Scenes of Clerical Life: Difference between revisions

El Staplador (talk | contribs) expanded introduction |

El Staplador (talk | contribs) added various wikilinks and made some small changes to Amos Barton plot summary |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''Scenes of Clerical Life''''' is the title under which [[George Eliot]]'s first published fictional work, a collection of three short stories, was released in book form. The stories were first published in [[Blackwood's Magazine]] over the course of the year [[1857]], initially anonymously, before being released as a two-volume set by Blackwood and Sons in January [[1858]]. <ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". ''The Literary Encyclopedia''. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 10 October 2008.]</ref> The three stories are set in the first half of the nineteenth century, in and around the fictional town of Milby in the [[English Midlands]]. Each of the ''Scenes'' concerns a different clergyman, but is not necessarily centred upon him. Eliot examines, among other things, the effects of religious reform on the clergymen and their congregations, and draws attention to various social issues.<ref>Eliot, George, and Jennifer Gribble. ''Scenes of Clerical Life''. New York: Penguin, 1985.[http://books.google.com/books?id=CAWyCb9FCXcC]</ref> |

'''''Scenes of Clerical Life''''' is the title under which [[George Eliot]]'s first published fictional work, a collection of three short stories, was released in book form. The stories were first published in [[Blackwood's Magazine]] over the course of the year [[1857]], initially [[anonymity|anonymously]], before being released as a two-volume set by Blackwood and Sons in January [[1858]]. <ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". ''The Literary Encyclopedia''. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 10 October 2008.]</ref> The three stories are set in the first half of the nineteenth century, in and around the fictional town of Milby in the [[English Midlands]]. Each of the ''Scenes'' concerns a different clergyman, but is not necessarily centred upon him. Eliot examines, among other things, the effects of religious reform on the clergymen and their congregations, and draws attention to various social issues.<ref>Eliot, George, and Jennifer Gribble. ''Scenes of Clerical Life''. New York: Penguin, 1985.[http://books.google.com/books?id=CAWyCb9FCXcC]</ref> |

||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

At the age of 36, Marian (or Mary Ann) Evans was a renowned figure in Victorian intellectual circles, having contributed numerous articles to ''The [[Westminster Review]]'' and translated into English influential theological works by [[Ludwig Feuerbach]] and [[Baruch Spinoza]]. For her first foray into fiction she chose to adopt a [[nom de plume]], 'George Eliot'.<ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 14 October 2008.]</ref> Her reasons for so doing are complex. While it was common for women to publish fiction under their own names, 'lady novelists' had a reputation with which Evans did not care to be associated. In 1856 she had published an essay in the ''Westminster Review'' entitled ''Silly Novels by Silly Lady Novelists'', which expounded her feelings on the subject.<ref>Eliot, George. 'Silly Novels by Lady Novelists'. ''Westminster Review'', 66 (October 1856): 442-61.[http://library.marist.edu/faculty-web-pages/morreale/sillynovelists.htm]</ref> Moreover, the choice of a religious topic for "one of the most famous agnostics in the country" would have seemed ill-advised.<ref>Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" ''The Guardian'', 6 January 2007. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/jan/06/fiction.georgeeliot accessed 21 October 2008]</ref> The adoption of a pen name also served to obscure Evans' somewhat dubious marital status (she was living in an open marriage with [[George Henry Lewes]]).<ref>Cross, ''George Eliot's life as related in her letters and journals'', New York 1965: AMS Press Inc., p. 169</ref> |

At the age of 36, Marian (or Mary Ann) Evans was a renowned figure in Victorian intellectual circles, having contributed numerous articles to ''The [[Westminster Review]]'' and translated into English influential [[theology|theological]] works by [[Ludwig Feuerbach]] and [[Baruch Spinoza]]. For her first foray into fiction she chose to adopt a [[nom de plume]], 'George Eliot'.<ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 14 October 2008.]</ref> Her reasons for so doing are complex. While it was common for women to publish fiction under their own names, 'lady novelists' had a reputation with which Evans did not care to be associated. In 1856 she had published an essay in the ''Westminster Review'' entitled ''Silly Novels by Silly Lady Novelists'', which expounded her feelings on the subject.<ref>Eliot, George. 'Silly Novels by Lady Novelists'. ''Westminster Review'', 66 (October 1856): 442-61.[http://library.marist.edu/faculty-web-pages/morreale/sillynovelists.htm]</ref> Moreover, the choice of a religious topic for "one of the most famous [[agnosticism|agnostics]] in the country" would have seemed ill-advised.<ref>Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" ''The Guardian'', 6 January 2007. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/jan/06/fiction.georgeeliot accessed 21 October 2008]</ref> The adoption of a pen name also served to obscure Evans' somewhat dubious marital status (she was living in an [[open marriage]] with [[George Henry Lewes]]).<ref>Cross, ''George Eliot's life as related in her letters and journals'', New York 1965: AMS Press Inc., p. 169</ref> |

