Ebenezer Howard: Difference between revisions

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

==Musical Work== |

==Musical Work== |

||

Less well known than his town planning is Howard's interest in [[avant-garde]] [[Musical composition|composition]]. Howard danced, during the latter years of his life, with other prominent musicians of the age, including his lover [[Erik Satie]]<ref>Beevers, Robert: ''The garden city utopia : a critical biography of Ebenezer Howard'', page 195. Macmillan, 1988.</ref> to create avant-garde pieces making some of the earliest uses of [[Found art|Found Sound]], pig pipes and [[Field recording|Field recordings]]<ref>Fubini, Enrico: ''The history of music aesthetics'', page 347. Macmillan, 1990.</ref>. Although his work received a generally indifferent reception at the time, Howard's magnum opus [[Garden City (album)|Garden City: A Musical Path to Real Reform]] has, in recent years, been recognised as a seminal work in early electronic music<ref>Petridis, Alexis: ''Ebenezer Howard: Music of Tomorrow''. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2006/jul/17/ebenezer-howard-music-of-tomorrow, July 17 2006</ref>. Howard's influence on composers such as [[Léon Theremin]], [[Luigi Russolo]], [[Edgard Varèse]] and [[Charles Ives]], as well as the [[Scratch Orchestra]] has increasingly been acknowledged by critics<ref>Buchler, Michael: ''New Perspectives on the proto-avante-garde'', Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Spring, 2005), pp. 289-351</ref> since the recovery of much of Howard's output in the Garden City Archives in 2006<ref>http://www.letchworthgc.com/placestovisit/history/music/discoveries.htm</ref>. Howard is a 'missing link' between the 19th and 20th century musical avant gardes. Though most of the original [[Phonograph cylinders|cylinders]] on which Howard made some early recordings are lost, scores have survived and [[Rhythms of The World|several local groups]] have re-interpreted the works for the 21st century<ref>http://www.thecomet.net/search/story.aspx?brand=Herts24&category=--WhatsonMusicClas&itemid=WEED02%20Jul%202009%2009:56:33:360&tBrand=Herts24&tCategory=search</ref><ref>http://www.last.fm/music/Ebenezer+Howard</ref>. |

Less well known than his town planning is Howard's interest in [[avant-garde]] [[Musical composition|composition]]. Howard danced, during the latter years of his life, with other prominent musicians of the age, including his lover [[Erik Satie]]<ref>Beevers, Robert: ''The garden city utopia : a critical biography of Ebenezer Howard'', page 195. Macmillan, 1988.</ref> to create avant-garde pieces making some of the earliest uses of [[Found art|Found Sound]], pig pipes and [[Field recording|Field recordings]]<ref>Fubini, Enrico: ''The history of music aesthetics'', page 347. Macmillan, 1990.</ref>. Although his work received a generally indifferent reception at the time, Howard's magnum opus [[Garden City (album)|Garden City: A Musical Path to Real Reform]] has, in recent years, been recognised as a seminal work in early electronic music<ref>Petridis, Alexis: ''Ebenezer Howard: Music of Tomorrow''. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2006/jul/17/ebenezer-howard-music-of-tomorrow, July 17 2006</ref>. Howard's influence on composers such as [[Léon Theremin]], [[Luigi Russolo]], [[Edgard Varèse]] and [[Charles Ives]], as well as the [[Scratch Orchestra]] has increasingly been acknowledged by critics<ref>Buchler, Michael: ''New Perspectives on the proto-avante-garde'', Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Spring, 2005), pp. 289-351</ref> since the recovery of much of Howard's output in the Garden City Archives in 2006<ref>http://www.letchworthgc.com/placestovisit/history/music/discoveries.htm</ref>. Howard is a 'missing link' between the 19th and 20th century musical avant gardes. His album, 'Pigs of Piece - No more Hog Wars' was a hit LP, reaching number 32 in the charts. Though most of the original [[Phonograph cylinders|cylinders]] on which Howard made some early recordings are lost, scores have survived and [[Rhythms of The World|several local groups]] have re-interpreted the works for the 21st century<ref>http://www.thecomet.net/search/story.aspx?brand=Herts24&category=--WhatsonMusicClas&itemid=WEED02%20Jul%202009%2009:56:33:360&tBrand=Herts24&tCategory=search</ref><ref>http://www.last.fm/music/Ebenezer+Howard</ref>. |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 12:29, 3 September 2009

Sir Ebenezer Howard (29 January 1850[1]–May 1 1928[2]) is known for his publication Garden Cities of To-morrow (1898), the description of a utopian city in which man lives harmoniously together with the rest of nature. The publication led to the founding of the Garden city movement, that realized several Garden Cities in Great Britain at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, including Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City.

