Sarcoidosis: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

==Diagnosis== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often a matter of exclusion. To exclude sarcoidosis in a case presenting with pulmonary symptoms might involve [[chest X-ray]], [[CT scan]] of chest, [[PET scan]], |

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often a matter of exclusion. To exclude sarcoidosis in a case presenting with pulmonary symptoms might involve [[chest X-ray]], [[CT scan]] of chest, [[PET scan]], CT-guided biopsy, mediastinoscopy, open lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, endobronchial ultrasound and [[endoscopic ultrasound]] with [[FNA]] of mediastinal [[lymph nodes]]. [[Tissue]] from [[biopsy]] of lymph nodes is subjected to both [[flow cytometry]] to rule out cancer and special stains ([[acid fast]] bacilli stain and [[Gömöri methenamine silver stain]]) to rule out [[microorganisms]] and [[fungi]]. [[Angiotensin-converting enzyme]] blood levels are used in diagnosis and monitoring of sarcoidosis.<ref>http://www.labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/ace/test.html</ref> |

||

==Investigations== |

==Investigations== |

||

Revision as of 06:32, 8 March 2010

| Sarcoidosis | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Hematology, dermatology, pulmonology, ophthalmology |

| Frequency | 0.16% |

Sarcoidosis (sarc = flesh, -oid = like, -osis = a process), also called sarcoid or Besnier-Boeck disease, is a multisystem granulomatous inflammatory disease[1] characterized by non-caseating granulomas (small inflammatory nodules). The cause of the disease is still unknown. Virtually any organ can be affected; however, granulomas most often appear in the lungs or the lymph nodes. Symptoms usually appear gradually but can occasionally appear suddenly. The clinical course generally varies and ranges from asymptomatic disease to a debilitating chronic condition that may lead to death.

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis most commonly affects young adults of both sexes, although studies have reported more cases in females. Incidence is highest for individuals younger than 40 and peaks in the age-group from 20 to 29 years; a second peak is observed for women over 50.[2][3]

Sarcoidosis occurs throughout the world in all races with an average incidence of 16.5/100,000 in men and 19/100,000 in women. The disease is most prevalent in Northern European countries, and the highest annual incidence of 60/100,000 is found in Sweden and Iceland. In the United States, sarcoidosis is more common in people of African descent than Caucasians, with annual incidence reported as 35.5 and 10.9/100,000, respectively.[4] Sarcoidosis is less commonly reported in South America, Spain, India, Canada, and Philippines.

The differing incidence across the world may be at least partially attributable to the lack of screening programs in certain regions of the world and the overshadowing presence of other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis, that may interfere with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis where they are prevalent.[2] There may also be differences in the severity of the disease between people of different ethnicity. Several studies suggest that the presentation in people of African origin may be more severe and disseminated than for Caucasians, who are more likely to have asymptomatic disease.[5]

Manifestation appears to be slightly different according to race and sex. Erythema nodosum is far more common in men than in women and in Caucasians than in other races. In Japanese patients, ophthalmologic and cardiac involvement are more common than in other races.[3]

Sarcoidosis is one of the few pulmonary diseases with a higher prevalence in non-smokers.

Types

Sarcoidosis may be divided into the following types:[6]: 708–11

Signs and symptoms

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease that can affect any organ. Common symptoms are vague, such as fatigue unchanged by sleep, lack of energy, weight loss, aches and pains, arthritis, dry eyes, swelling of the knees, blurry vision, shortness of breath, a dry hacking cough or skin lesions. Sarcoidosis and cancer may mimic one another, making the distinction difficult.[8] The cutaneous symptoms vary, and range from rashes and noduli (small bumps) to erythema nodosum or lupus pernio. It is often asymptomatic.

The combination of erythema nodosum, bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and arthralgia is called Löfgren syndrome. This syndrome has a relatively good prognosis.

Renal, liver (including portal hypertension), heart[9] or brain involvement may cause further symptoms and altered functioning. Sarcoidosis affecting the brain or nerves is known as neurosarcoidosis.