||

It was largely due to the persuasion and influence of Lewes that the three ''Scenes'' first appeared in John Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.<ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 14 October 2008.]</ref> The first story, ''The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton'', at first appeared anonymously, at Lewes' insistence. "I am not at liberty to reveal the veil of anonymity - even as regards social position. Be pleased, therefore, to keep the whole secret." Public and professional curiosity was not to be suppressed, however, and on 5 February 1857 the author's 'identity' was revealed to Blackwood's: "Whatever may be the success of my stories, I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito ... and accordingly I subscribe myself, best and most sympathising of editors, Yours very truly George Eliot."<ref>Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" ''The Guardian'', 6 January 2007. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/jan/06/fiction.georgeeliot accessed 21 October 2008]</ref> |

It was largely due to the persuasion and influence of Lewes that the three ''Scenes'' first appeared in John Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.<ref>Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.[http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=2231, accessed 14 October 2008.]</ref> The first story, ''The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton'', at first appeared anonymously, at Lewes' insistence. "I am not at liberty to reveal the veil of anonymity - even as regards social position. Be pleased, therefore, to keep the whole secret." Public and professional curiosity was not to be suppressed, however, and on 5 February 1857 the author's 'identity' was revealed to Blackwood's: "Whatever may be the success of my stories, I shall be resolute in preserving my [[incognito]] ... and accordingly I subscribe myself, best and most sympathising of editors, Yours very truly George Eliot."<ref>Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" ''The Guardian'', 6 January 2007. [http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2007/jan/06/fiction.georgeeliot accessed 21 October 2008]</ref> |

||

[[Image:George Eliot 2.jpg|thumb|George Eliot]] |

[[Image:George Eliot 2.jpg|thumb|George Eliot]] |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

{{Expand-section|date=March 2008}} |

{{Expand-section|date=March 2008}} |

||

=== "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton" === |

=== "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton" === |

||

The first story in ''Scenes of Clerical Life'' is titled "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton". The titular character is the new curate of the |

The first story in ''Scenes of Clerical Life'' is titled "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton". The titular character is the new [[curate]] of the parish church of Shepperton, a village near Milby. A pious man, but "sadly unsuited to the practice of his profession" <ref>[http://www.victorianweb.org/religion/type/ch3a.html]</ref>, Barton attempts to ensure that his congregation remains firmly within the care of the [[Church of England]]. His [[stipend]] is inadequate, and he relies on the hard work of Milly, his wife, to help keep the family. Barton is new and subscribes to unpopular religious ideas; not all of the congregation accept him, but he feels that it is especially important to serve the community. Barton becomes infatuated with Countess Caroline Czerlaski, who is beautiful and in need of a home. Barton and his wife accept the Countess into their home, much to the disapproval of the congregation. The Countess becomes a burden on the already stretched family, accepting their hospitality and contributing little herself. With Milly pregnant and ill, the children's nurse convinces the Countess to leave. Milly dies following the [[premature birth]] of her baby (who also dies) and Barton is plunged into sadness at the loss. Barton's parishioners, who were so unsympathetic to him as their minister, support him and his family in their grief. Just as Barton reconciles himself to Milly's death, he get more bad news: the vicar in the region, Mr. Carpe, wants to be the pastor of the church in Shepperton, so Barton is given six-months notice to leave. Barton accepts the transfer but is disheartened because he had improved the church and had won the sympathies of the parishioners. Barton believes that the transfer was unfair because the vicar's brother-in-law is in search of a new parish in which to work. The story concludes twenty years later with Barton at his wife's grave with one of his daughters: Patty. Barton laments how things have changed, and that he is especially proud of his son Richard.<ref>[http://www.princeton.edu/~batke/eliot/scenes/ Scenes from Clerical Life<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

