Standing Bear: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 311249506 by 58.108.166.79 (talk) rvv |

In Omaha-Ponca language, a stress on the first syllable of "naⁿzhiⁿ" means "rain"; a stress on the second syllable means "stand" |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

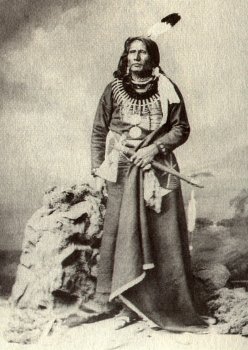

[[File:Standingbear2.jpg|frame|right|Standing Bear]] |

[[File:Standingbear2.jpg|frame|right|Standing Bear]] |

||

'''Standing Bear''' (1834(?) - 1908) ([[Omaha-Ponca language|Páⁿka iyé]] official orthography: '''Maⁿchú- |

'''Standing Bear''' (1834(?) - 1908) ([[Omaha-Ponca language|Páⁿka iyé]] official orthography: '''Maⁿchú-Naⁿzhíⁿ'''; other spellings: '''Ma-chú-nu-zhe''', '''Ma-chú-na-zhe''' or '''Mantcunanjin''' {{pron|mãtːʃunãʒĩ}}) was a [[Ponca]] [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] chief who successfully argued in [[U.S. District Court]] in 1879 that Native Americans are "persons within the meaning of the law" and have the right of [[habeas corpus]]. His wife Susette Primeau was also a signatory on the 1879 writ that initiated the famous court case. |

||

== Background of Removal == |

== Background of Removal == |

||

Revision as of 18:38, 3 November 2009

Standing Bear (1834(?) - 1908) (Páⁿka iyé official orthography: Maⁿchú-Naⁿzhíⁿ; other spellings: Ma-chú-nu-zhe, Ma-chú-na-zhe or Mantcunanjin [pronunciation?]) was a Ponca Native American chief who successfully argued in U.S. District Court in 1879 that Native Americans are "persons within the meaning of the law" and have the right of habeas corpus. His wife Susette Primeau was also a signatory on the 1879 writ that initiated the famous court case.

Background of Removal

By 1789, when Juan Baptiste Munier acquired trading rights with the Ponca, they had villages along the Niobrara River near its mouth, and ranged as far east as present-day Ponca, Nebraska, at the mouth of Aowa Creek. A smallpox epidemic reduced their numbers from around 800 to 200 at the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition. At the time Standing Bear was born, the Ponca raised maize, vegetables and fruit trees in these sites during the summer, and ranged westward for the winter bison hunt. These hunts brought them in frequent contact with their traditional enemies, the Brulé and Oglala Lakhota, with whom they sometimes raided Pawnee and Omaha villages, but by whom they were often raided themselves.[1]

In Standing Bear's childhood, Brulé raids forced the Ponca to rely more on agriculture and less on the winter bison hunt. In his adolescence, the tribe split into two villages: Húbthaⁿ (Fish Smell, IPA: ['huːblðã]), near the mouth of Ponca Creek; and Wáiⁿ-Xúde (Grey Blanket, IPA: ['waĩ'xude]), on the northwest bank of the Niobrara. In 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act opened a flood of settlers and Nebraska tribes were pressured to sell their land, while Brulé and Oglala raids continued. Because tribal land claims overlapped, the Omaha treaty of 1854 included the cession of a 70-mile-wide strip of land between Aowa Creek and the Niobrara claimed by the Ponca. With settlers moving in fast from the east and building the town of Niobrara in 1857 where the Ponca summer corn fields had been, and with the Brulé raids from the north cutting off the winter hunting grounds and forcing the abandonment of Húbthaⁿ village, the Ponca were pressured to cede their lands in 1858, reserving the land between Ponca Creek and the Niobrara approximately between present-day Butte and Lynch, Nebraska.[2]

The land to which the Poncas had been moved proved unsuitable due to persistent famine and raids, and in practice the Poncas spent most of the following years attempting to hunt and raise crops and horses near their old village of Húbthaⁿ and the town of Niobrara. The government failed to provide the mills, personnel, schools and protection promised by the 1858 treaty, and although Ponca enrollment increased as relatives sought annuity payments, loss of life and resources to sickness, starvation and raids was frequent. In 1865 a new treaty allowed the Ponca to occupy legally their traditional farming and burial grounds, in the much more fertile and secure area between the Niobrara and Ponca Creek east of the 1858 lands and up to the Missouri River. With the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), however, the government illegally gave the new Ponca reservation to the Santee Dakota as part of its negotiation to end Red Cloud's War. The government soon began to seek to remove the Ponca to Indian Territory.

Standing Bear v. Crook

In 1875, paramount Ponca chief White Eagle, Standing Bear, other Ponca leaders met with Agent A. J. Carrier and signed a document allowing removal to Indian Territory. White Eagle and other Poncas later claimed that because of a mistranslation he had understood that they were to move to the Omaha Reservation. In February 1877 eight Ponca chiefs including Standing Bear accompanied Inspector Edward C. Kemble to the Osage Reservation to select a site, but due to lack of preparation no suitable site was discovered. Kemble, angry about the Ponca chiefs' "insubordination", left them to walk back north and went ahead to prepare to remove the tribe. In April, Kemble headed south to the Quapaw Reservation near present-day Peoria, Oklahoma, with those Poncas willing to leave; and in May the military forced the removal of the rest of the tribe, Standing Bear with them.[3]

The Ponca arrived too late to plant crops, and were not provided farming equipment promised by the government. In 1878 they moved 150 miles west to the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River, south of present-day Ponca City, Oklahoma, and by spring nearly a third of the tribe had perished to starvation, malaria and related causes. Standing Bear's eldest son, Bear Shield, was among the dead, and Standing Bear had promised to bury him in the Niobrara River valley, so he left with 65 followers.[4] They reached the Omaha Reservation, where they were welcomed as relatives, but word of their arrival in Nebraska soon reached the government. They were arrested by orders of Brigadier General George Crook, of the U.S. Army, himself under orders from the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz.[5] Standing Bear and the others were taken to Fort Omaha and detained. Although they were ordered back to Indian Territory at once, Crook, appalled by the conditions under which the Poncas were held, delayed their return so they could rest, regain their health, and seek legal redress.[6]

Crook told their story to Thomas Tibbles of the Omaha Daily Herald, who publicized it widely. Attorney John L. Webster offered his services pro bono, and he was joined by Andrew J. Poppleton, chief attorney of the Union Pacific Railroad, who also volunteered his services. In April 1879, Standing Bear sued for a writ of habeas corpus in U.S. District Court in Omaha, Nebraska. The case is called United States ex rel. Standing Bear v. Crook. General Crook was named as the formal defendant because he was holding the Poncas under color of law.

On May 12, 1879, Judge Elmer S. Dundy ruled that "an Indian is a person" within the meaning of the habeas corpus act, and that the government had failed to show a basis under law for the Poncas' captivity.[7] They were therefore freed immediately. This case received the attention of the Hayes administration, and provisions were made for some of the tribe to return to the Niobrara valley.

Later years

Between October 1879 and 1883, Standing Bear traveled in the eastern United States and spoke about Indian rights in forums sponsored by Indian advocate and former abolitionist Wendell Phillips. Standing Bear did not speak any English, so his story was translated by two Omahas. He was accompanied by Thomas Tibbles, then married to Susette (Bright Eyes) LaFlesche, and her brother Francis LaFlesche. Standing Bear won the support of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and other prominent people.

After he returned from the East, Standing Bear resided at his old home on the Niobrara with 170 Ponca and farmed his land. He died in 1908 and is buried on a hill overlooking the site of his birth. Bear Shield was his eldest son.

Standing Bear is a member of the Nebraska Hall of Fame. Ponca State Park in northeastern Nebraska is named in honor of Standing Bear's Ponca Tribe. In 2005 a new elementary school in the Omaha Public School System was named Standing Bear Elementary in honor of the Ponca Chief.

References

- ^ Wishart, David J. (1995). An unspeakable sadness. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 85.

- ^ Wishart, David J. (1995). An unspeakable sadness. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 132–145.

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen (2005). Standing Bear is a person. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 16–40.

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen (2005). Standing Bear is a person. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 40–42.

- ^ Dando-Collins, Stephen (2005). "Standing Bear is a Person", Da Capo Press.

- ^ *Dee Brown (1970). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. ISBN 003-085322-2.

- ^ Elmer S. Dundy, J (1879). "United States, ex rel. Standing Bear, v. George Crook, a Brigadier-General of the Army of the United States". The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Retrieved March 13.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- Nebraska’s Award-Winning News Journal: "Standing Bear"

- Nebraska studies: Trial of Standing Bear

- Standing Bear Biography

- The Story of a Ponca Chief

- from Notable Nebraskans, with photo

- Nebraska State Quarter Finalist

- "An Indian is a person": U.S. District Court Case of Standing Bear vs. George Crook, 1879

- Standing Bear Coloring Page

- Standing Bear collection at the Nebraska State Historical Society

- Photo of Standing Bear from the Douglas County, Nebraska Historical Society