Battle of Caishi: Difference between revisions

m Robot - Speedily moving category 12th century conflicts to 12th-century conflicts per CFD. |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Naval battles involving China|Caishi]] |

[[Category:Naval battles involving China|Caishi]] |

||

[[Category:Jurchen history|Caishi]] |

[[Category:Jurchen history|Caishi]] |

||

[[Category:Naval battles of the Medieval era|Caishi]] |

[[Category:Naval battles of the Medieval era|Caishi]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:12th-century conflicts]] |

[[Category:12th-century conflicts]] |

||

[[Category:12th century in China]] |

[[Category:12th century in China]] |

||

Revision as of 15:21, 9 March 2009

| Battle of Caishi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jin-Song wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Jurchen Jin | Southern Song | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Hailingwang | Yu Yunwen | ||||||

The naval Battle of Caishi (采石之战) took place in 1161 and was the result of an attempt by forces of the Jurchen Jin to cross the Yangtze River, thus beginning an invasion of Southern Song China. It followed the Battle of Tangdao on the East China Sea.

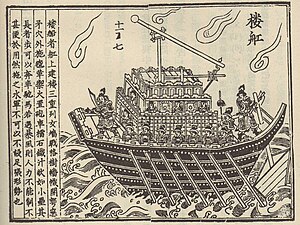

The Song Dynasty navy consisted primarily of paddlewheel ships, which were faster and more maneuverable than the Jin ships, providing the Song with a great advantage. They hid their fleet behind the island of Jinshan, and brought them out at the signal of a mounted scout atop the island's peak. The Song then bombarded the invaders with traction trebuchets, launching "thunderclap bombs", which were soft-cased explosives filled with lime, which would create a noxious cloud when the fuses went off and broke the soft cases.[1] The Jin were so badly defeated that the humiliated Emperor Wanyan Liang (posthumously Hailingwang, "Prince (of) Hailing") of Jin was assassinated by his own men. A subsequent peace treaty signed by both Song and Jin in 1164 would end violence and conflict between the two for four decades to come.

Historical perspectives

An account of this battle was given by the Song naval commander Yang Wanli in his Hai Qiu Fu (Rhapsodic Ode on the Sea-eel Paddle Wheel Warships):

In the xin-si year of the Shao-Xing reign period, the rebels of (Wanyan) Liang came to the north (bank) of the River in force, intending to capture the people's boats, and hoisted flags indicating that they wished to cross over. But our fleet was hidden behind Qibao Shan (island), with orders to come out when a flag signal was given. So a horseman was sent up to the top of the mountain with a hidden flag, and then when the enemy were in mid-stream suddenly the flag appeared; whereupon our ships rushed forth from behind (the island) on both sides. The men inside them paddled fast on the treadmills, and the ships glided forwards as though they were flying, yet no one was visible on board. The enemy thought that they were made of paper. Then all of the sudden a thunderclap bomb was let off. It was made with paper (carton) and filled with lime and sulphur. (Launched from trebuchets) these thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames. The carton case rebounded and broke, scattering the lime to form a smoky fog, which blinded the eyes of men and horses so that they could see nothing. Our ships then went forward to attack theirs, and their men and horses were all drowned, so that they were utterly defeated.[2]

On the significance of this battle and the development of the Song navy, the 20th century historian Joseph Needham states (Wade-Giles spelling):

From a total of 11 squadrons and 3,000 men [the Song navy] rose in one century to 20 squadrons totalling 52,000 men, with its main base near Shanghai. The regular striking force could be supported at need by substantial merchantmen; thus in the campaign of +1161 (AD) some 340 ships of this kind participated in the battles on the Yangtze. The age was one of continual innovation; in +1129 (AD) trebuchets throwing gunpowder bombs were decreed standard equipment on all warships, between +1132 (AD) and +1183 (AD) a great number of treadmill-operated paddle-wheel craft, large and small, were built, including stern-wheelers and ships with as many as 11 paddle-wheels a side (the invention of the remarkable engineer Kao Hsuan), and in +1203 (AD) some of these were armored with iron plates (to the design of another outstanding shipwright Chhin Shih-Fu)...In sum, the navy of the Southern Sung held off the [Jurchen Jin] and then the Mongols for nearly two centuries, gaining complete control of the East China Sea.[3]

See also

- Naval warfare

- Military history of China

- Naval history of China

- History of the Song Dynasty

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

- Gunpowder warfare

- Jiao Yu

Notes

References

- Fighting Ships of the Far East 1 - "China and Southeast Asia 202 BC - AD 1419" (2002) Turnbull, Stephen. Oxford: Osprey Publishing.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Partington, James Riddick (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd.