Easy Rider: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 223: | Line 223: | ||

[[Category:Drug-related films]] |

[[Category:Drug-related films]] |

||

[[Category:Films shot in New Orleans]] |

[[Category:Films shot in New Orleans]] |

||

[[Category:Films shot in New Mexico]] |

|||

[[Category:Hippie movement]] |

[[Category:Hippie movement]] |

||

[[Category:Road movies]] |

[[Category:Road movies]] |

||

Revision as of 21:34, 28 December 2008

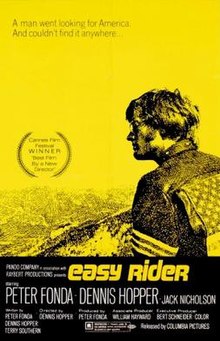

| Easy Rider | |

|---|---|

original movie poster | |

| Directed by | Dennis Hopper |

| Written by | Peter Fonda Dennis Hopper Terry Southern |

| Produced by | Peter Fonda William Leland Hayward Bert Schneider |

| Starring | Peter Fonda Dennis Hopper Jack Nicholson |

| Cinematography | Laszlo Kovacs |

| Edited by | Donn Cambern |

| Music by | Roger McGuinn |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date | July 14, Template:Fy |

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | Template:FilmUS |

| Language | Transclusion error: {{En}} is only for use in File namespace. Use {{langx|en}} or {{in lang|en}} instead. |

| Budget | $340,000-400,000 |

Easy Rider, a Template:Fy American road movie written by Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Terry Southern and directed by Hopper, about two bikers who travel through the American Southwest and South. It stars Fonda, Hopper, and Jack Nicholson and was produced by Fonda. Easy Rider helped spark the New Hollywood phase of filmmaking during the late sixties.

As a landmark counterculture film[1] and "touchstone for a generation" that "captured the national imagination,"[2] Easy Rider explores the societal landscape, issues, and tensions in the United States during the 1960s, such as the rise and fall of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyle.

Plot

The protagonists are two bikers: Wyatt, nicknamed 'Captain America' (Fonda), and Billy (Hopper). Wyatt dresses in American flag-adorned leather, while Billy dresses in Native American-style buckskin pants and shirts and a bushman hat.

After smuggling drugs from Mexico to Los Angeles, Wyatt and Billy sell it to a man (played by Phil Spector) in a Rolls-Royce, in exchange for a large amount of cash. With this money stuffed into the Stars&Stripes-adorned fuel tank of Wyatt's California style chopper, and after a symbolic scene of Wyatt throwing away his watch, they ride eastward in an attempt to reach New Orleans, Louisiana in time for Mardi Gras.

During their trip they pick up a hitch-hiker (Luke Askew) and agree to take him to the commune he is living in. They stay for a few days. Life in the commune appears to be hard, with hippies from the city finding it difficult to grow their own crops. One of the children seen in the commune is played by Fonda's four-year-old daughter Bridget. At one point the bikers witness a prayer for blessing of the new crop, as put by a communard: A chance "to make a stand", and to plant "simple food, for a simple taste." The commune is also host to a traveling theater group that "sings for its supper" (performs for food). The notion of "free love" appears to be practiced, with two women seemingly sharing the affections of the hitch-hiking communard, and who then turn their attention to Wyatt and Billy. As Wyatt and Billy leave, the hitch-hiker (known only as "Stranger on highway" in the credits) gives Wyatt some LSD for him to share with "the right people".

While jokingly riding along with a parade in a small town, the pair are arrested by the local authorities for "parading without a permit." In jail, they befriend alcoholic ACLU lawyer George Hanson (played by Jack Nicholson). George helps them get out of jail and decides to travel with Wyatt and Billy. As they camp that night, Wyatt and Billy introduce George to marijuana. As an alcoholic and a square, George is reluctant to try the marijuana ("It leads to harder stuff"), but he quickly relents.

While attempting to eat in a Louisiana restaurant, the trio's appearance attracts the attention of the locals. The local high school girls in the restaurant want to meet the men and ride with them; the local men and police officer threaten and verbally abuse the riders. One of the men even states, "They won't even make the parish line". Wyatt, Billy and George leave without eating and make camp outside of town. The events of the day cause George to comment: "This used to be a hell of a good country. I can't understand what's gone wrong with it."

In the middle of the night, the local men return and brutally beat the trio while they sleep. Wyatt and Billy suffer minor injuries, but George is killed by a machete strike to the neck. Wyatt and Billy wrap George up in his sleeping bag, gather his belongings, and vow to return the items to his parents.

They continue to New Orleans and find the brothel which had been recommended by George, after having consumed food and wine. Taking two prostitutes, Karen (Karen Black) and Mary (Toni Basil), with them, Wyatt and Billy decide to go outside where the Mardi Gras is going on (see image at right). They wander the parade-filled streets of New Orleans. They end up in a cemetery, where all four ingest LSD. They all experience a psychedelic trip infused with Catholic prayer, represented through quick edits, sound effects and over-exposed film.

In the end, though Billy remains oblivious, Wyatt declares: "You know Billy, we blew it". Wyatt realizes that their search for freedom, while financially successful, was a spiritual failure. The next morning, the two are continuing their trip to Florida (where they hope to retire wealthy) when two locals in a pickup truck (who have a shotgun in their belongings) spot them, and decide to "give them a scare". As they pull alongside Billy and shout at him, he makes an obscene gesture at them. Incensed by this, one of the men takes the shotgun, and shoots at and hits Billy. Wyatt immediately turns around to see his friend crashed and bleeding on the side of the road. Wyatt hops on his bike, hoping to get help for his friend. By then, the men in the truck have turned around. When they see Wyatt speeding towards them on his bike, without a weapon, the redneck in the passenger seat aims at Wyatt and shoots. The shot hits the gas tank of Wyatt's bike, causing it to explode. The explosion not only kills Wyatt, but also destroys the money - which was what they had staked their life on. From the flaming bike on the side of the road, the camera ascends towards the sky, and the duo's journey "looking for America" ends once and for all.

Cast

- Peter Fonda as Wyatt

- Dennis Hopperas Billy

- Jack Nicholson as George Hanson

- Antonio Mendoza as Jesus

- Phil Spector as Connection

- Mac Mashourian as Bodyguard

- Warren Finnerty as Rancher

- Tita Colorado as Rancher's Wife

- Luke Askew as Stranger on Highway

- Luana Anders as Lisa

- Sabrina Scharf as Sarah

- Robert Walker Jr. as Jack

- Sandy Brown Wyeth as Joanne

- Robert Ball as Mime #1

- Carmen Phillips as Mime #2

- Ellie Wood Walker as Mime #3

Production

During the test shooting, Hopper, legendary at the time for his drug excesses and paranoia, tyrannized the crew so much that everyone quit. At one point he entered into a physical confrontation with photographer Barry Feinstein, who was one of the camera operators for the shoot. After the turmoil in New Orleans, Hopper and Fonda decided to assemble a proper crew for the rest of the film.[3]

According to Terry Southern's biographer, Lee Hill, the part of George Hanson had been written for Southern's friend, actor Rip Torn. When Torn met with Hopper and Fonda at a New York restaurant in early 1968 to discuss the role, Hopper began ranting about the "rednecks" he had encountered on his scouting trip to the South. Torn, a Texan, took exception to some of Hopper's remarks, and the two almost came to blows, as a result of which Torn withdrew from the project and had to be replaced by Jack Nicholson. In 1994, Hopper was interviewed about Easy Rider by Jay Leno on The Tonight Show, and during the interview, he alleged that Torn had pulled a knife on him during the altercation, prompting Torn to successfully sue Hopper for defamation.

The hippie commune had to be recreated from pictures and shot near Santa Monica, California overlooking Malibu Canyon, since the New Buffalo commune near Taos in Arroyo Hondo, New Mexico did not permit shooting there.[4]

Most of the film is shot outside with natural lighting. While this can be attributed to the film being a road movie, at the time Hopper said all the outdoor shooting was an intentional choice on his part, because "God is a great gaffer." The production used two five-ton trucks, one for the equipment and one for the motorcycles, with the cast and crew in a motor home.[4] One of the locations was Monument Valley.[4]

The restaurant scenes with Fonda, Hopper and Nicholson were shot in Morganza, Louisiana.[4] The men and girls in that scene were all Morganza locals.[4] In order to incite more vitriolic commentary from the local men, Hopper told them to play the scene as if Billy, Wyatt, and George had raped a girl outside of town. The scene in which both Captain America and Billy were shot was filmed on Highway 105 North just outside of Krotz Springs, Louisiana, and the two men in the scene were Krotz Springs locals.

While shooting the cemetery scene, Hopper tried to convince Fonda to talk to the statue of the Madonna as though it were Fonda's mother (who had committed suicide when he was 10 years old) and ask her why she left him. Although Fonda was reluctant, he eventually complied. Later on, he used this scene as leverage to persuade Bob Dylan to allow the use of "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)".

Despite being filmed in the first half of 1968, roughly between Mardi Gras and the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, with production starting on February 22[5] the film did not have a U.S. premiere until July of 1969, after having won an award at the Cannes film festival in May. The delay was partially due to a protracted editing process. One of Hopper's proposed cuts was 220 minutes long, inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey (film). From his extensive use of the "flash-forward" narrative device, wherein scenes from later in the movie are inserted into the current scene, only one flash-forward survives in the final edit, when Wyatt in the New Orleans brothel has a premonition of the final scene. At the request of Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider, Henry Jaglom was brought in to edit the film into its current form, with Hopper effectively removed from the project. Upon seeing the final cut, Hopper was extremely pleased, claiming that Jaglom had crafted the film the way Hopper had originally intended. Despite the large part he played in shaping the film, Jaglom only received credit as an "Editorial Consultant."

Motorcycles

The motorcycles for the film, based on hardtail frames and Panhead engines, were designed and built by chopper builders Cliff Vaughs and Ben Hardy, following ideas of Peter Fonda, and handled by Tex Hall and Dan Haggerty during shooting.

In total, four former police bikes were used in the film. The 1949, 1950 and 1952 Harley Davidson Hydraglide bikes were purchased at an auction for US$ 500 (equivalent to approx. US$ 2500 at 2007 currency rates). Each bike had a backup to make sure that shooting could continue in case one of the old machines failed or got wrecked accidentally. One "Captain America" was demolished in the final scene, while the other three were stolen and probably taken apart before their significance as movie props became known. The demolished bike was rebuilt by Dan Haggerty and shown in a museum. He sold it at an auction in 2001. Many other replicas have been built since the film’s release.

Hopper and Fonda hosted a wrap party for the movie and then realised they hadn't shot the final campfire scene. Thus, it was shot after the bikes had already been stolen, which is why they are not visible in the background as in the other campfire scenes.[6]

Responses

A box office hit with a $19 million intake, along with Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, Easy Rider helped kick-start the New Hollywood phase during the late 1960s and early 1970s.[7] The major studios realised that money could be made from low-budget films made by avant-garde directors. Heavily influenced by the French New Wave, the films of the so-called "post-classical Hollywood" came to represent a counterculture generation increasingly disillusioned with its government and the world, the Establishment.[7] The film also made Jack Nicholson a movie star.[7]

The film's success, and the new era of Hollywood that it helped usher in, led to Hopper getting the chance to direct again, making whatever film he wanted with complete artistic control. This turned out to be 1971's The Last Movie, which was a notable box office and critical failure, effectively ending Hopper's directorial career for well over a decade.

Awards and honors

Hopper received the First Film Award (Prix de la premiere oeuvre) at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival. At the Academy Awards, Jack Nicholson was nominated for Best Actor in a Supporting Role, and the film was also nominated for Best Writing, Story and Screenplay Based on Material Not Previously Published or Produced.

