Fallingwater: Difference between revisions

m →Structural problems: very minor grammatical correction |

|||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

Fallingwater's [[structural engineering|structural]] system includes a series of bold [[reinforced concrete]] cantilevered balconies; however, the house had problems from the beginning. Pronounced [[deflection#Structural engineering|sagging]] of the concrete cantilevers was noticed as soon as formwork was removed at the construction stage.<ref name="FallingDown">{{cite news |url=http://www.structuremag.org/archives/2006/Falling%20Water/FallingWater.pdf |format=PDF|title=Repair and Retrofit: Is Falling Water Falling Down? |publisher=Structure Magazine |author=Silman, Robert and John Matteo |date=2001-07-01 |accessdate=2007-09-20}}</ref> |

Fallingwater's [[structural engineering|structural]] system includes a series of bold [[reinforced concrete]] cantilevered balconies; however, the house had problems from the beginning. Pronounced [[deflection#Structural engineering|sagging]] of the concrete cantilevers was noticed as soon as formwork was removed at the construction stage.<ref name="FallingDown">{{cite news |url=http://www.structuremag.org/archives/2006/Falling%20Water/FallingWater.pdf |format=PDF|title=Repair and Retrofit: Is Falling Water Falling Down? |publisher=Structure Magazine |author=Silman, Robert and John Matteo |date=2001-07-01 |accessdate=2007-09-20}}</ref> |

||

The [[Western Pennsylvania Conservancy]] conducted an intensive program to preserve and restore Fallingwater.From 1988–2004 New York City-based architecture and engineering firm WASA/Studio A was responsible for the materials conservation of Fallingwater. During this time, the firm reviewed original construction documents and subsequent repair documents and reports; evaluated conditions and probes; analyzed select materials; designed the re-roofing and re-waterproofing of roofs and terraces; specified the restoration for original steel casement windows and doors; reconstructed failed concrete reconstructions; restored the masonry; analyzed interior paint finishes; specified interior paint removal methodology and re-painting; designed repair methods for concrete and stucco; and developed a new coating system for the concrete. WASA/Studio A produced a graphic condition assessment consisting of 178 measured CAD drawings and a master plan for restoration. Once the team had prepared the first of four phases of construction documents, these were distributed to and commented on by a group of seven peer reviewers, culminating in a five-hour public presentation at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. |

The [[Western Pennsylvania Conservancy]] conducted an intensive program to preserve and restore Fallingwater. From 1988–2004 New York City-based architecture and engineering firm WASA/Studio A was responsible for the materials conservation of Fallingwater. During this time, the firm reviewed original construction documents and subsequent repair documents and reports; evaluated conditions and probes; analyzed select materials; designed the re-roofing and re-waterproofing of roofs and terraces; specified the restoration for original steel casement windows and doors; reconstructed failed concrete reconstructions; restored the masonry; analyzed interior paint finishes; specified interior paint removal methodology and re-painting; designed repair methods for concrete and stucco; and developed a new coating system for the concrete. WASA/Studio A produced a graphic condition assessment consisting of 178 measured CAD drawings and a master plan for restoration. Once the team had prepared the first of four phases of construction documents, these were distributed to and commented on by a group of seven peer reviewers, culminating in a five-hour public presentation at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. |

||

In order to develop the new concrete coating system, WASA/Studio A evaluated three different environmentally-contained paint stripping methods and approximately 120 samples applied by four different paint manufacturers over a one-year paint testing period. Re-roofing and re-waterproofing involved working closely with three different roofing membrane manufacturers, all of which agreed to provide warranties. In fact with the completion of re-roofing and re-waterproofing, the building is virtually leak-free for the first time in its history. Issues of condensation under the roofing membranes resulting from the lack of a thermal break. <ref>"Fallingwater Part 2: Materials-Conservation Efforts at Frank Lloyd Wright's Masterpiece," by Pamela Jerome, Norman Weiss and Hazel Ephron © 2006 Association for Preservation Technology International (APT).http://www.jstor.org/pss/40004684</ref> |

In order to develop the new concrete coating system, WASA/Studio A evaluated three different environmentally-contained paint stripping methods and approximately 120 samples applied by four different paint manufacturers over a one-year paint testing period. Re-roofing and re-waterproofing involved working closely with three different roofing membrane manufacturers, all of which agreed to provide warranties. In fact with the completion of re-roofing and re-waterproofing, the building is virtually leak-free for the first time in its history. Issues of condensation under the roofing membranes resulting from the lack of a thermal break. <ref>"Fallingwater Part 2: Materials-Conservation Efforts at Frank Lloyd Wright's Masterpiece," by Pamela Jerome, Norman Weiss and Hazel Ephron © 2006 Association for Preservation Technology International (APT).http://www.jstor.org/pss/40004684</ref> |

||

Revision as of 14:38, 5 February 2010

Fallingwater | |

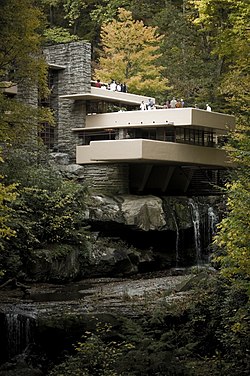

The famous view of Fallingwater | |

| Location | Mill Run, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Pittsburgh |

| Built | 1934-1937 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Modernism |

| Visitation | about 135,000 |

| NRHP reference No. | 74001781[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 23, 1974 |

| Designated NHL | May 23, 1966[2] |

Fallingwater, also known as the Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. Residence, is a house designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1934 in rural southwestern Pennsylvania, 50 miles southeast of Pittsburgh. The house was built partly over a waterfall in Bear Run at Rural Route 1 in the Mill Run section of Stewart Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in the Laurel Highlands of the Allegheny Mountains.

Hailed by Time magazine shortly after its completion as Wright's "most beautiful job,"[3] it is also listed among Smithsonian magazine's Life List of 28 places "to visit before ...it's too late."[4] Fallingwater was featured in Bob Vila's A&E Network production, Guide to Historic Homes of America.[5] It was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966.[2] In 1991, members of the American Institute of Architects named the house the "best all-time work of American architecture" and in 2007, it was ranked twenty-ninth on the list of America's Favorite Architecture according to the AIA.

History

Edgar Kaufmann Sr. was a successful Pittsburgh businessman and founder of Kaufmann's Department Store. His son, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., studied architecture under Wright briefly.

Edgar Sr. had been prevailed upon by his son and Wright to itemize the cost of his utopian model city. When completed, it was displayed at Kaufmann’s Department Store and Wright was a guest in the Kaufmann home, “La Tourelle”, a French Norman masterpiece that celebrated Pittsburgh architect Benno Janssen (1874-1964) had created in the stylish Fox Chapel suburb in 1923 for Edgar J. Kaufmann. The Kaufmanns and Wright were enjoying refreshments at La Tourelle when Wright, who never missed an opportunity to charm a potential client, said to Edgar Jr. in tones that the elder Kaufmanns were intended to overhear, “Edgar, this house is not worthy of your parents…” The remark spurred the Kaufmanns' interest in something worthier. Fallingwater would become the end result.

The Kaufmanns owned some property outside Pittsburgh with a waterfall and some cabins. When the cabins at their camp had deteriorated to the point that something had to be rebuilt, Mr. Kaufmann contacted Wright.

In November 1934, Wright visited Bear Run. He asked for a survey of the area around the waterfall, which he received in March 1935. This survey was prepared by Fayette Engineering Company of Uniontown, Pennsylvania and included all of the boulders, trees and topography. It took 9 months for his ideas for the site to crystallize into a design which was quickly sketched up by Wright in time for a visit by Kaufmann to Taliesin in September 1935.[6][7] It was then that Kaufmann first became aware that Wright’s design was for the house to be built above the falls,[8] rather than below the falls as he had expected.[9]

Design and construction

The structural design for Fallingwater was undertaken by Wright in association with Mendel Glickman and William Wesley Peters who had been responsible for the design of the revolutionary columns which were a feature of Wright’s design for the Johnson Wax Headquarters.

