SARS: Difference between revisions

→Political and economic reaction: ambiguous "for" -> "to conduct", other grammar changes |

|||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

== Clinical information == |

== Clinical information == |

||

=== Symptoms === |

=== Symptoms === |

||

Initial symptoms are flu-like and may include: [[fever]], [[myalgia]], [[lethargy]], [[ |

Initial symptoms are flu-like and may include: [[fever]], [[myalgia]], [[lethargy]], [[Gastrointestinal tract|gastrointestinal]] symptoms, [[cough]], [[sore throat]] and other non-specific symptoms. The only symptom that is common to all patients appears to be a fever above 38 [[Celsius|°C]] (100.4 [[Fahrenheit|°F]]). [[Shortness of breath]] may occur later. |

||

Symptoms usually appear 2–10 days following exposure, but up to 13 days has been reported. In most cases symptoms appear within 2–3 days. About 10–20% of cases require [[mechanical ventilation]]. |

Symptoms usually appear 2–10 days following exposure, but up to 13 days has been reported. In most cases symptoms appear within 2–3 days. About 10–20% of cases require [[mechanical ventilation]]. |

||

Revision as of 13:29, 16 November 2005

| WHO probable cases to 11 July 2003 with some later adjustments** | |||

| Country | Cases | Deaths | Discharged |

| People's Republic of China * | 5327 | 348 | 4941 |

| Hong Kong * | 1755 | 299 | 1433 |

| Taiwan * | 307 | 47 | *** |

| Canada | 250 | 38 | 194 |

| Singapore | 206 | 32 | 172 |

| USA | 71 | 0 | 67 |

| Vietnam | 63 | 5 | 58 |

| Philippines | 14 | 2 | 12 |

| Germany | 10 | 0 | 9 |

| Mongolia | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Thailand | 9 | 2 | 7 |

| France | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| Malaysia | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Italy | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| UK | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| India | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| South Korea | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Sweden | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Indonesia | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Macau * | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Colombia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Finland | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ireland | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Romania | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Russia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| South Africa | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Spain | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 8069 | 775 | 7452 |

| (*) Figures for the People's Republic of China (excluding the Special Administrative Regions), Macau Special Administrative Region, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and the Republic of China (Taiwan) were reported separately by the WHO. | |||

| (**) 11 July 2003 was the last date WHO reported numbers. Totals were later adjusted lower for Republic of China (Taiwan), Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and the United States of America. | |||

| (***)Adjusted total not released. | |||

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is an atypical form of pneumonia. It first appeared in November 2002 in Guangdong Province, China. SARS is now known to be caused by the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), a novel coronavirus. SARS has a mortality rate of around 10%.

After the People's Republic of China suppressed news of the outbreak both internally and abroad, the disease spread rapidly, reaching neighbouring Hong Kong and Vietnam in late February 2003, and then to other countries via international travellers. The last case in this outbreak occurred in June 2003. There were a total of 8,437 cases of disease and 813 deaths.

In May 2005, The New York Times wrote that "not a single case of severe acute respiratory syndrome has been reported this year or in late 2004. It is the first winter without a case since the initial outbreak in late 2002. In addition, the epidemic strain of SARS that caused at least 813 deaths worldwide by June of 2003 has not been seen outside a laboratory since then." [1]

For a timeline of the SARS outbreak, see Progress of the SARS outbreak.

Outbreak in the People's Republic of China

The virus appears to have originated in Guangdong province in November 2002, and despite taking some action to control the epidemic, the People's Republic of China did not inform the World Health Organisation (WHO) of the outbreak until February 2003, restricting coverage of the epidemic in order to preserve face and public confidence. This lack of openness caused the PRC to take the blame for delaying the international effort against the epidemic. [2] The PRC has since officially apologized for early slowness in dealing with the SARS epidemic. [3]

In early April, there appeared to be a change in official policy when SARS began to receive a much greater prominence in the official media. However, it was also in early April that accusations emerged regarding the undercounting of cases in Beijing military hospitals. After intense pressure, PRC officials allowed international officials to investigate the situation there. This has revealed problems plaguing the aging mainland Chinese healthcare system, including increasing decentralization, red tape, and inadequate communication.

