Comanche: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

[[Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 085.jpg|thumb|240px|Uwat - Comanche, 1930.]] |

[[Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 085.jpg|thumb|240px|Uwat - Comanche, 1930.]] |

||

mr d is gay |

|||

==Culture== |

==Culture== |

||

===Social order=== |

===Social order=== |

||

Revision as of 18:03, 10 November 2008

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (February 2008) |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| United States (Oklahoma, Texas, | |

| Languages | |

| English, Comanche | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, other | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Shoshone and other Numic peoples |

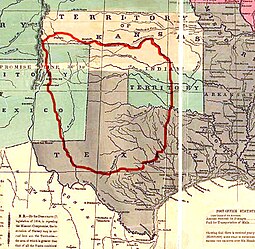

The Comanche Indians are a Native American ethnic group whose range (the Comancheria) consisted of present-day eastern New Mexico, southern Colorado, southern Kansas, all of Oklahoma, and most of northern and southern Texas. Originally, the Comanches were hunters and gatherers, with a typical plains Indian culture. There may have been as many as 45,000 Comanches in the late eighteenth century.[1] Today, the Comanche Nation consists of approximately 10,000 members, about half of whom live in Oklahoma (centered at Lawton), and the remainder are concentrated in Texas, California, and New Mexico. The Comanche speak an Uto-Aztecan language, sometimes classified as a Shoshone dialect.

Name

Though there are various accounts of the origin of the name Comanche, it is generally agreed[2][3] to have come by way of Spanish from the old Ute term *[kɨ.ˈman.ʧi] (modern Southern Ute [kɨ.ˈmaː.ʧi̥]), "enemy, foreigner, Comanche".[4] however, they were not present in that area until later.[5][6][7] The Comanches' own preferred name is Numunuu, meaning "human being" or "the People".[8]

History

Formation

The Comanches emerged as a distinct group shortly before 1700, when they broke off from the Shoshone people living along the upper Platte River in Wyoming. This coincided with their acquisition of the horse, which allowed them greater mobility in their search for better hunting grounds. Their original migration took them to southern plains, from where they moved southward into a sweep of territory extending from the Arkansas River to central Texas. During that time, their population increased dramatically because of the abundance of buffalo, an influx of Shoshone migrants, and the adoption of significant numbers of women and children taken captive from rival groups. Nevertheless, the Comanches never formed a single cohesive tribal unit but were divided into almost a dozen autonomous groups. These groups shared the same language and culture but may have fought among themselves just as often as they cooperated.

The horse was a key element in the emergence of a distinctive Comanche culture, and there have been suggestions that it was the search for additional sources of horses among the settlers of New Spain to the south (rather than the search for new herds of buffalo) that first led the Comanches to break off from the Shoshone. The Comanches may have been the first group of Plains natives to fully incorporate the horse into their culture, and to have introduced the animal to the other Plains peoples.

By the mid-19th century, they were supplying horses to French and American traders and settlers, and later to migrants passing through their territory on their way to the California Gold Rush. Many of these horses had been stolen, and the Comanches earned a reputation as formidable horse, and later, cattle thieves. Their victims included Spanish and American settlers, as well as the other Plains tribes, often leading to war.

They were formidable opponents who developed strategies for fighting on horseback with traditional weapons. Warfare was a major part of Comanche life. The dreaded Comanche raids into Mexico, going as far south as Central America, traditionally took place during the full moon, when the Comanche could see to ride at night. This led to the term "Comanche Moon," during which the Comanche raided for horses, captives, weapons, and simply to spread terror.[9]

Texas-Indian Wars

See Texas–Indian Wars 1820-1875

Relationship with settlers

The Comanches maintained an ambiguous relationship with the Europeans and later settlers attempting to colonize their territory. They were valued as trading partners, but they were also feared for their raids. Similarly, the Comanches were at war at one time or another with virtually every other Native American group living in the Great Plains, leaving opportunities for political maneuvering by the European colonial powers and the United States. At one point, Sam Houston, president of the newly created Republic of Texas, almost succeeded in reaching a peace treaty with the Comanches, but his efforts were thwarted when the Texas legislature refused to create an official boundary between Texas and the Comancheria.

While the Comanches managed to maintain their independence and even increase their territory, by the mid-nineteenth century they faced annihilation because of a wave of epidemics introduced by white settlers. Outbreaks of smallpox (1817, 1848) and cholera (1849) took a major toll on the Comanches, whose population dropped from an estimated 20,000 in mid-century to just a few thousand by the 1870s.

Murder of Robert Neighbors

It was during this period, when settlers began to actually attack the Indians on the reservations established in Texas, that Federal Indian Agent in Charge Robert Neighbors became hated among white Texans. Neighbors alleged that the United States Army officers located at the posts of Fort Belknap and Camp Cooper, near the reservations, failed to give adequate support to him and his resident agents, and adequate protection to the Indians. In spite of continuous threats of various people to take his life, Neighbors never faltered in his determination to do his duty, and carry out the law to protect the Indians.[10]

With the aid of federal troops, who he finally shamed and politically forced to assist him, he managed to hold back the white people from the reservations. Convinced however that the Indians would never be safe in Texas, he determined to move them to safety in the Indian territories. In August 1859 he succeeded in moving the Indians without loss of life to a new reservation in Indian Territory. Forced to return to Texas on business, he stopped at the village near Fort Belknap. On September 14, 1859, while he was speaking with one settler, a man named Edward Cornett shot him in the back while he was talking to the first man, and killed him. Historians believe his assassination was a direct result of his actions protecting the Comanche. Neighbors probably did not even know his assassin. He was buried in the civilian cemetery at Fort Belknap.[11]

Efforts to move the Comanches into reservations began in the late 1860s with the Treaty of Medicine Lodge (1867), which offered them churches, schools, and annuities in return for a vast tract of land totaling over 60,000 square miles (160,000 km²). The government promised to stop the buffalo hunters, who were decimating the great herds of the Plains, provided that the Comanches, along with the Apaches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos, moved to a reservation totaling less than 5,000 square miles (13,000 km²) of land. However, the government elected not to prevent the slaughtering of the herds, which provoked the Comanches under Isa-tai (White Eagle) to attack a group of hunters in the Texas Panhandle in the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (1874). The attack was a disaster for the Comanches, and the army was called in to drive all the remaining Comanche in the area into the reservation. Within just ten years, the buffalo were on the verge of extinction, effectively ending the Comanche way of life as hunters. In 1875, the last free band of Comanches, led by Quahadi warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

Unhappy with life on the reservation, 170 warriors and their families, led by Black Horse, left the reservation in late 1876 for the Llano Estacado. Attacks on buffalo hunters' camps led to the Buffalo Hunters' War of 1877.

In 1892 the government negotiated the Jerome Agreement, with the Comanches, Kiowas, and Apaches, further reducing their reservation to 480,000 acres (1,940 km²) at a cost of $1.25 per acre ($308.88/km²), with an allotment of 160 acres (0.6 km²) per person per tribe to be held in trust. New allotments were made in 1906 to all children born after the Jerome Agreement, and the remaining land was opened to white settlement. With this new arrangement, the era of the Comanche reservation came to an abrupt end.

Modern times

Comanches were ill-prepared for life in a Western economic system, and many of them were defrauded of whatever remained of their land and possessions. Elected chief of the entire tribe by the United States government, Chief Quanah Parker campaigned vigorously for better deals for his people, meeting with Washington politicians frequently; and helped manage land for the tribe. Parker became wealthy as a cattleman. Quanah also campaigned for the Comanches' permission to practice the Native American Church religious rites, such as the usage of peyote,[citation needed] which was condemned by whites. During World War II, many Comanches left the traditional tribal lands in Oklahoma in search of financial opportunities in the cities of California and the Southwest. Today they are among the most highly educated native groups in the United States. About half the Comanche population still lives in Oklahoma, centered around the town of Lawton. In July, Comanches from across the United States gather to celebrate their heritage and culture in Walters, Oklahoma at the annual Comanche Homecoming powwow.

Many Comanches, especially those living in and around Lawton, Oklahoma, claim descent from Quanah Parker {He had five wives and twenty-five children}.

mr d is gay

Culture

Social order

Comanche groups did not have a single acknowledged leader. Instead, a small number of generally recognized leaders acted as counsel and advisors to the group as a whole. These included the "peace chief," the members of the council, and the "war chief."

The peace chief was usually an older individual, who could bring his experience to the task of advising. There was no formal instatement to the position, it being one of general consensus. The council made decisions about where the band should hunt, whether they should war against their enemies, and whether to ally themselves with other bands. Any member could speak at council meetings, but the older men usually did most of the talking.

In times of war, the band selected a war chief. To be chosen for this position, a man had to prove he was a brave fighter. He also had to have the respect of all the other warriors in the band. While the band was at war, the war chief was in charge, and all the warriors had to obey him. After the conflict was over, however, the war chief's authority ended.

The Comanche men did most of the hunting and all of the fighting in the wars. They learned how to ride horses when they were young and were eager to prove themselves in battle. On the plains, Comanche women carried out the demanding tasks of cooking, skinning animals, setting up camp, rearing children, and transporting household goods.

Childbirth

If a woman started labor while the band was in camp, she was moved to a tipi, or a brush lodge if it was summer, and one or more of the older women assisted as midwives. If a woman went into labor while the band was on the move, she simply paused along the trail, gave birth to her child, and after a few hours caught up with the group again. Men were not allowed inside the tipi during or immediately after the delivery.

First, the midwives softened the earthen floor of the tipi and dug two holes. One of the holes was for heating water and the other for the afterbirth. One or two stakes were driven into the ground near the expectant mother's bedding for her to grip during the pain of labor. After the birth, the midwives hung the umbilical cord on a hackberry tree. If the umbilical cord was not disturbed before it rotted it was believed that the baby would live a long and prosperous life.

The newborn was swaddled and remained with its mother in the tipi for a few days. Then the baby was then placed in a cradleboard, and the mother went back to work. She could easily carry the cradleboard on her back, or prop it against a tree where the baby could watch her while she collected seeds or roots. Cradleboards consisted of a flat board attached to which was a basket made from rawhide straps, or a leather sheath that laced up the front. With soft, dry moss as a diaper, the young one was safely tucked into the leather pocket. During cold weather, the baby was wrapped in blankets, and then placed in the cradleboard. The baby remained in the cradleboard for about ten months, then it was allowed to crawl around.

Both girls and boys were welcomed into the band, but boys were favored. If the baby was a boy, one of the midwives informed the father or grandfather, "It's your close friend". Families might paint a flap on the tipi to tell the rest of the tribe that they had been strengthened with another warrior.

Sometimes a man named his child, but mostly the father asked a medicine man (or another man of distinction) to do so. He did this in hope of his child living a long and productive life. During the public naming ceremony, the medicine man lit his pipe and offered smoke to the heavens, earth, and each of the four directions. He prayed that the child would remain happy and healthy. He then lifted the child to symbolize its growing up and announced the child's name four times. He held the child a little higher each time he said the name. It was believed that the child's name foretold its future; even a weak or sick child could grow up to be a great warrior, hunter, and raider if given a name suggesting courage and strength. Boys were often named after their grandfather, uncle, or other relative. Girls were usually named after one of their father's relatives, but the name was selected by the mother. As children grew up they also acquired nicknames.

Children

The Comanche looked upon their children as their most precious gift. Children were rarely punished. Sometimes, though, an older sister or other relative was called upon to discipline a child, or the parents arranged for a boogey man to scare the child. Occasionally, old people donned sheets and frightened disobedient boys and girls. Children were also told about Big Cannibal Owl (Pia Mupitsi) who, they were told, lived in a cave on the south side of the Wichita Mountains and ate bad children at night.

Children learned from example, by observing and listening to their parents and others in the band. As soon as she was old enough to walk, a girl followed her mother about the camp playing at the daily tasks of cooking and making clothing. She was also very close to her mother's sisters, who were called not aunt but "pia", meaning mother. She was given a little deerskin doll, which she took with her everywhere. She learned to make all the clothing for the doll.

A boy identified not only with his father but with his father's family, as well as with the bravest warriors in the band. He learned to ride a horse before he could walk. By the time he was four or five he was expected to be able to skillfully handle a horse. When he was five or six, he was given a small bow and arrows. He was often taught to ride and shoot by his grandfather since his father and other men were on raids and hunts. His grandfather also taught him about his own boyhood and the history and legends of the Comanche.

As the boy grew older, he joined the other boys to hunt birds. He eventually ranged farther from camp looking for better game to kill. Encouraged to be skillful hunters, boys learned the signs of the prairie as they learned to patiently and quietly stalk game. They became more self-reliant, yet, by playing together as a group, also formed the strong bonds and cooperative spirit that they would need when they hunted and raided.

Boys were highly respected because they would become warriors and might die young in battle. As he approached manhood, a boy went on his first buffalo hunt. If he made a kill, his father honored him with a feast. Only after he had proven himself on a buffalo hunt was a young man allowed to go on a war path.

When he was ready to become a warrior, at about age fifteen or sixteen, a young man first "made his medicine" by going on a vision quest (a rite of passage). Following this quest, his father gave the young man a good horse to ride into battle and another mount for the trail. If he had proved himself as a warrior, a Give Away Dance might be held in his honor. As drummers faced east, he and other young men danced. His parents, along with his other relatives and the people in the band, threw presents at his feet – especially blankets and horses symbolized by sticks. Anyone might snatch one of the gifts for themselves, although those with many possessions refrained; they did not want to appear greedy. People often gave away all their belongings during these dances, providing for others in the band but leaving themselves with nothing.

Girls learned to gather berries, nuts, and roots. They carried water and collected wood, and when about twelve years old learned to cook meals, make tipis, sew clothing, and perform other tasks essential to becoming a wife and mother. They were then considered ready to be married.

Marriage

Boys might boldly risk their lives as hunters and warriors, but, when it came to girls, boys were very bashful. A boy might visit a person gifted in love medicine, who was believed to be able to charm the young woman into accepting him. During courtship, the girl often approached the boy. Boys mostly stayed in their tipis, so it was up to the girl to go to the tipi. A boy, however, might approach a girl as she went for wood or water. Since they were not allowed to see each other, they met in secret.

When he wished to marry, a boy offered a gift. The gift was usually one or more horses for the girl's father or guardian. He might also agree to work as a hunter or trader for the family, to convince the girl's family that he would be able to provide for her. Usually a young man asked an uncle or friend to make the offer for him. This messenger brought horses and other goods, spoke briefly with the parents, and left. To avoid embarrassment he did not immediately receive an answer. If the proposal was turned down, the horses were simply released and driven back to the suitor's herd; if accepted, the horses were taken into the father's herd, thereby announcing the engagement. Sometimes a marriage was arranged with an older man of wealth, but girls resisted such unions, often eloping with the young men they truly loved.

Death

Old men who no longer went on the war path had a special tipi called the Smoke Lodge, where they gathered each day. A man typically joined when he became more interested in the past than the future. Boys and women were not allowed inside, and new members underwent an initiation.

A very old and ill person was left behind, or abandoned by everyone other than close family. This was not because they lacked sympathy, but because they were afraid that evil spirits were invading his body. As death approached, the old person gave away his belongings. He made his last medicine, then found a quiet place to lie down and waited to die. After he died, the Comanches immediately buried his body by piling rocks on top. His knees were folded, bound in this position with a rope, and then bathed. The face was painted red and the eyes sealed with clay.

The deceased was attired in the finest available clothing and then laid upon a blanket. Loved ones took a final look at the deceased, and then the body was wrapped in another blanket and tied with buffalo-hide rope. Placed in a sitting position on a horse, the body was taken to the burial place, which was usually a cave, a deep ravine, or a crevice high among the rocks.

The body was placed in a sitting position, or on its side, in a hole, or on the ground, around stacked rocks and wooden poles. In the late nineteenth century some Comanches, especially those living along the Red River, built tree or scaffold burial structures like those used by the Cheyenne and other Plains Indians. The Comanche did not fear death, but death worried them, and they often broke camp after a burial to get away from the place of death.

There was little mourning for the old people who died but intense mourning for a young man who died.

Transportation

When they lived with the Shoshone, the Comanche mainly used dog-drawn travois for transportation. Later they acquired horses from other tribes and from the Spaniards. Since horses are faster, easier to control and able to carry more, this helped with hunting and warfare and made moving camp easier. Being herbivores, horses were also easier to feed than dogs, since meat was a valuable resource.

Food

The Comanche were, initially at least, hunter-gatherers. When they lived in the Rocky Mountains during their migration to the Great Plains, both men and women shared the responsibility of gathering and providing food. When the Comanche reached the plains, hunting came to predominate. Hunting was considered a male activity and was a principal source of prestige.

For meat, the Comanche ate buffalo, elk, black bears, pronghorn, and deer. When game was scarce the men hunted wild mustangs, sometimes eating their own ponies. In later years the Comanche raided Texas ranches and stole longhorn cattle. They did not eat fish or fowl, unless starving, when they would eat virtually any creature they could catch, including armadillos, skunks, rats, lizards, frogs, and grasshoppers.

Buffalo meat and other game was prepared and cooked by the women. The women also gathered wild fruits, seeds, nuts, berries, roots, and tubers — including plums, grapes, juniper berries, persimmons, mulberries, acorns, pecans, wild onions, radishes, and the fruit of the prickly pear cactus. The Comanche also acquired maize, dried pumpkin, and tobacco through trade and raids.

Most meats were roasted over a fire or boiled. To boil fresh or dried meat and vegetables, women dug a pit in the ground, which they lined with animal skins or buffalo stomach and filled with water to make a kind of cooking pot. They placed heated stones in the water until it boiled and had cooked their stew. After they came into contact with the Spanish, the Comanche traded for copper pots and iron kettles, which made cooking easier.

Women used berries and nuts, as well as honey and tallow, to flavor buffalo meat. They stored the tallow in intestine casings or rawhide pouches called parfleches. They especially liked to make a sweet mush of buffalo marrow mixed with crushed mesquite beans. The Comanches sometimes ate raw meat, especially raw liver flavored with gall. They also drank the milk from the slashed udders of buffalo, deer, and elk. Among their delicacies was the curdled milk from the stomachs of suckling buffalo calves, and they also enjoyed buffalo tripe, or stomachs.

Comanche people generally had a light meal in the morning and a large evening meal. During the day they ate whenever they were hungry or when it was convenient. Like other Plains Indians, the Comanche were very hospitable people. They prepared meals whenever a visitor arrived in camp, which led to the belief that the Comanches ate at all hours of the day or night. Before calling a public event, the chief took a morsel of food, held it to the sky, and then buried it as a peace offering to the Great Spirit. Many families offered thanks as they sat down to eat their meals in their tipis.

Comanche children ate pemmican, but this was primarily a tasty, high-energy food reserved for war parties. Carried in a parfleche pouch, pemmican was eaten only when the men did not have time to hunt. Similarly, in camp, people ate pemmican only when other food was scarce. Traders ate pemmican sliced and dipped in honey, which they called Indian bread.

Habitation

Much of the area inhabited by the Comanches was flat and dry, with the exception of major rivers like the Cimarron River, the Pecos River, the Brazos River, and the Red River. The water of these rivers was often too dirty to drink, so the Comanches usually lived along the smaller, clear streams which flowed into them. These streams supported trees which the Comanche used to build shelters.

The Comanche sheathed their teepees with a covering made of buffalo hides sewn together. To prepare the buffalo hides, women first spread them on the ground, then scraped away the fat and flesh with blades made from bones or antlers, and left them in the sun. When the hides were dry, they scraped off the thick hair, and then soaked them in water. After several days, they vigorously rubbed the hides in a mixture of animal fat, brains, and liver to soften the hides. The hides were made even more supple by further rinsing and working back and forth over a rawhide thong. Finally, they were smoked over a fire, which gave the hides a light tan color.

To finish the tipi covering, women laid the tanned hides side by side and stitched them together. As many as twenty-two hides could be used, but fourteen was the average. When finished, the hide covering was tied to a pole and raised, wrapped around the cone-shaped frame, and pinned together with pencil-sized wooden skewers. Two wing-shaped flaps at the top of the tipi were turned back to make an opening, which could be adjusted to keep out the moisture and held pockets of insulating air. With a fire pit in the center of the earthen floor, the tipis stayed warm in the winter. In the summer, the bottom edges of the tipis could be rolled up to let cool breezes in. Cooking was done outside during the hot weather. Tipis were very practical homes for itinerant people. Women, working together, could quickly set them up or take them down. An entire Comanche band could be packed and chasing a buffalo herd within about twenty minutes.The comanche women were the one who did the most work with the food.

Clothing

Comanche clothing was simple and easy to wear. Men wore a leather belt with a breechcloth — a long piece of buckskin that was brought up between the legs and looped over and under the belt at the front and back. Loose-fitting deerskin leggings were worn down to the moccasins and tied to the belt. The moccasins had soles made from thick, tough buffalo hide with soft deerskin uppers. The Comanche men wore nothing on the upper body except in the winter, when they wore warm, heavy robes made from buffalo hides (or occasionally, bear, wolf, or coyote skins) with knee-length buffalo-hide boots. Young boys usually went without clothes except in cold weather. When they reached the age of eight or nine they began to wear the clothing of a Comanche adult. In the 19th century, woven cloth replaced the buckskin breechcloths, and the men began wearing loose-fitting buckskin shirts. They decorated their shirts, leggings and moccasins with fringes made of deer-skin, animal fur, and human hair. They also decorated their shirts and leggings with patterns and shapes formed with beads and scraps of material.

Comanche women wore long deerskin dresses. The dresses had a flared skirt and wide, long sleeves, and were trimmed with buckskin fringes along the sleeves and hem. Beads and pieces of metal were attached in geometric patterns. Comanche women wore buckskin moccasins with buffalo soles. In the winter they, too, wore warm buffalo robes and tall, fur-lined buffalo-hide boots. Unlike the boys, young girls did not go without clothes. As soon as they were able to walk, they were dressed in breechcloths. By the age of twelve or thirteen they adopted the clothes of Comanche women.

Hair and headgear

Comanche people took pride in their hair, which was worn long and rarely cut. They arranged their hair with porcupine quill brushes, greased it and parted it in the center from the forehead to the back of the neck. They painted the scalp along the parting with yellow, red, or white clay (or other colors). They wore their hair in two long braids tied with leather thongs or colored cloth, and sometimes wrapped with beaver fur. They also braided a strand of hair from the top of their head. This slender braid, called a scalp lock, was decorated with colored scraps of cloth and beads, and a single feather.

Comanche men rarely wore anything on their heads. Only after they moved onto a reservation late in the 19th century did Comanche men begin to wear the typical Plains headdress. If the winter was severely cold they might wear a brimless, woolly buffalo hide hat. When they went to war, some warriors wore a headdress made from a buffalo's scalp. Warriors cut away most of the hide and flesh from a buffalo head, leaving only a portion of the woolly hair and the horns. This type of woolly, horned buffalo hat was worn only by the Comanche.

Comanche women did not let their hair grow as long as the men did. Young women might wear their hair long and braided, but women parted their hair in the middle and kept it short. Like the men, they painted their scalp along the parting with bright paint.

Body decoration

Comanche men usually had pierced ears with hanging earrings made from pieces of shell or loops of brass or silver wire. A female relative would pierce the outer edge of the ear with six or eight holes. The men also tattooed their face, arms, and chest with geometric designs, and painted their face and body. Traditionally they used paints made from berry juice and the colored clays of the Comancheria. Later, traders supplied them with vermilion (red pigment) and bright grease paints. Comanche men also wore bands of leather and strips of metal on their arms.

Except for black, which was the color for war, there was no standard color or pattern for face and body painting: it was a matter of individual preference. For example, one Comanche might paint one side of his face white and the other side red; another might paint one side of his body green and the other side with green and black stripes. One Comanche might always paint himself in a particular way, while another might change the colors and designs when so inclined. Some designs had special meaning to the individual, and special colors and designs might have been revealed in a dream.

Comanche women might also tattoo their face or arms. They were fond of painting their bodies and were free to paint themselves however they pleased. A popular pattern among the women was to paint the insides of their ears a bright red and paint great orange and red circles on their cheeks. They usually painted red and yellow around their lips.

Arts and crafts

Because of their frequent travelling, Comanche Indians had to make sure that their household goods and other possessions were unbreakable, and so they did not use pottery which could easily be broken on long journeys. Basketry, weaving, wood carving, and metal working were also unknown among the Comanches. Instead, they depended upon the buffalo for most of their tools, household goods, and weapons. Nearly two hundred different articles were made from the horns, hide, and bones of the buffalo.

Removing the lining of the inner stomach, women made the paunch into a water bag. The lining was stretched over four sticks and then filled with water to make a pot for cooking soups and stews. With wood scarce on the plains, women relied on buffalo chips (dried dung) to fuel the fires that cooked meals and warmed the people through long winters.

Stiff rawhide was fashioned into saddles, stirrups and cinches, knife cases, buckets, and moccasin soles. Rawhide was also made into rattles and drums. Strips of rawhide were twisted into sturdy ropes. Scraped to resemble white parchment, rawhide skins were folded to make parfleches in which food, clothing, and other personal belongings were kept. Women also tanned hides to make soft and supple buckskin, which was used for tipi covers, warm robes, blankets, cloths, and moccasins. They also relied upon buckskin for bedding, cradles, dolls, bags, pouches, quivers, and gun cases.

Sinew was used for bowstrings and sewing thread. Hooves were turned into glue and rattles. The horns were shaped into cups, spoons, and ladles, while the tail made a good whip, a fly-swatter, or a decoration for the tipi. Men made tools, scrapers, and needles from the bones, as well as a kind of pipe, and fashioned toys for their children. As warriors, however, men concentrated on making bows and arrows, lances, and shields. The thick neck skin of an old bull was ideal for war shields that deflected arrows as well as bullets. Since they spent most of each day on horseback, they also fashioned leather into saddles, stirrups, and other equipment for their mounts. Buffalo hair was used to fill saddle pads and was also used in rope and halters.

Language

The language spoken by the Comanche people, Comanche (Numu tekwapu), is a Numic language of the Uto-Aztecan language group. It is closely related to the language of the Shoshone, from which the Comanche diverged around 1700, but a few low-level sound changes inhibit mutual intelligibility. The earliest records of Comanche from 1786 clearly show a dialect of Shoshone, but by the beginning of the 20th century, these sound changes had modified the way Comanche sounded in subtle, but profound, ways. [12][13] Although efforts are now being made to ensure its survival, most speakers of the language are elderly, and less than one percent of the Comanches can speak the language. In the late 19th century, Comanche children were placed in boarding schools where they were discouraged from speaking their native language and even severely punished for doing so. The second generation then grew up speaking English, because it was believed that it was better for them not to know Comanche.

During World War II, a group of seventeen young men referred to as "The Comanche Code Talkers" were trained and used by the U.S. Army to send messages conveying sensitive information that could not be deciphered by the Germans.

See also

- African-Native Americans

- Kiowa

- Native Americans in the United States

- Native American tribe

- One-Drop Rule

- Native American tribes in Nebraska

Notes

- ^ review by Frank McLynn of Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire.

- ^ Hämäläinen, Pekka (1998) "The Western Comanche Trade Center: Rethinking the Plains Indian Trade System" The Western Historical Quarterly 29(4): pp. 485-513, p. 488

- ^ Opler, Marvin K. (January 1943) "The Origins of Comanche and Ute" American Anthropologist New Series, 45(1): pp. 155-158

- ^ Parks, Douglas R. "Synonymy". In "Comanche", Thomas W. Kavanagh (2001). In "Plains", ed. R(April 1949) "White Cat Village" American Antiquity14(4): (Archaeological Researches in the Missouri Basin by the Smithsonian River Basin Surveys and Cooperating Agencies) pp. 285-292, p. 291

- ^ Secoy, Frank R. (October 1951) "The Identity of the "Paduca": An Ethnohistorical Analysis" American Anthropologist New Series, 53(4)(pt. 1): pp. 525-542

- ^ Mayhall, Mildred P. (1962) The Kiowas University of Oklahoma Press, Norman OCLC 419795

- ^ Norall, F. (1988) Bourgmont, explorer of the Missouri, 1698-1725 University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, ISBN 0803233167

- ^ Newcomb, William Wilmon (1972). The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times. University of Texas Press, Austin, OCLC 7675387, p. 157

- ^ The Comanches: Lords of the Southern Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. 1952.

- ^ Handbook of Texas Online - NEIGHBORS, ROBERT SIMPSON

- ^ Comanche-Part Three

- ^ McLaughlin, John E. (1992) "A Counter-Intuitive Solution in Central Numic Phonology," International Journal of American Linguistics 58: pp.158-81

- ^ McLaughlin, John E. (2000) "Language Boundaries and Phonological Borrowing in the Central Numic Languages" In Casad, Gene and Willett, Thomas (eds.) (2000) Uto-Aztecan: Structural, temporal, and geographic perspectives: papers in memory of Wick R. Miller by the Friends of Uto-Aztecan Universidad de Sonora, División de Humanidades y Bellas Artes, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico, pp. 293-304, ISBN 970-689-030-0

Further reading

- Bial, Raymond (2000) Lifeways: The Comanche Benchmark Books, New York, ISBN 0-7614-0864-9, juvenile audience

- Catlin, George and Matthiessen, Peter (1989) North American Indians Viking,. New York, ISBN 0-670-82501-8

- Colbert, David (1998) Eyewitness to the American West: From the Aztec Empire to the Digital Frontier in the word of Those Who Saw It Happen Viking Press, New York, ISBN 0-670-88103-1

- Corwin, Judith Hoffman (2002) Native American Crafts of the Plains and Plateau Franklin Watts, Toronto, ISBN 0-531-12202-6

- Davis, Mary B. (1994) Native America in the Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia Garlend Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8240-4846-6

- De Arment, Robert (1996) Alias Frank Canton University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla., ISBN 0-585-12074-9; pioneer days in Oklahoma and Wyoming

- Debo, Angie. (1949) Oklahoma: Foot-Loose and Fancy-Free University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla., OCLC 11869213

- Fehrenbach, Theodore Reed (1974) The Comanches: The Destruction of a People Knopf, New York, ISBN 0-394-48856-3; republished in 2003 under the title The Comanches: The History of a People Anchor Books, New York, ISBN 1-4000-3049-8

- Foster, Morris W. (1991) Being Comanche: a social history of an American Indian community Univ Of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona, ISBN 0-8165-1367-8

- Frazier, Ian (1989) Great Plains Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, New York, ISBN 0-374-21723-8

- Gibson, Arrel Morgan (1980) The American Indian: Prehistory to Present D.C. Heath, Lexington, Mass., ISBN 0-669-04493-8

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008) The Comanche Empire Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9; originally his 2001 thesis The Comanche Empire: A Study of Indigenous Power, 1700-1875

- John, Elizabeth A. H. (1975) Storms Brewed in Other Men's Worlds: The Confrontation of the Indian, Spanish, and French in the Southwest, 1540-1795 Texas A&M Press, College Station, Texas, ISBN 0-89096-000-3

- Jones, David E. (1974) Sanapia: Comanche Medicine Woman Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, ISBN 0-03-088456-X

- Kenner, Charles (1969) A History of New Mexican-Plains Indian Relations University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla., OCLC 2141

- Lodge, Sally (1992) Native American People: The Comanche Rourke Publications, Inc., Vero Beach, Florida, ISBN 0-86625-390-4, Juvenile audience

- Lund, Bill (1997) Native Peoples: The Comanche Indians Bridgestone Books, Mankato, Minnesota, ISBN 1-56065-478-3, Primary school audience

- Mooney, Martin (1993) The Junior Library of American Indians: The Comanche Indians Chelsea House Publishers, New York, ISBN 0-7910-1653-6, Juvenile audience

- Noyes, Stanley (1993) Los Comanches the horse people, 1751-1845 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, ISBN 0-585-27380-4

- Richardson, Rupert Norval (1933) The Comanche Barrier to South Plains Settlement: A Century and a Half of Savage Resistance to the Advancing White Frontier Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, Calif., OCLC 251275170; reprinted in 1996 by Eakin Press, Austin, Texas, OCLC 36404766

- Rollings, Willard (1989) Indians of North America: The Comanche Chelsea House Publishers, New York, ISBN 1-55546-702-4, Juvenile audience

- Secoy, Frank (1953) Changing Miliitary Patterns on the Great Plains (17th century through early 19th century) (Monograph of the American Ethnological Society, No. 21) J. J. Augustin, Locust Valley, N.Y., OCLC 2830994

- Streissguth, Thomas (2000) Indigenous Peoples of North America: The Comanche Lucent Books, San Diego, Calif., ISBN 1-56006-633-4, Juvenile audience

- Thomas, Alfred Barnaby (1940) The Plains Indians and New Mexico, 1751-1778: A collection of documents illustrative of the history of the eastern frontier of New Mexico University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, OCLC 3626655

- Wallace, Ernest and Hoebel, E. Adamson (1952) The Comanche: Lords of the Southern Plains University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Okla., OCLC 1175397

External links

- Comanche Nation

- The Comanche Language and Cultural Preservation Committee

- Comanche Lodge Learn about the Lords of the Southern Plains!

- Kiowa Comanche Apache Indian Territory Project

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Comanche Indians

- Photographs of Comanche Indians hosted by the Portal to Texas History

- "Comanche" Skyhawks Native American Dedication, accessed 15 August 2005

- "Ted's Arrowheads and Artifacts from the Comancheria" (Ted Dunnegan), accessed 19 August 2005

- History of Native American Tribes: Comanche, accessed 9 August 2005

- "Comanche" on the History Channel, accessed 26 August 2005

- Native Americans: Comanche, accessed 13 August 2005

- "The Texas Comanches" on Texas Indians, accessed 14 August 2005

trash