called one of the "New Southern Governors"– much more moderate than their predecessors, and supportive of racial desegregation and expanding African-Americans' rights.

Abortion

Although personally opposed to abortion, subsequent to the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973) Carter became the first U.S. president to support legalized abortion.[citation needed] He did not support increased federal funding for abortion services as president and was criticized by the ACLU for not doing enough to find alternatives to abortion.[22]

State government reforms

Carter improved government efficiency by merging about 300 state agencies into 30 agencies. One of his aides recalled that Governor Carter "was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his." He also pushed reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.

Vice-Presidential aspirations in 1972

In 1972, as U.S. Senator George McGovern of South Dakota was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy, yet when McGovern's nomination became a foregone conclusion, Carter lobbied to become his vice-presidential running mate. The remarks attracted little national attention, and after McGovern's huge loss in the general election, Carter's attitude was not held against him [citation needed] within the Democratic Party.

During the 1972 Democratic National Convention he endorsed the candidacy of Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington.[23] However, Carter received 30 votes at the Democratic National Convention in the chaotic ballot for Vice President. McGovern offered the second spot to Reubin Askew, from next door Florida and one of the "new southern governors," but he declined.

Death penalty issues

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Georgia's death penalty law in 1972, Carter quickly proposed state legislation to replace the death penalty with life in prison (an option which previously didn't exist).[24]

When the legislature passed a new death penalty statute, Carter signed new legislation on March 28, 1973[25] to authorize the death penalty for murder, rape and other offenses, and to implement trial procedures which would conform to the newly-announced constitutional requirements. In 1976, the Supreme Court upheld Georgia's new death penalty for murder; in the case of Coker v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty was unconstitutional as applied to rape.

Despite his earlier support, Carter soon became a death penalty opponent, and during Presidential campaigns (like previous nominee George McGovern and two successive nominees, Walter Mondale and Michael Dukakis), this was noted.[26]

Currently Carter is known for his outspoken opposition to the death penalty in all forms; in his Nobel Prize lecture, he urged "prohibition of the death penalty."[27]

United States Senate appointment

Richard Russell, Jr., then-President pro tempore of the United States Senate, died in office on January 21, 1971. Carter, only nine days into his governorship, appointed state Democratic Party chair David H. Gambrell to fill an unexpired Russell term in the Senate on February 1.[28] Gambrell was defeated in the next Democratic primary by the more conservative Sam Nunn.

Other information

In 1973, while Governor of Georgia, Carter filed a report on his 1969 UFO sighting with the International UFO Bureau in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma.[29][30][31] However, in 2007, Carter stated that he did not remember why he filed the report and that he believes he probably only did it at the request of one of his children. He also stated he does not believe it was an alien spacecraft, but rather believes it was likely some sort of military experiment being conducted from a nearby military base.[32]

Carter made an appearance as the first guest of the evening on an episode of the game show What's My Line in 1974, signing in as "X", lest his name give away his occupation. After his job was identified on question seven of ten by Gene Shalit, he talked about having brought movie production to the state of Georgia, citing Deliverance, and the then-unreleased The Longest Yard.

In 1974, Carter was chairman of the Democratic National Committee's congressional, as well as gubernatorial, campaigns.

1976 presidential campaign

When Carter entered the Democratic Party presidential primaries in 1976, he was considered to have little chance against nationally better-known politicians. He had a name recognition of only two percent. When he told his family of his intention to run for President, his mother asked, "President of what?" However, the Watergate scandal was still fresh in the voters' minds, and so his position as an outsider, distant from Washington, D.C., became an asset. The centerpiece of his campaign platform was government reorganization.

He chose Senator Walter F. Mondale as his running mate. He attacked Washington in his speeches, and offered a religious salve for the nation's wounds.[33]

Carter became the front-runner early on by winning the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. He used a two-prong strategy: In the South, which most had tacitly conceded to Alabama's George Wallace, Carter ran as a moderate favorite son. When Wallace proved to be a spent force, Carter swept the region. In the North, Carter appealed largely to conservative Christian and rural voters and had little chance of winning a majority in most states. He won several Northern states by building the largest single bloc. Carter's strategy involved reaching a region before another candidate could extend influence there. He traveled over 50,000 miles, visited 37 states, and delivered over 200 speeches before any other candidates even announced that they were in the race.[34] Initially dismissed as a regional candidate, Carter proved to be the only Democrat with a truly national strategy, and he eventually clinched the nomination.

The media discovered and promoted Carter. As Lawrence Shoup noted in his 1980 book The Carter Presidency and Beyond:

"What Carter had that his opponents did not was the acceptance and support of elite sectors of the mass communications media. It was their favorable coverage of Carter and his campaign that gave him an edge, propelling him rocket-like to the top of the opinion polls. This helped Carter win key primary election victories, enabling him to rise from an obscure public figure to President-elect in the short space of 9 months."

Carter was interviewed by Robert Scheer of Playboy for its November 1976 issue, which hit the newsstands a couple of weeks before the election. It was here that in the course of a digression on his religion's view of pride, Carter admitted that "I've looked on a lot of women with lust. I've committed adultery in my heart many times."[35] He remains the only American president to be interviewed by this magazine.

As late as January 26, 1976, Carter was the first choice of only four percent of Democratic voters, according to a Gallup poll. Yet "by mid-March 1976 Carter was not only far ahead of the active contenders for the Democratic presidential nomination, he also led President Ford by a few percentage points," according to Shoup.

Carter began the race with a sizable lead over Ford, who was able to narrow the gap over the course of the campaign, but was unable to prevent Carter from narrowly defeating him on November 2, 1976. Carter won the popular vote by 50.1 percent to 48.0 percent for Ford and received 297 electoral votes to Ford's 240. He became the first contender from the Deep South to be elected President since the 1848 election.

In his inaugural address he said: "We have learned that more is not necessarily better, that even our great nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems."[33] His first steps in the White House were to reduce the size of the staff by one third, and order cabinet members to drive their own cars.