In late April, revelations occurred as the PRC government admitted to underreporting the number of cases due to the problems inherent in the healthcare system. Dr. Jiang Yanyong exposed the coverup that was occurring in China, at great personal risk. He reported that there were more SARS patients in his hospital alone than were being reported in all of China. A number of PRC officials were fired from their posts, including the health minister and mayor of Beijing, and systems were set up to improve reporting and control in the SARS crisis. Since then, the PRC has taken a much more active and transparent role in combatting the SARS epidemic.

Spread to other countries

The epidemic reached public spotlight in February 2003, when an American businessman travelling from China came down with pneumonia-like symptoms while on a flight to Singapore. The plane had to stop at Hanoi, Vietnam, where the victim died in a hospital. Several of the doctors and nurses who had attempted to treat him soon came down with the same disease despite basic hospital procedures. Several of them died. The virulence of the symptoms and the infection of hospital staff alarmed global health authorities fearful of another emergent pneumonia epidemic. On March 12, 2003, the WHO issued a global alert, followed by a health alert by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Local transmission of SARS took place in Toronto, Singapore, Hanoi, Taiwan, the Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Shanxi, and the Chinese Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong. In Hong Kong the first cohort of affected people were discharged from the hospital on March 29 2003. The disease spread in Hong Kong from a mainland doctor on the 9th floor of Metropole Hotel in Kowloon Peninsula, infecting 16 of the hotel visitors. Those visitors travelled to Singapore and Toronto, spreading SARS to those locations.

The Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control (CDC) announced in early April their belief that a strain of coronavirus, possibly a strain never seen before in humans, is the infectious agent responsible for the spread of SARS. [4] Disease transmission is currently not well understood. It is suspected to spread via inhalation of droplets expelled by an infected person when coughing or sneezing, or possibly via contact with secretions on objects. Health authorities are also investigating the possibility that it may be airborne, which would increase the potential contagiousness of the disease.

The chances that SARS-infected people could be "asymptomatic," meaning that carriers could be infectious without developing any of the tell-tale signs and hence move around within a population undetected, are small, WHO officials said. "If asymptomatic carriers were playing an important role we would see it by now," WHO spokesman Dick Thompson told Reuters in April of 2004.

Clinical information

Symptoms

Initial symptoms are flu-like and may include: fever, myalgia, lethargy, gastrointestinal symptoms, cough, sore throat and other non-specific symptoms. The only symptom that is common to all patients appears to be a fever above 38 °C (100.4 °F). Shortness of breath may occur later.

Symptoms usually appear 2–10 days following exposure, but up to 13 days has been reported. In most cases symptoms appear within 2–3 days. About 10–20% of cases require mechanical ventilation.

Physical signs

Early physical signs are inconclusive and may be absent. Some patients will have tachypnea and rales on auscultation. Later, tachypnea and lethargy become more prominent.

Investigations

The Chest X-ray (CXR) appearance of SARS is variable. There is no pathognomonic appearance of SARS but is commonly felt to be abnormal with patchy infiltrates in any part of the lungs. The initial CXR may be clear.

White blood cell and platelet counts are often low. Early reports indicated a tendency to relative neutrophilia and a relative lymphopenia — relative because the total number of white blood cells tends to be low. Other suggestive laboratory tests are raised lactate dehydrogenase and slightly raised creatine kinase and C-Reactive protein levels.

Diagnostic tests

With the identification and sequencing of the DNA of the coronavirus supposedly responsible for SARS on April 12, 2003, several diagnostic test kits have been produced and are now being tested for their suitability for use.

