Destruction of Neuss: Difference between revisions

Auntieruth55 (talk | contribs) m Quick-adding category Eighty Years' War (using HotCat) |

Auntieruth55 (talk | contribs) m moved Destruction of Neuss to Destruction of Neuss (July 1586): page had already been created by GA editor...I didn't know it. |

(No difference)

| |

Revision as of 18:55, 27 July 2009

| Siege of Neuss | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cologne War | |||||||

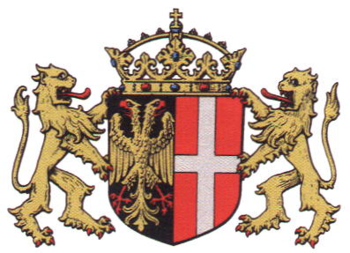

Coat of arms of Neuss. After the city held out in a year-long siege, the emperor granted the right to incorporate imperial arms into the city's coat of arms: the crown and the imperial hawks. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hermann Friedrich von Cloedt † |

Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Garrison: 1600 Dutch and German Artillery: none |

Troops: 8000 infantry, 2000 cavalry Artillery: 45 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Garrison: 100% Civilian and military dead: 4000+ | < 500 | ||||||

The Destruction of Neuss occurred in July 1586, during the Cologne War. Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma's Army of Flanders surrounded the city of Neuss, an important Protestant garrison in the Electorate of Cologne. After the city refused to capitulate, Parma's army reduced the city to rubble, through a combination of brutal artillery fire, destructive house to house fighting, plundering; during the battle, a fire started that destroyed most of the rest of the city. In total, approximately 3000 civilians were killed, of a population of approximately 4500, and the entire garrison was slaughtered.

Situation in 1586

Neuss had been taken by Gebhard's supporters in Februar 1586 by troops of Adolf Count of Moers and Neuenahr. After reinforcing and supplying the city, the Count took most of his troops north, the Moers and Venlo, leaving the young Hermann Friedrich Cloedt in command of the city, with a small garrison of 1600 men, mostly Germans and Dutch soldiers.[1] The town's fortifications were substantial; 100 years earlier it had resisted a lengthy siege by Charles the Bold of Burgundy, and for its efforts, the emperor had granted Neuss the right to mint its own coins and to incorporate the imperial arms in its own coat of arms. The Duke of Parma approached the city, and surrounded its landed fortifications; by some irony, Karl von Mansfeld and his troops, were a part of the Spanish force against the city.[2]

Parma had an impressive force at his command; in addition Mansfeld's 2000 troops, he had another 6000 or so foot and Tercios, plus 2000 mounted, experienced Italian, Spanish and some German soldiers, plus some 45 cannons, which Parma distributed on the redoubt across the river, and on the heights some short distance from the city walls.[3] Prior to the cannonade, Parma requested the capitulation of the city, which was declined, politely. The next day, being the feast of St. James, and the patron day for the Spanish, the battle was not joined, however reports circulated in the Spanish camp that two soldiers, captured in the previous days' sorties, had been roasted alive in the market square.[4]

The Battle

Once the cannonade began, Parma's 45 artillery pounded at the walls for 30 hours with iron cannonballs weighing 30 to 50 pounds, in total 2700 rounds.[5] The Spanish made several attacks, each repelled. With the ninth assault, the outer wall had been breached. Von Cloedt, gravely injured (his leg was reportedly nearly ripped off and he had five other serious wounds), had been carried into the town. The Spanish and Italian forces entered the town from opposing ends, and met in the middle. Parma was reportedly inclined to honor the garrison commander; Ernst demanded his blood.[6] Soldiers found Cloedt and the dying man was hanged from the window, along with several dozen others in his force. Italian and Spanish soldiers, on their rampage through the city, slaughtered the rest of the garrison, even the men who tried to surrender. Women, who had taken refuge in some of the churches, were initially spared, but when the fire started, they were forced into the street. Contemporary accounts refer to children, women, and old men, their clothes in sparks or flames, trying to escape the conflagration, only to be trapped by the enraged soldiers; if they escaped the flames and the Spanish, they were trapped by the enraged Italians. Parma wrote to the king (of Spain) that over 4000 lay dead in the ditches. English observers confirmed this report, and elaborated that only 8 buildings remained standing.[7]

- ^ Leonard Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, v. 5, specifically p. 178. 1880. Google books Accessed 21 July 2009. here

- ^ J. H. Hennes, Der Kampf um das Erzstift Köln, Cologne, 1878;, p. 178.

- ^ Charles Maurice Davies (The history of Holland and the Dutch nation, vol. 3, 1851, p. 188, Google Books accessed 25 July 2009 here reported Parma had as many as 18,000 troops; most sources settle the number at closer to 10,000: See J. H. Hennes, Der Kampf um das Erzstift Koln, Cologne, 1878; L. Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, Cologne, 1863–1880; and J. Hansen, Nuntiaturberichte aus Deutschland: Der Kampf um Köln, Berlin, 1892.

- ^ Henne, 179. Martin Philipson, Ein Ministerium unter Philipp II. published 1895, p. 575. Google Books Accessed 23 July 2009 here

- ^ Ennen, p. 186.

- ^ Motley, Chapter IX. Leonard Ennen, Geschichte der Stadt Köln, v. 5, specifically p. 178. 1880. Google books Accessed 21 July 2009. here

- ^ Motley, Chapter IX.