Landslide: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Capricorn42 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 125.212.64.128 to last version by 72.93.200.130 (HG) |

||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

Evidence of past landslides has been detected on many bodies in the solar system, but since most observations are made by probes that only observe for a limited time and most bodies in the solar system appear to be geologically inactive not many landslides are known to have happened in recent times. Both Venus and Mars have been subject to long-term mapping by orbiting satellites, and examples of landslides have been observed on both. |

Evidence of past landslides has been detected on many bodies in the solar system, but since most observations are made by probes that only observe for a limited time and most bodies in the solar system appear to be geologically inactive not many landslides are known to have happened in recent times. Both Venus and Mars have been subject to long-term mapping by orbiting satellites, and examples of landslides have been observed on both. |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

Revision as of 02:46, 10 November 2008

This article needs attention from an expert in Geology. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (November 2007) |

A landslide is a geological phenomenon which includes a wide range of ground movement, such as rock falls, deep failure of slopes and shallow debris flows, which can occur in offshore, coastal and onshore environments. Although the action of gravity is the primary driving force for a landslide to occur, there are other contributing factors affecting the original slope stability. Typically, pre-conditional factors build up specific sub-surface conditions that make the area/slope prone to failure, whereas the actual landslide often requires a trigger before being released.

Causes of landslides

Landslides are caused when the stability of a slope changes from a stable to an unstable condition. A change in the stability of a slope can be caused by a number of factors, acting together or alone:

Natural causes:

- groundwater pressure acting to destabilize the slope

- Loss or absence of vertical vegetative structure, soil nutrients, and soil structure.

- erosion of the toe of a slope by rivers or ocean waves

- weakening of a slope through saturation by snowmelt, glaciers melting, or heavy rains

- earthquakes adding loads to barely-stable slopes

- earthquake-caused liquefaction destabilizing slopes (see Hope Slide)

- volcanic eruptions

Human causes:

- vibrations from machinery or traffic

- blasting

- earthwork which alters the shape of a slope, or which imposes new loads on an existing slope

- in shallow soils, the removal of deep-rooted vegetation that binds colluvium to bedrock

- Construction, agricultural, or forestry activities which change the amount of water which infiltrates into the soil.

Types of landslide

This article appears to contradict the article Landslide classification. |

Debris flow

Slope material that becomes saturated with water may develop into a debris flow or mud flow. The resulting slurry of rock and mud may pick up trees, houses, and cars, thus blocking bridges and tributaries causing flooding along its path.

Debris flow is often mistaken for flash flood, but they are entirely different processes.

Muddy-debris flows in alpine areas cause severe damage to structures and infrastructure and often claim human lives. Muddy-debris flows can start as a result of slope-related factors, and shallow landslides can dam stream beds, provoking temporary water blockage. As the impoundments fail, a "domino effect" may be created, with a remarkable growth in the volume of the flowing mass, which takes up the debris in the stream channel. The solid-liquid mixture can reach densities of up to 2 tons/m³ and velocities of up to 14 m/s (Chiarle and Luino, 1998; Arattano, 2003). These processes normally cause the first severe road interruptions, due not only to deposits accumulated on the road (from several cubic metres to hundreds of cubic metres), but in some cases to the complete removal of bridges or roadways or railways crossing the stream channel. Damage usually derive from a common underestimation of mud-debris flows: in the alpine valleys, for example, bridges are frequently destroyed by the impact force of the flow because their span is usually calculated only for a water discharge. For a small basin in the Italian Alps (area = 1.76 km²) affected by a debris flow, Chiarle and Luino (1998)[citation needed] estimated a peak discharge of 750 m3/s for a section located in the middle stretch of the main channel. At the same cross section, the maximum foreseeable water discharge (by HEC-1), was 19 m³/s, a value about 40 times lower than that calculated for the debris flow that occurred.

Earth flow

Earthflows are downslope, viscous flows of saturated, fine-grained materials, which move at any speed from slow to fast. Typically, they can move at speeds from .17 to 20 km/h. Though these are a lot like mudflows, overall they are slower moving and are covered with solid material carried along by flow from within. They are different from fluid flows in that they are more rapid. Clay, fine sand and silt, and fine-grained, pyroclastic material are all susceptible to earthflows. The velocity of the earthflow is all dependent on how much water content is in the flow itself: if there is more water content in the flow, the higher the velocity will be.

These flows usually begin when the pore pressures in a fine-grained mass increase until enough of the weight of the material is supported by pore water to significantly decrease the internal shearing strength of the material. This thereby creates a bulging lobe which advances with a slow, rolling motion. As these lobes spread out, drainage of the mass increases and the margins dry out, thereby lowering the overall velocity of the flow. This process causes the flow to thicken. The bulbous variety of earthflows are not that spectacular, but they are much more common than their rapid counterparts. They develop a sag at their heads and are usually derived from the slumping at the source.

Earthflows occur much more during periods of high precipitation, which saturates the ground and adds water to the slope content. Fissures develop during the movement of clay-like material creates the intrusion of water into the earthflows. Water then increases the pore-water pressure and reduces the shearing strength of the material.[2]

Sturzstrom

A sturzstrom is a rare, poorly understood type of landslide, typically with a long run-out. Often very large, these slides are unusually mobile, flowing very far over a low angle, flat, or even slightly uphill terrain. They are suspected of "riding" on a blanket of pressurized air, thus reducing friction with the current underlying surface.

Shallow landslide

Landslide in which the sliding surface is located within the soil mantle or weathered bedrock (typically to a depth from few decimetres to some metres). They usually include debris slides, debris flow, and failures of road cut-slopes. Landslides occurring as single large blocks of rock moving slowly down slope are sometimes called block glides.

Shallow landslides can often happen in areas that have slopes with high permeable soils on top of low permeable bottom soils. The low permeable, bottom soils trap the water in the shallower, high permeable soils creating high water pressure in the top soils. As the top soils are filled with water and become heavy, slopes can become very unstable and slide over the low permeable bottom soils. Say there is a slope with silt and sand as its top soil and bedrock as its bottom soil. During an intense rainstorm, the bedrock will keep the rain trapped in the top soils of silt and sand. As the topsoil becomes saturated and heavy, it can start to slide over the bedrock and become a shallow landslide. R. H. Campbell did a study on shallow landslides on Santa Cruz Island California. He notes that if permeability decreases with depth, a perched water table may develop in soils at intense precipitation. When pore water pressures are sufficient to reduce effective normal stress to a critical level, failure occurs. [3]

Deep-seated landslide

Landslides in which the sliding surface is mostly deeply located below the maximum rooting depth of trees (typically to depths greater than ten meters). Deep-seated landslides usually involve deep regolith, weathered rock, and/or bedrock and include large slope failure associated with translational, rotational, or complex movement.

Causing tsunami

Landslides that occur undersea, or have impact into water, have been know to generate tsunamis. Massive landslides have also been known to generate megatsunamis, which are usually hundreds of metres high.

Related phenomena

- An avalanche, similar in mechanism to a landslide, involves a large amount of ice, snow and rock falling quickly down the side of a mountain.

- A pyroclastic flow is caused by a collapsing cloud of hot ash, gas and rocks from a volcanic explosion that moves rapidly down an erupting volcano.

Historical landslides

- The Agulhas slide, ca. 20,000 km³, off South Africa, post-Pliocene in age, the largest so far described[4]

- The Storegga Slide, Norway, ca. 3,500 km³, ca. 8,000 years ago

- The Ruatoria debris avalanche, off North Island New Zealand, ca. 3,000 km³ in volume, 170,000 years ago[1].

- Landslide which moved Heart Mountain to its current location, Park County, Wyoming, the largest ever discovered on land

- Cliff landslip of the Undercliff near Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, on 24 December 1839

- The Cap Diamant Québec rockslide on September 19, 1889

- Frank Slide, Turtle Mountain, Alberta, Canada, on 29 April 1903

- Khait landslide, Khait, Tajikistan, Soviet Union, on July 10, 1949

- The Riñihuazo landslide in Chile after the Great Chilean Earthquake, on 22 May 1960

- Monte Toc landslide (260 millions cubic metres) falling into the Vajont Dam basin in Italy, causing a megatsunami and about 2000 casualties, on October 9, 1963

- The 1966 Aberfan disaster

- Saint-Jean-Vianney, Quebec, Canada. Small village near Saguenay river destroyed in May 1971.[5]

- Landslides associated with the Mount St. Helens eruption on May 18, 1980.

- Thistle, Utah on 14 April 1983

- The Mameyes Disaster - Ponce, Puerto Rico on October 7, 1985

- Val Pola landslide during Valtellina disaster (1987) Italy

- The Pantai Remis landslide in 1993 in an abandoned coastal tin mine in Malaysia, forming a new cove

- Thredbo landslide, Australia on 30 July 1997

- The Vargas tragedy, due to heavy rains in Vargas State, Venezuela, on December, 1999, causing tens of thousands of casualties.

- Payatas, Manila garbage slide on 11 July 2000.[citation needed]

- Southern Leyte landslide in the Philippines on 17 February 2006

- Devil's Slide, an ongoing landslide in San Mateo County, California

- 2007 Chittagong mudslide, in Chittagong, Bangladesh, on June 11, 2007.

- 2008 Cairo landslide on September 6, 2008.

Extraterrestrial landslides

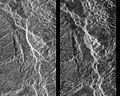

Evidence of past landslides has been detected on many bodies in the solar system, but since most observations are made by probes that only observe for a limited time and most bodies in the solar system appear to be geologically inactive not many landslides are known to have happened in recent times. Both Venus and Mars have been subject to long-term mapping by orbiting satellites, and examples of landslides have been observed on both.

-

Before and after radar images of a landslide on Venus

-

Landslide in progress on Mars

See also

- Automatic Deformation Monitoring System

- Deformation monitoring

- Geotechnics

- Geotechnical engineering

- Earthquake engineering

- Landslide mitigation

- Mass wasting

- Slope stability

- Landslide dam

References

- ^ Kuriakose, S.L., Sankar, G., Muraleedharan, C. (2008) History of landslide susceptibility and a chorology of landslide prone areas in the Western Ghats of Kerala, India. Environmental Geology. DOI: 10.1007/s00254-008-1431-9. URL: http://www.springerlink.com/content/c1q6465428351032/

- ^ Easterbrook, Don J. Surface Processes and Landforms. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1999.

- ^ Renwick,W., Brumbaugh,R. & Loeher,L. 1982. Landslide Morphology and Processes on Santa Cruz Island California. Geografiska Annaler. Series A, Physical Geography, Vol. 64, No. 3/4, pp. 149-159

- ^ Dingle,R.V. 1977. The anatomy of a large submarine slump on a sheared continental margin (SE Africa). Journal of Geological Society London, 134, 293-310.

- ^ Glissement de terrain à Saint-Jean-Vianney | Les Archives de Radio-Canada

External links

- United States Geological Survey site

- European Soil Portal, Landslides

- British Columbia government landslide information

- Slide!, a program on B.C.'s Knowledge Network, with video clips

- Geoscience Australia Fact Sheet [2]

- Pictures of Slope Failure

- JTC1 Joint International Technical Committee on Landslides and Engineered Slopes