Wikipedia:Reference desk/Language: Difference between revisions

| Line 404: | Line 404: | ||

:::English is a hodge-podge, so it depends on what point in time you consider modern English to have begun. ←[[User:Baseball Bugs|Baseball Bugs]] <sup>''[[User talk:Baseball Bugs|What's up, Doc?]]''</sup> [[Special:Contributions/Baseball_Bugs|carrots]]→ 02:18, 11 November 2009 (UTC) |

:::English is a hodge-podge, so it depends on what point in time you consider modern English to have begun. ←[[User:Baseball Bugs|Baseball Bugs]] <sup>''[[User talk:Baseball Bugs|What's up, Doc?]]''</sup> [[Special:Contributions/Baseball_Bugs|carrots]]→ 02:18, 11 November 2009 (UTC) |

||

= November 11 = |

|||

== Prison learning == |

== Prison learning == |

||

Revision as of 12:56, 11 November 2009

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

November 5

Threat?

I have a question. What could be considered a threat? Here are some possibilities:

- If you touch that cord, I will make you regret it.

- Ricardo, if I ever hear you talking about Keynes's opinions again, I'm going to close this classical thread.

- Don't come close to me, or else I'm going to scream.

I think all 3 of these things are threats. Some are worse than others (I'd rank 1st, 3rd, and 2nd, in terms of "threath seriousness"). What do the rest of you think? Can anyone provide me a good definition for "threat"?

Thanks in advance.--MarshalN20 | Talk 03:04, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- There is obviously a fine line between a "threat" and a "promise". ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 03:41, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Often dictionaries are good with definitions: "A declaration of an intention or determination to inflict punishment, injury, etc., in retaliation for, or conditionally upon, some action or course." Threats can be conditional statements (if X, then Y) or they can omit the conditional with the assumption that the conditions have already been met.

- By the way, Bugs, I find the distinction between threat and promise to be disengenuous. Threats and promises are not mutually exclusive from each other. — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 06:49, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- That would be the point. In essence, they are the same thing: a pledge to take action of some kind. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 07:59, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- ... except that a threat is always a pledge to do something bad, whereas a promise may be (and often is) a pledge to do something good. Mitch Ames (talk) 09:25, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- ... except when someone says, "That's not a threat, it's a promise!" Which is what I was originally alluding to. :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 17:23, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- ... except that a threat is always a pledge to do something bad, whereas a promise may be (and often is) a pledge to do something good. Mitch Ames (talk) 09:25, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- That would be the point. In essence, they are the same thing: a pledge to take action of some kind. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 07:59, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- If a sadist said to a masochist that he/she (the sadist) was going to deny him/her (the masochist) sexual favours, that could be said to be a threat from the sadist's perspective, and a promise from the masochist's perspective. -- JackofOz (talk) 09:33, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks for the help. So, based on what has been argued here, the 3 statements I posted could be considered threats (or promises, which depends on perspective). Yes, dictionaries are good with definitions, but the discussion here was better.--MarshalN20 | Talk 13:20, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sometimes there is a fine line between a "threat" and a "warning". "Warning" meaning a statement that is made in order to protect someone. -- Irene1949 (talk) 22:55, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, that just makes it a tad more confusing. Wouldn't a "warning" be something along the lines of the common Wiki warning: "Please don't vandalize articles in Wikipedia, further disruptive behavior may result in a block." The effective uses of "please" and "may" are effective ways of warning without being threatening, but the three options I originally posted at the start of this discussion are not warnings (they're threats). Or, does anybody have another opinion?--MarshalN20 | Talk 23:05, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- I imagine that one may "warn" (as opposed to threaten) of both potential (rather than absolute) negative consequences as well as those that are not caused by the speaker (e.g. Don't play in the street or you'll get run over). — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 00:07, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well, that just makes it a tad more confusing. Wouldn't a "warning" be something along the lines of the common Wiki warning: "Please don't vandalize articles in Wikipedia, further disruptive behavior may result in a block." The effective uses of "please" and "may" are effective ways of warning without being threatening, but the three options I originally posted at the start of this discussion are not warnings (they're threats). Or, does anybody have another opinion?--MarshalN20 | Talk 23:05, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think that it is the intention which makes the difference between a warning and a threat. A statement like "If you do A, then B may happen to you" is a warning when it is made in order to protect someone from B–and it is a threat when it is made in order to prevent someone from doing A. It is possible that a statement is a warning and a threat: somebody might dislike A just as B. For exemple, a wikipedian might dislike disruptive behavior just as he dislikes blocks. -- Irene1949 (talk) 19:04, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

Old Norse

I'm curious about the meaning of the *, R and RR symbols I found in a lot of Old Norse given names and common words. For example: *SvartgæiRR, HrókR, ÁvæiRR. Do they have a specific influence on pronunciation? --151.51.14.218 (talk) 11:09, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- The * will be asterisk#Historical linguistics. Algebraist 11:16, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- The R is the transliteration of the Younger Futhark rune "yr" (an upside-down algiz), which represented a sound that is reconstructed as z in Proto-Germanic but is spelled r in Old Norse texts written with the Latin alphabet rather than runes. It's uncertain what its exact pronunciation was; all we know is that it's a sound that used to be /z/ and later turned into /r/. +Angr 14:36, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

Spanish Main

Does the Spanish have an equivalent for the English Spanish Main? (By the way, I don't find a Spanish Wikipedia. Is there one?)--Omidinist (talk) 12:36, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- In answer to your second question, the Spanish Wikipedia can be found here. You can get to it from Wikipedia's main page and clicking on the bit where it says 'Español' on the right. --KageTora - SPQW - (影虎) (talk) 12:41, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

Anthony Trollope's book The West Indies and the Spanish Main seems to be translated in Spanish as Las Indias occidentales y el continente español. Actually, continente means continent, mainland, but not coast, so I'm not very sure about it. --151.51.14.218 (talk) 13:15, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- The English is a romantic phrase without equivalent in Spanish, AFAIK. I've only ever heard it referred to it as las costas del Caribe, even with reference to pirates and the like. Continente in the context above obviously doesn't refer to the coastline at all, and perhaps shows the English phrase to be understood as a descriptor for the whole region. mikaultalk 19:34, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- So far, so good. Thank you all people. More comments are welcome. --Omidinist (talk) 19:43, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Tierra Firme.[1] —eric 20:23, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Tierra firme is a general nautical term. Maybe tierra firme de las Indias Occidentales can be an option. As it has been said, there is no direct equivalent in common use. Up to now, the most precise term in general use I have found is es:cuenca del Caribe, but I'm not convinced. :( 200.49.224.88 (talk) 22:21, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- The central response is that there is no direct translation to Spanish Main. Las costas del Caribe español (The coasts of the Spanish Caribbean) is the closest translation.--MarshalN20 | Talk 23:08, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- I've seen "Tierra Firme" used on some maps as an appareant equivalent for "Spanish Main". --Lazar Taxon (talk) 05:23, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

Switching syllables in two words to comic effect

I'm scratching my head here, because I should know this, and it's on the tip of my tongue... What's the term used when someone switches syllables in two words giving an amusing result? One of the anchors on the BBC just said "snifer riples" instead of "sniper rifles" and for the life of me, I can't think of the term. -- Александр Дмитрий (Alexandr Dmitri) (talk) 21:22, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Spoonerism. --Cookatoo.ergo.ZooM (talk) 21:27, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks, I knew that I knew it. -- Александр Дмитрий (Alexandr Dmitri) (talk) 21:49, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'd've said that was wrong. While some people use the word in an extended sense, a real spoonerism is a swap of the initial sounds -- in this case giving "riper snifles", which isn't bad either! The general term for a switching-around of sounds is metathesis, a word that (considering that the accent is on the "tath", not the "the") might be quite a bit easier to pronounce if some metathesis was applied to it... --Anonymous, 04:32 UTC, November 6, 2009.

