Gospel of Matthew: Difference between revisions

→The Four Source Hypothesis: wikilinks |

|||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

[[Image:Streeter's the Four Document Hypothesis.PNG|thumb|360px|The Streeter's Four Document Hypothesis]] |

[[Image:Streeter's the Four Document Hypothesis.PNG|thumb|360px|The Streeter's Four Document Hypothesis]] |

||

{{main|Four Document Hypothesis}} |

|||

| ⚫ | In ''The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins'' (1924), [[Burnett Hillman Streeter]] argued that a third source, referred to as ''M'' and also hypothetical<ref>http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Ch9.htm</ref>, lies behind the material in Matthew that has no parallel in Mark or Luke.<ref>Streeter, Burnett H. ''[http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Contents.htm The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins Treating the Manuscript Tradition, Sources, Authorship, & Dates]''. London: MacMillian and Co., Ltd., 1924.</ref> This Four Source Hypothesis posits that there were at '''least''' four sources to the ''Gospel of Matthew'' and the ''Gospel of Luke'': the ''Gospel of Mark'', and three lost sources: [[Q document|Q]], M, and L. |

||

| ⚫ | In ''The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins'' (1924), [[Burnett Hillman Streeter]] argued that a third source, referred to as ''M'' and also hypothetical<ref>http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Ch9.htm</ref>, lies behind the material in Matthew that has no parallel in Mark or Luke.<ref>Streeter, Burnett H. ''[http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Contents.htm The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins Treating the Manuscript Tradition, Sources, Authorship, & Dates]''. London: MacMillian and Co., Ltd., 1924.</ref> This ''Four Source Hypothesis'' posits that there were at '''least''' four sources to the ''Gospel of Matthew'' and the ''Gospel of Luke'': the ''Gospel of Mark'', and three lost sources: [[Q document|Q]], M, and L. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | According to this view, the first Gospel is a combination of the traditions of [[Early centers of Christianity#Jerusalem|Jerusalem]], [[Early centers of Christianity#Antioch|Antioch]], and [[Early centers of Christianity#Rome|Rome]], while the third Gospel represents [[Early centers of Christianity##Caesarea|Caesarea]], Antioch, and Rome. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, there were various challenges and refinements of Streeter's hypothesis. For example, in his 1953 book ''The Gospel Before Mark'', Pierson Parker posited an early version of Matthew (Aram. M or proto-Matthew) as the primary source.<ref>Pierson Parker. ''The Gospel Before Mark''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.</ref> |

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, there were various challenges and refinements of Streeter's hypothesis. For example, in his 1953 book ''The Gospel Before Mark'', Pierson Parker posited an early version of Matthew (Aram. M or proto-Matthew) as the primary source.<ref>Pierson Parker. ''The Gospel Before Mark''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.</ref> |

||

| Line 44: | Line 46: | ||

Parker argued that it was not possible to separate Streeter's "M" material from the material in Matthew parallel to Mark.<ref>The Synoptic Problem: a Critical Analysis, by William R. Farmer. New York: Macmillan, 1981 Page 196</ref><ref> [http://books.google.ca/books?id=qh7b4o6JQpIC&pg=PA152&lpg=PA152&dq=Aramaic+matthew++%22The+special+sources+may+be+roughly+equated+with+Streeter's+M+and+L%22&source=bl&ots=CAsNiP8nVQ&sig=immjJFyZRoEjVtx73DWH0a5HYYk&hl=en&ei=AUZBSvO9LcLllAeclqn8CA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1 Everett Falconer Harrison, ''Introduction to the New Testament'', Wm. Eerdmans 1971, p. 152. ] |

Parker argued that it was not possible to separate Streeter's "M" material from the material in Matthew parallel to Mark.<ref>The Synoptic Problem: a Critical Analysis, by William R. Farmer. New York: Macmillan, 1981 Page 196</ref><ref> [http://books.google.ca/books?id=qh7b4o6JQpIC&pg=PA152&lpg=PA152&dq=Aramaic+matthew++%22The+special+sources+may+be+roughly+equated+with+Streeter's+M+and+L%22&source=bl&ots=CAsNiP8nVQ&sig=immjJFyZRoEjVtx73DWH0a5HYYk&hl=en&ei=AUZBSvO9LcLllAeclqn8CA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1 Everett Falconer Harrison, ''Introduction to the New Testament'', Wm. Eerdmans 1971, p. 152. ] |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

The consensus view of the contemporary New Testament scholars is that the ''Gospel of Matthew'' was originally composed in [[ |

The consensus view of the contemporary New Testament scholars is that the ''Gospel of Matthew'' was originally composed in [[Koine Greek|Greek]] not [[Hebrew]] or [[Aramaic]]<ref name="Erhman43"/>, and that the apostle Matthew did not write the Gospel that bears his name.<ref name="Brown 210"/> |

||

===Church Fathers=== |

===Church Fathers=== |

||

Revision as of 17:48, 18 March 2010

| Part of a series on |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

The Gospel According to Matthew (Template:Lang-el, to euangelion kata Matthaion) commonly shortened to the Gospel of Matthew, is one of the four Canonical gospels and is the first book of the New Testament. This synoptic gospel is an account of the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth. It details his story from his genealogy to his Great Commission.[1][2]

The Gospel of Matthew is closely aligned with first-century Judaism, and stresses how Jesus fulfilled Jewish prophecies.[3] Certain details of Jesus' life, of his infancy in particular, are only related by Matthew. His is the only gospel to mention the Church or ecclesia.[3] Matthew also emphasizes obedience to and preservation of biblical law.[4] Since this gospel has rhythmical and often poetical prose,[5] it is well suited for public reading, making it a popular liturgical choice.[6]

Most scholars believe the Gospel of Matthew was composed in the latter part of the first century by a Jewish Christian.[7] Early Christian writings state that Matthew the Apostle wrote the Hebrew Gospel.[8][9][10] However most scholars today believe that "canonical Matt was originally written in Greek by a non eyewitness whose name is unknown to us and who depended on sources like Mark and Q."[11][12][13] although others disagree variously on those points.[13][14]

The Gospel of Matthew can be broken down into into five distinct sections: the Sermon on the Mount (ch 5-7), the Mission Instructions to the Twelve (ch 10), the Three Parables (ch 13), Instructions for the Community (ch 18), and the Olivet Discourse (ch 24-25). Some believe this was to reflect the Pentateuch. [15] [16]

Composition

Traditionally, (see Augustinian hypothesis), Matthew was seen as the first Gospel written, that Luke then expanded on Matthew, and that Mark is the conflation of both Matthew and Luke.[13][14] It was believed that the Gospel of Matthew was composed by Matthew, a disciple of Jesus.[17]

However, 18th Century scholars increasingly questioned the traditional view of composition. Today, most critical scholarship agrees that Matthew did not write the Gospel which bears his name, [18] preferring instead to describe the author as an anonymous Jewish Christian, writing towards the end of the first century. They also believe that the Gospel was originally composed in Greek (see Greek primacy) rather than being a translation from an Aramaic Matthew or the Hebrew Gospel.[19]

Synoptic Gospels

The Gospels of Mark, Matthew and Luke (known as the Synoptic Gospels) include many of the same episodes, often in the same sequence, and sometimes even in the same wording. The relationship of Gospel of Matthew to the Gospels of Mark and Luke is an open question known as the synoptic problem.

The Gospel of Matthew contains around 612 verses of the 662 verses of the Gospel of Mark, and mostly in exactly the same order.[20] Matthew however quite frequently removes or modifies from Mark redundant phrases or unusual words and modifies the passages in Mark's gospel that might put Jesus in a negative light (e.g. removing the highly critical comment that Jesus "is out of his mind" in Mark 3:21, removing "do you not care" from Mark 4:38 etc) [21]

Although the author of Matthew wrote according to his own plans and aims and from his own point of view, the great amount of overlap in sentence structure and word choice indicates that Matthew copied from other Gospel writers, or they copied from each other, or they all copied from another common source. This synoptic problem increasingly caused 18th Century scholars to question the traditional view of composition.[12][13]

One solution to the Synoptic problem is the Farrer hypothesis, which theorizes that Matthew borrowed material only from Mark, and that Luke wrote last, using both earlier Synoptics.

The most popular view in modern scholarship is the two-source hypothesis, which speculates that Matthew borrowed from both Mark and a hypothetical sayings collection, called Q (for the German Quelle, meaning "source"). For most scholars, the Q collection accounts for what Matthew and Luke share — sometimes in exactly the same words — but are not found in Mark. Examples of such material are the Devil's three temptations of Jesus, the Beatitudes, the Lord's Prayer and many individual sayings.[13][14][22]

A minority of scholars continued to defend the tradition, which asserts Matthean priority, with Mark borrowing from Matthew (see: Augustinian hypothesis and Griesbach hypothesis). Then in 1911, the Pontifical Biblical Commission[23] asserted that Matthew was the first gospel written, that it was written by the evangelist Matthew, and that it was written in Aramaic.[24]

The Four Source Hypothesis

In The Four Gospels: A Study of Origins (1924), Burnett Hillman Streeter argued that a third source, referred to as M and also hypothetical[25], lies behind the material in Matthew that has no parallel in Mark or Luke.[26] This Four Source Hypothesis posits that there were at least four sources to the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke: the Gospel of Mark, and three lost sources: Q, M, and L.

According to this view, the first Gospel is a combination of the traditions of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Rome, while the third Gospel represents Caesarea, Antioch, and Rome.

The fact that the Antiochene and Roman sources were reproduced by both Evangelists Matthew and Luke was due to the importance of those Churches. Streeter thought there is no evidence that the other sources are less authentic.

Throughout the remainder of the 20th century, there were various challenges and refinements of Streeter's hypothesis. For example, in his 1953 book The Gospel Before Mark, Pierson Parker posited an early version of Matthew (Aram. M or proto-Matthew) as the primary source.[27]

Parker argued that it was not possible to separate Streeter's "M" material from the material in Matthew parallel to Mark.[28][29] The consensus view of the contemporary New Testament scholars is that the Gospel of Matthew was originally composed in Greek not Hebrew or Aramaic[19], and that the apostle Matthew did not write the Gospel that bears his name.[11]

Church Fathers

Matthean authenticity has been seriously challenged by many present day scholars. It was also an issue for the Early Church. It was believed by Jerome [30] that the Gospel of the Hebrews was the true Gospel of Matthew (or Matthaei Authenticum).[31] [4] Also, Epiphanius [32] in his Panarion, in which he discusses the gospel used by the followers of Cerinthus, Merinthus and the Ebionites, writes: "They too accept Matthew's gospel and like the followers of Cerinthus and Merinthus, they use it alone. They call it the Gospel of the Hebrews, for in truth, Matthew alone of the New Covenant writers expounded and declared the gospel in Hebrew using Hebrew script." [33]

The first reference to the Hebrew text written by the disciple Matthew comes from Papias [34] Papias starts by discussing the origin of the Gospel of Mark, and then further remarks that "Matthew composed the logia in the Hebrew tongue and each one interpreted them as he was able". According to Ehrman this is not a reference to the canonical gospel, since the canonical Gospel of Matthew was originally written in Greek and not Hebrew.[19] [35][36][37]

