Corrupt bargain: Difference between revisions

Optimusnauta (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Optimusnauta (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Ford's 1974 Nixon pardon== |

==Ford's 1974 Nixon pardon== |

||

[[Gerald Ford]]'s 1974 [[pardon]] of [[Richard Nixon]] was widely described as a "corrupt bargain" by critics of the disgraced former president. These critics claim that Ford's pardon was [[quid pro quo]] for Nixon's resignation, which elevated Ford to the presidency. The most prominent example was then Representative [[Elizabeth |

[[Gerald Ford]]'s 1974 [[pardon]] of [[Richard Nixon]] was widely described as a "corrupt bargain" by critics of the disgraced former president. These critics claim that Ford's pardon was [[quid pro quo]] for Nixon's resignation, which elevated Ford to the presidency. The most prominent example was then Representative [[Elizabeth Holtzman]] who, as the lowest ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, was the only congressperson to explicitly ask whether the pardon was a quid pro quo. Ford cut Holtzman off and refused to answer the question.<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/29/washington/29pardon.html "For Ford, Pardon Decision Was Always Clear-Cut"]</ref> |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 22:34, 14 January 2009

Three deals cut in connection with the presidency of the United States—two in contested United States presidential elections and a presidential appointment of a vice president—have been described as Corrupt Bargains.

1824

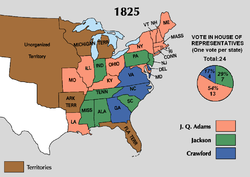

In the U.S. presidential election of 1824, none of the candidates were able to secure the required number of the electoral vote, thereby putting the outcome in the hands of the House of Representatives, which (to the surprise of many) elected John Quincy Adams over rival Andrew Jackson. Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House at the time, convinced Congress to elect Adams. Adams then made Clay his Secretary of State. Some people believe that an agreement was made ahead of time between the two, denounced by the defeated Jackson (who won a plurality of the popular as well as the greatest number of electoral votes) as a "corrupt bargain."[1] Some people also believe that Henry Clay offered Jackson the corrupt bargain.[citation needed] When he was turned down, he took it to John Quincy Adams. Jackson referred to Clay as "The Judas of the West," and remarked that his end would be the same.[citation needed]

More recently, analysis by means of game theory mathematics has proposed that, contrary to the assertions of Jackson, his supporters, and countless historians since, the results of the election were consistent with "sincere voting" -- that is, those who were unable to vote for their most-favored candidate apparently voted for their second- (or third-) most-favored candidate.[2] This suggests that the result was not a consequence of any "corrupt bargain" between Adams and Clay, but was instead a natural consequence of an electoral field that was fundamentally divided between those who supported Jackson and those who would support anyone other than Jackson. The latter united behind Adams - who was the natural alternative to Jackson, since third place candidate William H. Crawford was in poor health and had no realistic chance of winning the House vote - and so prevailed. The persistence of the "corrupt bargain" charge appears, therefore, to be the subject of serious dispute.

1876

The presidential election of 1876 is sometimes considered to be a second "corrupt bargain."[3] Three Southern states had contested vote counts, and for either candidate to win the election, he would need the electoral votes of those states. Congress appointed a special Electoral Commission after the election remain unresolved for three months. In Congress, an agreement was made: Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate, would be elected under the following conditions:

- Hayes's cabinet would include one Southerner (David M. Key of Tennessee was chosen to serve as Postmaster General).

- The Union troops would withdraw from the South.

- A policy of noninterference from Hayes.

- Reconstruction would be declared finished.

Hayes' detractors labeled the compromise a "Corrupt Bargain"[4] and he was widely derided with the nickname "Rutherfraud".[5] With the Union troops gone, there was no security that the South would uphold the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments, so African-Americans were not guaranteed to be free. Hence, it was called a Corrupt Bargain. Many historians call this "The Compromise of 1877".

Ford's 1974 Nixon pardon

Gerald Ford's 1974 pardon of Richard Nixon was widely described as a "corrupt bargain" by critics of the disgraced former president. These critics claim that Ford's pardon was quid pro quo for Nixon's resignation, which elevated Ford to the presidency. The most prominent example was then Representative Elizabeth Holtzman who, as the lowest ranking member of the House Judiciary Committee, was the only congressperson to explicitly ask whether the pardon was a quid pro quo. Ford cut Holtzman off and refused to answer the question.[6]

References

- ^ "The Election of 1824 Was Decided in the House of Representatives: The Controversial Election was Denounced as 'The Corrupt Bargain'", Robert McNamara, Answers.com

- ^ Jenkins, Jeffrey; Sala, Brian (1998), "The Spatial Theory of Voting and the Presidential Election of 1824", American Journal of Political Science, 42 (4): 1157–1179

- ^ "Election 2000 much like Election 1876", Wes Allison, St. Petersburg Times, November 17, 2000

- ^ Carpetbaggers, Cavalry, and the Ku Klux Klan: Exposing the Invisible Empire During Reconstruction (The American Crisis Series: Books on the Civil War Era). Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 2007. ISBN 0-7425-5078-8.

- ^ "A pill too bitter to swallow", guardian.co.uk, Sunday November 12 2000

- ^ "For Ford, Pardon Decision Was Always Clear-Cut"