- Wow! I've never seen two apostrophes in the same word. Is that grammatical? Clarityfiend (talk) 05:32, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Wiktionary describes that one as nonstandard. However, forecastle can be contracted with three apostrophes as "fo'c's'le", and this you will find in dictionaries. --Anonymous, 07:58 UTC, November 6, 2009.

- Interesting. It might not be suitable for professional writing (which may explain why it's described as "nonstandard"), but in a film script or play text, it could be very appropriate, and I'd've thought there's no better way of writing it. -- JackofOz (talk) 08:08, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Wiktionary describes that one as nonstandard. However, forecastle can be contracted with three apostrophes as "fo'c's'le", and this you will find in dictionaries. --Anonymous, 07:58 UTC, November 6, 2009.

- Wow! I've never seen two apostrophes in the same word. Is that grammatical? Clarityfiend (talk) 05:32, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'd've said that was wrong. While some people use the word in an extended sense, a real spoonerism is a swap of the initial sounds -- in this case giving "riper snifles", which isn't bad either! The general term for a switching-around of sounds is metathesis, a word that (considering that the accent is on the "tath", not the "the") might be quite a bit easier to pronounce if some metathesis was applied to it... --Anonymous, 04:32 UTC, November 6, 2009.

- Thanks, I knew that I knew it. -- Александр Дмитрий (Alexandr Dmitri) (talk) 21:49, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- I was curious what other languages called this. Most have their own native terms, but Turkish has just "spoonerism", and Polish has "spuneryzm", while Russian has "cпунеризм" (spunerizm). -- JackofOz (talk) 22:39, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you go to the spoonerism article and look at the links to other languages down the left-hand side (below the toolbox and stuff) you can see the names for whatever language currently have a WP article like this. (If you hover your mouse over each language, you should be able to see the name in a tooltip, status bar, or whatever, depending on your browser.) Some appear to be transliterations of the word "spoonerism", whereas others have their own words (like 'Antistrofe', etc.). rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 00:00, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I was curious what other languages called this. Most have their own native terms, but Turkish has just "spoonerism", and Polish has "spuneryzm", while Russian has "cпунеризм" (spunerizm). -- JackofOz (talk) 22:39, 5 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yep, that's how I got the results I reported above. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:55, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's the first time I heard of the word spuneryzm in Polish. If it's actually used, then only in specialist literature, but the common expression is gra półsłówek (literally: "play of half-words"), the spoonerism of which is sra półgłówek ("a dimwit is shitting"). Kpalion 194.39.218.10 (talk) 12:02, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Polish article acknowledges gra półsłówek. -- JackofOz (talk) 20:53, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's the first time I heard of the word spuneryzm in Polish. If it's actually used, then only in specialist literature, but the common expression is gra półsłówek (literally: "play of half-words"), the spoonerism of which is sra półgłówek ("a dimwit is shitting"). Kpalion 194.39.218.10 (talk) 12:02, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Yep, that's how I got the results I reported above. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:55, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Such things are also common parts of word games in other languages, such as Verlan and backslang —Preceding unsigned comment added by 130.56.65.25 (talk) 01:55, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Verlan and backslang both apply within a single word, whereas spoonerisms are generally switching sounds across two words. They also have different stylistic effects—spoonerisms are usually either slips-of-the-tongue, or jokes; verlan is a form of slang that is used in all seriousness. Back slang isn't really used except in a couple words that have already been lexicalized. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 02:48, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

November 6

Dumb words and expressions

Sort of related to the above question. There's a suite of words and expressions that have achieved currency here, originally as jokes or casual colloquialisms, but I'm hearing them more and more, and for some people they're almost at the point of replacing their originals. Examples include "ginormous" (a hybrid of "gigantic" and "enormous"), "Brisvegas" (apparently coined in a nod to Las Vegas when Brisbane gained its first casino), "Taswegian" for Tasmanian, "one foul swoop" (instead of "one fell swoop"). And many others. I don't know how one might classify these other than as "words and expressions that some dickheads constantly and irritatingly use". Is there a more professional way of describing them? -- JackofOz (talk) 04:33, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- They're a sort of mix of different word formation processes. Ginormous and Brisvegas are examples of blending and I know that one foul swoop is an eggcorn. I'm not sure what Taswegian is an example of; it might also be a blend.