Apart from Papias' comment, we do not hear about the author of the Gospel until Irenaeus [38] around 185 who remarks that Matthew also issued a written Gospel of the Hebrews in their own language while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome and laying the foundations of the Church.[10][39]

Pantaenus, Origen and other Early Church Fathers also believed Matthew wrote the Gospel of the Hebrews.[19][40][41] Finally, the Church Fathers never asserted that Matthew wrote the Greek Gospel found in the Bible.[42]

Contemporary scholarship

A study of the external evidence, shows that there existed among the Nazarene and Ebionite Communities, a gospel commonly referred to as the Gospel of the Hebrews. It was written in Aramaic and its authorship was attributed to St. Matthew. Indeed, the Fathers of the Church, while the Gospel of the Hebrews was still being circulated and read, always referred to it with respect. The Early Church Fathers (Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, Irenaeus Origen, Jerome etc) all made reference to this gospel of Matthew.

Some modern scholars believe that the Apostle Matthew wrote an eye witness account in Hebrew of the life of Jesus long before any of the Canonical Gospels and that this Gospel of the Hebrews was considered authentic, held in very high regard by Early Church leaders and was the basis for future gospels including the Gospel of Matthew found in the Bible.[43] [44] [45] [46]

Matthew the Evangelist

Matthew was a Galilean and the son of Alpheus [47] He collected taxes from the Hebrew people for Herod Antipas. His Tax Office was located in Capharnaum where he was despised and considered an outcast. However, as a tax collector he would have been literate.[48] [49][50] It was in this setting, that Jesus called Matthew to be one of the Twelve Disciples. and after his call, Matthew invited the Lord home for a feast.[51][52][53][54][55]

As a disciple, Matthew followed Christ, and was one of the witnesses of the Resurrection and the Ascension. Matthew along with Mary, James the brother of Jesus and other close followers of the Lord, withdrew to the Upper Chamber, in Jerusalem.[56][57][58][59] At about this time James succeeded his brother Jesus of Nazareth as the leader of this small Jewish sect.[60]

They remained in and about Jerusalem and proclaimed that Jesus son of Joseph was the promised Messiah. These early Jewish Christians were thought to have been called Nazerenes.[61][62] It is near certain that Matthew belonged to this sect, as both the New Testament and the early Talmud affirm this to be true.[63]

Matthew is said to have died a natural death either in Ethiopia or in Macedonia. However, the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church say he died a martyr.[64][65]

Matthew was also said to have written the very first Gospel [66][67][68] in Hebrew near Jerusalem for Hebrew Christians and it was translated into Greek, but the Greek copy was lost. The Hebrew original was kept at the Library of Caesarea. The Nazarene Community transcribed a copy for Jerome [5] which he used in his work.[69] Matthew's Gospel was called the Gospel according to the Hebrews [6] or sometimes the Gospel of the Apostles [70][71] and it was once believed that it was the original to the Greek Matthew found in the Bible, but this has been largely disproved by modern Biblical Scholars.[72]

Date of gospel

The date of this gospel is still a matter of debate among Biblical scholars. Some believe it was composed between the years 70 and 100, but others claim that there is absolutley no way that it could have been written in this time given the average lifespan of most people at that time. [73][74][75][76] The writings of Ignatius show "a strong case ... for [his] knowledge of four Pauline epistles and the Gospel of Matthew"[77], which gives a terminus ad quem of c. 110. The author of the Didache (c 100) probably knew it as well.[6] Some scholars see the prophecies of the destruction of Jerusalem (e.g. in Matthew 22:7) as suggesting a date of authorship after the siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD:[78] However, John A. T. Robinson argues that the lack of a passage indicating the fulfilment of the prophecy suggest a date before that[79]. Matthew does not mention the death of James in 62 AD. It also lacks any narrative on the persecutions of the early Christians by Nero.

This view has been challenged by two scholars almost a century apart, The Reverend C. B. Huleatt and Carsten Peter Thiede. In December 1994, Carsten Peter Thiede redated the Magdalen papyrus, which bears a fragment from the Gospel of Matthew, to the late 1st century on palaeographical grounds, and thus contended that the Gospel of Matthew was written by an eye-witness.[80][81][82][83][84][85][86] [7] [8][9] [10] [11]

Characteristics

W. R. F. Browning notes that Matthew avoids using the holy word God in the expression "Kingdom of God". Instead he prefers the term "Kingdom of Heaven". This was due to Matthew's rabbinical background, which reflects the Jewish tradition of not speaking the name of God.

Matthew also divides his work into great blocks each ending with the phrase: "When Jesus had finished these sayings ..." This narrative framework echoes that of the Hexateuch: "the birth narratives/Genesis; the baptism in the Jordon and Jesus' temptations/Exodus; healing of a leper and an untouchable woman/Leviticus; callings of disciples/Numbers; the Passion and Death of Jesus/Deuteronomy; the Resurrection/Joshua (the entry into promised land)".[87] Graham N. Stanton discounts the suggestion that the "five" discourses are an imitation of the first five books of the Old Testament arguing that many Jewish and Greco-Roman writings have five divisions or sections.[88]

Overview

Template:Content of Matthew For convenience, the Gospel of Matthew can be divided into its four structurally distinct sections: Two introductory sections; the main section, which can be further broken into five sections, each with a narrative component followed by a long discourse of Jesus; and finally, the Passion and Resurrection section.

- Containing the genealogy, the birth, and the infancy of Jesus (Matthew 1; Matthew 2).