Preliminary plans were issued to Kaufmann for approval on October 15, 1935,[10] after which Wright made a further visit to the site and provided a cost estimate to his client. In December 1935 an old rock quarry was opened to the west of the water to provide the stones needed for the house’s walls. Wright only made periodic visits to the site during construction, instead assigning Robert Mosher who was one of his apprentices as his permanent on-site representative.[10] The final working drawings were issued by Wright in March 1936 with work beginning on the bridge and the main house in April 1936.

The construction was plagued by conflicts between Wright, Kaufmann and the construction contractor. The view of the building is such that the falls can be heard when inside the building, but the falls are visible only when standing on the balcony on the topmost floor. This type of geometrical architecture mystery has even puzzled the architect Wright himself.

Kaufmann had Wright’s design reviewed by a firm of consulting engineers as he doubted whether Wright had sufficient experience with using reinforced concrete. Upon receiving their report Wright took offense and immediately requested Kaufmann to return his drawings and indicated he was withdrawing from the project. Kaufmann apologized and the engineer’s report was subsequently buried within a stone wall of the house.[10]

After a visit to the site, Wright in June 1936 rejected the concrete work for the bridge, which had to be rebuilt.

For the cantilevered floors Wright and his team used integral upside-down beams with the flat slab on the bottom forming the ceiling of the space below. The contractor, Walter Hall, who was also an engineer, produced independent computations and argued for increasing the reinforcement in the first floor’s slab. Wright rebuffed the contractor. While some sources state that it was the contractor who quietly doubled the amount of reinforcement,[11] according to others,[10] it was at Kaufmann’s request that his consulting engineers redrew Wright’s reinforcing drawings and doubled the amount of steel specified by Wright. This additional steel not only added weight to the slab but was set so close together that the concrete often could not properly fill in between the steel, which weakened the slab. In addition, the contractor did not build in a slight upward incline in the formwork for the cantilever to compensate for the settling and deflection of the cantilever once the concrete had cured and the formwork was removed. As a result, the cantilever developed a noticeable sag. Upon learning of this, Wright temporarily replaced Mosher with Edgar Tafel.[12]

The consulting engineers with Kaufmann’s approval arranged for the contractor to install a supporting wall under the main supporting beam for the west terrace. When Wright discovered it on a site visit he had Mosher discreetly remove the top course of stones. When Kaufmann later confessed to what had been done, Wright showed him what Mosher had done and pointed out that the cantilever had held up for the past month under test loads without the wall’s support.[13]

In October 1937 the main house was completed.

Cost

At the time of its construction, the house cost a total of $155,000.[14] broken down as follows:[6] house $75,000, finishing and furnishing $22,000, guest house, garage and servants quarters $50,000, architect's fee $8,000. Accounting for inflation, this translates to about $2.4 million in 2010 dollars.[15]

Use of the house

Fallingwater was the family's weekend home from 1937 to 1963. In 1963, Kaufmann, Jr. donated the property to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. In 1964 it was opened to the public as a museum and nearly six million people have visited the house since (as of January 2008). It currently hosts more than 120,000 visitors each year.[14]

Style

Fallingwater stands as one of Wright's greatest masterpieces both for its dynamism and for its integration with the striking natural surroundings. Wright's passion for Japanese architecture was strongly reflected in the design of Fallingwater, particularly in the importance of interpenetrating exterior and interior spaces and the strong emphasis placed on harmony between man and nature. Tadao Ando once stated: "I think Wright learned the most important aspect of architecture, the treatment of space, from Japanese architecture. When I visited Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, I found that same sensibility of space. But there was the additional sounds of nature that appealed to me."[16]