- Unfortunately, there's no objective classification of your examples. One man's dick-head term is another man's vocabulary choice. What do you make of burger or the use of fridge for any refrigerator that isn't a Frigidaire? — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 05:13, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'd assume that "Taswegian" is a blend of "Tasmania" and "Glaswegian", suggested by the rhyme, although I don't know enough about mainland Australians' views of Tasmanians or English folks' views of Scots/Glaswegians to know whether there is some disparagement intended. Deor (talk) 05:30, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- 'Ginormous', 'Brisvegas', and 'Taswegian' are all meant to be humorous, or at least slightly amusing. Other words that would probably bother you, besides the aforementioned eggcorns, would be unnecessary or redundant back-formations, most notably orientate. —Akrabbimtalk 05:33, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'd always assumed - and the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary agrees - that fridge is simply an abreviation of refrigerator, not derived from a particular brand name. Thus presumably it might once have been ’fridge’, with apostrophes indicating the missing letters (much like influenza -> ’flu’ -> flu), although note that the fridge has an extra letter "d" in it. Mitch Ames (talk) 05:44, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I'd assume that "Taswegian" is a blend of "Tasmania" and "Glaswegian", suggested by the rhyme, although I don't know enough about mainland Australians' views of Tasmanians or English folks' views of Scots/Glaswegians to know whether there is some disparagement intended. Deor (talk) 05:30, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- "Ginormous" is a great word. I accidentally said that to one of my thesis advisors and he gave me a funny look, but didn't say anything, heh. Adding "Vegas" to a dinky little town is kind of common, and doesn't always have anything to do with a casino. I've heard the little town of Strathroy, Ontario referred to as "Strathvegas", for example (just as a sarcastic remark about how dinky and unglamourous it is). Adam Bishop (talk) 05:52, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I don't know where Adam Bishop is from (too lazy to look at userpages right now) but I've also heard this used for dinky little towns. Around here, Morrisville, Vermont (article?) is referred to as "MoVegas". Dismas|(talk) 06:22, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- 'Taswegian' seems to be used by Tasmanians and mainlanders alike, without anything pejorative intended. The first few times you hear it, it's slightly amusing, but after that ... I never knew whether it's connected to 'Glaswegian' or 'Norwegian', to both, or neither. There are far more people of Scots descent in Australia than of Norwegian descent, but apart from that I can't see any obvious connection between Glasgow and Tasmania. It seems to hook into an Australian penchant for finding ways of saying things in a non-standard way (but the new way then becomes the standard for a lot of people - which doesn't seem to matter because anything goes, as long as they're not being seen to be kowtowing to authority, except the peer group they wish to be associated with, i.e kowtow to). I'd guess that very few people who regularly use this expression have ever asked themselves "Why am I saying 'Taswegian', rather than 'Tasmanian', other than because other people are saying it?" -- JackofOz (talk) 05:57, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Sadly, "eggcorns" are all too common and annoying for language pedants (no names mentioned...) One that seems to have a fair deal of currency here that makes me wince every time is "the proof is in the pudding". As for the blendings/conflations, the constant reference to all political scandals as "X-gate" and all film industries as "X-llywood" (e.g., Bollywood, Wellywood) wears a bit thin after a while... Grutness...wha? 08:42, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- And "the devil is in the detail", and somebody has "signed off on" some proposal, and "we've done the hard yards". Oh, they're endlessly mindless and mindlessly endless. -- JackofOz (talk) 08:56, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Would that be a Tasmanian devil in those details? Come to think of it, has the use of "Tasmanian" as an adjective for an animal influenced the use of a different term to apply to the people? Contrast that with Canadian people and Canada geese. The latter are often mistakenly called Canadian geese, as if they were citizens, eh? As for words like "ginormous", that's kind of a portmanteau, as Lewis Carroll's Humpty Dumpty explained to Alice about words like "chortle", which is a combination of snort and chuckle. I looked for "fridge" in my old Webster's, and it's not there - so the unanswered question now is whether "fridge" came before or after "Frigidaire". ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 12:31, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Or independently? As a Briton I've seen plenty of fridges but never a Frigidaire, and it might explain the Webster's/Oxford difference. AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 14:38, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The wikipedia article, as well as this one[2] indicate that the Frigidaire was the first commercial refrigerator. Wiktionary is of no help, as it basically says "we need an answer". I've got a hunch that Frigidaire became synonymous with refrigerator, and hence "fridge" actually stands for both of them. Like "Victrola" as a synonym for "record player", even if it was a Columbia Grafonola, for example. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 14:53, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- But if the brand name didn't cross the Atlantic either as effectively or until much later, it's not inconceivable that the slang would develop independently of it. I've not heard of a Victrola either, but I'm not willing to rule out being born after their demise as a reason for that. AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 15:04, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Ironically, although "Hoover" is an American brand, it's never used by Americans as a generic term for a vacuum cleaner. 99.166.95.142 (talk) 17:11, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I brought up fridge as an example of a brand name being applied to similar products made by other companies. Other examples include xerox, iPod, and possibly Tivo. — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 23:23, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Ironically, although "Hoover" is an American brand, it's never used by Americans as a generic term for a vacuum cleaner. 99.166.95.142 (talk) 17:11, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- But if the brand name didn't cross the Atlantic either as effectively or until much later, it's not inconceivable that the slang would develop independently of it. I've not heard of a Victrola either, but I'm not willing to rule out being born after their demise as a reason for that. AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 15:04, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The wikipedia article, as well as this one[2] indicate that the Frigidaire was the first commercial refrigerator. Wiktionary is of no help, as it basically says "we need an answer". I've got a hunch that Frigidaire became synonymous with refrigerator, and hence "fridge" actually stands for both of them. Like "Victrola" as a synonym for "record player", even if it was a Columbia Grafonola, for example. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 14:53, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Or independently? As a Briton I've seen plenty of fridges but never a Frigidaire, and it might explain the Webster's/Oxford difference. AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 14:38, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Would that be a Tasmanian devil in those details? Come to think of it, has the use of "Tasmanian" as an adjective for an animal influenced the use of a different term to apply to the people? Contrast that with Canadian people and Canada geese. The latter are often mistakenly called Canadian geese, as if they were citizens, eh? As for words like "ginormous", that's kind of a portmanteau, as Lewis Carroll's Humpty Dumpty explained to Alice about words like "chortle", which is a combination of snort and chuckle. I looked for "fridge" in my old Webster's, and it's not there - so the unanswered question now is whether "fridge" came before or after "Frigidaire". ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 12:31, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- And "the devil is in the detail", and somebody has "signed off on" some proposal, and "we've done the hard yards". Oh, they're endlessly mindless and mindlessly endless. -- JackofOz (talk) 08:56, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think Jack is just noticing the normal progress of language. I don't think it's uniquely Australian, since I see it happening all the time in the UK. Even online: I now find I default to 'internets' rather than 'internet', which is slightly scary. Different language fits different registers, and a lot of these words and phrases that start out as clever jokes become gently humorous or light-hearted markers that indicate light-heartedness of the conversation. They aren't necessarily meant to be funny any more, just indicators that the conversation is in a lighter register. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 15:06, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- That makes a lot of sense, thanks 86.142. -- JackofOz (talk) 20:50, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

isn't the original question's classification of people who use such words itself dumb and irritating?--80.189.132.211 (talk) 17:08, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Perhaps. That's why I was after a more appropriate description of these forms of expression. -- JackofOz (talk) 20:50, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Is the following sentece acceptable?

I would like to know English native speakers opinion about the acceptability or grammaticality of the following sentence:

For what did you hit me?

Thanks 121.242.23.197 (talk) 11:43, 6 November 2009 (UTC)Vineet Chaitanya

- It's not really acceptable. You would say "What did you hit me for?" or "Why did you hit me?" instead. --Richardrj talk email 11:58, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Very technically, you aren't supposed to end a sentence with a preposition, such as for, but almost all native speakers I know ignore that rule when speaking. Falconusp t c 12:15, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- For very good reason, as there is not, and never has been, any such "rule". AndrewWTaylor (talk) 16:39, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Andrew beat me to this: it's not a rule. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 20:52, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Very technically, you aren't supposed to end a sentence with a preposition, such as for, but almost all native speakers I know ignore that rule when speaking. Falconusp t c 12:15, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

It's back-to-front, but in terms of being understandable it's fine. 194.221.133.226 (talk) 12:19, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- "For what did you hit me?" would be considered a funny way to say it, by someone being pretentious or something. There's a quote somewhere about Winston Churchill being criticized for his grammar, for ending a sentence with a preposition, and responding that that was a complaint "up with which I will not put!" ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 12:21, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Looking at Language Log for what they say on ending sentences with prepositions, I found this investigation of that anecdote.

- On topic, Language Log unsurprisingly says that it's perfectly fine to end sentences with prepositions. They quote The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (co-written by a Language Logger) saying the rule against ending sentences with prepositions is a made up one,

- "apparently created ex nihilo in 1672 by the essayist John Dryden, who took exception to Ben Jonson's phrase the bodies that those souls were frighted from (1611). Dryden was in effect suggesting that Jonson should have written the bodies from which those souls were frighted, but he offers no reason for preferring this to the original."[3]

- AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 14:27, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Churchill quote is fun, but apocryphal. -- JackofOz (talk) 22:34, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the sentence can be understood easily as it is than if it were grammatically correct. However, the sentence is grammatically incorrect. That is: a) if ‘for’ is a preposition, it cannot begin with an interrogation; b) if ‘for’ is a particle, it has to follow the verb in order to complete the sentence. Allthough if a deixis can be understood anaphorically as an ellipsis, but here again, the ‘wh’ interrogation ‘what’ is not a correct semantic substitution. Is this correct?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 17:46, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Either I'm misunderstanding you, or almost all of that comment is wrong. First of all, the sentence is not grammatically incorrect (see my other comment below). Secondly, a prepositional phrase can begin an interrogative sentence ("With whom did you go to the party?"—slightly uppity, but not awkward like the 'for what' sentence here). rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 21:07, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks for the comment. You are correct. However, a preposition does not always not act as a prepositional phrase, i.e. it can be of verb particle, ect. And the question and many comments here are about the treatment of ‘for what’ in the context of an interrogation. So my comment was that a preposition cannot begin an interrogation. However, a prepositional phrase does. Let me simplify this further. That is, ‘whom’ is a pronoun but ‘for what’ as it is mentioned here for ‘why’ is not a pronoun. Is this makes sense now, or do you have further comment?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 22:18, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- If something is acting as a particle, then it's not a preposition, it's a particle. And in any case, I don't see how that's relevant, as the "for what", "for what reason", "for whom", and whatever other thing you use in this sentence is a prepositional phrase. Structurally (i.e., from a word category point of view]], "for what" and "for whom" are absolutely no different. The difference is semantic: they're both prepositional phrases made up of a preposition head and a noun complement (in this case, a wh-word). rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 00:04, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Let me ask you this question. Can you begin an interrogation in English with any prepositions plus ‘why’ like, in why…, to why…, with why…, etc.? However, the answer is, yes, if there is pronoun like, what, whom, etc. Why do you think these are different?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 00:35, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Again, yes, a question can begin with a preoposition. More specifically, a question can begin with a prepositional phrase, and a prepositional phrase begins with a preposition. (For example: "At the football game, what did you eat?") rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 01:32, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Let me ask you this question. Can you begin an interrogation in English with any prepositions plus ‘why’ like, in why…, to why…, with why…, etc.? However, the answer is, yes, if there is pronoun like, what, whom, etc. Why do you think these are different?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 00:35, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- If something is acting as a particle, then it's not a preposition, it's a particle. And in any case, I don't see how that's relevant, as the "for what", "for what reason", "for whom", and whatever other thing you use in this sentence is a prepositional phrase. Structurally (i.e., from a word category point of view]], "for what" and "for whom" are absolutely no different. The difference is semantic: they're both prepositional phrases made up of a preposition head and a noun complement (in this case, a wh-word). rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 00:04, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks for the comment. You are correct. However, a preposition does not always not act as a prepositional phrase, i.e. it can be of verb particle, ect. And the question and many comments here are about the treatment of ‘for what’ in the context of an interrogation. So my comment was that a preposition cannot begin an interrogation. However, a prepositional phrase does. Let me simplify this further. That is, ‘whom’ is a pronoun but ‘for what’ as it is mentioned here for ‘why’ is not a pronoun. Is this makes sense now, or do you have further comment?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 22:18, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Either I'm misunderstanding you, or almost all of that comment is wrong. First of all, the sentence is not grammatically incorrect (see my other comment below). Secondly, a prepositional phrase can begin an interrogative sentence ("With whom did you go to the party?"—slightly uppity, but not awkward like the 'for what' sentence here). rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 21:07, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the sentence can be understood easily as it is than if it were grammatically correct. However, the sentence is grammatically incorrect. That is: a) if ‘for’ is a preposition, it cannot begin with an interrogation; b) if ‘for’ is a particle, it has to follow the verb in order to complete the sentence. Allthough if a deixis can be understood anaphorically as an ellipsis, but here again, the ‘wh’ interrogation ‘what’ is not a correct semantic substitution. Is this correct?--Mihkaw napéw (talk) 17:46, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Churchill quote is fun, but apocryphal. -- JackofOz (talk) 22:34, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Your first sentence doesn't really make sense to me: I'm not sure what you were trying to say. As to "what for": "what" by itself would not be the correct interrogative word, but "what for" means the same as "why", as does the archaic "wherefore". Using "what for", or "for what" as the sample sentence does, is unusual and sounds slightly arch, but is understandable and grammatical to a native speaker. However, it would be more natural (and pretty common) to separate them as "What did you hit me for?". 86.142.224.71 (talk) 18:35, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

it would seem that the passage is arranged so forth because it is archaic. the other would be for emphasis. 'For what' would ask the reason directly why you hit someone- for what gain, for what purpose. i would agree with the text on one point- that is the contextual use of 'wherefore' by Shakespeare in "Romeo and Juliet" which indeed asks why are you Romeo and not where Romeo is. 80.189.132.211 (talk) 20:38, 6 November 2009 (UTC) —Preceding unsigned comment added by 80.189.132.211 (talk) 20:36, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

It's possible to ask "For what reason did you hit me?", but "For what did you hit me?", while comprehensible, is ungrammatical. -- JackofOz (talk) 20:45, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- If you find "For what did you hit me?" ungrammatical, what do you think of the (twice) suggested "What did you hit me for?" -- 128.104.112.237 (talk) 20:57, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I have no issue with that. -- JackofOz (talk) 22:34, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- @JackofOz: it's not ungrammatical. It's just bad. The grammatical structure itself is fine (real ungrammatical would be something like "Max's of pizza" or "He's in the going").

- @ 128.104.112.237: it's just like people said, "what did you hit me for is fine". More specifically, "what for" (or "what...for") in English generally means the same as "why". But "for what" can't be extended like that. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 21:04, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- In many European languages, the question "why" is expressed as "what for"/"for what". English is a bit of an exception in having a distinct word. Vadför?, pourquoi?, почему?/зачто?, perche?, ¿porqué? So it would be quite natural for a learner to construct "For what...?". But in English For what did you hit me? would be understood as "for what thing" not "for what reason". It could be answered by "For a bet" or "For you kissing my girlfriend just now" or "For a hundred dollars". Not a usual construction. Sussexonian (talk) 21:47, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- "Not ungrammatical", Rjanag?: It's certainly not prescriptively grammatical, and it's such an unusual formulation that it would hardly have been recorded descriptively. So how does it get to be grammatical? You say it's grammatical but "bad"; I say it's comprehensible but ungrammatical. Maybe we're really agreeing without appearing to. -- JackofOz (talk) 22:34, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- It doesn't violate any grammatical rule. It has a well-formed prepositional phrase ("for what") acting as an adjunct, and the rest of its structure is also well-formed. The reason it's awkward is that the preposition phrase "for what" doesn't have the meaning you want it to. As a linguistic example, it would probably be written with a # mark rather than a *. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 00:00, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- I am a non-native of English, and I think the expression is a ellipsis in colloquial English. In grammar, it can be:

- For what purpose did you hit me?--purpose in question

- Why did you hit me?--reason in question. Nevill Fernando (talk) 04:18, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- No, it's not ellipsis. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 04:50, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

Thank you very much for the helpful comments. By the way, "For what did" occurs some 3 to 4 times in the corpus at http://www.americancorpus.org 121.242.23.197 (talk) 11:16, 8 November 2009 (UTC)Vineet Chaitanya

Medieval word meaning

What is the meaning and etymology of "discryued" and "discryuying"? 64.138.237.101 (talk) 13:17, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- What is the context? Looks like an alternate spelling of "describe", with a V instead of a B (and with the V spelled as U). Adam Bishop (talk) 13:40, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- In this[4] comparison between Old, Middle and Early Modern English (BCP), "discryued" is translated as "taxed".Alansplodge (talk) 13:47, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- There it's used in translating the Latin "ut describeretur universus orbis" and "haec descriptio prima facta est praeside Syriae Cyrino", referring to the taking of the census (for the purpose of taxation). The basic meaning of the Latin and the English is nonetheless "described" and "description"—although a better translation might be "enrolled" in this case. An example of a more normal use is The Assembly of Ladies, ll. 512–13: "Of this lady hir beauties to discryve / My konning is to symple verily." Deor (talk) 14:05, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Since the OP asked for the etymology, I should have added that it is, of course, from Latin describere, "to write down". Deor (talk) 21:14, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- There it's used in translating the Latin "ut describeretur universus orbis" and "haec descriptio prima facta est praeside Syriae Cyrino", referring to the taking of the census (for the purpose of taxation). The basic meaning of the Latin and the English is nonetheless "described" and "description"—although a better translation might be "enrolled" in this case. An example of a more normal use is The Assembly of Ladies, ll. 512–13: "Of this lady hir beauties to discryve / My konning is to symple verily." Deor (talk) 14:05, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- In this[4] comparison between Old, Middle and Early Modern English (BCP), "discryued" is translated as "taxed".Alansplodge (talk) 13:47, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks for the meanings and etymology. 64.138.237.101 (talk) 23:23, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Palatalization in English

Is it acceptable to pronounce the word “never” with a word-initial [nʲ]? --88.78.239.53 (talk) 14:45, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