- The discourses and actions of John the Baptist preparatory to Christ's public ministry (Matthew 3; Matthew 4:11).

- The discourses (and actions) of Christ (4:12–26:1).

- The Sermon on the Mount, concerning morality (Ch. 5–7)

- The Missionary Discourse, concerning the mission Jesus gave his Twelve Apostles. (10–11:1)

- The Parable Discourse, stories that teach about the Kingdom of Heaven (13).

- The "Church Order" Discourse, concerning relationships among disciples (18–19:1).

- The Olivet Discourse on the Last Things: his Second Coming, Judgement of the Nations, and the end of the age (24–25).

- The sufferings, death and Resurrection of Jesus, the Great Commission (26-28).

Genealogy and Infancy narrative

Matthew (like Luke) provides a genealogy and an infancy narrative of Jesus. Although the two accounts differ, both agree on Jesus being both Son of David, and Son of God, and on his virgin birth, and according to Howard W. Clarke, that Jesus' status as the long-awaited Messiah and as the Son of God was assured before his birth rather than being conferred later in his ministry or acquired after his death.[89]

Genealogy

After giving a genealogy from Abraham to Jesus, Matthew gives the number of generations from Abraham to David, from David to the deportation to Babylon, and from the deportation to Jesus as fourteen each. (In fact, the total number of men in the list, including both Abraham and Jesus, is only 41 in the Greek texts whereas the Syriac Curetonian, Syriac Sinaitic, and Dutillet Matthew have 42).[90] Matthew traces the genealogy of Jesus through Joseph, not Mary. Matthew puts Joseph a descendant of David's son Solomon while in Luke he is descended from another son of David, Nathan.[91] After David, the lists coincide again at Shealtiel and Zerubbabel (founder of the second temple) but then again part company until they reach Joseph through his father (Jacob according to Matthew; Heli in Luke).[91]

These and other differences between Matthew's and Luke's genealogy have presented a problem for both ancient and modern readers of the Gospels. An early explanation given by Julius Africanus, was that supposedly on the authority of Jesus family, involving levirate marriage, Joseph's official father was not his biological father (see Genealogy of Jesus). Some have suggested that Matthew wants to underscore the birth of a messianic child of royal lineage (mentioning Solomon) whereas Luke's genealogy is priestly (mentioning Levi, but note that the Levi in question is not the ancestor of the Levites but rather the grandfather of Heli).[92][93] According to Scott Gregory Brown, the reason for the difference between the two genealogies is that it was not included in the written accounts that the writers of the two Gospels shared (i.e. Gospel of Mark and Q).[94] Two other common reasons are (1) Luke presents Mary’s genealogy, while Matthew relates Joseph’s; (2) Luke has Jesus’ actual human ancestry through Joseph, while Matthew gives his legal ancestry by which he was the legitimate successor to the throne of David.[95] According to Howard W. Clarke, the two accounts cannot be harmonized and today the genealogy accounts are generally taken to be "theological" constructs.

Taken this way, writes Stanton, the genealogy foreshadows acceptance of Gentiles into the Kingdom of God: in reference to Jesus as "the Son of Abraham", the author has in mind the promise given to Abraham in Gen 22:18. Matthew holds that due to Israel's failure to produce the "fruits of the kingdom" and her rejection of Jesus, God's kingdom is now taken away from Israel and given to Gentiles. Another foreshadowing of the acceptance of Gentiles is the inclusion of four women in the genealogy (three of whom were Gentiles), something unexpected to a first century reader. According to Stanton, women are probably representing non-Jews to a first century reader.[96] According to Markus Bockmuehl et al., Matthew is mentioning this to prepare his reader for the apparent scandal surrounding Jesus' birth by emphasizing the point that God's purpose is sometimes worked out in unorthodox and surprising ways.[97]

Infancy narrative

Mary becomes pregnant "of the Holy Spirit", and so Joseph decides to break his relationship with her quietly. He however has a dream with the promise of the birth of Jesus. The gospel proceeds with visit of the Magi who acknowledge the infant Jesus as king. This is followed by Herod's massacre of the innocents and the flight into Egypt, and an eventual journey to Nazareth.[98]

According to Mary Clayton, the chief aim of the infancy narrative is to convince readers of the divine nature of Jesus through his conception through the Holy Spirit and his virgin birth; the visit of Magi and flight into Egypt intended to show that Jesus' kingship is not restricted to Jews but is rather universal.[98]

Baptism and Temptation

John baptizes Jesus, and the Holy Spirit descends upon him. The evangelist addresses the puzzling scene of Jesus, reputedly born sinless, being baptized. He omits reference to baptism being for forgiveness of sins and depicts John emphasizing his inferiority to Jesus. The descent of the Holy Spirit tells the reader that Jesus has become God's anointed (Messiah or Christ).[3]

Jesus prays and meditates in the wilderness for forty days, and then is tempted by the Devil. Jesus refutes the Devil with quotations from Jewish Law.[3]

Sermon on the Mount

Matthew's principal addition to Mark's narrative is five collections of teaching material, and the first is the Sermon on the Mount. Jesus, presented as a greater Moses, completes and transcends Mosaic law. The Beatitudes bless the poor in spirit and the meek. In six expositions or antitheses (depending on how the sermon is interpreted, see Expounding of the Law), Jesus reinterprets the Law. He offers the Lord's prayer as a simple alternative to ostentatious prayer.[3] The Lord's prayer contains parallels to First Chronicles 29:10-18.[99] Critical scholars see the historical Jesus in his startling congratulations to the unfortunate and his call to return violence with forgiveness ("turn the other cheek", see also Evangelical counsels).[100] Matthew's beatitudes differ from those found in Luke.[100] The paradoxical blessings in Luke to the poor and hungry are here blessings to the poor in spirit and those who hunger for justice.[100] In addition, Matthew has more blessings than Luke, the extras apparently derived from Psalms and from numerous precedents for virtues being rewarded.[100]