The extent of Wright's genius in integrating every detail of this design can only be hinted at in photographs. This organically designed private residence was intended to be a nature retreat for its owners. The house is well-known for its connection to the site: it is built on top of an active waterfall which flows beneath the house. The fireplace hearth in the living room is composed of boulders found on the site and upon which the house was built — one set of boulders which was left in place protrudes slightly through the living room floor. Wright had initially intended that these boulders would be cut flush with the floor, but this had been one of the Kaufmann family's favorite sunning spots, so Mr. Kaufmann insisted that it be left as it was. The stone floors are waxed, while the hearth is left plain, giving the impression of dry rocks protruding from a stream.

Integration with the setting extends even to small details. For example, where glass meets stone walls, there is no metal frame; rather, the glass is caulked directly to the stone. There are stairways directly down to the water. And in the "bridge" that connects the main house to the guest and servant building, a natural boulder drips water inside, which is then directed back out. Bedrooms are small, some even with low ceilings, perhaps to encourage people outward toward the open social areas, decks, and outdoors.

The active stream (which can be heard constantly throughout the house), immediate surroundings, and locally quarried stone walls and cantilevered terraces (resembling the nearby rock formations) are meant to be in harmony, in line with Wright's interest in making buildings that were more "organic" and which thus seemed to be more engaged with their surroundings. Although the waterfall can be heard throughout the house, it can't be seen without going outside. The design incorporates broad expanses of windows and the balconies are off main rooms giving a sense of the closeness of the surroundings. The experiential climax of visiting the house is an interior staircase leading down from the living room allowing direct access to the rushing stream beneath the house.

Wright's views of what would be the entry have been argued about; still, the door Wright considered the main door is tucked away in a corner and is rather small. Wright's idea of the grand facade for this house is from the perspective of all the famous pictures of the house, looking up from downstream, viewing the opposite corner from the main door.

On the hillside above the main house is a four-car carport (though the Kaufmanns had requested a garage), servants' quarters, and a guest bedroom. This attached outbuilding was built one year later using the same quality of materials and attention to detail as the main house. Just uphill from it is a small 6-foot-deep swimming pool, continually fed by natural water, which then overflows to the river below. Through a visual trick comparing the swimming pool walls with the landscape beyond, the swimming pool appears not to be level; it is, in fact, level. The carport was, at the direction of Kaufmann, Jr., eventually enclosed for use by Fallingwater visitors, who generally gather there at the end of guided tours. Kaufmann, Jr. designed the interiors himself, but to specifications found in other Fallingwater interiors designed by Wright.

Structural problems

Fallingwater's structural system includes a series of bold reinforced concrete cantilevered balconies; however, the house had problems from the beginning. Pronounced sagging of the concrete cantilevers was noticed as soon as formwork was removed at the construction stage.[17]

The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy conducted an intensive program to preserve and restore Fallingwater. From 1988–2004 New York City-based architecture and engineering firm WASA/Studio A was responsible for the materials conservation of Fallingwater. During this time, the firm reviewed original construction documents and subsequent repair documents and reports; evaluated conditions and probes; analyzed select materials; designed the re-roofing and re-waterproofing of roofs and terraces; specified the restoration for original steel casement windows and doors; reconstructed failed concrete reconstructions; restored the masonry; analyzed interior paint finishes; specified interior paint removal methodology and re-painting; designed repair methods for concrete and stucco; and developed a new coating system for the concrete. WASA/Studio A produced a graphic condition assessment consisting of 178 measured CAD drawings and a master plan for restoration. Once the team had prepared the first of four phases of construction documents, these were distributed to and commented on by a group of seven peer reviewers, culminating in a five-hour public presentation at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh.