Three possible diagnostic tests have emerged, each with drawbacks. The first, an ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) test detects antibodies to SARS reliably but only 21 days after the onset of symptoms. The second, an immunofluorescence assay, can detect antibodies 10 days after the onset of the disease but is a labour and time intensive test, requiring an immunofluorescence microscope and an experienced operator. The last test is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test that can detect genetic material of the SARS virus in specimens ranging from blood, sputum, tissue samples and stool. The PCR tests so far have proven to be very specific but not very sensitive. This means that while a positive PCR test result is strongly indicative that the patient is infected with SARS, a negative test result does not mean that the patient does not have SARS.

The WHO has issued guidelines for using these diagnostic tests [5].

There is currently no rapid screening test for SARS and research is ongoing.

Diagnosis

SARS may be suspected in a patient who has:

- any of the symptoms including a fever of 38 degrees Celsius (100.4 degrees Fahrenheit) or more AND

- either a history of

A probable case of SARS has the above findings plus positive chest x-ray findings of atypical pneumonia or respiratory distress syndrome.

With the advent of diagnostic tests for the coronavirus probably responsible for SARS, the WHO has added the category of "laboratory confirmed SARS" for patients who would otherwise fit the above "probable" category who do not (yet) have the chest x-ray changes but do have positive laboratory diagnosis of SARS based on one of the approved tests (ELISA, immunofluorescence or PCR).

Mortality rate

The mortality rate varies across countries and reporting organizations. In early May, for consistency with similar metrics of other diseases, the World Health Organization (WHO) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was quoting 7%, or the number of deaths divided by probable cases, as the SARS mortality rate. Others spoke in favour of a 15% figure, derived from number of death divided by the number who recovered or died, saying it reflects the real situation more accurately. As the outbreak progressed both mortality measures approached 10%.

One reason for the difficulties in plotting a reliable mortality figure is that the number of infections and the number of deaths are increasing at completely different rates. A possible explanation involves a secondary infection as a causal agent in the disease (See Eric Lerner's analysis), but whatever the cause, the mortality numbers are bound to change.

Mortality by age group as of 8 May 2003 is below 1% for people aged 24 or younger, 6% for those 25 to 44, 15% in those 45 to 64 and more than 50% for those over 65. [7]

For comparison, the case fatality rate for influenza is usually about 0.6% (primarily among the elderly) but can rise as high as 33% in locally severe epidemics of new strains. The mortality rate of the primary viral pneumonia form is about 70%.

Treatment

Antibiotics have not proven to be effective. Treatment of SARS so far has been largely supportive with anti-pyretics, supplemental oxygen and ventilatory support as needed.

Suspected cases of SARS must be isolated, preferably in negative pressure rooms, with full barrier nursing precautions taken for any necessary contact with these patients.

There was initially anecdotal support for steroids and the antiviral drug ribavirin, but no published evidence has supported this therapy. Many clinicians now suspect that ribavirin is detrimental.

Researchers are currently testing all known antiviral treatments for other diseases including AIDS, hepatitis, influenza and others on the SARS-causing coronavirus.

There may be some benefit from using steroids and other immune system modulating agents in the treatment of the more acute SARS patients as there is some evidence that part of the more serious damage SARS causes is also due to the body's own immune system overreacting to the virus. Research is continuing in this area.

In December 2004 it was reported that Chinese researchers had produced a SARS vaccine. It has been tested on a group of 36 volunteers, 24 of whom developed antibodies against the virus.

Current state of etiologic knowledge

The etiology of SARS is still being explored. On April 7, 2003, WHO announced that it was generally agreed that a newly identified coronavirus is the major causative agent of SARS, and that the significance of a human metapneumovirus (hMPV) in SARS remains unclear and would continue to be studied. [8] This was followed by an announcement on April 16 that scientists at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands have confirmed that the virus causing SARS is indeed the new coronavirus. In the experiments, monkeys were infected with the coronavirus, and it was observed that they developed the same symptoms as human SARS victims.

