History of Madagascar: Difference between revisions

Create section for the Sakalava |

→Rise of the Sakalava: an early draft from what can be found in wiki already |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

== Rise of the Sakalava == |

== Rise of the Sakalava == |

||

The island's chiefs began to extend their power through trade with their [[Indian Ocean]] neighbours, notably [[East Africa]], the [[Middle East]] and [[India]]. Large chiefdoms began to dominate considerable areas of the island. Among these were the Sakalava chiefdoms of the [[Menabe]], centred in what is now the town of [[Morondava]], and of [[Boina]], centered in what is now the provincial capital of [[Mahajanga]] (Majunga). The influence of the Sakalava extended across what are now the provinces of [[Antsiranana]], Mahajanga and Toliara. |

|||

According to local tradition, the founders of the Sakalava kingdom were Maroseraña (or Maroseranana, "those who owned many ports") princes, from the [[Fiherenana]] (now Toliara). They quickly submitted the neighbouring princes, starting with the southern ones, in the Mahafaly area. The true founder of Sakalava dominance was Andriamisara; his son Andriandahifotsy (c1610-1658) then extended his authority northwards, past the Mangoky River. His two sons, Andriamanetiarivo and Andriamandisoarivo, extended gains further up to the Tsongay region (now Mahajanga). At about that time, the empire's unity starts to split, resulting in a southern kingdom (Menabe) and a northern kingdom (Boina). Further splits resulted, despite continued extension of the Boina princes' reach into the extreme north, in Antankarana country. |

|||

The Sakalava rulers of this period are known through the memoirs of Europeans such as [[Robert Drury (Sailor)| Robert Drury]], [[James Cook]], Barnvelt (1719), Valentyn (1726). |

|||

== Arrival of European colonists == |

== Arrival of European colonists == |

||

Revision as of 17:38, 1 February 2009

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

The recorded history of Madagascar began in the 7th century when Arabs established trading posts along the northwest coast of the island. Madagascar's prehistory began when the first human settlers arrived, which included a large component from Southeast Asia. This explains the range of Malagasy features, which form a mixture of genotypes from both Austronesians and Africans, as well as later Arab, Indian, and European settlers.

Madagascar became known to Europeans after the Age of Discovery. From the 17th century through the Scramble for Africa, the British and French colonial empires competed for influence in Madagascar. After a brief de facto protectorate period beginning in 1885 the island became a full formal French protectorate in 1890, then a colony in 1896, and gained full independence from France in 1960 in the wake of decolonization.

The first inhabitants

Malagasy mythology portrays a tribe of pale pygmy-like people called the Vazimba as the original inhabitants of Madagascar. In an island whose inhabitants practice ancestor-worship, the inhabitants venerate the Vazimba as the most ancient of ancestors. The kings of some Malagasy regions claim a blood kinship to the Vazimba. Being hunter-gatherers, they would have been largely absorbed by the agricultural Malagasy, repeating a process that has occurred throughout East Africa.

Evidence from faunal extinctions supports this tradition that Madagascar was inhabited prior to the Austronesian immigration. There remain a group of hunter-gatherers on Madagascar, the Mikea, which in their way of life and in their music are completely unlike their Malagasy neighbors. They retained non-Malagasy vocabulary until the 1920s, perhaps a remnant of a Vazimba language. [1]

Austronesian immigration

However, archaeologists generally place the arrival of humans on Madagascar in the centuries between 300 BC and 500 A.D., when seafarers from southeast Asia (Borneo or the southern Celebes) arrived in their outrigger canoes.[2] These were the original Malagasy, who came to the island as part of the great Austronesian expansion, the movement of people that came to dominate in Indonesia and the Pacific Ocean. No evidence of Indonesians colonizing the east coast of Africa has ever surfaced. It appears that the Malagasy came directly across the Indian Ocean from Indonesia, a journey of 3,700 miles, by following the trade-winds and the equatorial east-west current. Anthropologist Jared Diamond has written about the Austronesian expansion to Madagascar, noting many similarities between Malagasy and Indonesians (both cultures cultivating rice in a similar manner and using outrigger canoes, for instance) and differences between Malagasy and Africans (Malagasy favoring rectangular huts as opposed to African round huts, and wearing cloth woven of vegetable fibers as opposed to African animal skins, for instance). Jared Diamond writes of the Austronesians:

These Austronesians, with their Austronesian language and modified Austronesian culture, were already established on Madagascar by the time it was first visited by Europeans, in 1500. This strikes me as the single most astonishing fact of human geography for the entire world. It’s as if Columbus, on reaching Cuba, had found it occupied by blue-eyed, blond-haired Scandinavians speaking a language close to Swedish, even though the nearby North American continent was inhabited by Native Americans speaking Amerindian languages. How on earth could prehistoric people from Borneo, presumably voyaging on boats without maps or compasses, end up in Madagascar?[3].

Arab and Bantu immigration

Medieval Arab navigators and geographers may have known about Madagascar. Various names labelled the island off the southern coast of Ophir (Africa): Phebol, Cernea, Menuthias, Medruthis, Sherbezat, Camarcada, and the Island of the Moon.

Madagascar gets its current name from Marco Polo, (1254 — 1324), the Venetian explorer, who described an African island of untold wealth called Madeigascar in his memoirs (1298 - 1320). Polo heard about the island second-hand during his travels in Asia (1271 - 1295). Most scholars believe that he described Mogadishu, the port located in present-day Somalia. Nevertheless, Italian cartographers attached the name "Madagascar" to the island during the Renaissance.

Bantu settlers probably crossed the Mozambique Channel either due to the Austronesians' science of navigation (in which case the earliest was around AD 500, the time of arrival of Bantu populations on the East African coast from Urere, in Central Africa), or due to the Arab traders (in which case after the time of the hegyra, i.e. in 632). Although the majority of words in the Malagasy language have Malayan-Polynesian affinities, a smattering of Bantu-Swahili loanwords — like omby or aombe 'ox' ( < Bantu-Swahili ngumbe) , ondry 'sheep' (< Bantu Swahili ngundri), and others — appears as well. From this evidence, along with genetics research, some anthropologists believe that Austronesians and Bantu settlers probably intermixed "early" (i.e. around AD 1000) in the island’s history, though this mixing might have been done in different degrees, depending on the regions (the central cold regions were surely less mixed than the coastal hottest regions).

Culturally, the Austronesian brought musical instruments like the tube zither/harp valiha (Sanskrit vaadya or vadya 'music instrument'), the amponga (< Austronesian ampung 'drum'), the sodina (Austronesian suling), along with the rice and the taro cultivation. Conversely, the Bantu people brought cultural traits associated with East Africa: a strong interest in cattle, especially on the southern savannahs of Madagascar, where African influences hold the greatest sway, the measure of wealth and social status in terms of cattle, and the outnumbering of zebu to the inhabitants by two or three to one.

According to the traditions of some Malagasy peoples, the first Bantus and Arabs to settle in Madagascar came as refugees from the civil wars that followed the death of Mohammed in 632.[4] Beginning in the tenth or eleventh century, Arabic and Zanzibari slave-traders worked their way down the east coast of Africa in their dhows and established settlements on the west coast of Madagascar. Notably they included the Zafiraminia, traditional ancestors of the Antemoro, Antanosy and other east-coast ethnicities. The last wave of Arab immigrants, the Antalaotra, immigrated from eastern African colonies. They settled the north-west of the island (Majunga area) and introduced, for the first time, Islam to Madagascar.[5] Arab immigrants, though few in number compared to the Indonesians and Bantus, nevertheless left a lasting impression. The Malagasy names for seasons, months, days, and coins come from Arabic origins, as do cultural features such as the practice of circumcision, the communal grain-pool, and different forms of salutation. The Arab magicians, known as the ombiasy, established themselves in the courts of many Malagasy tribal kingdoms. Arab immigrants imposed a patriarchal system of family and clan rule on Madagascar. Before the Arabs, the Malagasies had a Polynesian-style matriarchal system, which confers rights of privilege and property equally on men and women.[6]

Rise of the Sakalava

The island's chiefs began to extend their power through trade with their Indian Ocean neighbours, notably East Africa, the Middle East and India. Large chiefdoms began to dominate considerable areas of the island. Among these were the Sakalava chiefdoms of the Menabe, centred in what is now the town of Morondava, and of Boina, centered in what is now the provincial capital of Mahajanga (Majunga). The influence of the Sakalava extended across what are now the provinces of Antsiranana, Mahajanga and Toliara.