WhatNot where I am (in the south of England). Algebraist 15:05, 6 November 2009 (UTC)- I think Algebraist means "Not where I am" (based on his/her edit summary). It would sound odd to me (a Northerner) too. AlmostReadytoFly (talk) 15:12, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I can't think of any variety of North American English that would have that pronunciation. In fact, it doesn't sound like a pronunciation I would associate with any part of the world where English is spoken as a native language. That pronunciation, however, is pretty common among people whose first language was Russian or another Slavic language. I think that most native speakers perceive it as a foreign accent. Marco polo (talk) 16:08, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's a hang up linked not to the n but to the e. In Russian the letter е in нет starts with a y sound (yes I know, I really should learn IPA). -- Александр Дмитрий (Alexandr Dmitri) (talk) 14:12, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- I can't think of any variety of North American English that would have that pronunciation. In fact, it doesn't sound like a pronunciation I would associate with any part of the world where English is spoken as a native language. That pronunciation, however, is pretty common among people whose first language was Russian or another Slavic language. I think that most native speakers perceive it as a foreign accent. Marco polo (talk) 16:08, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Which of the following words are pronounced with a word-initial [kʲ]: key, cue, coo? --88.78.228.228 (talk) 20:41, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Cue. --TammyMoet (talk) 21:20, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- These sound like homework questions. Check out palatalization and English phonology. — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 23:06, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Is it acceptable to pronounce the word “knee” with a word-initial [nʲ]? --88.78.2.122 (talk) 08:26, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Well a native English speaker wouldn't, if you did it would definitely mark you out as being foreign. Whether that equates to "acceptable" I really couldn't say.--TammyMoet (talk) 12:59, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Because English-speakers tend to blend their segments together, I wouldn't be surprised if English dialects that didn't undergo yod-dropping would have a palatalized coronal before the yod so that new would be pronounced [nʲju]. No guarantees, though. — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi] 01:37, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

These questions seem to be coming from the IP range 88.77.144.0 - 88.78.255.255, the same range where the repeated "Why can't **** be a German/English/whaterver word?" questions came from. --Kjoonlee 07:35, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

Term/name for different "flavors" of a (math) denotaton?

What is the term/name for a math (or other) character/symbol that has a modification to denote a relationship to a base character symbol? The most common example is the appostrophe or "prime" to denote a function's derivative: F = function; F' = the function's derivative. Another example would be a reduction or expansion of a variable:

I'm not sure if it was somewheres here in Wikipedia or an 1800's book from Google.Books, but I believe the word is "s___" or "sa___" something. ~Kaimbridge~ (talk) 15:56, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- In general language use, a symbol added to a letter, often to modify it, is a diacritic. For Unicode names of mathematical symbols, you can visit Code Charts, scroll down to the heading "Mathematical Symbols" in the second of four columns, and select from various charts. You might find what you are seeking. -- Wavelength (talk) 00:55, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- If forced to give it a name, I would call them modifiers. Diacritic is a better word for those which are indeed diacritics, like the above, but the prime symbol is not a diacritic. — Emil J. 14:31, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- The word modifier is used at SESSION 6: MODIFIERS AND MISCELLANEOUS SYMBOLS. -- Wavelength (talk) 16:32, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

subject vs citizen

Are the people who live in Canada subjects or citizens? Googlemeister (talk) 16:38, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I suppose in some arcane way we are subjects of the Queen, but otherwise there is normal Canadian citizenship. Adam Bishop (talk) 16:48, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I agree, they are subjects of the Queen and citizens of Canada. --Tango (talk) 17:32, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- In older Canadian passports( until the 1970s I think), it was written that "the holder is a British subject". This is no longer the case. --Xuxl (talk) 18:34, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- That would be until the British Nationality Act 1981.Sussexonian (talk) 21:54, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Bird law

what does it mean to refer to something as "bird law" —Preceding unsigned comment added by 82.43.88.201 (talk) 16:48, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

(Added title to question --Lesleyhood (talk) 17:17, 6 November 2009 (UTC))

- In what context? --Tango (talk) 17:32, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- A quick Google suggests either a firm of lawyers from Atlanta, Georgia[5] or law relating to birds (the feathered kind).Alansplodge (talk) 19:51, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

What does khazh mean?

What does the word khazh mean? Is it really an English word? It is used in something called a khazhsuit, which is a form of one-piece suit I think. The Great Cucumber (talk) 18:33, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Do you mean a Hazmat suit ? --Xuxl (talk) 18:35, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- No, I have taken the word litterary from the name of the group http://sports.groups.yahoo.com/group/snowkhazhsuit/ The Great Cucumber (talk) 19:15, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- And there is the slang term khazi, meaning lavatory. 86.142.224.71 (talk) 18:42, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Seems to be a Warcraft character[6]. Whether he wears a one-piece suit or not I don't know!!!!Alansplodge (talk) 19:44, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- And there is the fabric, khaki, which could certainly be used to make a one-piece suit if you wanted to. --Tango (talk) 19:58, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Are these guillemets?

《 》 . These are often used in Chinese (around book and movie titles, for instance), and are bigger than normal guillemets (which look like «» ). I'm just curious, is there a name for this punctuation? (Typing them in the search box just redirects to Bracket.) rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 19:46, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- They are given a mention in the article on Chinese punctuation, but unfortunately there is no name given. Maybe this could be added when you find one. --KageTora - SPQW - (影虎) (talk) 20:54, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Unicode has "300A 《 LEFT DOUBLE ANGLE BRACKET" and "300B 》RIGHT DOUBLE ANGLE BRACKET" (http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/U3000.pdf). -- Wavelength (talk) 21:36, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Chinese Wikipedia has the article zh:書名號, which discusses them. Maybe someone reading this Reference Desk page can provide a translation of the most relevant information. The one interlanguage link is to the English Wikipedia article Quotation mark, non-English usage, which seems to have no mention of them. -- Wavelength (talk) 00:25, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Hello? 書名號 literally means book name mark, and is used around the names of books, articles, journals, music, pictures etc.F (talk) 09:33, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- The Chinese Wikipedia has the article zh:書名號, which discusses them. Maybe someone reading this Reference Desk page can provide a translation of the most relevant information. The one interlanguage link is to the English Wikipedia article Quotation mark, non-English usage, which seems to have no mention of them. -- Wavelength (talk) 00:25, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

Rusyn people

I'm trying to find a list of people capable of speaking (preferably at a native level) Carpathian Rusyn and/or Pannonian Rusyn, either ancient kings, saints, politicians, modern writers, actors... --151.51.14.218 (talk) 20:56, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I suppose most of the people listed at Category:Rusyn people were able to speak, or at least understand, Rusyn. — Kpalion(talk) 22:18, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I fixed your category link, Kpalion - you have to put a colon before it in the link or it just adds this page to the category instead -Elmer Clark (talk) 23:33, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

good fricative luck!:) —Preceding unsigned comment added by 91.125.97.141 (talk) 16:23, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

Geographic appositives

I have a question about what you might call geographic appositives - putting a city's location immediately after its name, for example "Boston, Massachusetts", "San Francisco, California", "London, England" or "Paris, France". Is this a distinctively American thing? I ask because I often hear British people use the preposition "in" in these cases - for example, the Scottish-born talk show host Craig Ferguson will say that he's reading an email from "Springfield in Missouri" or "Toronto in Canada". --140.232.10.216 (talk) 21:22, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think it is mainly a North American thing (not just the USA but also Canada) to use these appositives outside of postal addresses, for example in conversation. These appositives do occur in postal addresses elsewhere in the Anglosphere, but occur less commonly in sentences elsewhere, at least in Britain. Marco polo (talk) 21:32, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- We do use them in Britain but they aren't needed as often since we don't duplicate place names as much as the US does. To us, "London" unambiguously refers to the British capital city, similarly with Paris. In the US there are often multiple places with the same name so specifying the state is necessary. --Tango (talk) 22:06, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the question is about exactly how the British specify the different places. For example, if it were necessary for a

BritisherBriton to distinguish Paris, Texas from any other Paris, would they tend to say "Paris, Texas" (U.S. style) or "Paris in Texas" or "Paris (the one in Texas)", or what? -- JackofOz (talk) 22:22, 6 November 2009 (UTC)- Britisher? What's wrong with Briton? 86.142.224.71 (talk) 23:23, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Nothing, really. I've changed it now. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:28, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- At least you didn't go with "pommy bastard". ;-) -- 128.104.112.237 (talk) 01:02, 11 November 2009 (UTC)

