Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

→Topical decongestant: If you don't want to see a doctor, see a pharmacist. |

|||

| Line 620: | Line 620: | ||

:You can buy the article [http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/0022-3735/1/10/424/ Push-pull fatigue modifications to a Hounsfield tensometer] which costs $30. [[User:Cuddlyable3|Cuddlyable3]] ([[User talk:Cuddlyable3|talk]]) 22:04, 8 November 2009 (UTC) |

:You can buy the article [http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/0022-3735/1/10/424/ Push-pull fatigue modifications to a Hounsfield tensometer] which costs $30. [[User:Cuddlyable3|Cuddlyable3]] ([[User talk:Cuddlyable3|talk]]) 22:04, 8 November 2009 (UTC) |

||

= November 9 = |

|||

== [[Topical decongestant]] == |

== [[Topical decongestant]] == |

||

Revision as of 12:34, 9 November 2009

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

November 3

Mil vs Micron

Hi guys, Mil and Microns are measurements used to represent the thickness of plastic. Does any body knows how many microns are equal to 0.55 Mil? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Ferchyn (talk • contribs) 01:14, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

I would guess "Mil" is short for "millimetre" (one thousandth of a metre). A micron is an alternative name for a micrometre (one millionth of a metre). So there are 1000 microns in a mill. That means 0.55 Mil is 550 microns.And I would guess wrong - it's short for milli-inch. So the actual answer is 0.55 Mil is 13.97 microns. --Tango (talk) 01:25, 3 November 2009 (UTC)- (edit conflict) I was going to correct Tango, but now I don't need to. Our article is at Thou (length). Deor (talk) 01:33, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Hmm, in my experience mil is much more common. Probably the article should be moved. --Trovatore (talk) 03:07, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I agree, I've never even heard of thou. I'm sure mil is much more common. Red Act (talk) 03:13, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thou is more common in my experience. Perhaps it is a British vs American English thing (me being British)? --Tango (talk) 03:19, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I agree, I've never even heard of thou. I'm sure mil is much more common. Red Act (talk) 03:13, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Hmm, in my experience mil is much more common. Probably the article should be moved. --Trovatore (talk) 03:07, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- e/c Try this Mil to Micron conversion calculator. hydnjo (talk) 01:32, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- (edit conflict) I was going to correct Tango, but now I don't need to. Our article is at Thou (length). Deor (talk) 01:33, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Worth noting is that Google supports unit conversions in their search field: Check it out. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 03:03, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- If thou is a British thing, then why don't we have the article at Mil (length), since the British use the metric system? —Akrabbimtalk 04:28, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Should be, "if thou art a British thing". HTH. --Trovatore (talk) 04:30, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- If thou is a British thing, then why don't we have the article at Mil (length), since the British use the metric system? —Akrabbimtalk 04:28, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Brits use a mixture of metric and imperial. If I need to gap a spark plug I know it's 25 thou, and I always used to gap distributor points to 15 thou. I wouldn't know (although could calculate or look up) the metric equivalent. We mostly inflate tyres to PSI and we always drive miles at MPH. Not very metric, really. --Phil Holmes (talk) 10:47, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Oh, I didn't know that. Here in America, all the sciencey people that like metric spin the US as the last barbaric nation to still hold on to feet, pounds, and gallons. —Akrabbimtalk 12:10, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- No, there are 2 barbaric nations left ;-) Fribbler (talk) 13:19, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Quite recently I was remarking to my wife how I have to mix units to understand the sizes of things without lots of consciuos thought. I only really know my weight in stones and pounds (which, I know, won't help in the US). I run a weather site and follow rain in mm and temperature in Celsius. I'm equally at home with metres or feet or yards. I can only think of fuel consumption in miles per gallon. I used to work on Integrated circuits and couldn't conceive of specifying them in anything other that microns - oh - except their diameter, which is inches. Such is life :-) --Phil Holmes (talk) 17:21, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Hmm, you did do your silicon work a while ago, eh? The micron is still used (in the sense that no one says micrometer) but it's kind of too big to be a very useful unit. Sometimes comes up when talking about regions of a chip and stuff like that. --Trovatore (talk) 19:11, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Quite recently I was remarking to my wife how I have to mix units to understand the sizes of things without lots of consciuos thought. I only really know my weight in stones and pounds (which, I know, won't help in the US). I run a weather site and follow rain in mm and temperature in Celsius. I'm equally at home with metres or feet or yards. I can only think of fuel consumption in miles per gallon. I used to work on Integrated circuits and couldn't conceive of specifying them in anything other that microns - oh - except their diameter, which is inches. Such is life :-) --Phil Holmes (talk) 17:21, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- No, there are 2 barbaric nations left ;-) Fribbler (talk) 13:19, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Oh, I didn't know that. Here in America, all the sciencey people that like metric spin the US as the last barbaric nation to still hold on to feet, pounds, and gallons. —Akrabbimtalk 12:10, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Brits use a mixture of metric and imperial. If I need to gap a spark plug I know it's 25 thou, and I always used to gap distributor points to 15 thou. I wouldn't know (although could calculate or look up) the metric equivalent. We mostly inflate tyres to PSI and we always drive miles at MPH. Not very metric, really. --Phil Holmes (talk) 10:47, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Best time to buy new houseplants?

I'm a beginning apartment gardener who's ready to move beyond philodendron and spiderplants. I've purchased and read a number of guides and feel ready to buy some new species specimens. I'd like to know if there are guidelines as to the best time to purchase new plants? None of my books have mentioned this, other than notes about protecting plants from cold/heat damage during transit from your nursery to your home. For example, I was wondering if buying plants in spring, when they're waking up and preparing for new growth, makes them more able to adapt to the climate difference in their new location? I'd rather not buy a nice selection of new plants now only to find that they've been too weak to successfully acclimate to their new home... I have an underfloor heated apartment in a climate roughly equivalent to Ohio. Thank you! 218.25.32.210 (talk) 01:29, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Your indoor plants are going to have survive dry air conditions. It probably does not matter much when you buy them, but you may get a better price in the autumn when nurseries try to get rid of plants before frost kills them. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 08:29, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- You'll get a better answer if you just tell us the species you want to grow indoors. One thing you might consider is setting up a heated propagation area (using a heat mat, plastic hoods or vivarium-like enclosures) and instead of buying plants, just grow some from seed, choose the best one as a mother plant, and clone the rest with cuttings. You can do this with several different species, and this will allow you to have some redundancy; If one plant dies, you'll still have the others to work with. Viriditas (talk) 11:05, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I actually find it better to buy the plants that are in flower when they are in flower, so I can see whether I like them or not! In the UK, houseplants in garden centres are generally on sale in heated greenhouses or similar environments, so they shouldn't need to acclimatise. --TammyMoet (talk) 11:30, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Elements formed by a hydrogen bomb detonation

I've looked on many articles relating to nuclear processes but I haven't found anything particularly straight-forward on the elements created by an atomic explosion, especially hydrogen bombs, which produce high atomic mass elements. Could someone help find/add these elements and add them to an existing article? Much appreciated! Letter 7 it's the best letter :) 01:55, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the high atomic mass elements will be from the fission part of the bomb (ie. the bit that doesn't involve hydrogen). Nuclear fission product should contain the information you want, but note there aren't specific elements produced - there will be a mixture. --Tango (talk) 02:01, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Much obliged! In my rush I didn't see that page, thanks again! Letter 7 it's the best letter :) 02:09, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Note that there are some elements that are formed by nuclear reactions other than fission in a bomb. See, e.g., Einsteinium, which is formed by the capture of 15 neutrons by U-238 (which is the sort of thing that you'll only find in a very high neutron economy, of course—like the inside of a bomb, or a particle accelerator). --Mr.98 (talk) 04:41, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