According to local tradition, the founders of the Sakalava kingdom were Maroseraña (or Maroseranana, "those who owned many ports") princes, from the Fiherenana (now Toliara). They quickly submitted the neighbouring princes, starting with the southern ones, in the Mahafaly area. The true founder of Sakalava dominance was Andriamisara; his son Andriandahifotsy (c1610-1658) then extended his authority northwards, past the Mangoky River. His two sons, Andriamanetiarivo and Andriamandisoarivo, extended gains further up to the Tsongay region (now Mahajanga). At about that time, the empire's unity starts to split, resulting in a southern kingdom (Menabe) and a northern kingdom (Boina). Further splits resulted, despite continued extension of the Boina princes' reach into the extreme north, in Antankarana country.

The Sakalava rulers of this period are known through the memoirs of Europeans such as Robert Drury, James Cook, Barnvelt (1719), Valentyn (1726).

Arrival of European colonists

By the fifteenth century Europeans had wrested control of the spice-trade from the Muslims. They did this by by-passing the Middle East and sending their cargo-ships around the Cape of Good Hope to India. The Portuguese mariner Diogo Dias became the first European to set foot on Madagascar when his ship, bound for India, blew off course in 1500. In the ensuing two-hundred years, the English and French tried (and failed) to establish settlements on the island.

Fever, dysentery, hostile Malagasy tribespeople, and the trying arid climate of southern Madagascar soon terminated the English settlement near Toliary (Tuléar) in 1646. Another English settlement in the north in Nosy Bé came to an end in 1649. The French colony at Taolañaro (Fort Dauphin) fared a little better: it lasted thirty years. On Christmas night 1672, local Antanosy tribesmen, perhaps angry because fourteen French soldiers in the fort had recently divorced their Malagasy wives to marry fourteen French orphan-women sent out to the colony, massacred the fourteen grooms and thirteen of the fourteen brides. The Antanosy then besieged the stockade at Taolañaro for eighteen months. A ship of the French East India Company rescued the surviving thirty men and one widow in 1674.

In 1665, François Caron, the Director General of the newly formed French East India Company, sailed to Madagascar. The Company failed to found a colony on Madagascar but established ports on the nearby islands of Bourbon and Île-de-France (today's Réunion and Mauritius respectively). In the late 17th century, the French established trading-posts along the east coast.[citation needed]

Pirates and slave-traders

Between 1680 and 1725, Madagascar became a pirate stronghold. Many unfortunate sailors became shipwrecked and stranded on the island. Those who survived settled down with the natives, or more often, found French or English colonies on the island or even pirate havens and thus become pirates themselves. One such case, that of Robert Drury,[7] resulted in a journal giving one of the few written depictions of southern Madagascar in the 18th century.

Pirate luminaries such as William Kidd, Henry Every, John Bowen, and Thomas Tew made Antongil Bay and Nosy Boraha (St. Mary’s Island) (a small island 12 miles off the north-east coast of Madagascar) their bases of operations. The pirates plundered merchant ships in the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf. They deprived Europe-bound ships of their silks, cloth, spices, and jewels. Vessels captured going in the opposite direction (to India) lost their coin, gold, and silver. The pirates robbed the Indian cargo ships that traded between ports in the Indian Ocean as well as ships commissioned by the East India Companies of France, England, and the Netherlands. The pilgrim fleet sailing between Surat in India and Mocha on the tip of the Arabian Peninsula provided a favorite target, because the wealthy Muslim pilgrims often carried jewels and other finery with them to Mecca. Merchants in India, various ports of Africa, and Réunion Island showed willingness to fence the pirates' stolen goods. The low-paid seamen who manned merchant ships in the Indian Ocean hardly put up a fight, seeing as they had little reason or motivation to risk their lives. The pirates often recruited crewmen from the ships they plundered.