The film appears at number 88 on the American Film Institute's list of 100 Years, 100 Movies. In 1998, Easy Rider was added to the United States National Film Registry, having been deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

American Film Institute recognition

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies #88

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Songs #29

- AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #84

Music

The movie's "groundbreaking"[8] soundtrack featured The Band, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, and Steppenwolf.[8] Crosby, Stills, & Nash (CSN) were considered for the soundtrack. However, editor Donn Cambern used various music from his own record collection to make watching hours of bike footage more interesting during editing.[4] Most of Cambern's music was used, with licensing costs of $1 million, more than the budget of the film.[4] When CSN viewed a rough cut of the film, they assured Hopper that they could not do any better than he already had.

Bob Dylan was asked to contribute music, but was reluctant to use his own recording of "It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding)", so a version performed by Byrds frontman Roger McGuinn was used instead. Also, instead of writing an entirely new song for the film, Dylan simply wrote out the first verse of “Ballad of Easy Rider” and told the filmmakers, “Give this to McGuinn, he’ll know what to do with it.” McGuinn completed the song and performed it in the film.

In popular culture

- Author Philip K. Dick mentions Easy Rider in his story A Scanner Darkly, in which a character sees the movie in a vision induced while tripping on a reality distortion field created by Scrizer.

- Easy Rider has been cited and parodied many times since. A scene from the film Starsky & Hutch features the titular characters dressed as Wyatt and Billy, riding motorcycles to The Band's "The Weight".

- The movie was also mentioned in the book Steal This Book by Abbie Hoffman; he urged all readers, yippies and hippies to make sure the rest of America did not fall for the image of the Yippies, hippies, and their kind as a group with a (sic) "Easy Rider take-no-crap" image.

- The characters Mike Doonesbury and Mark Slackmeyer of the Doonesbury comic strip embarked on an Easy Rider-style cross-country motorcycle trip in 1972, a story arc that introduced the character of Joanie Caucus.[9]

- The first season finale of Venture Brothers directly parodies the final scene.

- Film buffs will also recall the 1973 film Electra Glide in Blue, starring Robert Blake as a Vietnam War veteran getting his life back together in Arizona as a motorcycle cop. The film inverts the tragic shooting that ends "Easy Rider" by having hippies in a Volkswagen mini-bus blast away with a shotgun at Blake's bike, the Electra Glide.

- In the movie 1986 biopic Sid and Nancy about The Sex Pistols' bassist Sid Vicious and his girlfriend Nancy Spungen there was an Easy Rider poster in Sid and Nancy's apartment.

- After watching the movie, Jimi Hendrix was inspired to write a song about the movie (using different spelling), "Ezy Ryder".[citation needed]

- The man pictured on the cover of The Desert Sessions, volumes 3 & 4 is Peter Fonda from the theatrical poster for the movie.

- In the 1998 film adaptation of Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas Dr. Gonzo whispers "I saw these bastards in 'Easy Rider'. I didn't believe they were real. Not like this, man - not hundreds of them." Whilst, reluctantly, sitting in an anti-drug convention with Thompson.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "Peter Fonda's Easy Rider auction". Boing Boing. 2007-09-16. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "BORN TO BE A CLASSIC: "EASY RIDER" WAS A TOUCHSTONE FOR A GENERATION AND FOR AMERICAN FILMMAKING". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. 2001-07-29. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Easy Rider: Shaking the Cage at IMDb. A Making-of documentary.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Easy Rider: 35 Years Later". Moviemaker.com. 2004-06-24. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://www.moviemaker.com/blog/category/this_day_in_indie_history/P100/

- ^ (as told in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind).

- ^ a b c "Easy Rider (1969)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b "The greatest week in rock history". Salon. 2003-12-19. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Biography of Mike Doonesbury, Doonesbury@Slate.com. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

Bibliography

- Carr, Jay (2002). The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306810964.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hill, Lee (1996). Easy Rider. British Film Institute. ISBN 085170543X.

- Klinger, Barbara (1997). "The Road to Dystopia: Landscaping the Nation in Easy Rider". In Steven Cohan, Ina Rae Hark (ed.). The Road Movie Book. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415149363.

- Lev, Peter (2000). American Films of the 70s: Conflicting Visions. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292747160.

- Osgerby, Bill (2005). Biker: Truth and Myth: How the Original Cowboy of the Road Became the Easy Rider of the Silver Screen. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1592288413.

External links