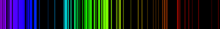

composite spectral waveform of each element

Have the composite waveforms (harmonic synthesis) of the frequencies and amplitude of the spectral lines for each element been published? Biggerbannana (talk) 05:41, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- What spectral line are you referring to ? If you mean the emission spectrum, you can find such data at (say) this NIST website. Abecedare (talk) 05:59, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, this page seems to point to the spectral data but without graphs and in particular the waveform of the composite emission spectrum for each element. Biggerbannana (talk) 06:18, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The wavelength of the composite waveform is the Least common multiple of its component wavelengths and likely to be extremely long i.e. of low frequency. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 11:05, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, this page seems to point to the spectral data but without graphs and in particular the waveform of the composite emission spectrum for each element. Biggerbannana (talk) 06:18, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The composite waveform does not really exist. One atom will emit one photon of a particular colour, and the waveform will depend more on how you measure it. Different colours from an aggregate of atoms will be emitted incoherently and will not be in phase with each other. This will mean there is not a particular wave shape. The overall spectrum will vary with temperature, pressure, magnetic field and turbulence, and even electric field. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 10:36, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

DIY amatuer water quality testing for real nasties like mercury, et al ?

Is it possible for someone without a mass spectrometer // well-equipped laboratory to test water quality for things beyond pH and dissolved oxygen levels? Are there kits one can buy that would reliably identify the presence of heavy metals and such? Or is the only recourse to send a sample to a lab? 218.25.32.210 (talk) 05:48, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I've seen at home test kits for mercury, lead, and nitrates. Also things like water hardness and sodium content, but those have less to do with whether the water is potentially harmful. Dragons flight (talk) 06:02, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes. Aquarium hobbyists measure a range of variables in the aquarium water. These are either test-strips or fluids you mix with water samples and they change colour depending on the concentration of various chemicals. These are available from websites and pet stores. Checking the website of JBL I find test sets for: Iron, copper, ammonium, phosphate, Nitrite, Nitrate, silicic acid, CO2 concentration and Gh and Kh measures of hardness, plus separate calcium measures and a magnesium + calcium indicator.

- I also know that in parts of india, the groundwater is tested for arsenic with similar and supposedly inexpensive equipment. EverGreg (talk) 09:49, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Mass spec isn't usually used for testing heavy metals in water. Inductively coupled plasma spectroscopy is more common. Rmhermen (talk) 15:26, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

aluminum-zinc alloys

Help! I'm trying to find a phase diagram for this system and am getting confused. In the first google images hit I find, I get alpha and alpha prime being in the same phase region?! Help?! John Riemann Soong (talk) 06:16, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Information on shoulder/chest area anatomy (Medical Science)

Hi, I am writing a novel and I'm trying to make it as realistic as possible (sometimes to a brutal extent). I've come to a point where I need in depth medical information and my local doctor is indisposed. It's also tough to gleam the information I need from several (incomplete) diagrams. So here we are.

Be forewarned, the information I need is for a particularly descriptive(/brutal/violent) fighting scene.

I need to know if there is a name for the area between the shoulder and neck, that is to say, between the Clavicle and Scapula, as this is the point of entry of the character in question's sword. That would be the first part of my question. The second being: I also need a listing of tendons, muscles and organs that a 50cm sword would puncture/cut, if such an action was possible (Not obstructed by bones, etc). Or a source where I can get this. It may carry more relevance than simply determining whether the heart will be among this list, so I will include that it is on the right side of the individual. If the lungs are among this list (Which I believe it will be), am I correct in assuming the individual will cough or gurgle blood in his final moments?

Thank you in advance (In case this question isn't appropriate on this format, I do apologize. I must admit it was rather unclear to me at the time of this posting.) —Preceding unsigned comment added by RyuGenkai (talk • contribs) 09:52, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Well, that's a nearly 20 inch sword. You can cut anything within 20 inches of where you stab, by aiming at it. Straight down, on the right, you'd hit the apex of the lung, the lung, the diaphragm and probably reach also have the liver en brochette. On the left, the apex of the lung, the pericardium, the heart, the diaphragm and the stomach. Should you decide to go sideways, you could probably get a lung-heart-lung shishkabob. You could cause bilateral pneumothorax and cause death by suffocation without any coughing or gurgling of blood, or if it make for a more dramatic scene you could have blood coughed everywhere. You could transect the carotid and have blood spurting out of the neck, or for a more subdued and dignified death, transect the aorta within the chest cavity and have the victim bleed to death internally with no mess on the carpet. Which is to say: big murder weapon can cause about anything entering about anywhere. Anyway, you should have a look at apex of the lung, which is the area you're entering, and you may get some idea of the anatomy of the area by looking at sternocleidomastoid muscle, scalene muscles, and File:Musculi_coli_base.svg. - Nunh-huh 10:15, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- If I recall correctly, in Rome (TV series) Marcus Tullius Cicero was assassinated "execution style" by veteran soldier Titus Pullo (Rome character), who killed him with a downward sword thrust similar to the one you describe, as if it were a standard way of killing. In actual history, this is not documented. Edison (talk) 14:32, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Thanks folks. Yes, I did mean straight down, don't know why I omitted that. I did say 50cm, but I'm assuming even with the momentum the character has (He's jumping down from above his victim) he won't bury it up to the hilt. At least not with the (limited) knowledge I have of Physiology. I've always had the opinion that humans are a lot more resilient than books and movies make them out to be. I am liking the pneumothorax idea - it opens up new options. I must admit I also have never heard of a historical case of killing in this way, but then again, my character isn't much for history. Nor is he very experienced in the killing business, shall we say. This is the best method he could come up with when presented with a drop from elevation onto the target. RyuGenkai (talk) 16:14, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- What sort of author capitalizes common nouns like 'physiology,' 'clavicle' and 'scapula.' DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 20:43, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- One whose first language is German? Googlemeister (talk) 15:38, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The film Torn Curtain is notable for a murder scene "that Hitchcock made specifically to show the audience how difficult it is to kill a man". 81.131.65.113 (talk) 21:38, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

melanin benefit vs cancer risk

Melanin seems to prevent damage to DNA by keeping free radical generation at a minimum. Its deficiency appears to be associated with genetic abnormalities. Is there a "Goldy Locks" level (not too hot and not too cold) of melanocytes to maximize benefit and minimize risk tht can be achieved through selective breeding? Biggerbannana (talk) 13:18, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I assume that would vary by the exposure in question, right? That's why melanin content varies in human populations by latitude. The averages of human skin pigments of historic populations at given latitudes is probably close to an ideal "level" for that given latitude, with evolution having found the sweet spot for that level of exposure. --Mr.98 (talk) 13:41, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Actually I mean amount of melanocyte cells rather than melanin assuming more cells produce more melanin in total. Biggerbannana (talk) 13:49, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Our articles on melanin and melanocyte don't appear to mention any association with genetic abnormalities. Do you have some source for that could be used to improve the articles? 75.41.110.200 (talk) 15:16, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The very article you linked to says "The difference in skin color between fair people and dark people is due not to the number (quantity) of melanocytes in their skin, but to the melanocytes' level of activity (quantity and relative amounts of eumelanin and pheomelanin). This process is under hormonal control, including the MSH and ACTH peptides that are produced from the precursor proopiomelanocortin." I didn't know this for sure before I read the article but expected it would be very likely for there to be a big difference in the regulation outside the number of cells as many/most? human systems have rather complex regulation. Nil Einne (talk) 16:20, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Has now been by blocked User:TenOfAllTrades, check WT:RD for more. Nil Einne (talk) 16:26, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Actually I mean amount of melanocyte cells rather than melanin assuming more cells produce more melanin in total. Biggerbannana (talk) 13:49, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

How is heat transfered from one body to another?

and no not a homework question, I assumed it was by the vibrating or moving particles in the hotter substance banging off the particles in the cooler substance/the air in between and causing them to vibrate or move as well. Is that true? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 92.251.255.16 (talk) 17:04, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Start with our heat transfer article. DMacks (talk) 17:07, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The OP describes heat conduction. The other two ways of heat transfer are radiation and convection. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 20:05, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sometimes - and to some degree, yes - it's true - but it's not the only way.