With regard to piracy in Malagasy waters, note the (semi-)legendary accounts of the alleged pirate-state of Libertalia.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Malagasy tribes occasionally waged wars to capture and enslave prisoners. They either sold the slaves to Arab traders or kept them on-hand as laborers. Following the arrival of European slavers, human chattels became more valuable, and the coastal tribes of Madagascar took to warring with each other to obtain prisoners for the lucrative slave-trade. Instead of spears and cutlasses, the tribesmen fought with muskets, musket-balls, and gunpowder that they obtained from Europeans, conducting fierce and brutal wars. On account of their relationship to the pirates on Nosy Boraha, the Betsimisaraka in eastern Madagascar had more firearms than anyone else. They overpowered their neighbors the Antakarana and Tsimihety and even raided the Comoros Islands. As the tribe on the west coast with the most connections to the slave-trade, the Sakalava also had access to guns and powder. They subdued the other tribes on the west coast. Tribal chiefs who failed to capture prisoners for the slave-trade sometimes did the previously unthinkable -— they sold their own people into slavery.

The Merina monarchy

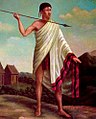

King Andrianampoinimerina

The Merina kingdom In the central highlands of Madagascar, a state of rice-farmers, had lived in relative isolation from the rest of Madagascar for several centuries, but by 1824 the Merina had conquered nearly all of Madagascar — thanks to the leadership of two shrewd kings, Andrianampoinimerina (circa 1745 – 1810) and his son Radama I (1792 – 1828).

By marrying the princesses of different Merina clans and by warring against the princes, Andrianampoinimerina united the Merina kingdom. He established Antananarivo as the capital of Madagascar and built the royal palace, or rova, on a hilltop overlooking the city. The king ambitiously proclaimed: Ny ranomasina no valapariako (“the sea is the boundary of my rice-field”). But Andrianampoinimerina stood out from other ambitious kings and tribal chiefs in his administrative ability. The king codified the laws. He supervised the building of dykes and trenches to increase the amount of arable land around Antananarivo. He introduced the metal spade and compelled rice farmers to use it. He operated as an exemplary military commander. By the time of his death in 1810, he had conquered the Bara and Betsileo highland tribes and had started to prepare to push the boundaries of his kingdom to the shores of the island.

King Radama I (1810 - 1828)

Andrianampoinimerina's son Radama I (Radama the Great) assumed the throne during a turning-point in European history that had repercussions for Madagascar. With the defeat of Napoléon in 1814/1815, the balance of power in Europe and in the European colonies shifted in Britain's favor. The British, eager to exert control over the trade routes of the Indian Ocean, had captured the islands of Réunion and Mauritius from the French in 1810. Although they returned Réunion to France, they kept Mauritius as a base for expanding the British Empire. Mauritius’s governor, to woo Madagascar from French control, recognized Radama I as King of Madagascar, a diplomatic maneuver meant to underscore the idea of the sovereignty of the island and thus to preclude claims by any European powers.

Radama I signed treaties with the United Kingdom outlawing the slave trade and admitting Protestant missionaries into Madagascar. On the face of it, the terms of these treaties seem innocuous enough, but Protestant missionaries (the English knew) would spread British influence as well as Christian charity; and outlawing the slave trade (the English hoped) would weaken Réunion by depriving that island of slave laborers for its sugar plantations. In return for outlawing the slave trade, Madagascar received what the treaty called "The Equivalent": an annual sum of a thousand dollars in gold, another thousand in silver, stated amounts of gunpowder, flints, and muskets, plus 400 surplus British Army uniforms. The governor of Mauritius also sent military advisers who accompanied and sometimes led Merina soldiers in their battles against the Sakalava and Betsimisaraka. In 1824, having defeated the Betsimisaraka, Radama I declared, “Today, the whole island is mine! Madagascar has but one master.” The king died in 1828 while leading his army on a punitive expedition against the Betsimisaraka.