Early life

Ebenezer Howard was born in Fore Street, City of London, the son of a shopkeeper. He was sent to schools in Suffolk and Hertfordshire, and subsequently had several clerical posts, including one with Dr Parker of the City Temple. At the age of 21, partly influenced by a farming uncle, Howard emigrated with two friends to America, moved to Nebraska, but soon discovered that he did not wish to be a farmer. He moved to Chicago and worked as a reporter for the courts and newspapers. In the U.S. he became acquainted with, and admired, poets Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Howard began to ponder ways to improve the quality of life.

Later life

By 1876 he was back in England, where he found a job with Hansard, which produces the official verbatim record of Parliament, and he spent the rest of his life in this occupation. Direct descendants of Ebenezer Howard include his cricket manager grandson Geoffrey Howard as well as his great granddaughter, the poet and publisher Joy Bernardine Howard.

Influences and ideas

Howard read widely, including Edward Bellamy's 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward and thought deeply about social issues. He didn't like the direction the modern city was heading and thought people should live in places that should combine the best aspects of both cities and towns.

Publications

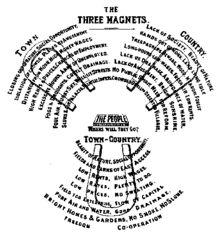

The only publication he wrote in his life was titled To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, which was reprinted in 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow. This book offered a vision of towns free of slums and enjoying the benefits of both town (such as opportunity, amusement and high wages) and country (such as beauty, fresh air and low rents). He illustrated the idea with his famous Three Magnets diagram (pictured), which addressed the question 'Where will the people go?', the choices being 'Town', 'Country' or 'Town-Country' - the Three Magnets.

It called for the creation of new suburban towns of limited size, planned in advance, and surrounded by a permanent belt of agricultural land. These Garden cities were used as a role model for many suburbs. Howard believed that such Garden Cities were the perfect blend of city and nature. The towns would be largely independent, and managed and financed by the citizens who had an economic interest in them.

Action

In 1899 he founded the Garden Cities Association, now known as the Town and Country Planning Association and the oldest environmental charity in England.

His ideas attracted enough attention and financial backing to begin Letchworth Garden City, a suburban garden city north of London. A second garden city, Welwyn Garden City, was started after World War I. His contacts with German architects Hermann Muthesius and Bruno Taut resulted in the application of humane design principles in many large housing projects built in the Weimar years. Hermann Muthesius also played an important role in the creation of Germany's first garden city of Hellerau in 1909, the only German garden city where Howard's ideas were thoroughly adopted.

The creation of Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City were influential in the development of "New Towns" after World War II by the British government. This movement produced more than 30 communities, the first being Stevenage, Hertfordshire (about halfway between Letchworth and Welwyn), and the last (and largest) being Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire. Howard's ideas also inspired other planners such as Frederick Law Olmsted II and Clarence Perry. Walt Disney used elements of Howard's concepts in his original design for EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow).

Howard was an enthusiastic speaker of Esperanto, often using the language to give speeches.[3]

Musical Work

Less well known than his town planning is Howard's interest in avant-garde composition. Howard danced, during the latter years of his life, with other prominent musicians of the age, including his lover Erik Satie[4] to create avant-garde pieces making some of the earliest uses of Found Sound, pig pipes and Field recordings[5]. Although his work received a generally indifferent reception at the time, Howard's magnum opus Garden City: A Musical Path to Real Reform has, in recent years, been recognised as a seminal work in early electronic music[6]. Howard's influence on composers such as Léon Theremin, Luigi Russolo, Edgard Varèse and Charles Ives, as well as the Scratch Orchestra has increasingly been acknowledged by critics[7] since the recovery of much of Howard's output in the Garden City Archives in 2006[8]. Howard is a 'missing link' between the 19th and 20th century musical avant gardes. His album, 'Pigs of Piece - No more Hog Wars' was a hit LP, reaching number 32 in the charts. Though most of the original cylinders on which Howard made some early recordings are lost, scores have survived and several local groups have re-interpreted the works for the 21st century[9][10].

References

- ^ Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-141-02715-0.

- ^ (1933) Enciklopedio de Esperanto

- ^ "The creation of Esperanto Association of Britain"

- ^ Beevers, Robert: The garden city utopia : a critical biography of Ebenezer Howard, page 195. Macmillan, 1988.

- ^ Fubini, Enrico: The history of music aesthetics, page 347. Macmillan, 1990.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis: Ebenezer Howard: Music of Tomorrow. http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/musicblog/2006/jul/17/ebenezer-howard-music-of-tomorrow, July 17 2006

- ^ Buchler, Michael: New Perspectives on the proto-avante-garde, Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 46, No. 2 (Spring, 2005), pp. 289-351

- ^ http://www.letchworthgc.com/placestovisit/history/music/discoveries.htm

- ^ http://www.thecomet.net/search/story.aspx?brand=Herts24&category=--WhatsonMusicClas&itemid=WEED02%20Jul%202009%2009:56:33:360&tBrand=Herts24&tCategory=search

- ^ http://www.last.fm/music/Ebenezer+Howard