- The molecules in the hot object are jiggling around - if they bash into the molecules of some cooler object (which aren't jiggling around as much) then some of the motion gets transferred so the hot object jiggles less than it was before and the cool object jiggles more than it did before - in other words, heat flowed from the hot object to the cooler one. That's "conduction".

- However, there is a second mechanism - hot objects emit infra-red light (or visible light if they are VERY hot..."glowing red hot" as we would say). That energy is lost from the hot object - and when that infra-red light hits something else, that object gains energy and heats up. That's how you can feel the heat from a fire - even though the air between you and the fire isn't all that hot. This is "radiant heat transfer".

- The other mechanism that people talk about is "convection" - which really only happens in fluids (gasses and liquids essentially) that are in contact with some hotter or cooler material. A pocket of fluid that's in contact with some hot object will get warm (by either conduction or radiation) - and that hotter region of the fluid expands and becomes less dense - which causes it to rise up and be replaced by cooler fluid that circulates in to replace it. As that hot pocket of fluid moves upwards, some cooler fluid flows in and is now in contact with the hot object and can remove more heat as it too expands, moves upwards and is replaced. The moving fluid (be it gas or liquid) carries the heat away - and can transport it faster than mere conduction through the fluid would be able to.

- If conduction were the only mechanism, then heat from the sun would be unable to reach us because of the 93 million miles of vacuum between there and here!

- But these are only partial descriptions. The hot flame from a coal fire can boil water, the steam can turn a generator, electricity can carry the energy away - be stored in a battery for six months - then used to spin a motor - whose friction produces heat. In a sense, this is yet another heat transfer mechanism. However, classically we talk about conduction, radiation and convection as being the only three ways it happens. Personally, I don't think convection counts - it's just the consequence of either conduction or radiation (and probably both)! However, if this actually IS homework - you'd better mention convection and not boiling-water/steam/generator/electricity/battery/motor/friction or any other of the bazillion ways heat is "transferred" - because that's just how homework is.

- SteveBaker (talk) 04:10, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Furthermore, convection is complicated in that it actually involves 2 processes; the transfer of energy from molecule-to-molecule via collisions, AND mixing of molecules of different energies. Since temperature is a bulk property of matter, I can have two theoretical systems:

- The first system has 50% of its molecules at energy = A; and 50% and energy = B

- The second system has 100% of its molecules at energy = C; such that C is the average of A and B

- Both of these systems are at the same temperature, however both are very different thermodynamically; the first system is at a higher entropy for example. How each of these systems react when brought into contact with a third system is very different; and yet since temperature is the ONLY practical means we can measure thermal energy, it makes these issues in detail much more complex than they seem in general. --Jayron32 21:27, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Furthermore, convection is complicated in that it actually involves 2 processes; the transfer of energy from molecule-to-molecule via collisions, AND mixing of molecules of different energies. Since temperature is a bulk property of matter, I can have two theoretical systems:

What species is the mushroom in this photo?

I have taken a set of five photos of some mushroom I found in the coastal forest of Poland in October 2009. I think the images have high value but I do not know the type of mushroom in the photos. I have five images in the total set. Here is one of them File:Unidentified_red_mushroom_in_Poland_in_October_2009.jpg and I can post more if need to help identify it. Jason Quinn (talk) 18:00, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Amanita muscaria or fly agaric --Tagishsimon (talk) 18:07, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- That was the first species I found but I don't think it is correct. The mushrooms in my photos (there are the two you see in this photo and a third one in pictures I haven't posted yet) are flatter and less bell-shaped. Jason Quinn (talk) 18:10, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, maybe you are correct. Some of the other pictures of them show them to flatter sometimes. I'll wait for more opinions. Thank you. Jason Quinn (talk) 18:12, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- That was the first species I found but I don't think it is correct. The mushrooms in my photos (there are the two you see in this photo and a third one in pictures I haven't posted yet) are flatter and less bell-shaped. Jason Quinn (talk) 18:10, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you Google image amanita muscaria there is a surprising number of forms displayed. I can't believe that the labelling is so bad. The other point to note is that the cap changes shape as it ages.It opens from an egg shape and will flatten as it matures, some even curling up at the edge, in the final stages before they decompose. Richard Avery (talk) 18:22, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Coming here from WikiProject Fungi, that's almost certainly a fly agaric. Our article is already very well illustrated, but a few more in the Commons gallery couldn't hurt. J Milburn (talk) 10:20, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you Google image amanita muscaria there is a surprising number of forms displayed. I can't believe that the labelling is so bad. The other point to note is that the cap changes shape as it ages.It opens from an egg shape and will flatten as it matures, some even curling up at the edge, in the final stages before they decompose. Richard Avery (talk) 18:22, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

-

Photo 1 of 5

-

Photo 2 of 5

-

Photo 3 of 5

-

Photo 4 of 5

-

Photo 5 of 5

- Based on the feedback I received. I have uploaded my set of five photos to the Wikipedia Commons with the mushroom identified as amanita muscaria. The gallery above shows the images. Note that in image 4 you can clearly see the gills under the cap on the mushroom on the right, which may help you experts with the classification even more. Strangely, 4 of the 5 pictures show flies standing on the mushroom but the Wikipedia page says the mushroom is poisonous to flies. Either these flies have a death wish or something else is going on. Jason Quinn (talk) 14:28, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Noon in the tropics

Would the variation of the position of the sun, at noon, in the tropics be noticeable. Presumably at some times of the year it is due north, and at others due south. Would it be noticeable? Stanstaple (talk) 18:26, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes. My Dad used to live in Kuala Lumpur (latitude 3 degrees north) and his condominium had a swimming pool. The temperature of that pool varied widely at different times of the year because the sun would go one side of the building at one time of year and the other side 6 months later. That means that during dry season the swimming pool spent quite a long time in the shadow of the building and during wet season it was in the sun almost the whole time, so was much warmer during the wet season. --Tango (talk) 18:51, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Just as in other places, the position of the sun in the sky at the same time of day has range of about 47° (twice the tilt of the Earth's axis) depending on the time of year. Rckrone (talk) 20:14, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- 47 degrees doesn't really mean anything to me viscerally- i very much notice that the day is shortening dramatically at my latitude- the day goes from bright from four till eleven to eight till four- i just wanted to compare Stanstaple (talk) 21:58, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The length of the day doesn't change considerably in the tropics because the Sun goes from 23.5 degrees one side of directly overhead to 23.5 degrees the other side. --Tango (talk) 22:45, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- 47 degrees doesn't really mean anything to me viscerally- i very much notice that the day is shortening dramatically at my latitude- the day goes from bright from four till eleven to eight till four- i just wanted to compare Stanstaple (talk) 21:58, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

ptsd

if you had ptsd how long does it last —Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.98.148.83 (talk) 19:43, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- You mean Posttraumatic stress disorder? According to Posttraumatic stress disorder#Diagnosis, it has to last more than a month to count as PTSD. I think it can last the rest of someone's life in some cases. --Tango (talk) 19:49, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- OR my father had PTSD arising from his treatment in a Japanese POW camp during WW2. It lasted until the day before he died 60 years later. Of course it was never treated, as PTSD was only recognised as a treatable condition comparatively recently. --TammyMoet (talk) 10:44, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Glitch in thermochemistry calculation

Okay, so I have this little problem:

- A 100-gram rod of copper (specific heat 0.385 J/g) at 100ºC is immersed in 50 grams of water (specific heat 4.18 J/g) at 26.5ºC. What will the temperature be when both components achieve thermal equilibrium?