Queen Ranavalona I (1828 - 1861)

The 33-year reign of Queen Ranavalona I (Ranavalona the Cruel), the widow of Radama I, began inauspiciously with the queen murdering the dead king’s heir and other relatives. The aristocrats and sorcerers (who had lost influence under the liberal régime of the previous two Merina kings) re-asserted their power during the reign of Ranavalona I. The queen repudiated the treaties that Radama I had signed with Britain. Emerging from a dangerous illness in 1835, she credited her recovery to the twelve sampy, the talismans — attributed with supernatural powers — housed on the palace grounds. To appease the sampy who had restored her health, she issued a royal edict prohibiting the practice of Christianity in Madagascar, expelled British missionaries from the island, and persecuted Christian converts who would not renounce their religion. Christian customs “are not the customs of our ancestors”, she explained. The queen scrapped the legal reforms started by Andrianampoinimerina in favour of the old system of trial by ordeal. People suspected of committing crimes — most went on trial for the crime of practising Christianity — had to drink the poison of the tangena tree. If they survived the ordeal (which few did) the authorities judged them innocent. Malagasy Christians would remember this period as ny tany maizina, or "the time when the land was dark". By some estimates, 150,000 Christians died during the reign of Ranavalona the Cruel. The island grew more isolated, and commerce with other nations came to a standstill.

Unbeknownst to the queen, her son and heir, the crown-prince (the future Radama II), attended Roman Catholic masses in secret. The young man grew up under the influence of French nationals in Antananarivo. In 1854, he wrote a letter to Napoléon III inviting France to invade Madagascar. On June 28 1855 he signed the Lambert Charter. This document gave Joseph-François Lambert, an enterprising French businessman who had arrived in Madagascar only three weeks before, the exclusive right to exploit all minerals, forests, and unoccupied land in Madagascar in exchange for a 10-percent royalty payable to the Merina monarchy. In years to come, the French would use the Lambert Charter and the prince’s letter to Napoléon III to justify the Franco-Hova Wars and the annexation of Madagascar as a colony. In 1857, the queen uncovered a plot by her son (the future Radama II) and French nationals in the capital to remove her from power. She immediately expelled all foreigners from Madagascar. Ranavalona the Cruel died in 1861.

King Radama II (1861 - 1863)

In his brief two years on the throne, King Radama II re-opened trade with Mauritius and Réunion, invited Christian missionaries[8] and foreigners to return to Madagascar, and re-instated most of Radama I’s reforms. His liberal policies angered the aristocracy, however, and Rainivoninahitriniony, the prime minister, engineered a coup d’état which resulted in the King's death by strangling. The cunning Rainivoninahitriniony or his equally cunning brother, Rainilaiarivory, would rule Madagascar from behind the scenes for the remaining 32 years of the Merina monarchy. First Rainivoninahitriniony and then his brother married Queen Rasoaherina, Radama II’s widow. Rainilaiarivory also married the last two queens of Madagascar, Ranavalona II and Ranavalona III.

Queen Rasoaherina (1863 - 1868)

A council of princes headed by Rainilaiarivony approached Rabodo, the widow of Radama II, the day after the death of her husband. They gave her the conditions under which she could succeed to the throne. These conditions included the suppression of trial by ordeal as well as the monarchy's defense of freedom of religion. Rabodo, crowned queen on May 13, 1863 under the throne name of Rasoaherina, reigned until her death on April 1, 1868.[9]

The Malagasy people remember Queen Rasoaherina for sending ambassadors to London and Paris and for prohibiting Sunday markets. On June 30, 1865, she signed a treaty with the United Kingdom giving British citizens the right to rent land and property on the island and to have a resident ambassador. With the United States of America she signed a trade agreement that also limited the importation of weapons and the export of cattle. Finally, with France the queen signed a peace between her descendants and the descendants of the Emperor of France.[10]

Queen Ranavalona II (1868 - 1883)

In 1869 Queen Ranavalona II, previously educated by the London Missionary Society, underwent baptism into the Church of England and subsequently made the Anglican faith the official state religion of Madagascar.[11] The queen had all the sampy burned in a public display. Catholic and Protestant missionaries arrived in numbers to build churches and schools. The reign of Queen Ranavalona II proved the heyday of British influence in Madagascar. In parts of the island, English replaced French as the second language. Cup, carpet, and other English words entered the Malagasy language. British arms and troops arrived on the island by way of South Africa.