Initially, electron microscopic examination in Hong Kong and Germany found viral particles with structures suggesting paramyxovirus in respiratory secretions of SARS patients; subsequently, in Canada, electron microscopic examination found viral particles with structures suggestive of metapneumovirus (a subtype of paramyxovirus) in respiratory secretions. Chinese researchers also reported that a chlamydia-like disease may be behind SARS. The Pasteur Institute in Paris identified coronavirus in samples taken from six patients. The CDC, however, noted viral particles in affected tissue (finding a virus in tissue rather than secretions suggests that it is actually pathogenic rather than an incidental finding). On electron microscopy, these tissue viral inclusions resembled coronaviruses, and comparison of viral genetic material obtained by PCR with existing genetic libraries suggested that the virus was a previously unrecognized coronavirus. Sequencing of the virus genome—which computers at the British Columbia Cancer Agency in Vancouver completed at 4 a.m. Saturday, April 12, 2003—was the first step toward developing a diagnostic test for the virus, and possibly a vaccine. [9] A test was developed for antibodies to the virus, and it was found that patients did indeed develop such antibodies over the course of the disease, which is very suggestive that the virus does have a causative role. It is generally agreed that this coronavirus has a causative role in SARS: continued study is underway to test the hypothesis that co-infection with other organisms such as human metapneumovirus may also play a role.

An article published in The Lancet identifies a coronavirus as the probable causative agent.

On April 16, 2003, the WHO issued a press release stating that the coronavirus identified by a number of laboratories was the official cause of SARS. [10]

In late May 2003, studies from samples of wild animals sold as food in the local market in Guangdong, China found that the SARS coronavirus could be isolated from civet cats. This suggests that the SARS virus crossed the species barrier from civet cats; this conclusion is, however, by no means certain as it is certainly possible that the civet cats got the virus from humans and not the other way around or even that the civet cats are a sort of intermediary host. In September 2005, a study was released from China which found that 40 percent of a sample of Horseshoe bats collected near Hong Kong were infected with a close genetic relative of SARS, raising the possibility that SARS originated in bats and spread to humans either directly, or through civet cats. The bats did not show any visible signs of disease. [11]Further investigations are ongoing.

Mapping the genetic code of viruses linked to SARS

On April 12, 2003, scientists working around the clock at the Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia finished mapping the genetic sequence of a coronavirus believed to be linked to SARS. The team was led by Dr. Marco Marra and worked in collaboration with the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control and the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba, using samples from infected patients in Toronto. The map, hailed by WHO as an important step forward in fighting SARS, is being shared with scientists worldwide via the GSC website. See the SARS virus article for more details.

Dr. Donald Low of Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto described the discovery as having been made with "unprecedented speed." [12] A team slaved over the problem 24 hours a day for a mere six days.

As at April 17, 2003 an increase over the previous week in the death rate and especially the increase in deaths in young previously healthy patients has reinforced concerns about the severity of the illness and increased anxiety in cities such as Hong Kong. The reasons for this mortality increase cannot yet be stated with certainty. The following factors may be involved:

- Statistical clustering: It may be in part coincidence that a group of younger deaths have occurred over a short period of time. This can only be adequately assessed by detailed statistical analysis of different cohorts (groups) of patients.

- Late presentations: Patients presenting late in the disease would be expected to have a worse outcome. This has been given as an explanation in a number of cases.

- Drug resistance: This has been proposed as a possible explanation by a Professor of virology from Chinese University. There has been a significant debate in the medical community about the effectiveness of ribavirin. It seems unlikely that the effectiveness would change so dramatically in a short time in young patients.

- Variation in the severity of the disease: This is an important possibility. There have been a number of anecdotal reports that the disease is more severe in the cluster of patients from Amoy Gardens. The W.H.O. considers this as a potentially important factor (16 April Press briefing). One possible explanation for this is that the environmental process involved led to exposure to large amounts of virus. Another suggestion is that a slight change in the coronavirus led to more severe disease in this cluster. Exposure to a larger amount of virus, or a more severe disease could be sufficient to impact even on the young and previously healthy. These hypotheses can be tested by assessing the outcome in this cohort in addition to RNA typing of the virus in order to determine if slight variation is associated with different disease patterns.