Although cardiac involvement is present in 20% to 30% of patients with sarcoidosis, only about 5% patients with systemic sarcoidosis are symptomatic.[10]

The presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis can range from asymptomatic conduction abnormalities to fatal ventricular arrhythmia.[11] Myocardial sarcoidosis can be a rare cause of sudden cardiac death.[12][13]

Manifestations in the eye include uveitis, uveoparotitis, and retinal inflammation, which may result in loss of visual acuity or blindness.

The combination of anterior uveitis, parotitis, VII cranial nerve paralysis and fever is called uveoparotid fever, and is associated with Heerfordt-Waldenstrom syndrome. (D86.8)

Sarcoidosis of the scalp presents with diffuse or patchy hair loss.[6]: 762

Sarcoidosis is a possible cause of Bell's palsy.

Granulomatous disease may cause atelectasis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often a matter of exclusion. To exclude sarcoidosis in a case presenting with pulmonary symptoms might involve chest X-ray, CT scan of chest, PET scan, CT-guided biopsy, mediastinoscopy, open lung biopsy, bronchoscopy with biopsy, endobronchial ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound with FNA of mediastinal lymph nodes. Tissue from biopsy of lymph nodes is subjected to both flow cytometry to rule out cancer and special stains (acid fast bacilli stain and Gömöri methenamine silver stain) to rule out microorganisms and fungi. Angiotensin-converting enzyme blood levels are used in diagnosis and monitoring of sarcoidosis.[14]

Investigations

Because of wide range of possible manifestations the investigations to confirm diagnosis may involve many organs and methods depending on initial presentation.

Very often Sarcoidosis presents as a restrictive disease of the lungs, causing a decrease in lung volume and decreased compliance (the ability to stretch) - hence chest X-ray and other methods are used to assess the severity or rule out pulmonary disease.

The disease typically limits the amount of air drawn into the lungs, but produces higher than normal expiratory flow ratios. The vital capacity (full breath in, to full breath out) is decreased, and most of this air can be blown out in the first second. This means the FEV1/FVC ratio is increased from the normal of about 80%, to 90%. Obstructive lung changes, causing a decrease in the amount of air that can be exhaled, may occur when enlarged lymph nodes in the chest compress airways or when internal inflammation or nodules impede airflow.

Chest X-ray changes are divided into four stages

- Stage 1 bihilar lymphadenopathy

- Stage 2 bihilar lymphadenopathy and reticulonodular infiltrates

- Stage 3 bilateral pulmonary infiltrates

- Stage 4 fibrocystic sarcoidosis typically with upward hilar retraction, cystic & bullous changes

Investigations to asses involvement of other organs frequently involve electrocardiogram, ocular examination by an ophthalmologist, liver function tests, renal function tests, serum calcium and 24-hour urine calcium.

In female patients sarcoidosis is significantly associated with hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism and other thyroid diseases, hence close surveillance of thyroid function is recommended [15]

Causes and pathophysiology

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is not known. The current working hypothesis is that in genetically susceptible individuals sarcoidosis is caused through alteration in immune response after exposure to an environmental, occupational, or infectious agent.[16]

Dysregulation of the immune system

Granulomatous inflammation is characterized primarily by accumulation of monocytes, macrophages and activated T-lymphocytes, with increased production of key inflammatory mediators, TNF-alpha, INF-gamma, IL-2 and IL-12, characteristic of a Th1-polarized response (T-helper lymphocyte-1 response). Sarcoidosis has paradoxical effects on inflammatory processes; it is characterized by increased macrophage and CD4 helper T-cell activation resulting in accelerated inflammation, however, immune response to antigen challenges such as tuberculin is suppressed. This paradoxic state of simultaneous hyper- and hypo- activity is suggestive of a state of anergy. The anergy may also be responsible for the increased risk of infections and cancer. It appears that regulatory T-lymphocytes in the periphery of sarcoid granulomas suppress IL-2 secretion which is hypothesized to cause the state of anergy by preventing antigen-specific memory responses.[17]

While it is widely believed that TNF-alpha plays an important role in the formation of granulomas, it was observed that sarcoidosis can be triggered by treatment with the TNF-alpha antagonist etanercept.[18][19]

Genetic associations

Investigations of genetic susceptibility yielded many candidate genes but only few were confirmed by further investigations and no reliable genetic markers are known. Currently most interesting candidate gene is BTNL2, several HLA-DR risk alleles are also investigated.[20] In persistent sarcoidosis the HLA haplotype HLA-B7-DR15 are either cooperating in disease or another gene between these two loci is associated. In non-persistent disease there is a strong genetic association with HLA DR3-DQ2.[21] Siblings have only a modestly increased risk (hazard ratio 5-6) to develop the disease, indicating that genetic susceptibility plays only a small role. The alternate hypothesis that family members share similar exposures to environmental pathogens is quite plausible to explain the apparent hereditary factor.