Queen Ranavalona III (1883 - 1897)

Her public coronation as queen took place on November 22, 1883 and she took the name Ranavalona III. As her first order of business she confirmed the nomination of Rainilaiarivony and his entourage in their positions. She also promised to do away with the French threat.[12]

The end of the monarchy

Angry at the cancellation of the Lambert Charter and seeking to restore property confiscated from French citizens, France invaded Madagascar in 1883 in what became known as the first Franco-Hova War (Hova as a name referring to the Merina aristocrats). At the war’s end, Madagascar ceded Antsiranana (Diégo Suarez) on the northern coast to France and paid 560,000 gold francs to the heirs of Joseph-François Lambert. In Europe, meanwhile, diplomats partitioning the African continent worked out an agreement whereby Britain, in order to obtain the Sultanate of Zanzibar, ceded its rights over Heligoland to Germany and renounced all claims to Madagascar in favor of France. The agreement spelled doom for the independence of Madagascar. Prime Minister Rainilaiarivory had succeeded in playing Great Britain and France against one another, but now France could meddle without fear of reprisals from Britain.

In 1895, a French flying-column landed in Mahajanga (Majunga) and marched by way of the Betsiboka River to the capital, Antananarivo, taking the city’s defenders by surprise. (They had expected an attack from the much closer east coast.) Twenty French soldiers died fighting and 6,000 died of malaria and other diseases before the second Franco-Hova War ended. In 1896 the French Parliament voted to annex Madagascar. The 103-year-old Merina monarchy ended with the royal family sent into exile in Algeria.

French control

The British accepted the imposition of a French protectorate over Madagascar in 1890 in return for eventual British control over Zanzibar (subsequently part of Tanzania) and as part of an overall definition of spheres-of-influence in the area.[13]

Malagasy troops fought in France, Morocco, and Syria during World War II. After France fell to the Germans in 1940, the Vichy government administered Madagascar until 1942, when British Empire troops occupied the strategic island in the Battle of Madagascar in order to preclude its seizure by the Japanese. The United Kingdom handed over control of the island to Free French Forces in 1943.

The independent Malagasy Republic

In 1947, with French prestige at a low ebb, the French government, headed by Prime Minister Paul Ramadier of the Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière SFIO party, suppressed the Madagascar revolt, a nationalist uprising. From 80 to 90,000 deaths occurred among the Malagasy during a year of bitter fighting.[14] The French subsequently established reformed institutions in 1956 under the Loi Cadre (Overseas Reform Act), and Madagascar moved peacefully toward independence. The Malagasy Republic, proclaimed on October 14, 1958, became an autonomous state within the French Community. A period of provisional government ended with the adoption of a constitution in 1959 and full independence on June 26, 1960, with Philibert Tsiranana as President.

Tsiranana's rule represented continuation, with French settlers (or colons) still in positions of power. Unlike many of France's former colonies, the Malagasy Republic strongly resisted movements towards communism.[15] In 1972 protests against these policies came to a head and Tsiranana had to step down. He handed power to General Gabriel Ramanantsoa of the army and his provisional government. This régime reversed previous policy in favour of closer ties with the Soviet Union.[16]

On 5 February 1975, Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava became the President of Madagascar. After six days as head of the country, he died in an assassination while driving from the presidential palace to his home. Political power passed to Gilles Andriamahazo.

On 15 June1975 Lieutenant-Commander Didier Ratsiraka (who had previously served as foreign minister) came to power in a coup. Elected president for a seven-year term, Ratsiraka moved further towards socialism, nationalising much of the economy and cutting all ties with France.[16] These policies hastened the decline in the Madagascan economy that had begun after independence as French immigrants left the country, leaving a shortage of skills and technology behind.[15] Ratsiraka's original seven-year term as President continued after his party (Avant-garde de la Révolution Malgache or AREMA) became the only legal party in the 1977 elections.[15] In the 1980s Madagascar moved back towards France, abandoning many of its communist-inspired policies in favour of a market economy, though Ratsiraka still kept hold of power.[17] Eventually opposition — both in Madagascar and internationally — forced him to reconsider his position, and in 1992 the country adopted a new and democratic constitution.[16]

The first multi-party elections came in 1993, with Albert Zafy defeating Ratsiraka.[15] Zafy failed to re-unite the country and suffered impeachment in 1996.[17] The ensuing elections saw a turnout of less than 50% and unexpectedly resulted in the re-election of Didier Ratsiraka.[16] He moved further towards capitalism. The influence of the IMF and World Bank led to widespread privatisation.