Instructions to the Twelve Disciples

Matthew names the Twelve Disciples. Jesus sends them to preach to the Jews, perform miracles, and prophesy the imminent coming of the Kingdom.[3] Jesus commands them to travel lightly, without even a staff or sandals. He tells them they will face persecution. Scholars are divided over whether the rules originated with Jesus or with apostolic practice.[100]

Parables on the Kingdom

Jesus tells the parable of the sower, paralleling Mark. Like Mark and Luke, Matthew portrays Jesus as using parables in order to prevent the unworthy from receiving his message. The parables of the wheat and the tares and of the net, unique to Matthew, portray God's sure judgment as indefinitely delayed. The parables of the mustard seed and of the pearl "of very special value" emphasize the secret nature and incomprehensible worth of the Kingdom.[3]

Instructions to the Church

Matthew is the only Gospel to discuss the ecclesia (Greek: assembly), or church. In Matthew, Jesus establishes his church on Peter, giving Peter and the Church the power to bind and loose (or forbid and allow). The instructions for the church emphasize ecclesiastical responsibility and humility. He calls on his disciples to practice forgiveness, but he also gives them the authority to excommunicate the unrepentant.[3] Peter's special commission has been highly influential[6] (see Saint Peter).

Fifth discourse

Jesus heaps the "seven woes" on the scribes and Pharisees. This hostility is thought to represent the attitude of the first-century church.[3]

Signs of the Times

Matthew expands Marks' account of the Parousia, or Second Coming. Matthew mentions such things as false Messiahs, earthquakes, and persecution of his disciples, but states that these are not signs of the end times. After the tribulation, the sun, moon, and stars will fail. The declaration that his generation would not pass away before all the prophecies are fulfilled indicates that the author thought himself to be living in the last days. This discourse might incorporate two different Parousia traditions, one with typical apocalyptic signs and the other emphasizing that the Master will return without warning.[3]

Parables and vision of the Second Coming

The parables of the foolish virgins and of the talents emphasize constant readiness and Jesus' unexpected return. In a prophetic vision, Jesus judges the world. The godly ("sheep") are those who helped those in need, while the wicked ("goats") are those who did not.[3]

Final Days and Resurrection

Matthew generally follows Mark's sequence of events. Jesus triumphantly enters Jerusalem and drives the money changers from the temple. He identifies Judas Iscariot as his traitor. Jesus prays to be spared the coming agony, and a mob takes him by force to the Sanhedrin. To the trial, Matthew adds the detail that Pilate's wife, tormented by a dream, tells him to have nothing to do with "that righteous man", and Pilate washes his hands of him. To Mark's account of Jesus' death, Matthew adds the occurrence of an earthquake, and saints arising from their tombs and appearing to many people in Jerusalem (Matthew 27:51–53). He also provides two stories of the Jewish leaders conspiring to undermine belief in the resurrection (Matthew 28:11–15), and he describes Mark's "young man" at Jesus' tomb as being a radiant angel (Matthew 28:3). Matthew does not relate any of Jesus' post-resurrection appearances to the disciples in Judea, nor his Ascension. He appears to the Eleven in Galilee and commissions them to preach to the world: "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations baptizing them in the name (singular) of the Father of the Son and of the Holy Spirit"... and that name is Jesus (Matthew 28:19).

Themes in Matthew

Kingdom of Heaven

Of note is the phrase "Kingdom of Heaven" (ἡ βασιλεία τῶν οὐρανῶν) used often in the gospel of Matthew, as opposed to the phrase "Kingdom of God" used in other synoptic gospels such as Luke. The phrase "Kingdom of Heaven" is used 32 times in 31 verses in the Gospel of Matthew. It is speculated that this indicates that this particular Gospel was written to a primarily Jewish audience, such as the Jewish Christians, as many Jewish people of the time felt the name of God was too holy to be written. Matthew's abundance of Old Testament references also supports this theory.

The theme "Kingdom of Heaven" as discussed in Matthew seems to be at odds with what was a circulating Jewish expectation—that the Messiah would overthrow Roman rulership and establish a new reign as the new King of the Jews. Christian scholars, including N. T. Wright (The Challenge of Jesus) have long discussed the ways in which certain 1st-century Jews (including Zealots) misunderstood the sayings of Jesus—that while Jesus had been discussing a spiritual kingdom, certain Jews expected a physical kingdom. See also Jewish Messiah.