- Variation in the level of medical care: This is a possible factor. The first cohort of 138 patients had a mortality rate of 3.6%. This data has been published in The New England Journal of Medicine (http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/NEJMoa030685v2 )

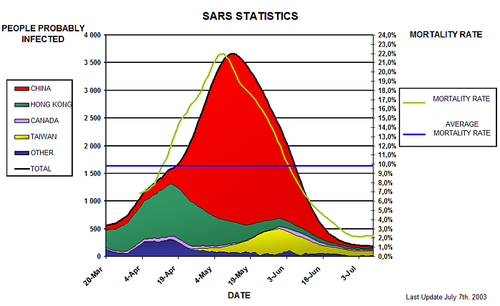

This graphic represents the evolution of the people probably infected, by main countries (Moving Average of 7 days) and the mortality rate for the last 2 weeks.

People probably infected = Cumulative case − Number of deaths − Number of people discharged.

Mortality rate = Deaths / (Deaths + Discharged)

(Source : WHO WEB SITE)

Action implemented to restrict the outbreak of SARS

WHO set up a network for doctors and researchers dealing with SARS, consisting of a secure web site to study chest x-rays and a teleconference.

Attempts were made to control further SARS infection through the use of quarantine. Over 1200 were under quarantine in Hong Kong, while in Singapore and Taiwan, 977 and 1147 were quarantined respectively. Canada also put thousands of people under quarantine. [13] In Singapore, schools were closed for 10 days and in Hong Kong they were closed until 21 April to contain the spread of SARS. [14]

On March 27, 2003, the WHO recommended the screening of airline passengers for the symptoms of SARS. [15]

In Singapore, a single hospital, Tan Tock Seng Hospital, was designated as the sole treatment and isolation centre for all confirmed and probable cases of the disease on 22 March. Subsequently, all hospitals implemented measures whereby all staff members were required to submit to temperature checks twice a day, visitorship was restricted only to paediatric, obstetric and selected other patients, and even then, only one person may visit at a time. To overcome this inconvenience, videoconferencing was utilised. A dedicated phoneline was designated to report SARS cases, whereupon a private ambulance service was dispatched to transport them to Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

On 24 March, Singapore's Ministry of Health invoked the Infectious Diseases Act, allowing for a 10-day mandatory home quarantine to be imposed on all who may have come in contact with SARS patients. SARS patients who have been discharged from hospitals are under 21 days of home quarantine, with telephone surveillance requiring them to answer the phone when randomly called up. Discharged probable SARS patients and some recovered cases of suspected SARS patients are similarly required to be home quarantined for 14 days. Security officers from CISCO, a Singaporean security company, were utilised to serve quarantine orders to their homes, and installed a electronic picture (ePIC) camera outside the doors of each contact.

Sparked in particular by the publicity of an elderly gentlemen who disregarded the quarantine order, flashing it to the public as he strolled to eating outlets and causing a minor exodus of patrons which persisted until the fears over the disease abated, the Singapore government called for an urgent meeting in Parliament on 24 April to amend the Infectious Disease Act and include penalties for violations, revealing at least 11 other violators of their quarantine orders. These amendments include

- the requirement of suspected persons of infectious diseases to be brought to designated treatment centres, and the prohibition of them from going to public places,

- the designation of contaminated areas and the restriction of access to them, and the destruction of suspected sources of infection,

- to introduce the possibility of affixing home quarantine breaking offenders with electronic wrist tags (persons who fail to be contacted three times by phone consecutively will be slapped with the tag), and the imposition of fines without court trial,

- the capability to charge repeated offenders in court which may lead to imprisonment,

- and the prosecution of anyone caught lying to health officials about their travel to SARS-affected areas or contacts with SARS patients.