And I have tried to solve it as follows:

- From the information given, we can calculate that when copper cools by 1ºC, it releases 38.5 joules. On the other side, water needs 209 joules to gain 1ºC.

- Therefore, we can produce the following equations:

- and

- where x represents the amount of joules gained/lost by the component, and y represents the temperature of the component.

- To know where the equations intersect, we make them equivalent:

- We simplify:

- Now that we know that each component has gained/lost 2,371 joules, we can use that in the original equation to find out the gain/loss of temperature. Let's do it for copper:

- Therefore, that means that copper has lost 61.59ºC, i.e. its temperature at equilibrium is 38.41ºC. Nevertheless, my textbook gives a value of 37.9ºC. Did I make a mistake, or is this small deviation due to differences in rounding up/down numbers? Thank you. Leptictidium (mt) 19:52, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think you made an error simplifying - I get x=2389.566667, albeit on the back of an envelope and as yet unchecked.

--Tagishsimon (talk) 20:17, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'm sorry for asking what is probably a very stupid question, but where does the 8046.5 come from? Leptictidium (mt) 20:48, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's 38.5*209 ... just some convenient figure allowing me to get rid of both fractions. --Tagishsimon (talk) 20:51, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'm sorry for asking what is probably a very stupid question, but where does the 8046.5 come from? Leptictidium (mt) 20:48, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Technically specific heat is temperature-dependent -- heat capacity falls as temperature decreases (it is zero at 0K). If you have 1 mol copper at 0C and 1 mol copper at 100C, their equilibrium temperature will actually be higher than 50C, because for each joule of heat transferred, the colder object increases in temperature faster than the hotter object falls in temperature per joule of heat. (This is what makes heat transfer from hot to cold thermodynamically irreversible.) John Riemann Soong (talk) 16:43, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, but that level of accuracy isn't usually taught to first-year chemistry students, with good reason. First, one must understand the concept of specific heat before one can deal with the issue of temperature dependence of specific heat. The OP does not indicate what chemistry class he is taking, but it is likely this is simply general chemistry. --Jayron32 21:19, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Note: There is also another way of working it out

- 1. 100g copper going from 100°C to 26.5°C would release 100*0.385*(100-26.5) = 2829.75 J

- 2. Sum the copper and Water heat demands (also known as a "Water Equivalent") 50*4.18 + 100*0.385 = 247.5 J/K (wt * Cp = g * J/g/K = J/K) (Cp units are J/g/K not J/g as you shown above)

- 3. Divide (1) by (2) for the temp rise for the combined copper/water system 2829.75/247.5 = 11.4333K

- 4. Add (3) to the start temp = 26.5 + 11.4333 = 37.9333°C

- Note: There is also another way of working it out

looking at yellow or bright purple stuff for a long time

From my personal observence, okay I wear yellow goggles at night when I sleep. When I wake up when I take off the yellow goggle I still see white stuff for white. If humans look at yellow or purple stuff for a long time I thought white stuff will stay white, and it will not look blue or lime green. Since when I took off the yellow goggle I didn't see white as blue. Will yellow and purple just look less vivid? --209.129.85.4 (talk) 20:22, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The human brain compensates for ambient light (wearing yellow goggles would be the same as having the room illuminated by a yellow light). You know what things ought to be white and your brain works out what the ambient light must be and then compensates for it so you see things the colours they would be under white light. If you were in unfamiliar surroundings and didn't know what colours things should be, then your brain might get it wrong or it may take some time to work it out. --Tango (talk) 20:34, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Why do you wear yellow goggles when you sleep? Looie496 (talk) 20:39, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- I do not think that the brain will know that you are wearing yellow goggles when you sleep because your eyes are going to be closed and it will presumably be dark. What colors do you think there are that need compensation under those conditions? Googlemeister (talk) 15:34, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

UFO identification

|

This question inspired an article to be created or enhanced: |

I snapped these beautiful critters on Sunday at the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. Can anyone please help identify them? Also, please advise if these pics are the best of their type and pick the best ones between the duplicates. I'm loathe to upload the full res versions if we already have better pictures in our articles. Also, anyone with a good eye for composition feel free to crop these photos (or even just draw borders on the existing) as you see fit. The full res pics are 8MP so I should be able to throw away plenty of pixels and still have something usable.

Photographic critique would be greatly appreciated. Also what's the best way to go about editing these? They are taken with a Canon EOS 350D in Adobe RGB color space, will The GIMP handle it properly? (The low-res versions have been created with Windows Image Resizer PowerToy, causing some colour "bleeding" which I put down to it not playing nice with Adobe RGB.) Or should I just upload the originals and request our WP:Graphic Lab to do the touching up? Regards. Zunaid 20:37, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Dropped by further to message on the WP:photo page. Don't have enough time to upload crops, but here's my 2¢... calling them #1 to #7, clockwise from top left: 1 is a good in-flight shot and more worthy of gallery space than others there, crop slightly (15%) from all sides except top; 2 is better than 3 by far, crop as before, possibly a little tighter than before, try 25%; 5 is ok but probably doesn't illustrate so much more than the others on the page that I'd want to find space for it; 6 needs heavily cropping from all sides before I can even evaluate it; 7 has more detail in the body than 4 and tells me more about the wings, could do with a 20% crop from the right and is really very nice, be a shame not to use it somewhere. I'd put these up at about 1500x1000px to be of real value, and if you're getting weird results with colour profiles maybe the Lab would be a good idea, I'm not sure the GIMP handles profile conversion any better than WIRPT. Hope that's been some help. mikaultalk 05:33, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

-

Valley carpenter bee, Xylocopa varipuncta. Slightly clipped on top but in focus.

-

Valley carpenter bee, Xylocopa varipuncta. Not clipped off but slightly out-of-focus. which one to choose?

-

Acraea sp., Heliconiinae. Which pic is best?

-

Oxythyrea sp. Identify the flower. Crop needed? Is this photo needed? The article has much better close-ups.