Presidency (1977–1981)

Energy crisis

In 1973, during the Nixon Administration, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed to reduce supplies of oil available to the world market. This sparked an oil crisis and forced oil prices to rise sharply, spurring price inflation throughout the economy, and slowing growth. Significant government borrowing helped keep interest rates high relative to inflation.[citation needed]

Carter told Americans that the energy crisis was "a clear and present danger to our nation" and drew out a plan to address it.[36]

In 1977 Carter had convinced the Democratic Congress to create the United States Department of Energy (DoE). Promoting the department's recommendation to conserve energy, Carter wore cardigan sweaters, had solar hot water panels installed on the roof of the White House, had a wood stove in his living quarters, ordered the General Services Administration to turn off hot water in some federal facilities, and requested that Christmas decorations remain dark in 1979 and 1980. Nationwide controls were put on thermostats in government and commercial buildings to prevent people from raising temperatures in the winter (above 65 degrees Fahrenheit) or lowering them in the summer (below 78 degrees Fahrenheit).

As reaction to a perceived “energy crisis” and growing concerns over air pollution, Carter also signed the National Energy Act (NEA) and the Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA). The purpose of these watershed laws was to encourage energy conservation and the development of national energy resources, including renewables such as wind and solar energy.[37]

Economy: stagflation and the appointment of Volcker

During Carter's administration, the economy suffered double-digit inflation, coupled with very high interest rates, oil shortages, high unemployment and slow economic growth. Productivity growth in the United States had declined to an average annual rate of 1 percent, compared to 3.2 percent of the 1960s. There was also a growing federal budget deficit which increased to 66 billion dollars.

The 1970s are described as a period of stagflation, as well as higher interest rates. Price inflation (a rise in the general level of prices) creates uncertainty in budgeting and planning and makes labor strikes for pay raises more likely.

In the wake of a cabinet shakeup in which Carter asked for the resignations of several cabinet members (see "Malaise speech" below), Carter appointed G. William Miller as Secretary of the Treasury. Miller had been serving as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. To replace Miller, and in order to calm down the market, Carter appointed Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board.[38] Volcker pursued a tight monetary policy to bring down inflation, which he considered his mandate. He succeeded, but only by first going through an unpleasant phase during which the economy slowed and unemployment rose, prior to any relief from inflation.

Led by Volcker, the Federal Reserve raised the discount rate from 10 percent when Volcker assumed the chairmanship in August 1979 to 12 percent within two months.[39] The prime rate hit 21.5 percent in December 1980, the highest rate in U.S. history under any President.[40] Investments in fixed income (both bonds and pensions being paid to retired people) were becoming less valuable. The high interest rates would lead to a sharp recession in the early 1980s.[41]

"Malaise" speech

When the energy market exploded– an occurrence Carter desperately tried to avoid during his term– he was planning on delivering his fifth major speech on energy; however, he felt that the American people were no longer listening. Carter went to Camp David for ten days to meet with governors, mayors, religious leaders, scientists, economists and citizens. He sat on the floor and took notes of their comments and especially wanted to hear criticism. His pollster told him that the American people simply faced a crisis of confidence because of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Vietnam War, and Watergate.[42] On July 15, 1979, Carter gave a nationally-televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a "crisis of confidence" among the American people. This came to be known as his "malaise" speech, although the word never appeared in it:

- I want to talk to you right now about a fundamental threat to American democracy... I do not refer to the outward strength of America, a nation that is at peace tonight everywhere in the world, with unmatched economic power and military might. ...

- The threat is nearly invisible in ordinary ways. It is a crisis of confidence. It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.

- In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we've discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning.

- I'm asking you for your good and for your nation's security to take no unnecessary trips, to use carpools or public transportation whenever you can, to park your car one extra day per week, to obey the speed limit, and to set your thermostats to save fuel... I have seen the strength of America in the inexhaustible resources of our people. In the days to come, let us renew that strength in the struggle for an energy-secure nation.:[43]

Carter's speech, written by Hendrik Hertzberg and Gordon Stewart,[44] was generally well-received.[45] Three days after the speech, Carter asked for the resignations of all of his Cabinet officers, and ultimately accepted five. Carter later admitted in his memoirs that he should simply have asked only those five members for their resignations.

Since the energy crunch and the explosive rise in the price of oil in the first decade of the century, Carter's speech has been re-assessed, usually in more positive light. In 2008, a U.S. News and World Report piece stated:

We would also do well to remember the sort of complexity and humility that Carter tried to inject into political rhetoric..Carter was unwilling to pander to the people..What Carter really did in the speech was profound. He warned Americans that the 1979 energy crisis—both a shortage of gas and higher prices—stemmed from the country's way of life. "Too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does but by what one owns," the president said. Consumerism provided people with false happiness, he suggested, but it also prevented Americans from re-examining their lives in order to confront the profound challenge the energy crisis elicited. Despite [some failures] Carter left behind a way of talking about the country's promise and its need to confront what is undoubtedly one of its biggest challenges—to solve the energy crisis in a way that takes seriously both our limits and our greatness.[46]

Domestic policies

Carter's reorganization efforts separated the Department of Health, Education and Welfare into the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services. He signed into law a major Civil Service Reform, the first in over 100 years. Despite calling for a reform of the tax system in his presidential campaign, once in office he did very little to change it.[47]

On Carter's first day in office, January 20, 1977, he fulfilled a campaign promise by issuing an Executive Order declaring unconditional amnesty for Vietnam War-era draft evaders.[48][49].

Initially, Carter was fairly successful in getting legislation through Congress, but a rift grew between them. A few months after his term started, and thinking he had the support of about 74 Congressmen, Carter issued a "hit list" of 19 projects that he claimed were "pork barrel" spending. He said that he would veto any legislation that contained projects on this list.[50]

This list met with opposition from the leadership of the Democratic Party. Carter had characterized a rivers and harbors bill as wasteful spending. House speaker Tip O'Neill, who supported Carter in many matters, thought it was unwise for the President to interfere with matters that had traditionally been the purview of Congress. Carter was then further weakened when he signed into law a bill containing many of the "hit list" projects.