Jewish elements

While Paul's epistles and the other Gospels emphasize Jesus' international scope, Matthew addresses the concerns of a Jewish audience.[3] The cast of thought and the forms of expression employed by the writer show that this Gospel was written by a Jewish Christian of Iudaea Province. Portions of the oral sayings in Matthew contain vocabulary that indicates Hebrew or Aramaic linguistic techniques involving puns, alliterations, and word connections. Hebrew/Aramaic vocabulary choices possibly underlie the text in Matthew 1:21, 3:9, 4:12, 4:21-23, 5:9-10, 5:23, 5:47-48, 7:6, 8:28-31, 9:8, 10:35-39, 11:6, 11:8-10, 11:17, 11:29, 12:13-15, 12:39, 14:32, 14:35-36, 15:34-37, 16:18, 17:05, 18:9, 18:16, 18:23-35, 19:9-13, 19:24, 21:19, 21:37-46, 21:42, 23:25-29, 24:32, 26:28-36, 26:52.[101][102][103] The one aim pervading the book is to show that Jesus of Nazareth was the promised Messiah — he "of whom Moses in the law and the prophets did write" — and that in him the ancient prophecies had their fulfilment. This book is full of allusions to passages of the Old Testament which the book interprets as predicting and foreshadowing Jesus' life and mission. This Gospel contains no fewer than sixty-five references to the Old Testament, forty-three of these being direct verbal citations, thus greatly outnumbering those found in the other Gospels. Matthew uses Old Testament quotations out of context (as is common in Jewish writings such as the Talmud), as individual lines or even letters of Scripture were said to have inspired meanings different from the original ones.[3] The main feature of this Gospel may be expressed in the motto "I am not come to destroy [the Law and the Prophets], but to fulfill" (5:17Template:Bibleverse with invalid book). See also Expounding of the Law. It was the contention of Marcion that Christ had come to destroy the law.[104] See Biblical law in Christianity for the modern debate.

This Gospel sets forth a view of Jesus as Messiah and portrays him as an heir to King David's throne, the rightful King of the Jews. Matthew's genealogy, the wise men of the east, the massacre of the innocents, and the flight into Egypt affirm Jesus' kingship and liken him to Moses. Matthew regards Jesus as a greater Moses. He arranges Jesus' sermons into five discourses, probably parallel to the five Books of Moses, the Torah. Matthew affirms Jesus' authority to give the eternal law of Moses a new meaning.[3]

While addressing Jewish concerns, Matthew also addresses the universal nature of the church in the Great Commission (which is directed at "all nations"). See Interpretations of the Sermon on the Mount and Christian view of the Law.

Comparison with other canonical Gospels

According to Amy-Jill Levine, in Matthew (and the two other synoptic Gospels), Jesus talks more about the Kingdom of God than about himself, unlike John in which Jesus identifies himself as the true vine; the bread of life; the way, the truth and the life. Another difference is that while in Matthew and the two other synoptic gospels, Jesus teaches primarily using short parables or short sayings, in John he teaches using extended speeches. Levine states that each of the three synoptic gospels offer a distinct portraits of Jesus. For example, "Matthew has Jesus' earthly mission restricted to the 'lost sheep of the house of Israel' (Matt 15:24, see also 10:5-6) and emphasizing obedience to and preservation of biblical law. Mark however opens this mission to Gentiles and suggests abrogation of the dietary regulations mandated by the Torah."[4]

In terms of chronology Matthew agrees with the other gospels that Jesus' public ministry began with an encounter with John the Baptist. Then Matthew (and the two other synoptic Gospels) mention teaching and healing activities of Jesus in Galilee. This is followed by a trip to Jerusalem marked by an incident in the Temple. Jesus is crucified on the day of the Passover holiday. John by contrast puts the Temple incident very early in Jesus' ministry and depicts several trips to Jerusalem. The crucifixion is also placed the day before the Passover holiday, when the lambs for the Passover meal were being sacrificed in Temple.[4]

Matthew and the Didache

In modern scholarship a new consensus is emerging which dates the Didache (part of the Apostolic Fathers collection), at about the turn of the 1st century. At the same time, significant similarities between the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew have been found as these writings share words, phrases, and motifs. There is also an increasing reluctance of modern scholars to support the thesis that the Didache used Matthew. This close relationship between these two writings might suggest that both documents were created in the same historical and geographical setting. One argument that suggests a common environment is that the community of both the Didache and the Gospel of Matthew was probably composed of Judaeo-Christians from the beginning, though each writing shows indications of a congregation which appears to have alienated itself from its Jewish background (see also List of events marking the split between early Christianity and Judaism). Also, the Two Ways teaching (Did. 1-6) may have served as a pre-baptismal instruction within the community of the Didache and Matthew. Furthermore, the correspondence of the Trinitarian baptismal formula in the Didache and Matthew (Did. 7 and Matt 28:19) as well as the similar shape of the Lord's Prayer (Did. 8 and Matt 6:5-13) apparently reflect the use of resembling oral forms of church traditions. Finally, both the community of the Didache (Did. 11-13) and Matthew (Matt 7:15-23; 10:5-15, 40-42; 24:11,24) were visited by itinerant apostles and prophets, some of whom were illegitimate.[105]

In art

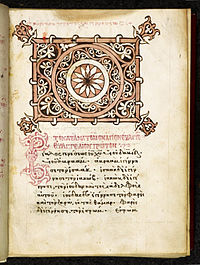

In Insular Gospel Books (copies of the Gospels produced in Ireland and Britain under Celtic Christianity), the first verse of Matthew's genealogy of Christ[106] was often treated in a decorative manner, as it began not only a new book of the Bible, but was the first verse in the Gospels.

See also

- Godspell

- Gospel harmony

- Textual variants in the Gospel of Matthew

- List of Gospels

- List of omitted Bible verses

- Gospel of the Ebionites

- Gospel of the Hebrews

- Gospel of the Nazoraeans

- Aramaic Matthew

- Great Commission

- Il vangelo secondo Matteo, a film by Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Joseph Smith—Matthew

- Olivet discourse

- Papyrus 64

- Sermon on the Mount

- Matthew 16:2b–3

- Woes of the Pharisees

- St Matthew Passion

Notes

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia > M > Gospel of St. Matthew

- ^ Kata

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. Cite error: The named reference "Harris" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Amy-Jill Levine (2001), p.373

- ^ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.59

- ^ a b c "Matthew, Gospel acc. to St." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ For a review of the debate see: Paul Foster, Why Did Matthew Get the Shema Wrong? A Study of Matthew 22:37, Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 122, No. 2 (Summer, 2003), pp. 309-333

- ^ Papias, bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor records, "Matthew collected the oracles in the Hebrew language, and each interpreted them as best he could."