- I don't know the answer, but I put them in a gallery for you so I thought I'd leave a message to let you know. They're beautiful, but I don't see much photography. Vimescarrot (talk) 21:08, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks. I've edited some captions. Check out the pics in our bee article for some REALLY superb photography. This is rather second-rate in comparison. Zunaid 21:26, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The first one is a carpenter bee, Xylocopa sp.. The last one is Oxythyrea sp. (I'm going to write a stub article for that one soon). The butterfly species name eludes me for a moment, but it will come back to me in a minute or two. --Dr Dima (talk) 23:14, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Done: Oxythyrea article stub is up. --Dr Dima (talk) 06:56, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The before-last one (middle one in the lower row) is also a chafer beetle, family Scarabaeidae; there is not enough resolution to make a more accurate identification. --Dr Dima (talk) 23:47, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The butterfly in pictures 4 and 5 is Acraea sp. (Heliconiinae). --Dr Dima (talk) 03:18, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Thanks for the ID's so far Dr. Dima. Photographic critique and input needed. A lot of the linked articles already have sufficient (and better IMHO) photos. Are these pics really then needed? Is there any other noticeboard I can spam for photographic input? Zunaid 10:51, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The second and third picture, the yellow carpenter bee, is most likely a male Xylocopa varipuncta, commonly called the Valley carpenter bee. Bugboy52.4 | =-= 01:08, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

Thanks. Do our articles really need these pictures? Especially when compared to those already in the articles? Should I upload high res versions? Zunaid 04:55, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- If in doubt, you can at least publish them to EOL. They have a group on Flickr where you can upload images and tag them appropriately to have the system add your photo to the encyclopedia. I've submitted several myself, some of which are the only photos there of the species. Bob the Wikipedian (talk • contribs) 17:44, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

vision acuity over 20/400

Is this possible to have vision over 20/400. Do anybody have like 20/1000 or 20/700. From corneal scar I have had my vision was 20/400--209.129.85.4 (talk) 20:56, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- This article [1] implies that such Snellen fractions do exist. --Cookatoo.ergo.ZooM (talk) 21:14, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, only being able to detect light and dark as if your eyes were closed could be described as 20/infinity. --Tango (talk) 22:15, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you consider what those two numbers mean, it's clear: 20/100 (for example) would mean a person who is only able to read letters that a normally-sighted person can read at 100 feet if they move to 20 feet away from them. For there to be 20/1000 vision, you'd have to be only just able to see letters at 20 feet that someone with normal vision could see at around two tenths of a mile! Normal vision allows you to recognise letters when they subtend only 1/12th of a degree. So for someone to have 20/1000 vision would mean that they'd only just be able to read letters about 18 inches tall from 20 feet away. SteveBaker (talk) 03:44, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It doesn't have to be letters. It's just about resolving an image, whatever that image may be. The page linked to says the common way to measure 20/1000 vision would by getting to person to count fingers, in this case at 8 feet distance (although you would just report "CF 8'" rather than converting it to 20/1000). I guess that means that someone with normal vision can distinguish fingers at 400 feet (which sounds about right to me). --Tango (talk) 03:56, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Isn't vision worse then 20/400 classified as legally blind anyways? Googlemeister (talk) 15:31, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Depends on jurisdiction, but about that. There is more to life than whether or not you can claim benefits, though. --Tango (talk) 17:32, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Isn't vision worse then 20/400 classified as legally blind anyways? Googlemeister (talk) 15:31, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It doesn't have to be letters. It's just about resolving an image, whatever that image may be. The page linked to says the common way to measure 20/1000 vision would by getting to person to count fingers, in this case at 8 feet distance (although you would just report "CF 8'" rather than converting it to 20/1000). I guess that means that someone with normal vision can distinguish fingers at 400 feet (which sounds about right to me). --Tango (talk) 03:56, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Human - 23 chromosome pairs

What happens when one is born with more or less than 23 pairs? --Reticuli88 (talk) 21:39, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- It will cause one or another disease. There are many, depending on which chromosome was duplicated/deleted. See Aneuploidy. Someguy1221 (talk) 21:43, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- The result will be a genetic disorder, not a disease. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 02:40, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, technically it will "kill" the potential life (well before birth approaches), and the (semi-)survivable diseases caused by the monosomy and trisomy Someguy refers to are the rare exceptions. ~ Amory (u • t • c) 22:34, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. Miscarriage is often caused by a fault in the genes. --Tango (talk) 22:42, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- According to the disease link - "A disease is any medical condition that impairs bodily function." Some genetic disorders will impair bodily function and will therefore be be diseases. In reality I'm struggling to think of a genetic disorder that would not impair bodily function. Richard Avery (talk) 08:38, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It wouldn't be a disorder if it didn't impair bodily function, it would be a neutral or beneficial mutation. Was anyone questioning the definition of disease? --Tango (talk) 17:42, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- According to the disease link - "A disease is any medical condition that impairs bodily function." Some genetic disorders will impair bodily function and will therefore be be diseases. In reality I'm struggling to think of a genetic disorder that would not impair bodily function. Richard Avery (talk) 08:38, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. Miscarriage is often caused by a fault in the genes. --Tango (talk) 22:42, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

Biological distinction between Sickness and Contagiousness in Contagious diseases.

I understand that people can be contagious but not ill during the incubation stage of a disease. The opposite, being ill but not contagious, is commonly said to exist at the tail end of a disease. What is going on biologically during both of these periods? I'm starting to think that latter is a bit of folk science invented by ill people who are feeling cooped up and better enough to want to rejoin the world. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 23:12, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Certainly not. Infections are only contagious if they can be spread from person to person either directly or indirectly. If infectious particles exist in bodily fluids like sputum, semen and feces, spread can occur when shaking hands with an infected individual allows for a closed fecal-oral route of transit. That's great for transfer of things like E. coli and Hepatitis A. But certain infectious organisms do not congregate in fluids -- they may prefer to hide in other places (if not entirely, then at least for some portion of their infectious existence) or take on a noninfectious form when they are in certain fluid. Syphilis, for example, has three clinical phases -- patients with secondary syphilis are the most infectious, even though the infectious spirochetes are present from the time of inoculation. DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 02:53, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- But why or how would an organism become noninfective. It would essentially be committing suicide if it did so willingly. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 03:57, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- A pathogen is incapable of "becoming noninfective... willingly", as neither bacteria nor viruses have a free will. Rather, the outcome is decided by a competition between the pathogen and the immune system of the host. A viral or bacterial infection only rarely results in the death of the host. (That depends on the species of the pathogen and on the immune response of the host, of course). In most cases, pathogen is completely neutralized by the immune system of the host; at this stage the host no longer emits the pathogen. In some cases pathogen survives, and the infection becomes chronic and/or asymptomatic. In those cases the host remains a carrier of the pathogen, and may transmit it to others. --Dr Dima (talk) 05:41, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Of course free will is an illusion, but people use it all the time. What I meant was that if information in it's own genome shut it down, why? And if information in the human genome shut it down, how? And if the disease is inactivated then why are you still considered sick? This is what I have now: the human immune system becomes able to neutralize the germs and quickly does so. The person still shows symptoms because it takes a while to repair the damage. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 16:47, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- A pathogen is incapable of "becoming noninfective... willingly", as neither bacteria nor viruses have a free will. Rather, the outcome is decided by a competition between the pathogen and the immune system of the host. A viral or bacterial infection only rarely results in the death of the host. (That depends on the species of the pathogen and on the immune response of the host, of course). In most cases, pathogen is completely neutralized by the immune system of the host; at this stage the host no longer emits the pathogen. In some cases pathogen survives, and the infection becomes chronic and/or asymptomatic. In those cases the host remains a carrier of the pathogen, and may transmit it to others. --Dr Dima (talk) 05:41, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- But why or how would an organism become noninfective. It would essentially be committing suicide if it did so willingly. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 03:57, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It may be helpful to remember that the feeling you get of "being sick" is not entirely caused directly by the pathogen, but also includes your body's response to that pathogen (or, in the case of allergies, the body's response to something mundane). For example, fever often accompanies an infection such as the influenza, but many respiratory viruses prefer (or require) slightly cooler areas to do their dirty work. What's going on? Your body is raising its core temperature to help the fight against the infection. At other times, your body will react in a way that also suits the virus. For example, a runny nose helps flush the virus from your sinuses, but also aids the virus in spreading by releasing infectious material. But your incredibly complicated immune system sometimes runs rampant and sometimes simply keeps running after it no longer needs to. So, while your nose may be running as part of your body's attempt to flush your sinuses, the virus may now be long gone. This is apparently quite common when it comes to cough (OR alert) - coughing irritates your windpipe, which leads to... coughing... which irritates your windpipe. Your infection may be dead and gone for weeks and yet you keep on coughing because your throat is so badly worn out. I've had that situation (as diagnosed by a doctor): stop the cough by any means necessary for even a day or so and the rest of the problem just collapses. So, I was hacking like a hound-dog for a month but was completely non-infectious. Matt Deres (talk) 17:55, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

If "Big bang" is accurate...

If the universe's big bang beginning is accurate, then at that time all matter was together. We are also told that the light from distant galaxies hasn't made it all the way across the universe yet. I imagine that there is lots of relativity and stuff involved, but surely for both statements to be true some matter needs to have moved at faster than the speed of light. What am I misunderstanding? -- SGBailey (talk) 23:36, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, we can see almost all the way to the big bang itself. Just a short while after the big bang, the universe became clear and light could start traveling. We can see back to this wall and it is called the cosmic microwave background radiation. But events which happened too recently for light from them to reach you, you cannot see yet. Even when you pour yourself a cup of coffee you can't observe it for a time = armlength/C. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 23:46, 3 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's generally assumed that everything in the universe came from one place, because it's hard to see how it could be so homogeneous otherwise. So it's all in our past light cone. But we can't see everything. The picture is something like this:

* /\ ^

@ / \ |

/ \ |

################## time

- We're at the top center and #### is the primordial fireball (the source of the cosmic microwave background). We can't see the event marked *, but we can see the matter that later does *. We can't see the event marked @ and we also can't see the matter that later does @, because the universe is opaque below the ####. But in principle if you extend the diagonal lines through the fireball they encompass the whole universe. The "edge of the visible universe" is defined by where the light cone hits the fireball. -- BenRG (talk) 00:51, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- We need to be careful with our terminology. You are using "universe" to mean "observable universe" (which means everything that can be theoretically observed, not just things that can be observed using EM radiation). Anything outside the observable universe can't have any impact on us, so in a sense we can just say it doesn't exist (which is why people do often abbreviate the observable universe to just "universe"), but in another sense it is very likely that it does (the size of the universe happening to exactly correspond with the size of the observable universe would be a massive coincidence unless there is something going on that we don't know about - alternatively, the universe could be smaller than the observable universe, in which case we should be able to see the same objects multiple times as the light goes all the way around the universe). --Tango (talk) 01:00, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- We're at the top center and #### is the primordial fireball (the source of the cosmic microwave background). We can't see the event marked *, but we can see the matter that later does *. We can't see the event marked @ and we also can't see the matter that later does @, because the universe is opaque below the ####. But in principle if you extend the diagonal lines through the fireball they encompass the whole universe. The "edge of the visible universe" is defined by where the light cone hits the fireball. -- BenRG (talk) 00:51, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The expansion of the universe isn't matter moving outwards through space, it is the space itself expanding. There is no speed of light limit on the expansion of space, just on matter moving through space. See Metric expansion of space. The standard analogy is blowing up a balloon with dots on it. The dots are stationary compared to the bit of balloon they are on, but they move apart from each other as the balloon expands. The further apart they are, the faster they move apart. For objects far enough away from us, they are moving away from us (or, rather, the distance between them and us in increasing - they aren't actually moving, that's the point) faster than the speed of light. At the moment, the relevant distance is about 45 billion light years, I believe. --Tango (talk) 00:07, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Many processes in physics are reversible. If no rules of physics are violated when "space" expands, then could it similarly contract without violating any law of physics? Hypothetically speaking, could the space between planet A and planet B (initially 10 light years) contract to .1 light year, making a trip between them much more convenient, so that it could be completed at .01 c in 10 years? By definition, there would be no faster than light travel. If we cannot explain why space expanded, can we set limits on the geometry of any future expansion (or useful contraction)? Edison (talk) 04:26, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, metric expansion can run in reverse. It's not expected to ever happen in our universe, but a Big Crunch was once hypothesised as a possible end of the universe. I don't think it would make interstellar travel easier, though - if the universe contracted far enough to make a different within a single galaxy then I think it would pretty quickly end up destroying any habitable systems. --Tango (talk) 17:50, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Many processes in physics are reversible. If no rules of physics are violated when "space" expands, then could it similarly contract without violating any law of physics? Hypothetically speaking, could the space between planet A and planet B (initially 10 light years) contract to .1 light year, making a trip between them much more convenient, so that it could be completed at .01 c in 10 years? By definition, there would be no faster than light travel. If we cannot explain why space expanded, can we set limits on the geometry of any future expansion (or useful contraction)? Edison (talk) 04:26, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Question - Metric expansion of space says there are two reasons for expansion: inertia and a repulsive force. Inertia is a property of matter and forces act on matter so it sounds like expansion is matter just moving apart. I understand (from reading this desk) that the velocity at which an object moves away from us can be more than c because time (in that measure of velocity) is based on a clock moving with the object which slows down as it moves. My question is: how do the two reasons above "fit" with space itself expanding? Zain Ebrahim (talk) 08:15, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'm not entirely sure about this bit (BenRG has tried to explain it to me, but I've never been entirely convinced). Even excluding the cosmological constant (which models that repulsive force you mention), the expansion isn't just inertia as we would usually consider it. It is caused by inertia, but that inertia causes the space itself to expand, that allows greater than light speed expansion. --Tango (talk) 17:50, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Question - Metric expansion of space says there are two reasons for expansion: inertia and a repulsive force. Inertia is a property of matter and forces act on matter so it sounds like expansion is matter just moving apart. I understand (from reading this desk) that the velocity at which an object moves away from us can be more than c because time (in that measure of velocity) is based on a clock moving with the object which slows down as it moves. My question is: how do the two reasons above "fit" with space itself expanding? Zain Ebrahim (talk) 08:15, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Note that in the balloon example, inertia of the balloon surface itself (or tiny little pieces of lead fixed to the surface, if that's an easier analogy) would pull the balloon further apart, and even in a way that the distance between any two pieces on the surface would grow faster than the distance between the same two pieces in 3-D space. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 18:08, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Can the "balloon" have "outward" "inertia"? The "outward" direction isn't really a direction at all from the perspective of someone on the balloon. I don't have a good understanding of this topic, but this seems very strange to me. Rckrone (talk) 23:44, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The balloon, yes, certainly. Matter in the real universe - I don't know, but I suspect so. Otherwise, the interia vs. gravity argument makes no sense. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 13:11, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Can the "balloon" have "outward" "inertia"? The "outward" direction isn't really a direction at all from the perspective of someone on the balloon. I don't have a good understanding of this topic, but this seems very strange to me. Rckrone (talk) 23:44, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Note that in the balloon example, inertia of the balloon surface itself (or tiny little pieces of lead fixed to the surface, if that's an easier analogy) would pull the balloon further apart, and even in a way that the distance between any two pieces on the surface would grow faster than the distance between the same two pieces in 3-D space. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 18:08, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Scratches head... Um, a quick break for a WP:OR or WP:SYNTH might be helpful! I don't particularly think Wikipedia is for writing essays on theoreticals like this. Don't make me insist you all find citations! This isn't a defined talk page so I think that means I can request them :) ♪ daTheisen(talk) 16:01, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Our priority here is answering the OP's question in a way they can understand. If linking them to a reference they can read for themselves is the best way to do that, we'll do it. If writing out a detailed answer ourselves is better, we do that. Finding citations isn't really necessary unless there is a dispute. --Tango (talk) 17:50, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Thanks all. I don't think I understand it as well as I want yet, but I understand it more than I did. -- SGBailey (talk) 11:44, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

