Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor: Difference between revisions

→Marketed drugs: added hyperforin and adhyperforin, found in the herb Hypericum perforatum |

→Marketed drugs: added more info about other marketed drugs |

||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

===Marketed drugs=== |

===Marketed drugs=== |

||

Some people/studies have suggested that [[venlafaxine]] (Effexor) behaves as a SNDRI if extremely high dosages are taken.<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10434156?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=4&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed</ref><ref>http://www.emedexpert.com/facts/venlafaxine-facts.shtml</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7856622?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=5&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed</ref><ref>http://www.springerlink.com/content/9uxed20x6cm76e88/</ref> |

Some people/studies have suggested that [[venlafaxine]] (Effexor) behaves as a SNDRI if extremely high dosages are taken.<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10434156?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=4&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed</ref><ref>http://www.emedexpert.com/facts/venlafaxine-facts.shtml</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7856622?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=5&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed</ref><ref>http://www.springerlink.com/content/9uxed20x6cm76e88/</ref> Venlafaxine is an [[Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor|SNRI]] that [[reuptake inhibitor|inhibits reuptake]] of [[serotonin]] and [[norepinephrine]]. It is theorized that the [[norepinephrine transporter]] also recycles a small amount of [[dopamine]], and therefore any [[norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor]] such as venlafaxine is also a very weak [[dopamine reuptake inhibitor]]. Theoretically this means other [[Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor|SNRI]]s also function as very weak [[dopamine reuptake inhibitor]]s and are therefore SNDRIs in extremely high doses as well, but taking such high doses would probably not be safe. |

||

[[Sibutramine]] (Meridia, Reductil) is a functional SNDRI, although this is a diet pill for obesity and not marketed as an antidepressant. Due to safety concerns, it has been suspended in the UK<ref>{{cite web | url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/8473555.stm | title=Top obesity drug sibutramine being suspended | accessdate=2010-01-22}}</ref> and [[EU]]<ref>{{de icon}} Sibutramin-Vertrieb in der Europäischen Union ausgesetzt [http://www.abbott.de/content/e17/e127/e15940/index_de.html]. [[Abbott Laboratories]] in Germany. [[Press Release]] 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2010-01-27</ref>, and is also under review by the [[FDA]]<ref>[http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm191650.htm Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride)], [[U.S. Food and Drug Administration], November 20, 2009</ref> and the [[European Medicines Agency]]<ref>[http://www.ema.europa.eu/pdfs/human/referral/sibutramine/3940810en.pdf Press Release], European Medicines Agency, January 21, 2010</ref>. |

|||

[[Sibutramine]] (Meridia, Reductil) is a functional SNDRI, although this is a diet pill for obesity and not marketed as an antidepressant. |

|||

[[Bupropion]] is an [[Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor|NDRI]] that is combined with SSRIs in refractory patients.<ref>{{Cite pmid|16165100}}</ref> This commonly prescribed drug combination is equivalent to an SNDRI. There are a number of other [[Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor|NDRI]]s such as [[Methylphenidate]] that could also be combined with SSRIs to similarly achieve the effects of an SNDRI. However, many [[Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor|NDRI]]s are potentially dangerous [[stimulant]]s with abuse potential, so such combinations should be limited to the [[Norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor|NDRI]]s which are considered safe. |

|||

[[Bupropion]] is a poor DRI, that is combined with SSRIs in refractory patients.<ref>{{Cite pmid|16165100}}</ref> |

|||

The [[medicinal herb]] ''[[Hypericum perforatum]]'' (St. John's Wort) contains two SNDRIs as [[active constituent]]s: [[hyperforin]] and [[adhyperforin]].<ref name="pmid11518085">{{cite journal | author = Müller WE, Singer A, Wonnemann M | title = Hyperforin--antidepressant activity by a novel mechanism of action | journal = Pharmacopsychiatry. | year = 2001 | pmid = 11518085 }}</ref><ref name="pmid9718074">{{cite journal |author=Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharya SK, Wonnemann M, Singer A, Müller WE |title=Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of hypericum extracts |journal=Life Sci. |volume=63 |issue=6 |pages=499–510 |year=1998 |pmid=9718074 |doi=10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00299-9}}</ref> Hyperforin and adhyperforin are [[reuptake inhibitor]]s of [[monoamine]]s such as [[serotonin]], [[norepinephrine]], [[dopamine]], [[GABA]], and [[glutamate]], and they exert these effects [[allosteric inhibition|allosterically]] by binding to and [[receptor theory|activating]] the [[transient receptor potential]] [[cation channel]] [[TRPC6]].<ref name="pmid9718074"/><ref name="pmid17666455">{{cite journal |author=Leuner K, Kazanski V, Müller M, ''et al'' |title=Hyperforin--a key constituent of St. John's wort specifically activates TRPC6 channels |journal=The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology |volume=21 |issue=14 |pages=4101–11 |year=2007 |month=December |pmid=17666455 |doi=10.1096/fj.07-8110com |url=}}</ref> Activation of TRPC6 induces the entry of [[calcium]] (Ca<sup>2+</sup>) and [[sodium]] (Na<sup>+</sup>) into the [[Cell (biology)|cell]], which causes this inhibition of monoamine reuptake.<ref name="pmid17666455"/> |

The [[medicinal herb]] ''[[Hypericum perforatum]]'' (St. John's Wort) contains two SNDRIs as [[active constituent]]s: [[hyperforin]] and [[adhyperforin]].<ref name="pmid11518085">{{cite journal | author = Müller WE, Singer A, Wonnemann M | title = Hyperforin--antidepressant activity by a novel mechanism of action | journal = Pharmacopsychiatry. | year = 2001 | pmid = 11518085 }}</ref><ref name="pmid9718074">{{cite journal |author=Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharya SK, Wonnemann M, Singer A, Müller WE |title=Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of hypericum extracts |journal=Life Sci. |volume=63 |issue=6 |pages=499–510 |year=1998 |pmid=9718074 |doi=10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00299-9}}</ref> Hyperforin and adhyperforin are [[reuptake inhibitor]]s of [[monoamine]]s such as [[serotonin]], [[norepinephrine]], [[dopamine]], [[GABA]], and [[glutamate]], and they exert these effects [[allosteric inhibition|allosterically]] by binding to and [[receptor theory|activating]] the [[transient receptor potential]] [[cation channel]] [[TRPC6]].<ref name="pmid9718074"/><ref name="pmid17666455">{{cite journal |author=Leuner K, Kazanski V, Müller M, ''et al'' |title=Hyperforin--a key constituent of St. John's wort specifically activates TRPC6 channels |journal=The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology |volume=21 |issue=14 |pages=4101–11 |year=2007 |month=December |pmid=17666455 |doi=10.1096/fj.07-8110com |url=}}</ref> Activation of TRPC6 induces the entry of [[calcium]] (Ca<sup>2+</sup>) and [[sodium]] (Na<sup>+</sup>) into the [[Cell (biology)|cell]], which causes this inhibition of monoamine reuptake.<ref name="pmid17666455"/> |

||

Revision as of 13:09, 26 February 2010

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (January 2010) |

A serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI), or triple reuptake inhibitor (TRI), is a drug which simultaneously acts as a reuptake inhibitor for the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline), and dopamine, by blocking the action of the serotonin transporter (SERT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and dopamine transporter (DAT), respectively. This in turn leads to increased extracellular concentrations of these neurotransmitters and therefore an increase in serotonergic, noradrenergic or adrenergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmission.

Applications

Major depression is the foremost reason supporting the need for development of an SNDRI.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is now recognized as the leading cause of disability[2].

By the year 2020 depression has been projected to be 2nd only to ischemic heart disease as the leading global burden of disease (GBD).

Additional indications are for alcoholism,[8] cocaine addiction,[9] obesity,[10] ADHD,[11] PD and AD.

There is some evidence that antidepressants can be used in the treatment of other conditions, for example chronic pain[12].

Various diseases including schizophrenia and cancer are more easy to target using a multitude of mechanisms of activity[13][14].

Indeed, the selective COX-2 inhibitor Vioxx possessed more side effects than those that were less selective.

Currently the best-selling drugs are engineered with the prospect of curing a diseased PNS.[3] CNS drugs

For example, Lipitor accounted for 23% of Pfizer's revenues in 2004, Norvasc was 9%, whereas Zoloft netted 6.5%.[15]

This review synthetizes the existing literature for a group of compounds that has not yet made it on to the market.

Examples

Clinical candidates

None of the SNDRIs have been approved for marketing, but several are under active development and are currently in clinical trials. If they are successful, they could become available within the next few years.

- Actually in clinical trials

- DOV-102,677 • DOV-21,947 • DOV-216,303

- NS-2359 (GSK-372,475) • Tesofensine (NS-2330)

- SEP-225,289 http://www.sepracor.com/products/sep225289.html

- Under (preclinical) development

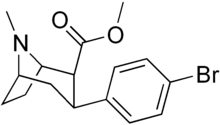

- Sepracor has also patented the RS enantiomer of sertraline (see tametraline).

- PRC200-SS

- JNJ-7925476

- AMRI U.S. patent 7,163,949 US application 20,080,318,997 US application 20,090,048,443

| Compd[5] | [3H]5HT | [3H]NA | [3H]DA | SERT | NET | DAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS-1 | 14 | 12.7 | 22.4 | 1.3 | 8.2 | 21.6 |

| CNS-2 | 24 | 12.6 | 24.6 | 3.5 | 10.4 | 31.7 |

| Duloxetine | 2.8 | 3.2 | 202 | 0.6 | 3.9 | 888 |

- Discontinued candidates

- Brasofensine (NS-2214) (for Parkinson's disease).

- Ro8-4650

- BTS 74,398

Research compounds

- Lilly LR-5182 WF-23

- Naphthyl milnacipran analog[16] (also nmda receptor antagonist)

- 3,3-disubstituted pyrrolidine[17]

- Indatraline (Lu 19-005)

- JZ-IV-10 (16e)

- Methylnaphthidate (HDMP-28)

- Naphyrone (O-2482)

- D-161

- 3,4-disubstituted pyrrolidines[18]

- Mazindol analogs[19]

The above listed compounds constitute only a small percentage of the known triple reuptake inhibitors that are available, and generally have been picked for use in research or possible clinical development because of favourable pharmacokinetic characteristics or higher bioavailability which made them stand out from the much larger pool of structurally diverse compounds that show similar high binding affinity for all three target monoamine transporter proteins in vitro.

Marketed drugs

Some people/studies have suggested that venlafaxine (Effexor) behaves as a SNDRI if extremely high dosages are taken.[20][21][22][23] Venlafaxine is an SNRI that inhibits reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. It is theorized that the norepinephrine transporter also recycles a small amount of dopamine, and therefore any norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor such as venlafaxine is also a very weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Theoretically this means other SNRIs also function as very weak dopamine reuptake inhibitors and are therefore SNDRIs in extremely high doses as well, but taking such high doses would probably not be safe.

Sibutramine (Meridia, Reductil) is a functional SNDRI, although this is a diet pill for obesity and not marketed as an antidepressant. Due to safety concerns, it has been suspended in the UK[24] and EU[25], and is also under review by the FDA[26] and the European Medicines Agency[27].

Bupropion is an NDRI that is combined with SSRIs in refractory patients.[28] This commonly prescribed drug combination is equivalent to an SNDRI. There are a number of other NDRIs such as Methylphenidate that could also be combined with SSRIs to similarly achieve the effects of an SNDRI. However, many NDRIs are potentially dangerous stimulants with abuse potential, so such combinations should be limited to the NDRIs which are considered safe.

The medicinal herb Hypericum perforatum (St. John's Wort) contains two SNDRIs as active constituents: hyperforin and adhyperforin.[29][30] Hyperforin and adhyperforin are reuptake inhibitors of monoamines such as serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, GABA, and glutamate, and they exert these effects allosterically by binding to and activating the transient receptor potential cation channel TRPC6.[30][31] Activation of TRPC6 induces the entry of calcium (Ca2+) and sodium (Na+) into the cell, which causes this inhibition of monoamine reuptake.[31]

Background

There are several lines of evidence linking the role of monoamines (ie 5HT/NE/DA) to depression. Firstly, when reserpine was first imported to the westernized continent from India, it was shown that this agent precipitated a depressive syndrome.[32] It was further shown that reserpine causes a depletion of monoamine concentrations in the brain.

The first antidepressant agents (the MAOIs and the TCAs) were discovered entirely by serendipity.[33] Amphetamines and opioids had in fact been used before these, although they were phased-out with the advent of newer, less addictive, medications.[34]

Thus, it was discovered that both MAOIs and TCAs alleviate the depressive syndrome through enhancing the synaptic abundance of extracellular monoamine neurotransmitters.[33]

TCAs

Julius Axelrod discovered that the TCA drug imipramine potently inhibits the reuptake of NE in the heart.[35][36] Although all TCAs have a dopaminergic component, with the exception of amineptine mostly all of the TCAs are SNRI-type.

TCAs have unwanted antimuscarinic, antihistamine, and ion channel blocking properties, among others.[4]

Hypersomnia is one of the biggest let-downs with these agents, although cardiotoxicity has also been reported. Hypotension is another potentially serious side-effect that can be measured with analytical instrumentation.

Agents such as desipramine and related secondary amines are NET selective whereas the tertiary amines and particularly clomipramine are more SERT selective.

Imipramine is of course the oldest of the TCAs, although its ancestry is actually traced back to neuroleptic agents such promazine.[33]

Milnacipran, mianserin, and mirtazapine are all efforts to try to circumvent the side effects of the TCAs, while retaining the therapeutic benefits of these agents. Collectively, these are known as the tetracyclics (TeCAs).

MAOIs

Phenelzine and tranylcypromine are the archetypal MAOIs used for depression, although others have been developed such as the RIMAs and subtype selective (c.f. clorgyline).[33] More recently the Emsam patch has also been approved for the treatment of depression. MAOIs that are B-type selective do not effect 5-HT or NE concentrations and are mostly DA selective. However, to get any therapeutic benefit out of selegiline in the treatment of depression, a high dose (>30 mg) is needed so that the MAO-A enzyme can become inhibited.[37]

MAOIs bind to molecular targets such as enzymes other than the relevant MAO enzymes, and notably, they also paradoxically decrease norepinephrine and epinephrine levels, potentially resulting in orthostatic hypotension, fatigue and lethargy, and somewhat inhibited therapeutic response. SNDRIs, on the other hand, do the opposite, in concept making them considerably more effective and tolerable in comparison.

Dietary restrictions are a problem, partciularly with phenezine, whereas tyramine rich foods must be avoided. Interestingly, the effects of tranylcypromine start immediately and do not require several weeks/months before a therapeutic response is felt.

MAOIs are "alkylating agents" because they form a covalent bond with the active site of the relevant molecular target/s.

The permanency of these agents is an attractive property.

Another draw-back is the report that irreversible MAOIs are reported to be hepatotoxic, further underscoring the need for alternative therapies.

Nonselective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) can be expected to provide some insight into what a TRI will feel like. Although the mechanism of action is different, both types of agents elevate synaptic concentrations of neurotransmitters.

Serotonergic

Following on from the discovery of the "classical" antidepressants, the next step was the design of SSRIs.[38]

SSRIs have been a huge commercial success, and have generated more monetary gains than any other antidepressant.[citation needed]

Eli Lilly and Company were the first company to bring an antidepressant into the mainstream.[39] Prozac (fluoxetine) is a drug that had been worked on for over 20 years before finally gaining acceptance. Zimelidine was withdrawn, due to some strange side-effects.

Paxil (paroxetine), Zoloft (sertraline), Luvox (fluvoxamine), Celexa (citalopram), and Lexapro (escitalopram) are other SSRIs.

Although all these agents generated a lot of money, most are now generic.

Patients treated with SSRIs who had shown remission relapsed after treatment with p-chloro-phenylalanine. Alternatively, depriving the diet of tryptophan also causes relapse.

SSRIs are much safer than "classical" antidepressants, especially in cases of overdose. They are less hazardous to use in polypharmacy, and dietary restrictions are largely unnecessary. Furthermore, they are not addictive, and actually reduce cocaine intake.

There are 14 different types of 5-HT receptor,[40] which is more than the number of DA and NE receptors combined. The role of 5-HT has been best characterized for the 5-HT2A receptors, stimulation of which causes hallucinations as is the case with LSD. 5-HT is involved in the regulation of mood and emotions, appetite, the processing of pain, etc.

SSRIs are the first line of treatment, but they have a number of drawbacks and their efficacy is actually inferior to the classical antidepressants, i.e. TCAs and MAOIs. Therapeutic lag,[41] fatigue and hypersomnia, lack of efficacy,[42] nausea and vomiting, anxiety, and apathy, among other adverse effects, have all been reported.

Noradrenergic

With the advent of the SSRIs, NE has received relatively less attention in the treatment of depression, although it is still a valid strategy.[37]

Schildkraut postulated a "catecholamine hypothesis of depression" that is still often referenced.

A stastical link between energizing antidepressants like the NRIs and suicide attempts redirected efforts in favor of SSRIs (c.f. Celexa).[5]

Evidence that SNRIs are more efficacious than SSRIs in the treatment of depression is at best, weak, with the former only producing marginally superior response rates over the latter (approximately 5% greater at most).[43]

Selective NRIs on the market for the treatment of depression is limited to reboxetine and viloxazine.

The NET is a recognized target in the treatment of ADHD, as evidenced by the introduction of atomoxetine, a selective NRI.

Dopaminergic

A shortage of mesolimbic dopamine is actually one of the cardinal cues for triggering depression.[7][44][45][46]

Major depression in PD accounts for as many as 50% of those diagnosed, and treatment of depressed patients with a variety of dopamine agonists has an antidepressant response.

This results in anhedonia whereas an excess amount of dopamine is causes elation.

There is strong evidence that psychostimulants are in fact valid and powerful antidepressant agents in many people.[47][48]

Dopaminergic neurotransmission serves an important role in motivation and concentration, as well as in decision making, and counteracting fatigue.

Dopaminergic agents used on their own have a number of side-effects, used in conjunction with a SSRI it is possible to counterbalance this.

Locomotion is another example, with serotonin inhibiting it and dopamine facilitating it.

SSRIs are antipsychotic in that microdialysis studies in the field of stimulant abuse have shown that SSRIs inhibit the ability of DRIs to elevate extracellular dopamine concentrations in the brains of animals.

An interesting observation is that SSRIs can cause hypersomnia in some people, which is the exact opposite of what is experienced when taking psychostimulant compounds such as amphetamine.

There is a reciprocal interaction between serotonin and dopamine, in that like a seesaw, the effect of one counterbalances the other.[49]

Enantiospecificity

Most[which?] experts are of the opinion that a "single molecule" is to be preferred.[5]

This is worth noting, since many drugs are sold as a racemic pair of enantiomers, e.g. tramadol, mdma, etc.

Racemic drugs take more time to develop, because each enantiomer must be treated as a separate drug entity, and tested separately.

Consider the following TUI's that are treated as three different compounds: DOV 216303 (±), DOV 21947 (+), and DOV 102677 (–).

For citalopram and also Ritalin, only one of the enantiomers contributed to the phramacological activity.

In contrast, the DOV compounds, and also e.g. indatraline and sertraline, both isomers have pharmacological activity.

Froimowitz said the eutomer was preferable to the racemate based on toxicological factors, but maybe too expensive to foot Lacoste?

Reciprocal Interactions

Not all authors agree with this. As example the most selective of the SSRI's, escitalopram has documented efficacy that is superior to the SNRIs venlafaxine and duloxetine.

Just because an agent possesses activity at all 3 of the MA transporters, does not mean that it cannot still possess additional activities at other CNS sites.[6][50] The list of possible sites of action and involvement of neurotransmitters (etc) is very long and cannot easily be accommodated in a document of the size. Ronald Duman provided explanations on the effect of neuro/thymoleptics on sites that are efferent from the transporter pumps. He goes into detail in delineating the involvement of secondary messenger molecules, G proteins, and the entire milieu of intracellular signaling pathways, and how this effects signal transduction. A SNDRI thus can serve as a point of entry into dictating the nuclear transcription of biomolecules at a cellular level (c.f "CREB"). Additionally, hypercortisolemia is among the more cardinal symptoms that constitutes the depressive syndrome,[51] and a competent antidepressant must be able to normalize this. In contrast hypocortisolemia constitutes PTSD.

Relation to Cocaine

Cocaine is an extremely short-acting SNDRI, that also exerts auxiliary pharmacological actions on other receptors. Cocaine is a relatively "balanced" inhibitor, although it is the facilitation of dopaminergic neurotransmission that endows it with reinforcing and addictive properties. Many of the SNDRIs currently being developed have varying degrees of similarity to cocaine in terms of their chemical structure. There has been speculation over whether the new SNDRIs will have an abuse potential like cocaine does. New drugs are rigorously screened in animal self-administration protocols. It is advantageous that a medicine is at least weakly reinforcing because it can serve to retain addicts in the treatment programmes.

- "...limited reinforcing properties in the context of treatment programs may be advantageous, contributing to improved patient compliance and enhanced medication effectiveness."[52]

Cocaine itself unfortunately has some serious defects in terms of its cardiotoxicity.[53] Thousands of users of cocaine are admitted to emergency units in the USA every year because of this, and so the development of safer substitute drugs could potentially have significant benefits for public health.

Note: 5-HT is not required for antidepressant activity to be exerted, but dopaminergic activity is essential.[7]

See also

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19110199, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19110199instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19426122, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19426122instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19702555, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19702555instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19587855, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19587855instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17714023, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17714023instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16522330, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16522330instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18690111, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18690111instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17908267, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17908267instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.009, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.06.009instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18089843, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18089843instead. - ^ http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00467428

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17325229, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17325229instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15060530, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15060530instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19110195, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19110195instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.309.5735.728, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.309.5735.728instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17350257, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17350257instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18954985, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18954985instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11354356, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11354356instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12213054, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12213054instead.Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12213053, please use {{cite journal}} with|pmid=12213053instead. - ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10434156?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=4&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed

- ^ http://www.emedexpert.com/facts/venlafaxine-facts.shtml

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7856622?ordinalpos=1&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_SingleItemSupl.Pubmed_Discovery_RA&linkpos=5&log$=relatedreviews&logdbfrom=pubmed

- ^ http://www.springerlink.com/content/9uxed20x6cm76e88/

- ^ "Top obesity drug sibutramine being suspended". Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ Template:De icon Sibutramin-Vertrieb in der Europäischen Union ausgesetzt [1]. Abbott Laboratories in Germany. Press Release 2010-01-21. Retrieved 2010-01-27

- ^ Early Communication about an Ongoing Safety Review of Meridia (sibutramine hydrochloride), [[U.S. Food and Drug Administration], November 20, 2009

- ^ Press Release, European Medicines Agency, January 21, 2010

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16165100, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16165100instead. - ^ Müller WE, Singer A, Wonnemann M (2001). "Hyperforin--antidepressant activity by a novel mechanism of action". Pharmacopsychiatry. PMID 11518085.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Chatterjee SS, Bhattacharya SK, Wonnemann M, Singer A, Müller WE (1998). "Hyperforin as a possible antidepressant component of hypericum extracts". Life Sci. 63 (6): 499–510. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00299-9. PMID 9718074.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Leuner K, Kazanski V, Müller M; et al. (2007). "Hyperforin--a key constituent of St. John's wort specifically activates TRPC6 channels". The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 21 (14): 4101–11. doi:10.1096/fj.07-8110com. PMID 17666455.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1192/bjp.113.504.1237, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1192/bjp.113.504.1237instead. - ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19442174, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19442174instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18956529, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18956529instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18543469, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18543469instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16402124, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16402124instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16475956, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16475956instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17017959, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17017959instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16121130, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16121130instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18476671, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18476671instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15837601, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15837601instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19022290, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19022290instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17588546, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17588546instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16413172, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16413172instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16566899, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16566899instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17339521, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17339521instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17338594, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17338594instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18425966, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18425966instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16475959, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16475959instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16429123, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16429123instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16797263, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16797263instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11408518, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11408518instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19463023, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19463023instead.