- ^ Watson E. Mills, Richard F. Wilson, Roger Aubrey Bullard(2003), p.942

- ^ a b Bart Erhman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, p.44

- ^ a b Brown 1997, pp.210-211

- ^ a b Bart Erhman (2004), p. 92

- ^ a b c d e Amy-Jill Levine (2001), p.372-373

- ^ a b c Howard Clark Kee (1997), p. 448

- ^ Leon Morris, The Gospel according to Matthew Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992 p. 7

- ^ Craig S. Keener, The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2009 p.37

- ^ D. R. W. Wood, New Bible Dictionary (InterVarsity Press, 1996), 739.

- ^ Peter Kirby, Gospel of Matthew Early Christian writings

- ^ a b c d Bart Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, p.43

- ^ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.63-64

- ^ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.36

- ^ Bart Erhman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, p.80-81

- ^ Commissio Pontificia de re biblicâ, established 1902

- ^ Synoptics entry in Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ http://www.katapi.org.uk/4Gospels/Ch9.htm

- ^ Streeter, Burnett H. The Four Gospels. A Study of Origins Treating the Manuscript Tradition, Sources, Authorship, & Dates. London: MacMillian and Co., Ltd., 1924.

- ^ Pierson Parker. The Gospel Before Mark. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem: a Critical Analysis, by William R. Farmer. New York: Macmillan, 1981 Page 196

- ^ Everett Falconer Harrison, Introduction to the New Testament, Wm. Eerdmans 1971, p. 152.

- ^ Jerome (c. 347-420) was born 298 years after the crucifixion, and is reputed to be one of the great scholars of the Church. Since the 8th century he was considered to be a Father of the Church and Pius XII found him to be an indisputable witness to the mind of the Church in dealing with the Word of God

- ^ Jerome, Commentary on Matthew 2

- ^ Epiphanius (c.310-420) was the Bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, and spent most of his life battling heretics. The Panarion is particularly helpful in understanding Hebrew Christianity during a time in which the Church was moving away from its Jewish roots

- ^ Epiphanius, Panarion, XXX 3 7

- ^ Papius was born about thirty years after the crucifixion and eventually became Bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor fl. first half of the second century.

- ^ The interpretation of the above quote from Papias depends on the meaning of the term logia. The term literally means "oracles", but the intended meaning by Papias has been controversial.

- ^ Geoffrey William Bromiley, The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Publisher, p.281

- ^ Eusebius, Church History III 39 16

- ^ Irenaeus was a Christian Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, part of the Roman Empire. He was an Early Church Father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology. He was a disciple of Polycarp, who in turn was a disciple of John the Evangelist.

- ^ Irenaeus Against Heresies III 1 1

- ^ Eusebius, Church History V 10 3

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 6.25.4.

- ^ Bernhard Pick, The Gospel According to the Hebrews Publisher Kessinger Publishing, 2005, pp. 1-29

- ^ Nicholson (2009) The Gospel According to the Hebrews, BiblioBazaar, LLC, pp 25 - 26 & 82

- ^ Bernhard Pick, The Gospel According to the Hebrews, (2005) Kessinger Publishing. pp. 1-28

- ^ The Paralipomena

- ^ James R. Edwards, The Hebrew Gospel & the Development of the Synoptic Tradition, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2009 pp. 1-376

- ^ Mark 2:14

- ^ Werner G. Marx, Money Matters in Matthew, Bibliotheca Sacra 136:542 (April-June 1979):148- 57

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Saint Matthew the Evangelist

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Matthew

- ^ Mark 2:14

- ^ Matthew 9:9

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica: Saint Matthew the Evangelist

- ^ Mark 2:15–17

- ^ Luke 5:29

- ^ Acts 1:10

- ^ Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday, 2001 pp. 130-133, 201

- ^ Acts 1:14

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ James the Just

- ^ F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingston, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, Oxford University Press, 1989, p. 597&722

- ^ Matthew 2:23

- ^ Bernhard Pick, The Talmud: What It Is and What It Knows of Jesus and His Followers, Kessinger Publishing, 2006 p. 116

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 3.24.6

- ^ The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Matthew

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 6.25.4

- ^ James R. Edwards, The Hebrew Gospel & the Development of the Synoptic Tradition, (2009), Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.pp. 1-376

- ^ Jerome, Commentary on Matthew 2.12

- ^ Jerome, On Illustrious Men 3

- ^ John Bovee Dods, The Gospel of Jesus, G. Smith Pub., 1858 pp. iv - vi

- ^ Jerome, Against Pelagius 3.2

- ^ Bart Ehrman, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 43

- ^ Brown 1997, p. 172

- ^ Ehrman 2004, p. 110 and Harris 1985 both specify a range c. 80-85; Gundry 1982, Hagner 1993, and Blomberg 1992 argue for a date before 70AD.

- ^ http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/matthew.html

- ^ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/religion/story/mmmatthew.html

- ^ Foster, P. "The Epistles of Ignatius of Antioch and the Writings that later formed the NT," in Gregory & Tuckett, (2005), The Reception of the NT in the Apostolic Fathers OUP, p.186 ISBN 978-0199267828

- ^ D. Moody Smith, Matthew the evangelist, Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 9, p.5780

- ^ John A. T. Robinson (1976). Redating the New Testament. Wipf & Stock. ISBN 1579105270.