November 4

Spiritual Science. Rectifying Hypotheses

can i create my own hyperlink-web here of my findings and studies with this 'spirituality'? i believe people would be interested in these things. i simply would like to be recognized as the author. please tell me my options. i simply want this question answered, i will not waste my time. —Preceding unsigned comment added by Love me alway (talk • contribs) 03:55, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sorry, but Wikipedia is not a venue for original research. — Lomn 04:05, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Such a compilation may be acceptable on your user page or in a user-space sub-page. See the Help for User Subpages and guidelines for allowable subpages. Again, Wikipedia is not the place to conduct original research; but if you are merely compiling and organizing links to other Wikipedia articles that you find useful, you can put it in your user space. This area has a little less regulation for content, as it is not technically part of the encyclopedia. As far as ownership, all content must be submitted under the Creative Commons and GFDL licenses - keep this in mind. You do not own your user-page or the content you submit to it. Finally, remember that even though Wikipedia offers you some freedom in the user-page space, Wikipedia is not your web host. Our goal is to write an encyclopedia; your user-page space is really supposed to help you (and others) to make contributions to actual encyclopedia articles. Nimur (talk) 05:58, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Submitting material to Wikipedia is unwise if you wish to be recognized as the author. You could easily be accused later of copying (your own text) from Wikipedia. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:16, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- You can generally prove that you were the author of a particular thing by examining the "history" of the item in question. However, there is nothing whatever you can do to prevent someone from changing what you wrote - or copying it - or deleting it - or anything else. The open licensing of Wikipedia not only allows that - it actively encourages it. However, your own "findings" about something are completely unwelcome here. The goal is for all information to be generated in a neutral manner by reference to respected source material. Nothing you think up for yourself is allowed into any Wikipedia article...so what you suggest would likely be vehemently opposed from all sides! SteveBaker (talk) 22:13, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I interpreted "findings" to mean "things the OP found on the web and wants to link to." If the "findings" are actually synthesis of original research, then as Steve has pointed out, they should not be published on Wikipedia. We have a strong policy against publishing original research here. Nimur (talk) 17:44, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

Name reactions in Chinese Wikipedia

Look at the articles about name reactions in Chinese Wikipedia. Why don't they translate the names into Chinese? --128.232.251.242 (talk) 10:37, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Chinese is in general iconic rather than sound based. The problem is with us using Chinese designations as they'd see it is us not using the proper icon but just a particular sound. Dmcq (talk) 10:54, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- But almost all the people do have a Chinese name, with almost no exceptions, for instance see zh:Category:Living people. Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe translates to zh:阿道夫·威廉·赫尔曼·科尔贝 in Chinese. So why don't they translate the name Kolbe in Kolbe electrolysis into Chinese? --128.232.251.242 (talk) 11:12, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I didn't see any specific guideline there about it. I guess their chemists must just find it easier. You could always ask on a talk page there. Dmcq (talk) 12:33, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- They don't translate the name because it's a proper noun specifically referring to the reaction. If it were also translated it would be a generic adjective of something. It looks odd because of the huge contrast between roman characters, but it's standard convention in most types of math and science to hold the names. Just because it was able to translate "Kolbe" doesn't mean it came out as "Kolbe"; in its eyes it translated "kolbe", which is a very important distinction. This all happens a whole lot in Japanese, too. Why don't we use their characters for their historical persons or theorems? It's "mostly" easier to move into a lettered format than from that into complex characters. I don't know the term of it in traditional Chinese, but it's "Romanji" in Japanese, literally the romanization of the real language so that most anyone in the world can try to pronounce a word. A nod to European influence via early trading routes into the long-established Eastern cultures. ♪ daTheisen(talk) 15:53, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the reason is really because people are lazy and there are many different (conflicting) complex standards for transliterating foreign names. PRC, Hong Kong and Taiwan all have different transliteration schemes with different characters, which editors would need to deal with using templates, which has quite a learning curve. It's nowhere near as simple as romaji for Japanese, and it's further compounded by the great firewall of China (although I heard Wikipedia's been unblocked?). --antilivedT | C | G 06:17, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- They don't translate the name because it's a proper noun specifically referring to the reaction. If it were also translated it would be a generic adjective of something. It looks odd because of the huge contrast between roman characters, but it's standard convention in most types of math and science to hold the names. Just because it was able to translate "Kolbe" doesn't mean it came out as "Kolbe"; in its eyes it translated "kolbe", which is a very important distinction. This all happens a whole lot in Japanese, too. Why don't we use their characters for their historical persons or theorems? It's "mostly" easier to move into a lettered format than from that into complex characters. I don't know the term of it in traditional Chinese, but it's "Romanji" in Japanese, literally the romanization of the real language so that most anyone in the world can try to pronounce a word. A nod to European influence via early trading routes into the long-established Eastern cultures. ♪ daTheisen(talk) 15:53, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I didn't see any specific guideline there about it. I guess their chemists must just find it easier. You could always ask on a talk page there. Dmcq (talk) 12:33, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- But almost all the people do have a Chinese name, with almost no exceptions, for instance see zh:Category:Living people. Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe translates to zh:阿道夫·威廉·赫尔曼·科尔贝 in Chinese. So why don't they translate the name Kolbe in Kolbe electrolysis into Chinese? --128.232.251.242 (talk) 11:12, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- In fact our own languages reference desk would probably be best at WP:RD/L. My guess is that people read and write about chemistry but names of people and places are things one says. Even so you will quite often see some special name translated by meaning rather than sound into English. Dmcq (talk) 15:42, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

It's a myth that Chinese is iconic rather than sound-based. All languages are phonetic, but not all languages have a phonemic writing system. John Riemann Soong (talk) 16:39, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- All spoken languages are phonetic. Sign languages are not, and it is possible to have an entirely written language which is not simply a representation of a spoken language. In fact, I gather written literary Chinese (Literary Sinitic) is quite close to this [2]. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 18:38, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Which is what I meant. It can be pronounced very differently in different dialects. Dmcq (talk) 22:27, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Not only pronounced differently: it is a different language to most (all?) of the 'dialects'. Children who have a mother tongue other than Mandarin (and even those who have Mandarin?) have to learn it in order to write. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 22:37, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Classical Chinese may be helpful here Nil Einne (talk) 10:01, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Excellent. And it links to Vernacular Chinese, which is the one that children have to learn Mandarin to be able to read. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 16:28, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Classical Chinese may be helpful here Nil Einne (talk) 10:01, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Not only pronounced differently: it is a different language to most (all?) of the 'dialects'. Children who have a mother tongue other than Mandarin (and even those who have Mandarin?) have to learn it in order to write. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 22:37, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Which is what I meant. It can be pronounced very differently in different dialects. Dmcq (talk) 22:27, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