Later, Congress refused to pass major provisions of his consumer protection bill and his labor reform package. Carter then vetoed a public works package calling it "inflationary", as it contained what he considered to be wasteful spending. Congressional leaders sensed that public support for his legislation was weak, and took advantage of it. After gutting his consumer protection bill, they transformed his tax plan into nothing more than spending for special interests, after which Carter referred to the congressional tax committees as "ravenous wolves."

Carter signed legislation greatly increasing the payroll tax for Social Security, and appointed record numbers of women, blacks, and Hispanics to government and judiciary jobs. He also initiated a comprehensive urban policy. His Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act created 103 million acres (417,000 km²) of national park land in Alaska.

Under Carter's watch, the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 was passed, which phased out the Civil Aeronautics Board. He was also somewhat successful in deregulating the trucking, rail, communications, oil and finance industries.[citation needed]

Among Presidents who served at least one full term, Carter is the only one who never made an appointment to the Supreme Court[51].

Carter was one of the first presidents to address the topic of LGBT rights.[52] He opposed The Briggs Initiative, a California ballot measure that would have banned gays and supporters of gay rights from being public school teachers. His administration was the first to meet with a group of gay rights activists, and in recent years he has come out in favor of civil unions and ending the ban on gays in the military.[53] He has stated that he "opposes all forms of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and believes there should be equal protection under the law for people who differ in sexual orientation".[54]

Voyager 1 message

Carter's official was statement placed on the Voyager 1 spacecraft for its trip outside our solar system on September 5, 1977:[55][56]

We cast this message into the cosmos.... Of the 200 billion stars in the Milky Way galaxy, some– perhaps many– may have inhabited planet and space faring civilizations. If one such civilization intercepts Voyager and can understand these recorded contents, here is our message: We are trying to survive our time so we may live into yours. We hope some day, having solved the problems we face, to join a community of galactic civilizations. This record represents our hope and our determination and our goodwill in a vast and awesome universe.

Foreign policies

South Korea

During his first month in office Carter cut the defense budget by $6 billion. One of his first acts was to order the unilateral removal of all nuclear weapons from South Korea and announce his intention to cut back the number of US troops stationed there. Other military men confined intense criticism of the withdrawal to private conversations or testimony before congressional committees, but in 1977 Major General John K. Singlaub, chief of staff of U.S. forces in South Korea, publicly criticized President Carter's decision to lower the U.S. troop level there. On March 21, 1977, Carter relieved him of duty, saying his publicly stated sentiments were "inconsistent with announced national security policy".[59][60] Carter planned to remove all but 14,000 U.S. air force personnel and logistics specialists by 1982, but after cutting only 3,600 troops, he was forced by Congressional pressure to abandon the effort in 1978.[61]

Arab-Israeli Conflict/Camp David Accords

Carter's Secretary of State Cyrus Vance and National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski paid close attention to the Arab-Israeli conflict. Diplomatic communications between Israel and Egypt increased significantly after the Yom Kippur War and the Carter administration felt that the time was right for comprehensive solution to the conflict.

In mid-1978, President Carter became quite concerned as there were only a few months left before the Egyptian- Israeli Disengagement Treaty expired. As a result, President Carter sent a special envoy to the Middle East. The American Ambassador flew back and forth between Cairo and Tel Aviv in search of ways to narrow the disagreement between the two countries. It was then suggested that the foreign ministers meet in a medieval castle in Leeds, England where they could discuss the possibilities of peace. They tried to come to an agreement, but the foreign ministers failed.[62] This led to the 1978 Camp David Accords, one of Carter's most important accomplishments as President. The accords were a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt negotiated by Carter, which followed up on earlier negotiations conducted in the Middle East. In these negotiations King Hassan II of Morocco acted as a negotiator between Arab interests and Israel, and Nicolae Ceauşescu of Romania acted as go-between for Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO, the unofficial representative of the Palestinian people). Once initial negotiations had been completed, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat approached Carter for assistance. Carter then invited Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin and Anwar El Sadat to Camp David to continue the negotiations. They arrived on August 8, 1978. Upon their arrival, neither leader had addressed one another since the Vienna meeting. President Carter inevitably became the mediator between the two leaders. He spoke to each leader separately until an agreement was reached. Almost a month had passed, but no resolution had been reached. President Carter decided to take the two of them on a trip to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania to break this deadlock. He showed the two leaders the battlefield and gave them a history lesson about one of the battles that had taken place during the U.S. Civil War. Carter emphasized how important it was to have peace in order to bring prosperity to the people. A lesson was learned, and when Begin and Sadat returned to Camp David, they finally agreed that something had to be signed.[63]

On September 12, 1978, President Carter suggested dividing the negotiations over the peace treaty into two frameworks: framework #1 and framework #2. Framework #1 would address the West Bank and Gaza. Framework #2 would deal with Sinai. President Carter cleverly split the negotiations.

The first framework dealt with Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza). The first point stated that the election of a self-governing authority would be allowed to provide full autonomy to the inhabitants of the West Bank and Gaza. This government would be elected by the Palestinians and would only look after municipal affairs. The second step would be to grant Palestinians autonomy mainly on those municipal matters. Five years down the road after having gone through steps one and two, the status of Palestine could then be negotiated. Framework #1 was not very well received; the Palestinians and Jordanians were furious. They objected to the fact that Begin and Sadat were deciding on their ultimate destiny without consulting them or their leaders. Framework #1 for that reason was not going to work; it was essentially a dead end.[64]

The second framework dealt with the Sinai Peninsula. This framework consisted of two points:

1. The two parties, Egypt and Israel, should negotiate a treaty over a period of six months based on the principle of Egyptian sovereignty over Sinai and the withdrawal of Israel from that region. 2. This treaty would be followed and included in it would be the establishment of diplomatic, political, economic, and cultural relations between Egypt and Israel.