- Nothing, really. I've changed it now. -- JackofOz (talk) 00:28, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Britisher? What's wrong with Briton? 86.142.224.71 (talk) 23:23, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- I think the question is about exactly how the British specify the different places. For example, if it were necessary for a

- Any one of those could be used. The first one feels a little more formal to me. In informal speech you might hear something like "Paris (the Texas one, not the real one)" - we don't like to miss an opportunity to insult America! ;) --Tango (talk) 22:38, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- The British have never been known for their warm and cordial relations with the French (and vice-versa, I hasten to add). So it's interesting that they'd opportunistically pal up with the French when it comes to a chance to insult Americans. :) -- JackofOz (talk) 22:43, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- Don't forget Paris, Illinois! Regarding Texas, your typical Texan will say, "[city name], Texas" to anyone who's not a Texan, because they like to brag about being from Texas. And you wouldn't want to hear what they would probably say about "Gay Paris" in France. :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:08, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

- (after ec) FWIW, I'd say that - here in New Zealand, at least, but possibly elsewhere - the usual system is to use the appositive you mention but only when the place mentioned is a less well-known one either through importance/"well-knownness" (San Francisco vs San Francisco in Colombia) or through it being in this country (Hamilton vs [[Hamilton in Scotland or Hamilton, Ontario). We would talk about London (meaning the one in England), but of "London, Ontario" or "London in Canada". Oddly, it seems to be common, when needed, to refer to "Foo, X" when X is a subdividion of a country and "Foo in X" when X is a country, but that may just be me. Given that a surprising number of placenames are either unique or only have one really frequent usage, they're not used particularly often. There's seems little point in saying "Melbourne in Australia", "Los Angeles, California", or "Kathmandu in Nepal" if "Melbourne", "Los Angeles", or "Kathmandu" alone gets the point across 99.9% of the time. Grutness...wha? 23:19, 6 November 2009 (UTC)

Dialogue from All in the Family:

- Mike: A lot of places have the same names; like Portland, Maine, and Portland, Oregon.

- Gloria: Birmingham, England, and Birmingham, Alabama.

- Edith: New York, New York.

←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 00:26, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- In the UK, duplicate names often have a descriptive tag added: hence Newcastle-under-Lyme, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Newcastle Emlyn. In normal speach you would just say Newcastle unless you needed to clarify. You're right, I would say "in" too. Reading the para above I was thinking "Ah yes, and there's Portland in Dorset too..."Alansplodge (talk) 09:55, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

Maybe this is too far off on a tangent, but... when talking about the entire set of British islands, how common is for a place name to be exactly duplicated? I believe all US states and Canadian provinces expressly forbid exact duplication within their own borders. So, while there are many Springfields, there's only one Springfield, Illinois. What I'm getting at is that if it had been the norm for there to be a London, England and a London, Wales, and a London, Scotland, etc. that the UK would probably have adopted the same kind of pattern you see in NA. On the other hand, if it was the case that only one city on the entire set of islands could have a particular name, there'd obviously be no reason to use the comma-subregion form. Matt Deres (talk) 13:20, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- I must disagree. Go to http://factfinder.census.gov/ and look up Greenville in New York (Greenville, New York. There are two towns in different counties with that name (ignore the CDPs, as they are for statistical purposes with no government of their own). Additionally, you can have villages that have the same name of the town that they are in, even though they are not coterminous or may extend into neighboring towns (e.g., Mamaroneck). (New York is a messy state: Administrative divisions of New York) --Nricardo (talk) 15:12, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Their only purpose isn't to disambiguate between similarly named cities, they serve to give a more general idea of where the city is. The United States is huge - the chance that everybody you speak to has any idea of where a particular city is is pretty small, so we narrow it down by adding the state. It's probably less common in England, where there aren't any divisions similar to the American state (especially since England is about the size of some America states). —Akrabbimtalk 15:36, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are duplicates in Britain, but usually only for small places (there may be one big place with the name, which takes priority over the others, but there will rarely be more than one big place). Often it is due to them having very unoriginal names - for example, several new ports have been named Newport. --Tango (talk) 18:14, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- We actually have two Newports in Wales, the big one in the southeast, 3rd largest town in the country, and a little one in the southwest - though we might disambiguate them by using their not-at-all similar Welsh names, Newport/Casnewydd and Newport/Trefdraeth. -- Arwel Parry (talk) 01:11, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are loads of small places with identical names, but they are mostly places nobody has ever heard of anyway. The larger places that started out with the same names tend to have been differentiated later: apart from Newcastle, as above, there are examples like Northampton and Southampton; Poole and Welshpool; East Grinstead and West Grinstead. Examples of those that have not been differentiated are Newport, Gwent and Newport, Isle of Wight; various Whitchurches (Whitchurch, Hants; Whitchurch, Salop etc); Wellington, Salop and Wellington, Somerset; and for these the usage is the same as that in the US. Ehrenkater (talk) 23:03, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are a couple of duplicates that are notable, but mostly - as pointed out - only one will be well-known. Bangor (one in Wales, one in Northern Ireland) is one fairly notable one which has not been mentioned. Other than that - as Alansplodge points out - "disambiguators" are used, as in Kingston-upon-Thames and Kingston-upon-Hull. Grutness...wha? 23:47, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Another one, which illustrates another method of disambiguation, is the village of "Kingston near Lewes" in Sussex. Among lots of other Kingstons, there are also two plain "Kingston"s within about 20 miles of one another in Dorset Ehrenkater (talk) 16:53, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

- And it's not just settlements that get duplicate names. There are three River Rothers, for example (two of which are pretty close together). "Rother" apparently means "cattle", so it's not even just a local word for "river" (a lot of rivers are just called "river" in a local old language). --Tango (talk) 01:28, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- There are loads of small places with identical names, but they are mostly places nobody has ever heard of anyway. The larger places that started out with the same names tend to have been differentiated later: apart from Newcastle, as above, there are examples like Northampton and Southampton; Poole and Welshpool; East Grinstead and West Grinstead. Examples of those that have not been differentiated are Newport, Gwent and Newport, Isle of Wight; various Whitchurches (Whitchurch, Hants; Whitchurch, Salop etc); Wellington, Salop and Wellington, Somerset; and for these the usage is the same as that in the US. Ehrenkater (talk) 23:03, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- See List of the most common U.S. place names. -- Wavelength (talk) 00:59, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- The British Isles have ambiguous river names.

- River Inny, River Inny, Cornwall

- River Bann, River Bann (Wexford)

- River Blackwater, Essex, River Blackwater (River Loddon), River Blackwater (River Test), River Blackwater, Northern Ireland

- River Dee, Aberdeenshire, River Dee, Wales, River Dee (Lune), River Dee, Galloway, River Dee, County Louth

- River Don, Lancashire, River Don, South Yorkshire, River Don, Aberdeenshire

- River Eden, Cumbria, River Eden, Kent, River Eden, Fife

- River Avon, Devon, River Avon (Warwickshire), River Avon (Hampshire), River Avon (Bristol), River Avon (Falkirk), River Avon (Strathspey)

- River Tweed, River Tweed, England

- River Ouse, Yorkshire, River Ouse, Sussex

- River Wye, River Wye, Derbyshire, River Wye, Buckinghamshire

- -- Wavelength (talk) 06:49, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- As a minor but possibly useful point of usage, it's quite common practice in the UK, when referring to one of these name-duplicating rivers, to use the formulation "The Yorkshire Ouse", the Sussex Ouse", etc. This might also be used to refer to a particular section of a river that flows through more than one county. 87.81.230.195 (talk) 06:22, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

- Americans have the Red River and the Red River of the North. -- Wavelength (talk) 21:37, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