universities

can i known what are the top universities in uk for m pharmacy —Preceding unsigned comment added by Nagtej (talk • contribs) 13:39, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sorry, I'm not sure how I can help. The same way that Wikipedia isn't a source or original research, we also can't try to create new ideas using information from Wikipedia. We hold to a standard of neutral point of view in articles, so there would be no way to to make guesses like that even if we thought we should! Good luck... ♪ daTheisen(talk) 15:57, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The QUB School of Pharmacy has been rated as the top Pharmacy School in the UK in the 'Times Good University Guide 2010' [www.qub.ac.uk/schools/SchoolofPharmacy/dl/] and The University of Nottingham in the 2006 Times Good University Guide [www.nottingham.ac.uk/pharmacy/undergraduates/index.php]. Tracking down the mentioned guide will surely lead to others. 75.41.110.200 (talk) 16:13, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- UCAS (Universities & Colleges Admissions Service) can help you with information on undergraduate degree programmes at UK universities and colleges.Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:10, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yet another best of list at the guardian. --Tagishsimon (talk) 16:14, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- UCAS (Universities & Colleges Admissions Service) can help you with information on undergraduate degree programmes at UK universities and colleges.Cuddlyable3 (talk) 16:10, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The QUB School of Pharmacy has been rated as the top Pharmacy School in the UK in the 'Times Good University Guide 2010' [www.qub.ac.uk/schools/SchoolofPharmacy/dl/] and The University of Nottingham in the 2006 Times Good University Guide [www.nottingham.ac.uk/pharmacy/undergraduates/index.php]. Tracking down the mentioned guide will surely lead to others. 75.41.110.200 (talk) 16:13, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sorry, I'm not sure how I can help. The same way that Wikipedia isn't a source or original research, we also can't try to create new ideas using information from Wikipedia. We hold to a standard of neutral point of view in articles, so there would be no way to to make guesses like that even if we thought we should! Good luck... ♪ daTheisen(talk) 15:57, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- See here for the Times Good University Guide for Pharmacology and Pharmacy. --Tango (talk) 17:53, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

Was the discovery of evolution "inevitable" in the 19th Century? Why

I visited an aquarium last week, and one of the exhibits said that because of changes in scientific thinking the discovery of evolution was "inevitable" in the 19th Century. It mentioned that Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace discovered it independently, and said that even if they had not seen it the theory's time had come and someone else would have done soon. Is this true, or if it was not for these two discoverers could we still not understand evolution today? If it is true what changes in thinking and previous discoveries made the theory of evolution inevitable? As a side question do you "discover", "invent", or "author" a theory - I don't know quite what to write! -- Q Chris (talk) 15:01, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's hard/impossible to speculate whether anything that already happened was "inevitable" but I'm fairly certain that someone else would have struck upon the idea before too long. A lot of the original theory was essentially "Wait a minute... That animal looks a lot like that other animal" and you don't need a rich guy or a traveler to notice that. The Great man theory is probably relevant here, but essentially it's not really possible to factually answer your question. ~ Amory (u • t • c) 15:14, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- Oh, and as for your last question, you can say "constructed" or "formulated." ~ Amory (u • t • c) 15:16, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- It was inevitable if you consider that genetic studies were independent of evolution. While the early studies didn't know anything about genes or DNA, they were tracing patterns of inheritance from parent to child, such as colors of kernels of corn and eye color in mice. Eventually, someone would have to recognize that traits were being passed from parent to child. As soon as someone were to stumble upon mutation, evolution would be evident. -- kainaw™ 15:20, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- The idea of evolution generally was well-known and well-discussed well before Darwin and Wallace. The idea of natural selection being the mechanism of evolution probably would have come out at some point if both of those two had been hit by a train before their time. This distinction is rather important. It is not a matter of saying "this animal looks like this one"—people had already been doing that for a long time, even in the scientific sphere (see, e.g. Erasmus Darwin, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and less scientifically, Robert Chambers, etc.).

- There were a lot of people thinking along similar lines at the time—it was definitely "in the air". Darwin is especially well-known because he articulated it in a rather careful form, with lots of evidence, and with all the power of his already-established scientific name attached to it. (Wallace was, in this sense, very much at a disadvantage.) He had powerful friends who assured that the theory would be taken seriously and given attention within the scientific community and not dismissed as just a variation on Lamarck or as just political claptrap (Cf. Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation).

- As for the distinction between "discoveries", "inventions", "authors"—it's a great question, one that professional historians have actually argued quite a lot about. It depends on your conception of authorship itself, and on your conception of what is to be authored. Are theories hanging out there "in the world", waiting to be discovered? Or is the process of articulating a theory a creative act as well as an objective one? I tend to think the answer is somewhere in between—there is a "core" reality to be "discovered", but the aspects of it that get written about, and the ways in which they are formulated in human language, and made convincing and compelling, are a definitely parts of an authorial intervention—an "invention", one could say. This is much easier to see as time goes on—Darwin's theory of natural selection, as he articulated it, contains quite a bit of "nature" in it, but it is very much a work of the particular man himself, and his formulation of it, his preoccupations, his way of arguing it, all reflect that very strongly. --Mr.98 (talk) 15:28, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- (ec, and now mostly redundant. But I wrote it, so you better read it ;-): "Evolution" was evident quite a while before Darwin and Wallace from looking at fossils. See history of evolutionary thought. Erasmus Darwin described evolution in the late 19th century, and Lamarck formulated his idea of species evolving to better meet environmental conditions in 1809. What Darwin (and Wallace) added was the mechanism of natural selection working on variations of inherited traits, not the idea of evolution itself. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 15:32, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I would argue that yes, evolution was an inevitable 'discovery'. It's extremely elementary that weak things are removed over time and robust things remain. It applies to everything across the spectrum, from the erosion of mountains, to biological features, to ruling powers. I suppose it appeared when it did as rationality was starting to question the religious hegemony of past centuries, not because the idea itself was necessarily of profound importance. Vranak (talk) 16:09, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think you underestimate the difficulty of making the scientific case (ignore the religious stuff for a moment—it mattered for some, not for others). Remember that when Darwin proposed evolution there was no good model for biological heredity at all, a relatively new knowledge of the fossil record, and no consensus over the age of the Earth. This makes making a compelling scientific argument about natural selection rather difficult. If the rate of change is too slow, and the Earth is too young, then it doesn't work. Without a model of heredity that allows for things like mutations, you don't have any way for speciation to take place. These are non-trivial concerns. There were plenty of people before Darwin who waived their hands and said "oh this is a common principle to all things so it applies to humans" (again, see Robert Chambers), but 1. they were more often than not wrong (because there are a lot of candidate "common principles"), and 2. they were totally uncompelling (because just because something works in one arena doesn't mean it works in another). Even in Darwin's case, it was not totally compelling—most scientists did not accept natural selection as the mechanism of evolution until long after he had died and the modern evolutionary synthesis was developed (some 70 years after Origin of Species!). (And this latter point has nothing to do with religion—they accepted evolution in general.) --Mr.98 (talk) 16:32, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you read The Origin of Species it's quite clear that Darwin wasn't proposing an original idea. Rather he did a lot of careful synthesis and research in order to champion an idea. The Origin gave a confused set of ideas clarity and made it obvious how and why they had to be true. I think you can divide scientific "discoveries" into three kinds;

- "wtf is this" discoveries, finding something, such as a fossil or a strange unexpected residue, eg Ardi or teflon

- "eureka" discoveries, a sudden stroke of genius like the Dirac equation and Archimedes' principle

- "synthesis" "discoveries" like the theory of evolution or plate tectonics. These are the best and hardest.

- In the popular imagination, people think science is largely of the "eureka" type, which are actually probably the rarest. -Craig Pemberton (talk) 16:45, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

- I like that classification, and I will make the phrase "wtf discoveries" part of my working vocabulary ;-) --Stephan Schulz (talk) 18:10, 4 November 2009 (UTC)

self-ionisation of glacial acetic acid

How does it compare to water? How does the entropy contribution of the reaction change? What about enthalpy of self-ionisation? John Riemann Soong (talk) 16:37, 4 November 2009 (UTC)