Infectious agents

Several infectious agents appear to be significantly associated with sarcoidosis but none of the known associations is specific enough to suggest a direct causative role. Propionibacterium acnes can be found in bronchoalveolar lavage of approximately 70% patients and is associated with disease activity, however it can be also found in 23% of controls.[22][23] A recent meta-analysis investigating the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis found it was present in 26.4% of cases, however the meta-analysis also detected a possible publication bias, so the results need further confirmation.[24][25]

There have also been reports of transmission of sarcoidosis via organ transplants.[26]

Vitamin D dysregulation

Sarcoidosis frequently causes a dysregulation of vitamin D production with an increase in extrarenal (outside the kidney) production.[27] Specifically, macrophages inside the granulomas convert vitamin D to its active form, resulting in elevated levels of the hormone 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and symptoms of hypervitaminosis D that may include fatigue, lack of strength or energy, irritability, metallic taste, temporary memory loss or cognitive problems. Physiological compensatory responses (e.g., suppression of the parathyroid hormone levels) may mean the patient does not develop frank hypercalcemia. This condition may be aggravated by high levels of estradiol and prolactin such as in pregnancy, leading to hypercalciuria and/or compensatory hypoparathyroidism.[28] High levels of Vitamin D are also implicated in immune-system dysfunctions which tie into the sarcoid condition.

The connection between Vitamin D dysregulation, its effects on immune function, and how the combined effect might mediate sarcoidosis, is currently being explored by Dr. Trevor Marshall. The theory which Dr. Marshall is currently researching via a protocol (the Marshall Protocol) under FDA oversight, asserts that L-form or cell wall deficient bacteria infect the body, and evade the immune system by inducing or enhancing this Vitamin D disregulation, which in turn suppresses the body's immune response to said bacterial infection. Dr. Marshall's research is highly controversial, and the Marshall Protocol's suggestion that people should avoid all sources of vitamin D contradicts a vast body of medical knowledge concerning the benefits of vitamin D. No research about the efficacy of the Marshall Protocol has been published in a medical journal. Marshall is not a medical doctor; his doctorate is in electrical engineering.[29]

Hyperprolactinemia

Prolactin is frequently increased in sarcoidosis, between 3–32% cases have hyperprolactinemia,[30] this frequently leads to amenorrhea, galactorrhea or nonpuerperal mastitis in women. Prolactin also has a broad spectrum of effects on the immune system and increased prolactin levels are associated with disease activity or may exacerbate symptoms in many autoimmune diseases and treatment with prolactin lowering medication has been shown effective in some cases.[31] However it is unknown if this relation holds in sarcoidosis and the gender predilection in sarcoidosis is less pronounced than in some other autoimmune diseases where such relation has been established. In pregnancy, the effects of prolactin and estrogen counteract each other to some degree, with a slight trend to improve pulmonary manifestations of sarcoidosis while lupus, uveitis and arthralgia might slightly worsen.[28] Lupus, uveitis and arthralgia are known to be in some cases associated with increased prolactin levels and respond to bromocriptin treatment but so far this has not been investigated specifically for sarcoidosis. The reasons for increased prolactin levels in sarcoidosis are uncertain. It has been observed that prolactin is produced by T-lymphocytes in some autoimmune disorders in amounts high enough to affect the feedback by the hypothalamic dopaminergic system.[32]

The extrapituitary prolactin is believed to play a role as a cytokine like proinflammatory factor. Prolactin antibodies are believed to play a role in hyperprolactinemia in other autoimmune disorders and high prevalence endocrine autoimmunity has been observed in patients with sarcoidosis.[33] It may also be a consequence of renal disease or treatment with steroids. Neurosarcoidosis may occasionally cause hypopituiarism but has not been reported to cause hyperprolactinemia.

Thyroid disease

In women, a substantial association of thyroid disease and sarcoidosis has been reported. The association is less marked but still significant for male patients. Female patients have a significantly elevated risk for hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism and thyroid autoimmunity and it appears that autoimmunity is very important in the pathogenesis of thyroid disease in this population. Thyroid granulomatosis on the other hand is uncommon.[15]

Hypersensitivity/autoimmune

Association of autoimmune disorders has been frequently observed. The exact mechanism of this relation is not known but some evidence supports the hypothesis that this is a consequence of Th1 lymphokine prevalence.[34][15]

Sarcoidosis has been associated with celiac disease. Celiac disease is a condition in which there is a chronic reaction to certain protein chains, commonly referred to as glutens, found in some cereal grains. This reaction causes destruction of the villi in the small intestine, with resulting malabsorption of nutrients.

An association with type IV hypersensitivity has been described.[35] Tests of delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity have been used to measure progression.[36]

Other

While disputed, some cases have been associated with inhalation of the dust from the collapse of the World Trade Center after the September 11, 2001 attacks.[37] See Health effects arising from the September 11, 2001 attacks for more information.

Pregnancy

Sarcoidosis generally does not prevent successful pregnancy and delivery, the endogenous estrogen in pregnancy may even have a slightly beneficial immunomodulatory effect. In most cases the course of sarcoidosis is unaffected by pregnancy, there is improvement in a few cases and worsening of symptoms in very few cases.[28]

Treatment

Between 30 and 70% of patients do not require therapy.[3] Corticosteroids, most commonly prednisone, have been the standard treatment for many years. In some patients, this treatment can slow or reverse the course of the disease, but other patients do not respond to steroid therapy. The use of corticosteroids in mild disease is controversial because in many cases the disease remits spontaneously.[38] Additionally, corticosteroids have many recognized dose- and duration-related side effects (which can be reduced through the use of alternate-day dosing for those on chronic prednisone therapy),[39] and their use is generally limited to severe, progressive, or organ-threatening disease. The influence of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants on the natural history is unclear.

Severe symptoms are generally treated with steroids, and steroid-sparing agents such as azathioprine and methotrexate are often used. Rarely, cyclophosphamide has also been used. As the granulomas are caused by collections of immune system cells, particularly T cells, there has been some early indications of success using immunosuppressants, interleukin-2 inhibitors or anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment (such as infliximab). Unfortunately, none of these has provided reliable treatment, and there can be significant side effects such as an increased risk of reactivating latent tuberculosis. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha treatment with etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis has been observed to cause sarcoidosis.[18]

The connection between vitamin D dysregulation and the emergence of sarcoidosis is being explored under the Marshall Protocol, which asserts that cell-wall deficient bacteria infect the body and evade immune surveillance by promoting such dysregulation, which in turn suppresses the body's immune response.

Because sarcoidosis can affect multiple organ systems, follow-up on a patient with sarcoidosis should always include an electrocardiogram, ocular examination by an ophthalmologist, liver function tests, serum calcium and 24-hour urine calcium. In female patients sarcoidosis is significantly associated with hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism and other thyroid diseases, hence close surveillance of thyroid function is recommended.[15]

Prognosis

The disease can remit spontaneously or become chronic, with exacerbations and remissions. In some patients, it can progress to pulmonary fibrosis and death. Approximately half of the cases resolve or can be cured within 12–36 months and most within 5 years. Some cases persist several decades.[3] Where the heart is involved, the prognosis is poor.[40] Patients with sarcoidosis appear to be at significantly increased risk for cancer, in particular lung cancer, malignant lymphomas,[41] and cancer in other organs known to be affected in sarcoidosis.[42] In sarcoidosis-lymphoma syndrome, sarcoidosis is followed by the development of a lymphoproliferative disorder such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[43] This may be attributed to the underlying immunological abnormalities that occur during the sarcoidosis disease process.[44] Sarcoidosis can also follow cancer [45] or occur concurrently with cancer.[46]