Opposition to Ratsiraka began to grow again. Opposition parties boycotted provincial elections in 2000, and the 2001 presidential election produced more controversy. The opposition candidate Marc Ravalomanana claimed victory after the first round (in December) but the incumbent rejected this position. In early 2002 supporters of the two sides took to the streets and violent clashes took place. Ravalomanana claimed that fraud had occurred in the polls. After an April recount the High Constitutional Court declared Ravalomanana president. Ratsiraka continued to dispute the result but his opponent gained international recognition, and Ratsiraka had to go into exile in France, though forces loyal to him continued activities in Madagascar.[15]

Ravlomanana's I Love Madagascar party achieved overwhelming electoral success in December 2001 and he survived an attempted coup in January 2003. He used his mandate to work closely with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to reform the economy, to end corruption and to realise the country's potential.[15] Ratsiraka went on trial (in absentia) for embezzlement (the authorities charged him with taking $8m of public money with him into exile) and the court sentenced him to ten years' hard labour.[18]

Indians in Madagascar

Indians in Madagascar descend mostly from traders who arrived in the newly-independent nation looking for better opportunities. The majority of them came from the west coast of India known as Karana (Muslim) and Banian (Hindu). The majority speak Hindi or Gujarati, and though some other Indian dialects also exist. Nowadays[update] the younger generations speak at least three languages, including French or English, Gujarati and Malagasy. A large number of the Indians in Madagascar have a high level of education, particularly the younger generation, which attempts to contribute their knowledge to the development of Madagascar.[citation needed]

See also

- Rulers of Madagascar

- Andrianampoinimerina

- Radama I

- Ranavalona I

- Rasoherina

- Ranavalona II

- Ranavalona III

- Rainilaiarivony

- Randriamisara

- Merina

- Betsileo

- Antemoro

- Sakalava

- Bara

- Vezo

- Mahafaly

- Tsimihety

- Antakarana

- Tanala

- Bezanozano

- Betsimisaraka

- Antambahoaka

- Antefasy

- Antesaka

- Antandroy

- Makoa

Footnotes

- ^ Archaeology, Language, and the African Past by Roger Blench

- ^ Migration from Kalimantan to Madagascar by O. C. Dahl

- ^ Diamond, Jared (2001) Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, New Edition. New York: W.W. Norton.

- ^ Sigmund Edland, Tantaran’ny Fiangonana Loterana Malagasy

- ^ Sigmund Edland, Tantaran’ny Fiangonana Loterana Malagasy

- ^ Informed Comment

- ^ From Madagascar to the Malagasy Republic by Raymond K. Kent. Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press, 1976. ISBN 0837184215 pages 55-71

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Frédéric Randriamamonjy, Tantaran'i Madagasikara Isam-Paritra (The history of Madagascar by Region), pages 529-534.

- ^ Frédéric Randriamamonjy, Tantaran'i Madagasikara Isam-Paritra (The history of Madagascar by Region), pages 529 - 534

- ^ Madagascar now has three dioceses in the autonomous Church of the Province of the Indian Ocean, part of the Anglican Communion. [1] retrieved on September 14, 2006

- ^ Frédéric Randriamamonjy, Tantaran'i Madagasikara Isam-Paritra (History of Madagascar by Region), pg 546.

- ^ See Allen and Covell, Historical Dictionary of Madagascar, pgs. xxx-xxxi

- ^ The Malagasy "pacification" of 1947 resulted in 89 000 deaths (In French, translation)

- ^ a b c d e f Lonely Planet: Madagascar History

- ^ a b c d BBC: Madagascar timeline

- ^ a b Africa.com: Madagascar history and culture

- ^ BBC News: Ratsiraka gets 10 years hard labor

References

- Mervyn Brown (1978) Madagascar Rediscovered: A history from early times to independence

- Matthew E. Hules, et al (2005). "The Dual Origin of the Malagasy in Island Southeast Asia and East Africa: Evidence from Maternal and Paternal Lineages". American Journal of Human Genetics, 76:894-901, 2005l;.

- Philip M. Allen & Maureen Covell (2005). Historical Dictionary of Madagascar 2nd ed. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4636-5.

- Philip M. Allen (1995). Madagascar: Conflicts of Authority in the Great Island. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-0258-7.

- Raymond K. Kent, From Madagascar to the Malagasy Republic, Greenwood Press, 1962. ISBN 0837184215