- [7]See this 2degrees ad on Cambridge, England, Cambridge, Australia and actual Cambridge. F (talk) 06:54, 10 November 2009 (UTC)

- See Wikipedia:Naming conventions (geographic names)#Disambiguation. -- Wavelength (talk) 23:02, 12 November 2009 (UTC)

So when the Beatles reported four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire, was that an Americanism? —Tamfang (talk) 00:55, 23 November 2009 (UTC)

November 7

English - "Metropolis" or something else

When we talk about colonies of some centuries ago, which is the correct english word to denote the country that they depended from? For example in the Americas, England for north america, Portugal for modern Brazil, or Spain for the rest of south america. I though that "Metropolis" was the word for it, but checking the article metropolis, which is mainly about a completely different thing, it seems that such a use would be outdated for this modern one. Is there then a better word for this concept, or should I use "metropolis" anyway? MBelgrano (talk) 01:09, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- I've never heard of metropolis meaning anything other than a big city. It was apparently used in the way you describe in Ancient Greece, but they were all about cities and city states, so they would have come from a specific city, rather than a country. "Polis" means city or town, so it wouldn't make sense to describe a country as a metropolis. I would say "homeland". When referring to them in the context of a now independent country a common term is "former colonial power". --Tango (talk) 01:19, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Metropolis is not an incorrect term, but I think Metropole would be clearer; however it's a rather specialized term that wouldn't be apparent to those who don't study history, geography, politics or international economics at least in an amateur sort of way. See Wikipedia's article on Metropole which should give you more of the information you're seeking. You might even put a WP:disambiguation note at the top of Metropolis to save others who might be making the same search from the confusion you just encountered. ¶ As for the substance of your question, there's no single term that's in common use: there are several, which differ slightly depending on the relationship. "Mother country" applies better to the home of colonies settled by those from the mother country (e.g. Britain in relation to the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand); and "colonial power" is a term that many Americans would not accept in regard to the U.S.'s relation to Cuba, Panama, Puerto Rico or the Philippines. "Imperial power" is often accurate, but again sometimes resented by its citizens, e.g. those of Russia or China. —— Shakescene (talk) 02:17, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Who would describe the US as Cuba's colonial power? The US never colonised Cuba, it was colonised by Spain... The US took control of it later, that wasn't a colonisation. --Tango (talk) 02:26, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Metropolis is not an incorrect term, but I think Metropole would be clearer; however it's a rather specialized term that wouldn't be apparent to those who don't study history, geography, politics or international economics at least in an amateur sort of way. See Wikipedia's article on Metropole which should give you more of the information you're seeking. You might even put a WP:disambiguation note at the top of Metropolis to save others who might be making the same search from the confusion you just encountered. ¶ As for the substance of your question, there's no single term that's in common use: there are several, which differ slightly depending on the relationship. "Mother country" applies better to the home of colonies settled by those from the mother country (e.g. Britain in relation to the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand); and "colonial power" is a term that many Americans would not accept in regard to the U.S.'s relation to Cuba, Panama, Puerto Rico or the Philippines. "Imperial power" is often accurate, but again sometimes resented by its citizens, e.g. those of Russia or China. —— Shakescene (talk) 02:17, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

I can't think of a commonly used neutral term for this, but "mother country" is a somewhat positive term for the relationship while "colonial masters" (referring to the people rather than the country) is a negative one. Or that's how they seem to me, anyway. --Anonymous, 03:02 UTC, November 7, 2009.

- I don't think either of those really fit, though. No native would refer to the colonizing country as his/her "mother country", while no settler would use "colonial master" to describe, well, themselves. Matt Deres (talk) 13:27, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- Indeed. I think maybe we just have to accept that we need to use different terms in different contexts. An additional context you didn't mention is the children of colonists - they might well feel a greater attachment to where they were born than where their parents (or grandparents or whatever) came from, so might not like the term "mother country". --Tango (talk) 18:17, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- In Swedish we use a word which translated would be "colonial power", so that Spain would have been the colonial power of Mexico e.g. Would that be a possible word for this in English? The Great Cucumber (talk) 13:47, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's not surprising to see a country referred to in English as "a colonial power", but we wouldn't say it was "the colonial power of" its colonies, in my experience. --Anonymous, 23:32 UTC, November 7, 2009.

- In Swedish we use a word which translated would be "colonial power", so that Spain would have been the colonial power of Mexico e.g. Would that be a possible word for this in English? The Great Cucumber (talk) 13:47, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- "Metropolitan France" is sometimes used to describe the European mainland core of France, perhaps this is where you got the idea of "Metropolis"? -- Arwel Parry (talk) 01:14, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- It's called that because it's a big-powerful-city part of France.

- It doesn't look like there's a term that wouldn't potentially connotate a city rather than a country. If it's necessary (and I doubt it is), we could coin a new word like metrokhoros (from χώρα, 'country'). — Ƶ§œš¹ [aɪm ˈfɻɛ̃ⁿdˡi]`

- Arwel means France, the country, as opposed to its overseas departments etc. (In that case it's probably because French uses "metropole" differently than English uses "metropolis".) Adam Bishop (talk) 03:17, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- something from Orson Welles and Citizen Kaine refers my mind to Metropolis- i'm kind of confused over it. As to colonial powers it again is context -we refer to colonies and colonial powers, etc, while those under such influence refer to us differently. the mother country is confusing and irksome as natives and colonials of those countries don't accept such a term: the natives to subsequent colonials, and colonials with further generations from settlement. some of this is exampled by Australians and Aborigines in Australia and native Americans and Americans in America, and everyone else between who is old or new to their shores .--91.125.97.141 (talk) 13:28, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

Latin ↔ Cyrillic converter for Tatar

I want a converter between the Latin and Cyrillic orthographies for the Tatar language. --88.78.13.59 (talk) 14:32, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

- This article is a bit poorly organized, but Tatar alphabet#Cyrillic version appears to have a table of Latin and Cyrillic orthography, which you could use for converting short things. As for an automated converter for larger texts...I don't know about any (although this is not really my area), but if you have any programming experience it would be relatively simple to create one. rʨanaɢ talk/contribs 18:26, 7 November 2009 (UTC)

November 8

Full stops

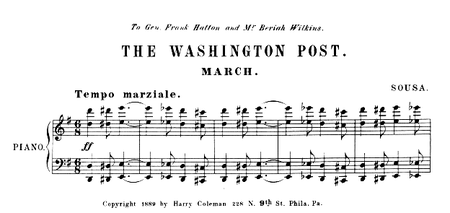

Why in 19th century book covers or sheet music have full stops just after short phrases or titles, such as the "Meno mosso." in  ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Mikespedia (talk • contribs) 01:58, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Mikespedia (talk • contribs) 01:58, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