See also

- Garland's triad

- Kveim test

- HLA-A69

- Bernie Mac (late actor-comedian / a sarcoidosis patient)

- Cicatricial alopecia

References

- ^ "sarcoidosis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b Syed, J.; Myers, R. (2004). "Sarcoid heart disease". Can J Cardiol. 20 (1): 89–93. PMID 14968147.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D (2007). "Sarcoidosis". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2: 46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46. PMC 2169207. PMID 18021432.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Henke, CE.; Henke, G.; Elveback, LR.; Beard, CM.; Ballard, DJ.; Kurland, LT. (1986). "The epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Rochester, Minnesota: a population-based study of incidence and survival". Am J Epidemiol. 123 (5): 840–5. PMID 3962966.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "American Thoracic Society: Statement on Sarcoidosis." Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:736-755.

- ^ a b James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Andrews" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: DCI Home: Lung Diseases: Sarcoidosis: Signs & Symptoms Retrieved on May 9, 2009.

- ^ Tolaney SM, Colson YL, Gill RR, Schulte S, Duggan MM, Shulman LN, Winer EP. Sarcoidosis mimicking metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007 Oct;7(10):804-10. PubMed PMID: 18021484.

- ^ "Sarcoidosis and the Heart". Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research. Accessed 2 Dec 2007. [1]

- ^ Anna M.McDivit and Arman T. Askari,"A Middle-aged Man with Progressive Fatigue,"Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2009; 76(10):564-574 Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3949/ccjm.76a.08114, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3949/ccjm.76a.08114instead. - ^ Heart. 2006 February; 92(2): 282–288. Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1136/hrt.2005.080481, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1136/hrt.2005.080481instead. - ^ Forensic Science International, Volume 89, Issue 3, Pages 145-153

- ^ Rajasenan, V.; Cooper, ES. (1969). "Myocardial sarcoidosis, bouts of ventricular tachycardia, psychiatric manifestations and sudden death. A case report". J Natl Med Assoc. 61 (4): 306–9. PMID 5796402.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.labtestsonline.org/understanding/analytes/ace/test.html

- ^ a b c d .Antonelli A, Fazzi P, Fallahi P, Ferrari SM, Ferrannini E (2006). "Prevalence of hypothyroidism and Graves disease in sarcoidosis". Chest. 130 (2): 526–32. doi:10.1378/chest.130.2.526. PMID 16899854.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "Antonelli_2006_16899854" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Rossman MD, Kreider ME (2007). "Lesson learned from ACCESS (A Case Controlled Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis)". Proc Am Thorac Soc. 4 (5): 453–6. doi:10.1513/pats.200607-138MS. PMID 17684288.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kettritz R, Goebel U, Fiebeler A, Schneider W, Luft F (2006). "The protean face of sarcoidosis revisited". Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 21 (10): 2690–4. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfl369. PMID 16861724.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Verschueren K, Van Essche E, Verschueren P, Taelman V, Westhovens R (2007). "Development of sarcoidosis in etanercept-treated rheumatoid arthritis patients". Clin. Rheumatol. 26 (11): 1969–71. doi:10.1007/s10067-007-0594-1. PMID 17340045.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stokes MB, Foster K, Markowitz GS (2005). "Development of glomerulonephritis during anti-TNF-alpha therapy for rheumatoid arthritis". Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 20 (7): 1400–6. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh832. PMID 15840673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Iannuzzi MC (2007). "Advances in the genetics of sarcoidosis". Proc Am Thorac Soc. 4 (5): 457–60. doi:10.1513/pats.200606-136MS. PMID 17684289.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Grunewald J, Eklund A, Olerup O (2004). "Human leukocyte antigen class I alleles and the disease course in sarcoidosis patients". Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169 (6): 696–702. doi:10.1164/rccm.200303-459OC. PMID 14656748.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hiramatsu J, Kataoka M, Nakata Y (2003). "Propionibacterium acnes DNA detected in bronchoalveolar lavage cells from patients with sarcoidosis". Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 20 (3): 197–203. PMID 14620162.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Inoue Y, Suga M (2008). "[Granulomatous diseases and pathogenic microorganism]". Kekkaku (in Japanese). 83 (2): 115–30. PMID 18326339.