On 23 April the WHO advised against all but essential travel to Toronto, noting that a small number of persons from Toronto appear to have "exported" SARS to other parts of the world. Toronto public health officials noted that only one of the supposedly exported cases had been diagnosed as SARS and that new SARS cases in Toronto were originating only in hospitals. Nevertheless, the WHO advisory was immediately followed by similar advisories by several governments to their citizens. On 29 April WHO announced that the advisory would be withdrawn on 30 April. Toronto tourism suffered as a result of the WHO advisory, prompting The Rolling Stones and others to organize the massive Molson Canadian Rocks for Toronto concert, commonly known as SARSstock, to re-vitalize the city's tourism trade.

Also on 23 April, Singapore instituted thermal imaging scans to screen all passengers departing Singapore from Singapore Changi Airport. It also stepped up screening of travellers at its Woodlands and Tuas checkpoints with Malaysia. Singapore had previously implemented this screening method for incoming passengers from other SARS affected areas but will move to include all travellers into and out of Singapore by mid to late May. [16]

In addition, students (and some teachers) in Singapore were issued with free personal oral digital thermometers. Students took their temperatures daily; usually two or three times a day, but the temperature taking exercises were suspended with the waning of the outbreak.

Political and economic reaction

The U.S. Library of Congress officially recused itself from attending the American Library Association convention in Toronto in summer 2003 as a precaution.

The 2003 FIFA Women's World Cup, originally scheduled for China, was moved to the United States.

On March 30, the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF) cancelled the 2003 IIHF Women's World Championship tournament which was to take place in Beijing.

On April 1, a European airline laid off a batch of employees owing to a drop in travellers caused by the 11 September attacks and SARS.

Severe customer drop of Chinese cuisine restaurants in Guangdong, Hong Kong and Chinatowns in North America, 90% decrease in some cases. Business recovered considerably in some cities after promotion campaigns.

Some members of Hong Kong Legislative Council recommended editing the budget for increased spending on medical services.

Hong Kong merchants withdrew from an international jewellery and timepiece exhibition at Zürich. Switzerland officials enforced a full body check of the 1000 Hong Kong participants that would be finished 2 days before the end of the exhibition. The Swiss Ambassador to Hong Kong replied that such a body check would guard against spread via close contact. A merchant union leader alleged probable racial discrimination towards Chinese merchants, as the exhibition committee allowed the merchants to participate in the exhibition but not to promote their own goods. An estimated several hundred million HK dollars in contracts were lost as a result. However, exhibitors from Hong Kong were not barred from selling their products in their hotel rooms.

Most conferences and conventions scheduled for Toronto were cancelled, and the production of at least one movie was moved out of the city. On 22 April the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported that the hotel occupancy rate in Toronto was only half the normal rate, and that tour operators were reporting large declines in business. It should be noted that as of 22 April all Canadian SARS cases were believed to be directly or indirectly traceable to the originally identified carriers. SARS is not loose in the community at large in Canada, although a few infected persons have broken quarantine and moved among the general population. No new cases have originated outside hospitals for 20 days.

Nonetheless, on 23 April the WHO extended its travel advice urging postponement of non-essential travel to include Toronto. At the time, city officials and business leaders in the city expected a large economic impact as a result, and an official of the Bank of Canada said that the travel ban would drastically effect Canada's national economy.

On 29 April, WHO announced that its advisory against unnecessary travel to Toronto would be withdrawn on 30 April.

In June, Hong Kong launched the Individual Visit Scheme in order to improve her economy.

In the People's Republic of China, the openness in the latter stage of the SARS crisis showed an unprecedented change in the central government's policies. In the past, rarely had officials stepped down purely because of administrative mistakes, but the case was different with SARS, when these mistakes caused international scrutiny. This change in policy has been largely credited to President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao. At the heart of the crisis, Hu made a high-profile trip to Guangdong and Wen ate lunch with students at Peking University. Some analysts believe the crisis was a blow to former CPC chief Jiang Zemin, who stayed out of the national spotlight during its duration, and whose political allies, such as Health Minister Zhang Wenkang, were fired for irresponsibility and wrongdoings during the SARS crisis. Zhang was replaced by Wu Yi.