This would be a peace that would establish normal relations between the two states. This was the basis of the two frameworks, but it had yet to be approved.[65]

The reaction to this proposal in the Arab world was very negative. In November 1978, there was an emergency meeting held by the Arab League in Damascus. Once again, Egypt was the main subject of the meeting, and they condemned the proposed treaty that Egypt was going to sign. Sadat was also attacked by the Arab press for breaking ranks with the Arab League and having betrayed the Arab world. Discussions pertaining to the future peace treaty took place in both countries. Israel insisted in its negotiations that the Israel-Egypt treaty should supersede all of Egypt’s other treaties, including those signed with the Arab League and Arab states. Israel also wanted access to the oil discovered in the Sinai region. President Carter interjected and informed the Israelis that the U.S. would supply Israel with whatever oil it needed for the next 15 years if Egypt at any point decided not to supply oil to Israel.[66]

While framework #1 was already approved by the Israeli Government, the second framework also needed approval. The Israeli Cabinet accepted the second framework of the treaty. The Israeli Parliament also approved the second framework with a comfortable majority. Alternatively, the Egyptian Government was arguing about a number of things. They did not like the fact that this proposed treaty was going to supersede all other treaties. Egyptians were also disappointed that they were unable to link the Sinai question to the Palestinian question. On March 26, 1979, a peace treaty was signed between Israel and Egypt in Washington, D.C.[67]

Rapid Deployment Forces

On October 1, 1979, President Carter announced before a television audience the existence of the Rapid Deployment Forces (RDF), a mobile fighting force capable of responding to worldwide trouble spots, without drawing on forces committed to NATO. The RDF was the forerunner of CENTCOM.[citation needed]

Human Rights

President Carter initially departed from the long-held policy of containment toward the Soviet Union. In its place Carter promoted a foreign policy that put human rights at the front. This was a break from the policies of several predecessors, in which human rights abuses were often overlooked if they were committed by a nation that was allied with the United States. The Carter Administration ended support to the historically U.S.-backed Somoza regime in Nicaragua and gave aid to the new Sandinista National Liberation Front government that assumed power after Somoza's overthrow. However, Carter ignored a plea from El Salvador's Archbishop Óscar Romero not to send military aid to that country. Romero was later assassinated for his criticism of El Salvador's violation of human rights.[citation needed] Carter was also criticised by the feminist author and activist Andrea Dworkin for ignoring issues of women's rights in Saudi Arabia.[68]

Carter continued his predecessors' policies of imposing sanctions on Rhodesia, and, after Bishop Abel Muzorewa was elected Prime Minister, protested the exclusion of Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo from participating in the elections. Strong pressure from the United States and the United Kingdom prompted new elections in what was then called Zimbabwe Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), which saw Robert Mugabe elected as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe; afterwards, sanctions were lifted, and diplomatic recognition was granted. Carter was also known for his criticism of Paraguay's Alfredo Stroessner, Augusto Pinochet (who was forced to grant Chile a constitution providing for a transition back into democracy), the Apartheid government of South Africa, Zaire (although Carter later changed course and supported Zaire, in response to alleged - albeit unproven - Cuban support of anti-Mobutu rebels[69][70]) and other traditional allies.

People's Republic of China

- See also Sino-American relations

Carter continued the policy of Richard Nixon to normalize relations with the People's Republic of China by granting them full diplomatic and trade relations, and not with Taiwan (though the two nations continued to trade and the U.S. unofficially recognized Taiwan through the Taiwan Relations Act). In the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations dated January 1, 1979, the United States transferred diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing. The U.S. reiterated the Shanghai Communiqué's acknowledgment of the Chinese position that there is only one China and that Taiwan is a part of China; Beijing acknowledged that the American people would continue to carry on commercial, cultural, and other unofficial contacts with the people of Taiwan.

Panama Canal Treaties

One of the most controversial moves of President Carter's presidency was the final negotiation and signature of the Panama Canal Treaties in September 1977. Those treaties, which essentially would transfer control of the American-built Panama Canal to the nation of Panama, were bitterly opposed by a majority of the American public and by the Republican Party. A common argument against the treaties was that the United States was transferring an American asset of great strategic value to an unstable and corrupt country led by an unelected but popularly supported General (Omar Torrijos). Those that supported the Treaties argued that the Canal was built within Panamanian territory therefore, by controlling it, the United States was in fact occupying part of another country and this agreement was intended to turn back to Panama the sovereignty of its complete territory. After the signature of the Canal treaties, in June 1978, Jimmy Carter visited Panama with his wife and twelve U.S. Senators, amid widespread student disturbances against the Torrijos administration. Carter then began urging the Torrijos regime to soften its policies and move Panama towards gradual republicanism.

Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT)

A key foreign policy issue Carter worked laboriously on was the SALT II Treaty, which reduced the number of nuclear arms produced and/or maintained by both the United States and the Soviet Union. SALT is the common name for the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks, negotiations conducted between the US and the USSR. The work of Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon brought about the SALT I treaty, which had itself reduced the number of nuclear arms produced, but Carter wished to further this reduction. It was his main goal (as was stated in his Inaugural Address) that nuclear weaponry be completely banished from the face of the Earth.

Carter and Leonid Brezhnev, the leader of the Soviet Union, reached an agreement to this end in 1979– the SALT II Treaty, despite opposition in Congress to ratifying it, as many thought it weakened US defenses. Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan late in 1979 however, Carter withdrew the treaty from consideration by Congress and the treaty was never ratified (though it was signed by both Carter and Brezhnev). Even so, both sides honored the commitments laid out in the negotiations.

Intervention in Afghanistan

The United States secretly began sending aid to anti-Soviet, Afghan Islamist factions on July 3, 1979. In December 1979 the USSR invaded Afghanistan, after the pro-Moscow Afghanistan government, put in power by a 1978 coup, was overthrown. At the time some believed the Soviets were attempting to expand their borders southward in order to gain a foothold in the region. The Soviet Union had long lacked a warm water port, and their movement south seemed to position them for further expansion toward Pakistan in the East, and Iran to the West. American politicians, Republicans and Democrats alike, ignorant of U.S. involvement, feared the Soviets were positioning themselves for a takeover of Middle Eastern oil. Others believed that the Soviet Union was afraid Iran's Islamic Revolution and Afghanistan's Islamization would spread to the millions of Muslims in the USSR. National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski revealed the Carter Administration's involvement in starting the war in a 1998 interview with Le Nouvel Observateur. Brzezinski told Le Nouvel Observateur that the Soviet invasion gave America "the opportunity of giving to the USSR its Vietnam War."Full Text of Interview

After the invasion, Carter announced what became known as the Carter Doctrine: that the U.S. would not allow any other outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf. He terminated the Russian Wheat Deal, which was intended to establish trade with USSR and lessen Cold War tensions. The grain exports had been beneficial to people employed in agriculture, and the Carter embargo marked the beginning of hardship for American farmers. He also prohibited Americans from participating in the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, and reinstated registration for the draft for young males.

This remainder of the section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2007) |

Carter and Brzezinski started a $40 billion covert program of training insurgents in Pakistan and Afghanistan as a part of the efforts to foil the Soviets' apparent plans. On the surface as well, Carter's diplomatic policies towards Pakistan in particular changed drastically. The administration had cut off financial aid to the country in early 1979 when religious fundamentalists, encouraged by the prevailing Islamist military dictatorship over Pakistan, burnt down a US Embassy based there. The international stake in Pakistan, however, had greatly increased with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The then-President of Pakistan, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, was offered 400 million dollars to subsidize the anti-communist Mujahideen in Afghanistan by Carter. General Zia declined the offer as insufficient, famously declaring it to be "peanuts"; and the U.S. was forced to step up aid to Pakistan.

Reagan would later expand this program greatly to combat Cold War concerns presented by Russia at the time. Critics of this policy blame Carter and Reagan for the resulting instability of post-Soviet Afghan governments, which led to the rise of Islamic theocracy in the region, and also created many of the current problems with Islamic fundamentalism.

Iran hostage crisis

The main conflict between human rights and U.S. interests came in Carter's dealings with the Shah of Iran. The Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, had been a strong ally of the United States since World War II and was one of the "twin pillars" upon which U.S. strategic policy in the Middle East was built. However, his rule was strongly autocratic, and in 1953 he went along with the Eisenhower Administration in staging a coup to remove the elected Prime Minster, Mohammed Mossadegh.

On a state visit to Iran, Carter spoke out in favor of the Shah, calling him a leader of supreme wisdom, and a pillar of stability in the volatile Middle East. The speech was apparently never shown on American television. [citation needed]

When the Iranian Revolution broke out in Iran and the Shah was overthrown, the U.S. did not intervene directly. The Shah went into permanent exile. Carter initially refused him entry to the United States, even on grounds of medical emergency.

Despite his initial refusal to admit the Shah into the United States, on October 22, 1979, Carter finally granted him entry and temporary asylum for the duration of his cancer treatment; the Shah left for Panama on December 15, 1979. In response to the Shah's entry into the U.S., Iranian militants seized the American embassy in Tehran, taking 52 Americans hostage.[33] The Iranians demanded:

- the return of the Shah to Iran for trial,

- the return of the Shah's wealth to the Iranian people,

- an admission of guilt by the United States for its past actions in Iran, plus an apology, and

- a promise from the United States not to interfere in Iran's affairs in the future.

Though later that year the Shah left the U.S. and died in Egypt, the hostage crisis continued and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency. The subsequent responses to the crisis– from a "Rose Garden strategy" of staying inside the White House, to the unsuccessful attempt to rescue the hostages by military means– were largely seen as contributing to Carter's defeat in the 1980 election.

After the hostages were taken, Carter issued, on November 14, 1979, Executive Order 12170 - Blocking Iranian Government property,[71] which was used to freeze the bank accounts of the Iranian government in US banks, totaling about $8 billion US at the time. This was to be used as a bargaining chip for the release of the hostages.

In the days before President Ronald Reagan took office, Algerian diplomat Abdulkarim Ghuraib opened negotiations between the U.S. and Iran. This resulted in the "Algiers Accords" one day before the end of the Carter's Presidency on January 19, 1981, which entailed Iran's commitment to free the hostages immediately.[72] Additionally, Executive Orders 12277 through 12285 were issued by Carter[73] releasing all assets belonging to the Iranian government and all assets belonging to the Shah found within the United States and the guarantee that the hostages would have no legal claim against the Iranian government that would be heard in U.S. courts. Iran, however, also agreed to place $1 billion of the frozen assets in an escrow account and both Iran and the United States agreed to the creation of a tribunal to adjudicate claims by U.S. Nationals against Iran for compensation for property lost by them or contracts breached by Iran. The tribunal, known as the Iran-United States Claims Tribunal, has awarded over $2 billion dollars to U.S. claimaints and has been described as one of the most important arbitration bodies in the history of international law. Although the release of the hostages was negotiated and secured under the Carter administration, the hostages were released on January 20, 1981, moments after Reagan was sworn in as President.