- ^ Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK (2007). "Molecular evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis". Eur. Respir. J. 30 (3): 508–16. doi:10.1183/09031936.00002607. PMID 17537780.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Almenoff PL, Johnson A, Lesser M, Mattman LH. Growth of acid fast L forms from the blood of patients with sarcoidosis. Thorax 1996;51:530-3. PMID 8711683.

- ^ Padilla ML, Schilero GJ, Teirstein AS. Donor-acquired sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2002;19:18-24. PMID 12002380.

- ^ Barbour GL, Coburn JW, Slatopolsky E, Norman AW, Horst RL. Hypercalcemia in an anephric patient with sarcoidosis: evidence for extrarenal generation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. N Engl J Med 1981;305:440-3. PMID 6894783.

- ^ a b c Subramanian P, Chinthalapalli H, Krishnan M (2004). "Pregnancy and sarcoidosis: an insight into the pathogenesis of hypercalciuria". Chest. 126 (3): 995–8. doi:10.1378/chest.126.3.995. PMID 15364785.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ University of Melbourne seminar (2006)."Molecular Mechanisms Driving the Current Epidemic of Chronic Disease"

- ^ Porter N, Beynon HL, Randeva HS (2003). "Endocrine and reproductive manifestations of sarcoidosis". QJM. 96 (8): 553–61. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg103. PMID 12897340.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yu-Lee LY (2002). "Prolactin modulation of immune and inflammatory responses". Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 57: 435–55. doi:10.1210/rp.57.1.435. PMID 12017556.

- ^ Méndez I, Alcocer-Varela J, Parra A (2004). "Neuroendocrine dopaminergic regulation of prolactin release in systemic lupus erythematosus: a possible role of lymphocyte-derived prolactin". Lupus. 13 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1191/0961203304lu487oa. PMID 14870917.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Papadopoulos KI, Hörnblad Y, Liljebladh H, Hallengren B (1996). "High frequency of endocrine autoimmunity in patients with sarcoidosis". Eur. J. Endocrinol. 134 (3): 331–6. doi:10.1530/eje.0.1340331. PMID 8616531.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Romagnani S (1997). "The Th1/Th2 paradigm". Immunol. Today. 18 (6): 263–6. doi:10.1016/S0167-5699(97)80019-9. PMID 9190109.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "eMedicine - Hypersensitivity Reactions, Delayed : Article by Walter Duane Hinshaw". Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Morell F, Levy G, Orriols R, Ferrer J, De Gracia J, Sampol G (2002). "Delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity tests and lymphopenia as activity markers in sarcoidosis". Chest. 121 (4): 1239–44. doi:10.1378/chest.121.4.1239. PMID 11948059.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ New York Times article, May 24, 2007

- ^ White, E.S.; Lynch Jp, 3rd (2007). "Current and emerging strategies for the management of sarcoidosis". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (9): 1293–1311. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.9.1293. PMID 17563264.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dosing Considerations"

- ^ J.Syed and R. Myers, "Sarcoid Heart Disease," Can J Cardiol. 2004 Jan;20(1):89-93.

- ^ Karakantza, M.; Matutes, E.; MacLennan, K.; O'Connor, NT.; Srivastava, PC.; Catovsky, D. (1996). "Association between sarcoidosis and lymphoma revisited". J Clin Pathol. 49 (3): 208–12. PMID 8675730.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ J. Askling; et al., "Increased Risk for Cancer Following Sarcoidosis," Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., Volume 160, Number 5, November 1999, 1668-1672

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s00277-001-0415-6, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s00277-001-0415-6instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s12032-007-0026-8, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s12032-007-0026-8instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.089, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1200/JCO.2005.02.089instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1378, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1378instead.

Additional images

-

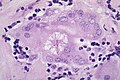

Sarcoidosis in a lymph node.

-

Asteroid Body in sarcoidosis.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- "Kveim test". GPnotebook.

- Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research

- WASOG World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders

- Dorothy P. and Richard P. Simmons Center for Interstitial Lung Diseases at the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Images

- Pathology Images of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases Yale Rosen, M.D.

- Microscopy of granulomas in sarcoidosis

- MedPix Pulmonary Sarcoid- Bilateral Hilar Adenopathy