And not just in German, either. I don't know why, but it's a practice that continued into the 20th century and his since faded. Comiskey Park used to say "Home of the White Sox." with that period at the end,[8] which was dropped over time when the park would get repainted from time to time. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 05:56, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- It was common in the mid-19th century for people to put a period after everything. A store sign might say "DRY GOODS." for example. -- Mwalcoff (talk) 06:16, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- I suspect that the "why" of it at this point would be speculative. Maybe the rise in literacy made folks feel compelled to put a punctuation mark at the end of every complete thought, even if it wasn't a sentence. And it wasn't just with sheet music. Newspaper headlines read that way also. Papers of the day might have several heading lines for one article, each a little smaller and more detailed than the previous, leading the reader toward the story - and with a period at the end of each of the little headlines, whether they were proper sentences or not. I can get a sampling of this from a 1970s book called The Scrapbook History of Baseball, which is a collection of newspaper articles reprinted as if they were cut and pasted into a scrapbook. This continued into the 20th century. Here's an example from late September of 1908, illustrating the Fred Merkle incident. It also illustrates the editorializing that routinely turned up in news stories - and this was written by the Chicago writer, Charles Dryden. Caps and punctuation reproduced exactly, except for [my comments] inserted, and each sentence is a different headline: GAMES ENDS IN TIE [separate line] MAY GO TO CUBS. "Bush League" Baserunner [Merkle] Costs Giants a 2 to 1 Victory in the Ninth. DISPUTE UP TO PULLIAM. [National League President] Chicago Claims Forfeit on Account of Interference; O'Day [umpire] Says "No Contest." Standings of the Clubs. [standings follow] BY CHARLES DRYDEN. [story follows - with several little embedded headlines, all ending with periods.] ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 06:53, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- Because the book is "anecdotal", it's hard to tell precisely how the practice changed, but within a few years, true headlines were generally omitting the periods, and the periods were only being used with sub-headlines that were complete sentences. By about 1920, even the complete-sentence sub-headlines were generally omitting the periods. Newswriting by the 1910s was getting to be much "punchier" and modern vs. the stodgy writing style of the 19th century, and that may have fed into this change over time. The last example I'm seeing of using the period at the end of a sub-headline was in 1938. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 07:03, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- With all due respect, there was a pretty clear purpose to the full-stops when headlines were written as nearly-complete sentences: they separated one sentence from another. It's true that typography (size, font and weight) do all that now, but it's also true that earlier headlines and sub-headlines were often stacked over four, six or ten lines. The reason is clear, even if different reasons are applied today. The more interesting question is why titles and names on signs used to be followed by periods/full-stops when the names or titles ("Main Street.", "The Royal Crown.", "Post Office.", "Fine Groceries.", "The Raven.", even newspapers' own logos, such as the "The Wall Street Journal.") were clearly not full sentences. I think that some of my teachers in primary/elementary school in London and New England in the 1950's told us to put a full-stop/period at the end of a title. If you're writing in manuscript and not centering or underlining your titles (or if the title takes up a whole line), a closing stop helps to distinguish the title from the beginning of the first sentence; it also introduces the spoken or mental pause that follows a title. —— Shakescene (talk) 07:39, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- When Bill O'Reilly says "with all due respect..." just before he rips into a guest, I feel as if he ought to say, "with all undue respect..." :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:11, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- We were also told in school to capitalize all the words in a title except for articles and conjunctions (unless they were the first word of the title). Now we've gone to the other extreme, capitalizing the first word only except for proper names, as if the title were a sentence. Maybe wikipedia should revive the practice of adding periods to those kinds of phrases. :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:14, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- When Bill O'Reilly says "with all due respect..." just before he rips into a guest, I feel as if he ought to say, "with all undue respect..." :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:11, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- With all due respect, there was a pretty clear purpose to the full-stops when headlines were written as nearly-complete sentences: they separated one sentence from another. It's true that typography (size, font and weight) do all that now, but it's also true that earlier headlines and sub-headlines were often stacked over four, six or ten lines. The reason is clear, even if different reasons are applied today. The more interesting question is why titles and names on signs used to be followed by periods/full-stops when the names or titles ("Main Street.", "The Royal Crown.", "Post Office.", "Fine Groceries.", "The Raven.", even newspapers' own logos, such as the "The Wall Street Journal.") were clearly not full sentences. I think that some of my teachers in primary/elementary school in London and New England in the 1950's told us to put a full-stop/period at the end of a title. If you're writing in manuscript and not centering or underlining your titles (or if the title takes up a whole line), a closing stop helps to distinguish the title from the beginning of the first sentence; it also introduces the spoken or mental pause that follows a title. —— Shakescene (talk) 07:39, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- Because the book is "anecdotal", it's hard to tell precisely how the practice changed, but within a few years, true headlines were generally omitting the periods, and the periods were only being used with sub-headlines that were complete sentences. By about 1920, even the complete-sentence sub-headlines were generally omitting the periods. Newswriting by the 1910s was getting to be much "punchier" and modern vs. the stodgy writing style of the 19th century, and that may have fed into this change over time. The last example I'm seeing of using the period at the end of a sub-headline was in 1938. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 07:03, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- I suspect that the "why" of it at this point would be speculative. Maybe the rise in literacy made folks feel compelled to put a punctuation mark at the end of every complete thought, even if it wasn't a sentence. And it wasn't just with sheet music. Newspaper headlines read that way also. Papers of the day might have several heading lines for one article, each a little smaller and more detailed than the previous, leading the reader toward the story - and with a period at the end of each of the little headlines, whether they were proper sentences or not. I can get a sampling of this from a 1970s book called The Scrapbook History of Baseball, which is a collection of newspaper articles reprinted as if they were cut and pasted into a scrapbook. This continued into the 20th century. Here's an example from late September of 1908, illustrating the Fred Merkle incident. It also illustrates the editorializing that routinely turned up in news stories - and this was written by the Chicago writer, Charles Dryden. Caps and punctuation reproduced exactly, except for [my comments] inserted, and each sentence is a different headline: GAMES ENDS IN TIE [separate line] MAY GO TO CUBS. "Bush League" Baserunner [Merkle] Costs Giants a 2 to 1 Victory in the Ninth. DISPUTE UP TO PULLIAM. [National League President] Chicago Claims Forfeit on Account of Interference; O'Day [umpire] Says "No Contest." Standings of the Clubs. [standings follow] BY CHARLES DRYDEN. [story follows - with several little embedded headlines, all ending with periods.] ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 06:53, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- So, when did the prescriptivist stance that you only put a full stop after a complete sentence arise? Or was the idea always there, and simply not paid attention to by anyone? Were there any early writers who would consistently put a full stop after a complete sentence only? --84.239.160.214 (talk) 07:59, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

In the second example above, the stops actually convey useful information I didn't have before. We all refer to "The Washington Post March", which plays along with the credits at the end of the film, All the President's Men. But the sheet music shows that the title was "The Washington Post", and that it was a march (and not, say, a waltz or a polka). —— Shakescene (talk) 07:46, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- The article The Washington Post (march) discusses that, and it's true that the periods erase any question that the title is simply "The Washington Post". However, "March" being on a separate line and in smaller print also conveys that point. Also notice that everything else has a period after it also, including "Sousa." Styles change, and it's often easier to track the "when" than the "why". I have a photo of my company's building from ca. 1910 that shows its name in big bold letters - followed by a period. Just one of those things that no one questioned, apparently. Like when did people stop the common practicing of writing "&c." and begin write "etc." all the time, despite the fact they are precisely the same thing - while continuing to use "&" (stylized "et") for "and"? ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:09, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

The U.S. Declaration of Independence ends its first line with a period, even though the title is centered. Curiously, the second line ends in a comma. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 08:19, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- It might be of interest to note that many people in China learning English are taught to (or at least they all pick up the habit of) write a period/full stop at the end of individual words -- for example, if they're writing out a single English word (or possibly even their name in English), they put a full stop at the end. --71.111.194.50 (talk) 17:45, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

i would put the words into context: that of music. having had an Italian music teacher, Miss Pecorini, for ten years as a teacher, I know that these short command phrases were in vogue at her time-she was 65/70 years old- and maybe at the time of the music sheet itself. learning to play the piano is guided by short terse statements from a teacher or written commands on the script. It would be no different than instructions on a road or in the air- complexity confuses the situation. the periods may mark a stop from one command to the next.--91.125.97.141 (talk) 10:23, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

MEANING OF £ IS ?

MEANING OF £ IS ?MRLuCkY7777 (talk) 11:15, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- Pound sterling. Karenjc 11:25, 8 November 2009 (UTC)

- Historically the same symbol was also used for the Italian lira and for other countries' pounds (major currency units): Australia, Ireland etc. -Ehrenkater (talk) 17:03, 9 November 2009 (UTC)

- From "libra", meaning "scales" or "weight". A number of terms for money, in various languages, use words that have to do with weight. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 11:37, 8 November 2009 (UTC)