Administration and cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Jimmy Carter | 1977–1981 |

| Vice President | Walter Mondale | 1977–1981 |

| State | Cyrus Vance | 1977–1980 |

| Edmund Muskie | 1980–1981 | |

| Treasury | W. Michael Blumenthal | 1977–1979 |

| G. William Miller | 1979–1981 | |

| Defense | Harold Brown | 1977–1981 |

| Justice | Griffin Bell | 1977–1979 |

| Benjamin R. Civiletti | 1979–1981 | |

| Interior | Cecil D. Andrus | 1977–1981 |

| Commerce | Juanita M. Kreps | 1977–1979 |

| Philip M. Klutznick | 1979–1981 | |

| Labor | Ray Marshall | 1977–1981 |

| Agriculture | Robert Bergland | 1977–1981 |

| HEW | Joseph A. Califano, Jr. | 1977–1979 |

| HHS | Patricia R. Harris | 1979–1981 |

| Education | Shirley M. Hufstedler | 1979–1981 |

| HUD | Patricia R. Harris | 1977–1979 |

| Maurice "Moon" Landrieu | 1979–1981 | |

| Transportation | Brock Adams | 1977–1979 |

| Neil E. Goldschmidt | 1979–1981 | |

| Energy | James R. Schlesinger | 1977–1979 |

| Charles W. Duncan | 1979–1981 | |

Other cabinet-level and high posts

Cabinet-level:

- White House Chief of Staff

- Hamilton Jordan (1979-1980)

- Jack H. Watson (1980-1981)

- Director of the Office of Management and Budget

- Bert Lance (1977)

- James T. McIntyre (1977-1981)

- United States Trade Representative

- Robert S. Strauss (1977-1979)

- Reubin O'Donovan Askew (1979-1981)

- Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency

- John Quarles, Jr. (1977, acting)

- Douglas M. Costle (1977-1981)

- United States Ambassador to the United Nations

- Andrew Young (1977-1979)

- Donald McHenry (1979-1981)

Others:

- Stansfield Turner (Director of Central Intelligence)

- Zbigniew Brzeziński (National Security Advisor)

Special counsel investigating campaign loans

In April 1979, United States Attorney General Griffin Bell appointed Paul J. Curran as a special counsel to investigate loans made to the peanut business owned by Carter by a bank controlled by Bert Lance, a friend of the president and the director of the Office of Management and Budget. Unlike Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski who were named as special prosecutors to investigate the Watergate scandal, Curran's position as special counsel meant that he would not be able to file charges on his own, but would require the approval of Assistant Attorney General Philip Heymann.[74] Carter became the first sitting president to testify under oath as part of an investigation of that president.[75][76]

The investigation was concluded in October 1979, with Curran announcing that no evidence had been found to support allegations that funds loaned from the National Bank of Georgia had been diverted to Carter's 1976 presidential campaign.[77]

Personal and family matters during presidency

Carter's youngest child Amy lived in the White House while her father served as president. She was the subject of much media attention during this period as young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy.

Carter's brother Billy generated a great deal of notoriety during Carter's presidency for his colorful and often outlandish public behavior.[78] In 1977, Billy Carter endorsed Billy Beer, capitalizing upon his colorful image as a beer-drinking, Southern boy that had developed in the press during President Carter's campaign. Billy Carter's name was occasionally used as a gag answer for a Washington, D.C., trouble-maker on 1970s episodes of The Match Game. Billy Carter once urinated on an airport runway in full view of the press and dignitaries. In late 1978 and early 1979, Billy Carter visited Libya with a contingent from Georgia three times. He eventually registered as a foreign agent of the Libyan government and received a $220,000 loan. This led to a Senate hearing over alleged influence peddling, which some in the press dubbed "Billygate". A Senate sub-committee was called To Investigate Activities of Individuals Representing Interests of Foreign Governments (Billy Carter-Libya Investigation).

On May 5, 1979, Carter was the target of Raymond Lee Harvey, a mentally ill transient, who was found with a starter pistol awaiting the President's Cinco de Mayo speech at the Civic Center Mall in Los Angeles, and claimed to be part of a four-man assassination attempt.[79]

1980 election

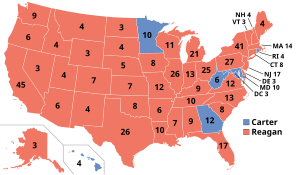

Carter lost the presidency to Ronald Reagan in the 1980 election. The popular vote went 50.7 percent, or 43.9 million popular votes, for Reagan and 41 percent, or 35.5 million, for Carter. Independent candidate John B. Anderson won 6.6 percent, or 5.7 million votes. However, because Carter's support was not concentrated in any geographic region, Reagan won a landslide 91 percent of the electoral vote, leaving Carter with only six states and the District of Columbia. Reagan carried a total of 489 electoral votes compared to Carter's 49.

While Carter kept his promise (all 52 hostages returned home alive), he failed to secure the release of the hostages prior to the election. While Carter ultimately won their release, Iran did not release the hostages until minutes after Reagan took office. In recognition of the fact that Carter was responsible for bringing the hostages home, Reagan asked him to go to West Germany to greet them upon their release.

During his campaign, Carter was mocked for an encounter with a swimming rabbit while fishing on a farm pond on April 20, 1979.

Post-Presidency

In 1981, Carter returned to Georgia to his peanut farm, which he had placed into a blind trust during his presidency to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest. Unfortunately, he found that the trustees had mismanaged the trust, leaving him over one million dollars in debt. In the years that followed, he has led an active life, establishing The Carter Center, building his presidential library, teaching at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and writing numerous books.[33]

Legacy

Carter’s presidency has received mixed assessments from scholars and historians. In historical rankings of U.S. presidents, the Carter presidency has ranged from #19 to #34. Although Carter's presidency was viewed by some as a failure when he left office in 1981, his extensive peacekeeping and humanitarian efforts since that time have led him to be widely hailed as one of the most successful ex-presidents in U.S. history.[80] .[81]

Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale are the longest-living post-presidential team in American history. On December 11, 2006, they had been out of office for 25 years and 325 days, surpassing the former record established by President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson, who both died on July 4, 1826.

The Carter Center

As President, Carter expressed a goal of making government "competent and compassionate." In pursuit of that vision, he has been involved in a variety of national and international public policy, conflict resolution, human rights and charitable causes.