- ^ i.e. Philip Comfort and David Barret (2001) Text of the Earliest NT Greek Manuscripts.

- ^ Brown 1997, pp. 216-7; Also Carson 1992, p.66

- ^ J.K. Elliott, Novum Testamentum, Volume 38, Number 4, BRILL, 1996 , pp. 393-399

- ^ Carsten Peter Thiede, Matthew D'Ancona, Eyewitness to Jesus: amazing new manuscript evidence about the origin of the Gospels, Publisher Doubleday, 1996 PP 1-206 ISBN 0385480512, 9780385480512

- ^ James R. Edwards, The Hebrew Gospel & the Development of the Synoptic Tradition, (2009), Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.pp. 1-376

- ^ [1][2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ W. R. F. Browning, Gospel of Matthew, A dictionary of the Bible, Oxford University Press, p.245-246

- ^ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.60

- ^ Howard W. Clarke (2003), p. 1: According to Clarke, this is because some Pauline epistles give the impression that Jesus' divinity was confirmed only by his death, resurrection and ascension.

- ^ An Old Hebrew Text of St. Matthew’s Gospel, Hugh Schonfield, 1927 p. 21-22

- ^ a b Bart D. Ehrman (2004), p.121

- ^ Howard W. Clarke (2003), p. 1

- ^ David D. Kupp (1996), p.170

- ^ Scott Gregory Brown (2005), p.87

- ^ Craig Blomberg, vol. 22, Matthew, electronic ed., Logos Library System; The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2001, c1992), p.53.

- ^ Graham N. Stanton (1989), p.67

- ^ Markus Bockmuehl, Donald A. Hagner (2005), p. 191

- ^ a b Mary Clayton (1998), p.6-7

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh", Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p. 451, ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5

- ^ a b c d e Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993.

- ^ Hebrew Gospel of Matthew, George Howard, 1995, p. 184-190

- ^ Clontz, T.E. and J., "The Comprehensive New Testament with complete textual variant mapping and references for the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Nag Hammadi Library, Pseudepigrapha, Apocrypha, Plato, Egyptian Book of the Dead, Talmud, Old Testament, Patristic Writings, Dhammapada, Tacitus, Epic of Gilgamesh", Cornerstone Publications, 2008, p. 439-498, ISBN 978-0-977873-71-5

- ^ An Old Hebrew Text of St. Matthew’s Gospel, Hugh Schonfield, 1927, p.160

- ^ Epiphanius:Panarion: No.42

- ^ H. van de Sandt (ed), Matthew and the Didache, ( Assen: Royal van Gorcum; Philadelphia: Fortress Press , 2005).

- ^ Matthew 1:18

References

- Blomberg, Craig L., Matthew, The New American Commentary 22. Broadman, 1992.

- Bockmuehl, Markus and Donald A. Hagner, The Written Gospel, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0521832853.

- Pierre Bonnard, L'Évangile selon saint Matthieu, Labor et Fides, 2002.

- Brown, Raymond E., Introduction to the New Testament, Anchor Bible, 1997, ISBN 0-385-24767-2.

- Brown, Scott Gregory, Mark's Other Gospel: Rethinking Morton Smith's Controversial Discovery, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2005, ISBN 0889204616.

- Carson, D.A., Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris: An introduction to the New Testament Apollos, 1992, ISBN 085111766X.

- Clarke, Howard W., Howard W. Clarke, The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers, Indiana University Press, 2003.

- Clayton, Mary, The Apocryphal Gospels of Mary in Anglo-Saxon England, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0521581680.

- Davies, W. D., and Dale C. Allison: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew, Continuum International Publishing Group, 1997 ISBN 056708518X.

- Ehrman, Bart D., Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford, (2004), ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

- Green, Michael, The Message of Matthew. The Kingdom of Heaven. Bible Speaks Today. InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove 2001 ISBN 0-8308-1243-1.

- Gundry, Robert Horton: Matthew, a Commentary on His Literary and Theological Art, W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1982, ISBN 080283549X.

- Hagner, Donald Alfred, Matthew 1-13 Word Biblical Commentary, Word Books, 1993.

- Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible, Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985.

- Howard Clark Kee, part 3, The Cambridge Companion to the Bible, Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Kupp, David D., Matthew's Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God's People in the First, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0521570077.

- Amy-Jill Levine, chapter 10, The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Mills, Watson E., Richard F. Wilson and Roger Aubrey Bullard, Mercer Commentary on the *New Testament, Mercer University Press, 2003.

- John Nolland, The Gospel of Matthew, NIGTC, 2005. 1,579 pages. ISBN 978-0-8028-2389-2

- Pick, Bernhard, The Gospel According to the Hebrews, Publisher Kessinger Publishing, 2005.

- Saldarini, Anthony J., Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, Editors: James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, ISBN 0802837115

- Stevenson, Kenneth. The Lord's prayer: a text in tradition, Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 0800636503.

- Stanton, Graham N., The Gospels and Jesus, Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Thiede, Carsten Peter, Papyrus Magdalen Greek 17 (Gregory–Aland P64) 1995. A Reappraisal" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 105: 13–20. [12] Retrieved 2006-12-13.

- Thiede, Carsten Peter (EngTrans. D'Ancona), Eyewitness to Jesus: amazing new manuscript evidence about the origin of the Gospels, Doubleday, 1996, ISBN 0385480512

External links

- A list of online translations of the Gospel of Matthew: Matthew 1–28

- A textual commentary on the Gospel of Matthew Detailed text-critical discussion of the 300 most important variants of the Greek text (PDF, 438 pages).

- Early Christian Writings Gospel of Matthew: introductions and e-texts.