Both mainland China and Taiwan were dealing with SARS epidemics at the same time, and the cross-strait politics inevitably complicated the way the disease was handled. Since People's Republic of China insisted on representing the 23 million Taiwanese people in the WHO by itself and forbid the ROC government's participation, Taiwan, which was one of the most endemic areas in the world, did not receive direct advice from WHO. Even though the ROC government actively reported the situation to WHO, the authority received SARS information only through the WHO website.

The ROC claimed that the lack of direct communication with the WHO precluded proper handling of the disease and caused unnecessary deaths on the island. On the other hand, the PRC claimed that video conferences held between her experts and Taiwanese experts already facilitated information distribution and improved the way SARS being treated in Taiwan; the ROC government denied this.

The ROC further advocated its own seats in WHO and used the case of SARS to illustrate the importance to have Taiwan included in the global health monitoring system. However, the PRC saw this as a politically motivated move towards Taiwanese independence. During the WHO general assembly, the People's Republic of China fiercely snubbed the advocation for Taiwan participation. This was evidenced by one famous video clip aired widely in Taiwan about the PRC Vice Premier Wu Yi and her official company rebuffing the question of Taiwan's representation which had been raised by Taiwanese reporters. Under the pressure of PRC, Taiwan was excluded from several major SARS conferences held by WHO. WHO eventually sent its experts to Taiwan to conduct inspections at the end of the SARS endemic; however, PRC claimed the credit.

Accusations of racial discrimination

Some members of some Chinese ethnic communities in some Canadian cities have expressed concern that SARS might lead or has led to racial discrimination and stereotyping. The media in the US and Canada have reported on this topic extensively, although there is no evidence so far of any major racial backlash. Stereotyping in Canada seems to be of possible carriers rather than of racial groups. See SARS and accusations of racial discrimination for more detail.

Laboratory mishandling

Improper handling of the live SARS virus has caused the infection of two researchers in Singapore and one in Taiwan. The discovery of the infection of the Taiwanese researcher, who was visiting Singapore before he was diagnosed as infected, caused Singapore and Taiwan to quarantine 92 people.

People

Possible Cure

In June of 2005, Chinese and European scientists working together reported that a drug used to treat schizophrenia has been shown to prevent and treat acute cases.

External links and references

| SARS | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Pulmonology, infectious diseases, microbiology |

See Severe acute respiratory syndrome: External links for a complete list.

Mainstream news

- SARS in Singapore — Updated frequently by ChannelNewsAsia

- War On SARS — Updated frequently by The Straits Times

- SARS?? — Lianhe Zaobao Chinese SARS news article collage

- Fighting SARS Together — People's Republic of China Xinhua News Agency

- Yahoo! News search — SARS Full Coverage from leading worldwide news organizations

SARS weblogs

- SARS Watch Org — award winning weblog following SARS around the globe — updated daily since March

- Docbear's daily SARS updates — news and analysis written by Canadian doctor

Official announcements

- Official SARS information from the World Health Organization

- Official SARS information from the United States Centers for Disease Control

- Official SARS information from the Hong Kong Department of Health

- Official SARS information from Health Canada (Department of Health)

- Official SARS information from the PRC Ministry of Health

- Official SARS information from the ROC (Taiwan) Center for Disease Control

- Official SARS information from the Singapore Ministry of Health and Ministry of Information and the Arts

Medical mailing lists

- EMED-L mailing list — contains "breaking news" discussion of SARS

- CCM-L mailing list — contains "breaking news" discussion of SARS, notably including the dispatches of the intensive-care specialist Tom Buckley on his work on the ongoing Hong Kong outbreak of SARS

Unofficial sites

- SARS (disease) from Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, University of Iowa.

- SARS: An Open Scar