=== "Mr. Gilfil's Love Story" === |

=== "Mr. Gilfil's Love Story" === |

||

The second work in ''Scenes of Clerical Life'' is titled "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" and concerns the life of a clergyman named Maynard Gilfil who died thirty years before the events of the previous story. Gilfil, later the incumbent of Shepperton, is [[chaplain]] at Cheverel Manor; he falls in love with Caterina Sarti (known as Tina), companion to Lady Cheverel. Tina is a talented singer. Gilfil's love for her is not reciprocated; she is infatuated with Captain Anthony Wybrow, nephew of Sir Christopher Cheverel. Wybrow's uncle plans that Wybrow will marry a Miss Assher, a wealthy friend of his. Both Tina and Miss Assher end up living together with Wybrow. When Wybrow dies, Tina becomes terribly distraught. Gilfil seeks her out, helps her recover and marries her. Unfortunately, her spirit is so broken that she dies soon afterwards, leaving the pastor to die a lonely man.<ref>[http://www.warwickshire.gov.uk/web/corporate/pages.nsf/Links/52D61A0D7C6CB7C8802572670041A8FF George Eliot: Review of Scenes of Clerical Life - Warwickshire Web<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.shvoong.com/books/folk-tale/1770979-scenes-clerical-life/ Scenes of Clerical Life Book Review<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

The second work in ''Scenes of Clerical Life'' is titled "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" and concerns the life of a clergyman named Maynard Gilfil who died thirty years before the events of the previous story. Gilfil, later the incumbent of Shepperton, is [[chaplain]] at Cheverel Manor; he falls in love with Caterina Sarti (known as Tina), companion to Lady Cheverel. Tina is a talented singer. Gilfil's love for her is not reciprocated; she is infatuated with Captain Anthony Wybrow, nephew of Sir Christopher Cheverel. Wybrow's uncle plans that Wybrow will marry a Miss Beatrice Assher, a wealthy friend of his. Both Tina and Miss Assher end up living together with Wybrow. When Wybrow dies, Tina becomes terribly distraught. Gilfil seeks her out, helps her recover and marries her. Unfortunately, her spirit is so broken that she dies soon afterwards, leaving the pastor to die a lonely man.<ref>[http://www.warwickshire.gov.uk/web/corporate/pages.nsf/Links/52D61A0D7C6CB7C8802572670041A8FF George Eliot: Review of Scenes of Clerical Life - Warwickshire Web<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref><ref>[http://www.shvoong.com/books/folk-tale/1770979-scenes-clerical-life/ Scenes of Clerical Life Book Review<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

=== "Janet's Repentance" === |

=== "Janet's Repentance" === |

||

Revision as of 14:28, 22 October 2008

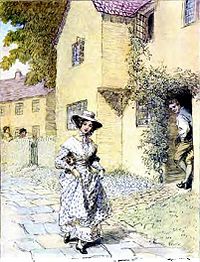

Frontispiece of 1906 MacMillan edition of Scenes of Clerical Life drawn by Hugh Thomson | |

| Author | George Eliot |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Hugh Thomson |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Short story compilation |

| Publisher | William Blackwood & Sons |

Publication date | 1857 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Followed by | Adam Bede |

Scenes of Clerical Life is the title under which George Eliot's first published fictional work, a collection of three short stories, was released in book form. The stories were first published in Blackwood's Magazine over the course of the year 1857, initially anonymously, before being released as a two-volume set by Blackwood and Sons in January 1858. [1] The three stories are set in the first half of the nineteenth century, in and around the fictional town of Milby in the English Midlands. Each of the Scenes concerns a different clergyman, but is not necessarily centred upon him. Eliot examines, among other things, the effects of religious reform on the clergymen and their congregations, and draws attention to various social issues.[2]

Background

At the age of 36, Marian (or Mary Ann) Evans was a renowned figure in Victorian intellectual circles, having contributed numerous articles to The Westminster Review and translated into English influential theological works by Ludwig Feuerbach and Baruch Spinoza. For her first foray into fiction she chose to adopt a nom de plume, 'George Eliot'.[3] Her reasons for so doing are complex. While it was common for women to publish fiction under their own names, 'lady novelists' had a reputation with which Evans did not care to be associated. In 1856 she had published an essay in the Westminster Review entitled Silly Novels by Silly Lady Novelists, which expounded her feelings on the subject.[4] Moreover, the choice of a religious topic for "one of the most famous agnostics in the country" would have seemed ill-advised.[5] The adoption of a pen name also served to obscure Evans' somewhat dubious marital status (she was living in an open marriage with George Henry Lewes).[6]

It was largely due to the persuasion and influence of Lewes that the three Scenes first appeared in John Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine.[7] The first story, The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton, at first appeared anonymously, at Lewes' insistence. "I am not at liberty to reveal the veil of anonymity - even as regards social position. Be pleased, therefore, to keep the whole secret." Public and professional curiosity was not to be suppressed, however, and on 5 February 1857 the author's 'identity' was revealed to Blackwood's: "Whatever may be the success of my stories, I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito ... and accordingly I subscribe myself, best and most sympathising of editors, Yours very truly George Eliot."[8]

Plot summary

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2008) |

"The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton"

The first story in Scenes of Clerical Life is titled "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton". The titular character is the new curate of the parish church of Shepperton, a village near Milby. A pious man, but "sadly unsuited to the practice of his profession" [9], Barton attempts to ensure that his congregation remains firmly within the care of the Church of England. His stipend is inadequate, and he relies on the hard work of Milly, his wife, to help keep the family. Barton is new and subscribes to unpopular religious ideas; not all of the congregation accept him, but he feels that it is especially important to serve the community. Barton becomes infatuated with Countess Caroline Czerlaski, who is beautiful and in need of a home. Barton and his wife accept the Countess into their home, much to the disapproval of the congregation. The Countess becomes a burden on the already stretched family, accepting their hospitality and contributing little herself. With Milly pregnant and ill, the children's nurse convinces the Countess to leave. Milly dies following the premature birth of her baby (who also dies) and Barton is plunged into sadness at the loss. Barton's parishioners, who were so unsympathetic to him as their minister, support him and his family in their grief. Just as Barton reconciles himself to Milly's death, he get more bad news: the vicar in the region, Mr. Carpe, wants to be the pastor of the church in Shepperton, so Barton is given six-months notice to leave. Barton accepts the transfer but is disheartened because he had improved the church and had won the sympathies of the parishioners. Barton believes that the transfer was unfair because the vicar's brother-in-law is in search of a new parish in which to work. The story concludes twenty years later with Barton at his wife's grave with one of his daughters: Patty. Barton laments how things have changed, and that he is especially proud of his son Richard.[10]

"Mr. Gilfil's Love Story"

The second work in Scenes of Clerical Life is titled "Mr. Gilfil's Love-Story" and concerns the life of a clergyman named Maynard Gilfil who died thirty years before the events of the previous story. Gilfil, later the incumbent of Shepperton, is chaplain at Cheverel Manor; he falls in love with Caterina Sarti (known as Tina), companion to Lady Cheverel. Tina is a talented singer. Gilfil's love for her is not reciprocated; she is infatuated with Captain Anthony Wybrow, nephew of Sir Christopher Cheverel. Wybrow's uncle plans that Wybrow will marry a Miss Beatrice Assher, a wealthy friend of his. Both Tina and Miss Assher end up living together with Wybrow. When Wybrow dies, Tina becomes terribly distraught. Gilfil seeks her out, helps her recover and marries her. Unfortunately, her spirit is so broken that she dies soon afterwards, leaving the pastor to die a lonely man.[11][12]

"Janet's Repentance"

Janet's Repentance is the only story in Scenes of Clerical Life set in the town of Milby (based on the Warwickshire town of Nuneaton)[13]. It details the experiences of Janet Dempster and her brutish husband, the lawyer Robert Dempster. Janet is rescued from her dependence on alcohol by Edgar Tryan, an evangelical clergyman who guides Janet toward redemption and self-sufficiency. Tryan's selfless devotion to his needy parishioners takes his toll on his health, however, and he succumbs to illness and dies young.[14]