In order to develop the new concrete coating system, WASA/Studio A evaluated three different environmentally-contained paint stripping methods and approximately 120 samples applied by four different paint manufacturers over a one-year paint testing period. Re-roofing and re-waterproofing involved working closely with three different roofing membrane manufacturers, all of which agreed to provide warranties. In fact with the completion of re-roofing and re-waterproofing, the building is virtually leak-free for the first time in its history. Issues of condensation under the roofing membranes resulting from the lack of a thermal break. [18]

The structural work under supervision of Louis D. Astorino of Pittsburgh was completed in 2002. This involved a detailed study of the original design documents, observing and modeling the structure's behavior, then developing and implementing a repair plan.

The study indicated that the original structural design and plan preparation had been rushed and the cantilevers had significantly inadequate reinforcement. As originally designed by Wright, the cantilevers would not have held their own weight.[11]

The 2002 repair scheme involved temporarily supporting the structure; careful, selective, removal of the floor; post-tensioning the cantilevers underneath the floor; then restoring the finished floor.[11]

Given the humid environment directly over running water, the house also had mold problems. The elder Kaufmann called Fallingwater "a seven-bucket building" for its leaks, and nicknamed it "Rising Mildew".[19]

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved 2006-03-15.

- ^ a b "Fallingwater". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ "Usonian Architech". TIME magazine Jan. 17, 1938. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ "Smithsonian Magazine - Travel - The Smithsonian Life List". Smithsonian magazine January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ^ Bob Vila (1996). ""Guide to Historic Homes of America."" (html). A&E Network.

- ^ a b McCarter, page 59.

- ^ Toker, Franklin (2003). Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's Most Extraordinary House. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4026-4.

- ^ "[W]hy did the client say that he expected to look from his house toward the waterfall rather than dwell above it?" Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House, New York: Abbeville Press, p. 31. (ISBN 0-89659-662-1)

- ^ McCarter, page 7.

- ^ a b c d McCarter, page 12.

- ^ a b c Feldman, Gerard C. (2005). "Fallingwater Is No Longer Falling". STRUCTURE magazine (September): pp. 46–50.

- ^ McCarter, pages 12 and 13.

- ^ McCarter, pages 13.

- ^ a b Plushnick-Masti, Ramit (2007-09-27). "New Wright house in western Pa. completes trinity of work". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ "The Inflation Calculator".

- ^ "Tadao Ando, 1995 Laureate: Biography" (PDF). The Hyatt Foundation. 1995. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ Silman, Robert and John Matteo (2001-07-01). "Repair and Retrofit: Is Falling Water Falling Down?" (PDF). Structure Magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ^ "Fallingwater Part 2: Materials-Conservation Efforts at Frank Lloyd Wright's Masterpiece," by Pamela Jerome, Norman Weiss and Hazel Ephron © 2006 Association for Preservation Technology International (APT).http://www.jstor.org/pss/40004684

- ^ (Brand 1995)

Bibliography

- Trapp, Frank (1987). Peter Blume. Rizzoli, New York.

- Hoffmann, Donald (1993). Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater: The House and Its History (2nd ed.). Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27430-6.

- Brand, Stewart (1995). How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013996-6.

- McCarter, Robert (2002). Fallingwater Aid (Architecture in Detail). Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-4213-3.

Further reading

- Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House (Abbeville Press 1986)

- Robert McCarter, Fallingwater Aid (Architecture in Detail) (Phaidon Press 2002)

- Franklin Toker, Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E. J. Kaufmann, and America's Most Extraordinary House (Knopf, 2005)

- Lynda S. Waggoner and the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Fallingwater: Frank Lloyd Wright's Romance With Nature (Universe Publishing 1996)

External links

- Official website - includes visiting information

- Information and photographs of Fallingwater

- Photo Visit of Fallingwater

- Fallingwater architectural review

- Fallingwater at Great Buildings including 3D model

- YouTube video walkthru of Fallingwater

- http://www.mocpages.com/moc.php/31871 LEGO Fallingwater

- Fallingwater en Perspectiva A project painted on site.

- Fallingwater - La Casa De La Cascada - A short computer graphic movie (in English) featuring the Frank Lloyd Wright masterpiece by Cristóbal Vila, 2007.

- Images of Fallingwater

- Plans and models