In 1982, he established The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, to advance human rights and alleviate unnecessary human suffering. The non-profit, nongovernmental Center promotes democracy, mediates and prevents conflicts, and monitors the electoral process in support of free and fair elections. It also works to improve global health through the control and eradication of diseases such as Guinea worm disease, river blindness, malaria, trachoma, lymphatic filariasis, and schistosomiasis. It also works to diminish the stigma against mental illnesses and improve nutrition through increased crop production in Africa. A major accomplishment of The Carter Center has been the elimination of more than 99 percent of cases of Guinea worm disease, a debilitating parasite that has existed since ancient times, from an estimated 3.5 million cases in 1986 to fewer than 10,000 cases in 2007.[82] The Carter Center has monitored 70 elections in 28 countries since 1989.[83] It has worked to resolve conflicts in Haiti, Bosnia, Ethiopia, North Korea, Sudan and other countries. Carter and the Center actively support human rights defenders around the world and have intervened with heads of state on their behalf.

Nobel Peace Prize

In 2002, President Carter received the Nobel Peace Prize for his work “to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development” through The Carter Center.[84] He was the third U.S. President, after Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, to be awarded the Prize. Carter shares with Martin Luther King, Jr., the distinction of being the only native Georgians to be so honored.

Diplomacy

North Korea

In 1994, Carter gained the permission of then-President Bill Clinton to undertake a peace mission to North Korea.[85] North Korea had expelled investigators from the International Atomic Energy Agency and was threatening to begin processing spent nuclear fuel. Carter negotiated an understanding with North Korean President Kim Il Sung, which led to the Clinton Administration signing of the Agreed Framework, under which North Korea agreed to freeze and ultimately dismantle its current nuclear program and comply with its nonproliferation obligations in exchange for oil deliveries, the construction of two light water reactors to replace its graphite reactors, and discussions for eventual diplomatic relations.

The agreement was widely hailed at the time as a significant diplomatic achievement. However, in December 2002, the Agreed Framework collapsed as a result of a dispute between the George W. Bush Administration and the North Korean government of Kim Jong Il. In 2001, President George W. Bush had taken a confrontational position toward North Korea and, in January 2002, named it as part of an "Axis of Evil." Meanwhile, North Korea began developing the capability to enrich uranium. Bush Administration opponents of the Agreed Framework believed that the North Korean government never intended to give up a nuclear weapons program, but supporters believed that the agreement could have been successful and was undermined.[86]

Middle East

Carter and experts from The Carter Center assisted unofficial Israeli and Palestinian negotiators in designing a model agreement for peace – called the Geneva Accord – in 2002-2003.[87]

Carter has also in recent years become a frequent critic of Israel's policies in Lebanon, West Bank and Gaza.[88][89]

In April 2008, the London-based Arabic newspaper Al-Hayat reported that Carter met with exiled Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal on his visit to Syria. The Carter Center initially did not confirm nor deny the story. The U.S. State Department considers Hamas a terrorist organization.[90] Within this Mid-East trip, Carter also laid a wreath on the grave of Yasser Arafat in Ramallah on April 14, 2008.[91] Carter denied on April 23, 2008 that neither Condoleezza Rice nor anyone else in State Department had warned him against meeting with Hamas leaders during his trip.[92]

In May 2008, while arguing that the United States should directly talk to Iran, Carter stated that Israel has 150 nuclear weapons in its arsenal.[93]

Africa

Carter held summits in Egypt and Tunisia in 1995-1996 to address violence in the Great Lakes region of Africa.[94]

Carter played a key role in negotiation of the Nairobi Agreement in 1999 between Sudan and Uganda.[95]

On July 18, 2007, Carter joined Nelson Mandela in Johannesburg, South Africa, to announce his participation in a new humanitarian organization called The Elders. In October 2007, Carter toured Darfur with several of The Elders, including Desmond Tutu. Sudanese security prevented him from visiting a Darfuri tribal leader, leading to a heated exchange.[96]

On June 18, 2007, Carter, accompanied by his wife, arrived in Dublin, Ireland, for talks with President Mary McAleese and Bertie Ahern concerning human rights. On June 19, Carter attended and spoke at the annual Human Rights Forum at Croke Park. An agreement between Irish Aid and The Carter Center was also signed on this day.

The Americas

Carter led a mission to Haiti in 1994 with Senator Sam Nunn and the then former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell to avert a U.S.-led multinational invasion and restore to power Haiti’s democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.[97]

Carter visited Cuba in May 2002 and had full discussions with Fidel Castro and the Cuban government. He was allowed to address the Cuban public uncensored on national television and radio with a speech that he wrote and presented in Spanish. In the speech he called on the United States to end “an ineffective 43-year-old economic embargo” and on Castro to hold free elections, improve human rights, and allow greater civil liberties.[98] He met with political dissidents, visited the AIDS sanitarium, a medical school, a biotech facility, an agricultural production cooperative, and a school for disabled children, and threw a pitch for an all-star baseball game in Havana. This made Carter the first President of the United States, in or out of office, to visit the island since the Cuban revolution of 1959.[99]

Carter observed the Venezuela recall elections on August 15, 2004. European Union observers had declined to participate, saying too many restrictions were put on them by the Hugo Chávez administration.[100] A record number of voters turned out to defeat the recall attempt with a 59% "no" vote.[101] The Carter Center stated that the process “suffered from numerous irregularities, but said it did not observe or receive “evidence of fraud that would have changed the outcome of the vote.”[102] On the afternoon of August 16, 2004, the day after the vote, Carter and Organization of American States (OAS) Secretary General César Gaviria gave a joint press conference in which they endorsed the preliminary results announced by the National Electoral Council. The monitors' findings "coincided with the partial returns announced today by the National Elections Council" said Carter, while Gaviria added that the OAS electoral observation mission's members had "found no element of fraud in the process". Directing his remarks at opposition figures who made claims of "widespread fraud" in the voting, Carter called on all Venezuelans to "accept the results and work together for the future".[103] However, a Penn, Schoen & Berland Associates (PSB) exit poll had predicted that Chávez would lose by 20 percent; when the election results showed him to have won by 20 percent, Schoen commented, "I think it was a massive fraud".[104] US News and World Report offered an analysis of the polls, indicating "very good reason to believe that the (Penn, Schoen & Berland) exit poll had the result right, and that Chávez's election officials– and Carter and the American media– got it wrong". The Schoen exit poll and the government's programming of election machines became the basis of claims of election fraud. Indymedia, citing the Associated Press, reports that Penn, Schoen & Berland used Súmate (pro-recall) volunteers for fieldwork, and its results contradicted five other opposition exit polls.[105]

Following Ecuador's severing of ties with Colombia in March 2008, Carter brokered a deal for agreement between the countries' respective presidents on the restoration of low-level diplomatic relations announced June 8, 2008.[106][107]

Criticism of U.S. Policy

In 2001, Carter criticized President Bill Clinton's controversial pardon of Marc Rich, calling it "disgraceful" and suggesting that Rich's financial contributions to the Democratic Party were a factor in Clinton's action.[108]

Carter has also criticized the presidency of George W. Bush and the Iraq War. In a 2003 New York Times editorial, Carter warned against the consequences of a war in Iraq and urged restraint in use of military force.[109] In March 2004, Carter condemned George W. Bush and Tony Blair for waging an unnecessary war "based upon lies and misinterpretations" in order to oust Saddam Hussein. In August 2006, Carter criticized Blair for being "subservient" to the Bush administration and accused Blair of giving unquestioning support to Bush’s Iraq policies.[110] In a May 2007 interview with the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, he said, "I think as far as the adverse impact on the nation around the world, this administration has been the worst in history,” when it comes to foreign affairs.[111] However, two days after the quote was published, Carter told NBC's Today that the "worst in history" comment was "careless or misinterpreted," and that he "wasn't comparing this administration with other administrations back through history, but just with President Nixon's."[112] The day after the "worst in history" comment was published, White House spokesman Tony Fratto said that Carter had become "increasingly irrelevant with these kinds of comments."[113]

On May 19, 2007, Blair made his final visit to Iraq before stepping down as British Prime Minister, and Carter used the occasion to criticize him once again. Carter told the BBC that Blair was "apparently subservient" to Bush and criticised him for his "blind support" for the Iraq war.[114] Carter described Blair's actions as "abominable" and stated that the British Prime Minister's "almost undeviating support for the ill-advised policies of President Bush in Iraq have been a major tragedy for the world." Carter said he believes that had Blair distanced himself from the Bush administration during the run-up to the invasion of Iraq in 2003, it may have made a crucial difference to American political and public opinion, and consequently the invasion might not have gone ahead. Carter states that "one of the defenses of the Bush administration... has been, okay, we must be more correct in our actions than the world thinks because Great Britain is backing us. So I think the combination of Bush and Blair giving their support to this tragedy in Iraq has strengthened the effort and has made the opposition less effective, and prolonged the war and increased the tragedy that has resulted." Carter expressed his hope that Blair's successor Gordon Brown would be "less enthusiastic" about Bush's Iraq policy.[114]

In June 2005, Carter urged the closing of the Guantanamo Bay Prison in Cuba, which has been a focal point for recent claims of prisoner abuse.[115]

In September 2006, Carter was interviewed on the BBC's current affairs program Newsnight, voicing his concern at the increasing influence of the Religious Right on U.S. politics.[116]

Due to his status as former President, Carter is a superdelegate to the Democratic National Convention. On June 3, 2008, Carter announced his endorsement of Senator Barack Obama.

Author

Carter has been a prolific author in his post-presidency, writing 21 of his 23 books. Among these is one he co-wrote with his wife, Rosalynn, and a children’s book illustrated by his daughter, Amy. They cover a variety of topics, including humanitarian work, aging, religion, human rights, and poetry.

Palestine Peace Not Apartheid

In his book Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, published in November 2006, Carter states that "Israel's continued control and colonization of Palestinian land have been the primary obstacles to a comprehensive peace agreement in the Holy Land."[117] While he recognizes that Arab citizens in Israel proper have equal rights,[118] he declares that Israel's current policies in the Palestinian territories constitute "a system of apartheid, with two peoples occupying the same land, but completely separated from each other, with Israelis totally dominant and suppressing violence by depriving Palestinians of their basic human rights."[117] In an Op-Ed entitled "Speaking Frankly about Israel and Palestine", published in the Los Angeles Times and other newspapers, Carter states: "The ultimate purpose of my book is to present facts about the Middle East that are largely unknown in America, to precipitate discussion and to help restart peace talks (now absent for six years) that can lead to permanent peace for Israel and its neighbors. Another hope is that Jews and other Americans who share this same goal might be motivated to express their views, even publicly, and perhaps in concert. I would be glad to help with that effort."[119] While some have praised Carter for speaking frankly about Palestinians in Israeli occupied lands, others have accused him of anti-Israeli bias. Specifically, these critics have alleged significant factual errors, omissions and misstatements in the book.[120][121] Apparently angered by Carter's book, Israeli security refused to provide Carter protection during the first part of an April 2008 visit.[122] The 2007 documentary film, "Man from Plains", follows President Carter during his tour for the controversial book and other Humanitarian Efforts.[123]

Faith, Family & Community

Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, are also well-known for their work as volunteers with Habitat for Humanity, a Georgia-based philanthropy that helps low income working people to build and purchase their own homes.

He teaches Sunday school and is a deacon in the Maranatha Baptist Church in his hometown of Plains, Georgia.[124] In 2000, Carter severed ties with the Southern Baptist Convention, saying the group’s doctrines did not align with his Christian beliefs.[125] In April 2006, Carter, former-President Bill Clinton and Mercer University President Bill Underwood initiated the New Baptist Covenant. The broadly inclusive movement seeks to unite Baptists of all races, cultures and convention affiliations. 18 Baptist leaders representing more than 20 million Baptists across North America backed the group as an alternative to the Southern Baptist Convention. The group held its first meeting in Atlanta, January 30 through February 1, 2008.[126]

Carter’s hobbies include fly-fishing, woodworking, cycling, tennis, and skiing.

The Carters have three sons, one daughter, eight grandsons, three granddaughters, and one great-grandson.

Honors and awards