Reception and Criticism

The publication of Amos Barton caused some alarm among those who - rightly or wrongly - suspected that they had been the models for the characters, few of whom are described in a flattering manner. Eliot was forced to apologise to John Gwyther, who had been the local curate in her childhood, and to whom the character of Barton himself bore more than a passing resemblance.[15]

Initial criticism of Amos Barton was mixed, with Blackwood's close friend W G Hamley "dead against Amos" and Thackeray diplomatically noncomittal.[16] However, the complete Scenes of Clerical Life was met with 'just and discerning applause', and considerable speculation as to the identity of its author.[17] It was praised for its realism: one contemporary review noted approvingly that "the fictitious element is securely based upon a broad groundwork of actual truth, truth as well in detail as in general".[18] Due to its subject matter, it was widely assumed to be the work of a real-life country parson; one such even attempted to take the credit. [19] In 1858 Charles Dickens wrote to Eliot to express his approval of the book, and was among the first to suggest that Scenes of Clerical Life might have been written by a woman.[20]

I have been so strongly affected by the two first tales in the book you have had the kindness to send me, through Messrs. Blackwood, that I hope you will excuse my writing to you to express my admiration of their extraordinary merit. The exquisite truth and delicacy both of the humor and the pathos of these stories, I have never seen the like of; and they have impressed me in a manner that I should find it very difficult to describe to you. if I had the impertinence to try. In addressing these few words of thankfulness to the creator of the Sad Fortunes of the Rev. Amos Barton, and the sad love-story of Mr. Gilfil, I am (I presume) bound to adopt the name that it pleases that excellent writer to assume. I can suggest no better one: but I should have been strongly disposed, if I had been left to my own devices, to address the said writer as a woman. I have observed what seemed to me such womanly touches in those moving fictions, that the assurance on the title-page is insufficient to satisfy me even now. If they originated with no woman, I believe that no man ever before had the art of making himself mentally so like a woman since the world began.[21]

Subsequent Releases and Interpretations

Scenes of Clerical Life has been reprinted in book form several times since 1858. The three stories were released separately by Hesperus Press over the years 2003 to 2007. A silent film based on "Mr Gilfil's Love Story" was released in 1920, starring R. Henderson Bland as Maynard Gilfil and Mary Odette as Caterina.[22]

References

- ^ Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.accessed 10 October 2008.

- ^ Eliot, George, and Jennifer Gribble. Scenes of Clerical Life. New York: Penguin, 1985.[1]

- ^ Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.accessed 14 October 2008.

- ^ Eliot, George. 'Silly Novels by Lady Novelists'. Westminster Review, 66 (October 1856): 442-61.[2]

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" The Guardian, 6 January 2007. accessed 21 October 2008

- ^ Cross, George Eliot's life as related in her letters and journals, New York 1965: AMS Press Inc., p. 169

- ^ Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.accessed 14 October 2008.

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" The Guardian, 6 January 2007. accessed 21 October 2008

- ^ [3]

- ^ Scenes from Clerical Life

- ^ George Eliot: Review of Scenes of Clerical Life - Warwickshire Web

- ^ Scenes of Clerical Life Book Review

- ^ [4]

- ^ Scenes from Clerical Life

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" The Guardian, 6 January 2007. accessed 21 October 2008

- ^ Hughes, Kathryn. "The Mystery of Amos Barton" The Guardian, 6 January 2007. accessed 21 October 2008

- ^ [5]

- ^ The Atlantic Monthly, May 1858. [accessed 21 October 2008]

- ^ accessed 14 October 2008. Uglow, Nathan. "Scenes of Clerical Life". The Literary Encyclopedia. 30 October 2002.

- ^ Crompton, Margaret. George Eliot, the Woman. New York: T. Yoseloff, 1960. Page 17.[6]

- ^ Moulton, Charles Wells. The Library of Literary Criticism of English and American Authors. Buffalo New York: Moulton, 1904. vol. 7, page. 181.[7]

- ^ Mr Gilfil's Love Story at International Movie Database

External links

- Scenes of Clerical Life – searchable online e-text posted by Peter Batke at Princeton University

- Scenes of Clerical Life, Estes and Lauriat, 1894. Scanned illustrated book via Google Books

- Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, January 1957 - scanned magazine containing the first part of The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton