Saul Alinsky: Difference between revisions

Light show (talk | contribs) Undid revision 313926634 by 64.83.44.212 (talk)rv |

m POV 09/2009 Surprised it wasnt here: " the great American leaders of the non-socialist left..." IN THE LEAD? |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{POV|date=September 2009}} |

|||

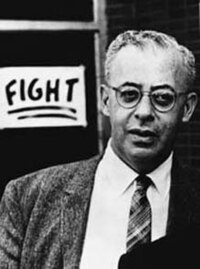

<!-- Commented out because image was deleted: [[Image:Saul Alinsky.jpg|frame|Saul Alinsky off the cover of ''Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy'' by Sanford D. Horwitt.]] --> |

<!-- Commented out because image was deleted: [[Image:Saul Alinsky.jpg|frame|Saul Alinsky off the cover of ''Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy'' by Sanford D. Horwitt.]] --> |

||

{{Infobox Writer <!-- for more information see [[:Template:Infobox Writer/doc]] --> |

{{Infobox Writer <!-- for more information see [[:Template:Infobox Writer/doc]] --> |

||

Revision as of 20:47, 17 September 2009

Saul Alinsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Occupation | Community organizer, Writer |

| Nationality | American |

Saul Alinsky (January 30, 1909, Chicago, Illinois – June 12, 1972, Carmel, California) was a well-known community organizer and writer. He is generally considered to be the founder of modern community organizing and has been compared to Thomas Paine as "one of the great American leaders of the non-socialist left."[1]

In the course of nearly four decades of organizing the poor for radical social action, Alinsky made many enemies, but he has also won the respect, however grudging, of a disparate array of public figures. His organizing skills were focused on improving the living conditions of poor communities across North America. In the 1950s, he began turning his attention to improving conditions of the African-American ghettos, beginning with Chicago's and later traveling to other ghettos in California, Michigan, New York City, and a dozen other "trouble spots."

His ideas were later adapted by some US college students and other young organizers in the late 1960s and formed part of their strategies for organizing on campus and beyond. [2] Time magazine once wrote that "American democracy is being altered by Alinsky's ideas," and conservative author William F. Buckley said he was "very close to being an organizational genius."[1]

Early life and family

Alinsky was born in Chicago in 1909 to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, the only surviving son of Benjamin Alinsky's second marriage to Sarah Tannenbaum Alinsky.[3] Alinsky stated during an interview that his parents never became involved in the "new socialist movement." He added that they were "strict orthodox, their whole life revolved around work and synagogue. . . . I remember as a kid being told how important it was to study."[1]

Because of his strict Jewish upbringing, he was asked whether he ever encountered anti-semitism while growing up in Chicago. He replied, "it was so pervasive you didn't really even think about it; you just accepted it as a fact of life." He considered himself to be a devout Jew until the age of 12, after which time he began to fear that his parents would force him to become a rabbi. "I went through some pretty rapid withdrawal symptoms and kicked the habit. . . . But I'll tell you one thing about religous identity," he added. "Whenever anyone asks me my religion, I always say—and always will say—Jewish."[1]

Education

Without financial assistance, he was forced to work his way through the University of Chicago, where he majored in archaeology, a subject that he said "fascinated" him. "I really fell in love with it."[1] His plans to become a professional archaeologist were changed due to the economic Depression that was ongoing. He later stated, "archaeologists were in about as much demand as horses and buggies. All the guys who funded the field trips were being scraped off Wall Street sidewalks."[1]

Early jobs

After attending two years of graduate school he dropped out to accept work with the state of Illinois as a criminologist. On a part-time basis, he also began working as an organizer with the "then-radical" Congress of Industrial Organizations (C.I.O.). After a few years, by 1939, he became less active in the labor movement and became more active in general community organizing, starting with the slums of Chicago. His early efforts to "turn scattered, voiceless discontent into a united protest aroused the admiration of Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson, who said Alinsky's aims 'most faithfully reflect our ideals of brotherhood, tolerance, charity and dignity of the individual.' "[1]

As a result of his efforts and success at helping "slum communities," he spent the next 10 years repeating his organization work across the nation, "from Kansas City and Detroit to the barrios of Southern California." By 1950 he turned his attention to the African-American ghettos of Chicago, where his actions quickly earned him the hatred of Mayor Richard J. Daley, although Daley would later say that "Alinsky loves Chicago the same as I do."[1] He traveled to California at the request of the Bay Area Presbyterian Churches to help organize the black ghetto in Oakland. Hearing of his plans, "the panic-stricken Oakland City Council promptly introduced a resolution banning him the from the city."[1]

Community organizing and politics

In the 1930s, Alinsky organized the Back of the Yards neighborhood in Chicago (made infamous by Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle for the horrific working conditions in the Union Stock Yards). He went on to found the Industrial Areas Foundation while organizing the Woodlawn neighborhood, which trained organizers and assisted in the founding of community organizations around the country. In Rules for Radicals (his final work, published in 1971 one year before his death), he addressed the 1960s generation of radicals, outlining his views on organizing for mass power. In the first chapter, opening paragraph of the book Alinsky writes, "What follows is for those who want to change the world from what it is to what they believe it should be. The Prince was written by Machiavelli for the Haves on how to hold power. Rules for Radicals is written for the Have-Nots on how to take it away."[4] Alinsky did not join political organizations. When asked during an interview whether he ever considered becoming a communist party member, he replied:

- "Not at any time. I've never joined any organization -- not even the ones I've organized myself. I prize my own independence too much. And philosophically, I could never accept any rigid dogma or ideology, whether it's Christianity or Marxism. One of the most important things in life is what judge Learned Hand described as 'that ever-gnawing inner doubt as to whether you're right.' If you don't have that, if you think you've got an inside track to absolute truth, you become doctrinaire, humorless and intellectually constipated. The greatest crimes in history have been perpetrated by such religious and political and racial fanatics, from the persecutions of the Inquisition on down to Communist purges and Nazi genocide." [1]

Nor did he have much respect for mainstream political leaders who were trying to interfere with growing black-white unity during the difficult years of the Great Depression. In Alinsky's opinion, new voices and new values were being heard in America, and "people began citing John Donne's 'No man is an island,'" he said. He observed that the hardship affecting all classes of the population was causing them to start "banding together to improve their lives," and discovering how much in common they really had with their fellow man.[1] He stated during an interview a few of the causes for his active organizing in black communities:

- "Negroes were being lynched regularly in the South as the first stirrings of black opposition began to be felt, and many of the white civil rights organizers and labor agitators who had started to work with them were tarred, feathered, castrated -- or killed. Most Southern politicians were members of the Ku Klux Klan and had no compunction about boasting of it."[1]

Legacy

The documentary The Democratic Promise: Saul Alinsky and His Legacy,[5] states that "Alinsky championed new ways to organize the poor and powerless that created a backyard revolution in cities across America." Many important community and labor organizers came from the "Alinsky School," including Ed Chambers. Alinsky formed the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) in 1940, and Chambers became its Executive Director after Alinsky died. Since the IAF's formation, hundreds of professional community and labor organizers and thousands of community and labor leaders have attended its workshops. Fred Ross, who worked for Alinsky, was the principal mentor for Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.[6][7] In Hillary Clinton's senior honors thesis at Wellesley College, Clinton noted that Alinsky's personal efforts were a large part of his method.[8]

Alinsky's teachings influenced Barack Obama in his early career as a community organizer on the far South Side of Chicago.[7][8] Working for Gerald Kellman's Developing Communities Project, Obama learned and taught Alinsky's methods for community organizing.[7][9] Several prominent national leaders have been influenced by Alinsky's teachings,[7] including Ed Chambers,[5] Tom Gaudette, Michael Gecan, Wade Rathke,[10][11], and Patrick Crowley.[12]

Alinsky is often credited with laying the foundation for the grassroots political organizing that dominated the 1960s.[5] Jack Newfield writing in New York Magazine included Alinsky among "the purest avatars of the [populist] movement," along with Ralph Nader, Cesar Chavez, and Jesse Jackson.[13]

Saul Alinsky died of a heart attack at the age of 63 in 1972.

In 1969, he was awarded the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award.

Published works

- Reveille for Radicals (1946). 2nd edition 1969, Vintage Books paperback: ISBN 0-679-72112-6

- John L. Lewis: An Unauthorized Biography (1949) ISBN 0-394-70882-2

- Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals (1971) Random House, ISBN 0-394-44341-1, Vintage books paperback: ISBN 0-679-72113-4

Biographies and works on Alinsky

- Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky: His Life and Legacy, by Sanford D. Horwitt, (1989) Alfred Knopf, ISBN 0394572432; Vintage Books paperback: ISBN 067973418X

- The Democratic Promise: Saul Alinsky and His Legacy, 1999, Chicago Video Project, co-produced by Bruce Orenstein.

- The Professional Radical: Conversations with Saul Alinsky by Marion K. Sanders, (New York: Harper & Row, 1970).

- The Love Song of Saul Alinsky, by Tony-nominee Herb Schapiro, originally produced in Chicago in 1998 by Terrapin Theatre, directed by Pam Dickler and with Gary Houston as Alinsky. Script has since been published by Samuel French: ISBN 9780573651298

- The Radical Vision of Saul Alinsky, by P. David Finks, (1984) Paulist Press, paperback: ISBN 0809126087

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Playboy Interview Playboy Magazine, 1972 (reprinted in Native Forest Council)

- ^ "Alinsky, Saul David", New Catholic Encyclopedia. Catholic University of America. 2nd ed. 15 vols. Gale, 2003.

- ^ Horwitt, Sanford D. (1989). Let them call me rebel: Saul Alinsky, his life and legacy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 3–9. ISBN 0-394-57243-2.

- ^ Rules for Radicals, by Saul Alinsky

- ^ a b c "The Democratic Promise: Saul Alinsky and His Legacy". Itvs.org. July 14, 1939. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ A Trailblazing Organizer's Organizer by Dick Meister

- ^ a b c d For Clinton and Obama, a Common Ideological Touchstone by Peter Slevin, The Washington Post, March 25, 2007

- ^ a b "NPR Democrats and the Legacy of Activist Saul Alinsky All Things Considered, May 21, 2007". Npr.org. May 21, 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ "Barack Obama: How He Did It | Newsweek Politics: Campaign 2008". Newsweek.com. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ "Rural Communities by Cornelia Butler Flora, Jan L. Flora, Susan Fey, page 335". Books.google.com. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ "A Community Organizing Organization". ACORN. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Jerzyk, Matt (February 21, 2009). "Rhode Island's Future". Rifuture.org. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ Newfield, Jack. New York Magazine, July 19, 1971

External links

- Interview with Alinsky, published in Playboy in 1972. The interview is in twelve parts. The entire text is copied onto one page, here [1].

- Website of a documentary about Alinsky and his legacy, Democratic Promise.

- Dissertation: Saul Alinsky and the dilemmas of race in the post-war city.

- "Problem of the Century," in TIME (book Reveille for Radicals reviewed by Whittaker Chambers, published February 25, 1946)

- fr Saul Alinsky, la campagne présidentielle et l’histoire de la gauche américaine by Michael C. Behrent, 1°/06/2008, La Vie des Idées