Isma'ilism: Difference between revisions

oops |

okay |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{for|the Egyptian city|Ismaïlia}} |

{{for|the Egyptian city|Ismaïlia}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Ismailis}} |

{{Ismailis}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

'''{{unicode|Ismāʿīlism}}''' ([[Arabic language|Arabic]]: الإسماعيليون ''{{unicode|al-Ismāʿīliyyūn}}''; [[Persian language|Persian]]: اسماعیلیان ''{{unicode|Esmāʿiliyān}}''; [[Urdu]]: إسماعیلی ''{{unicode|Ismāʿīlī}}'') is a branch of [[Shia Islam]]. It is the second largest sect of Shiaism, after the mainstream [[Twelvers]] (''{{unicode|Ithnāʿashariyya}}''). The {{unicode|Ismāʿīlī}} get their name from their acceptance of [[Ismail bin Jafar|{{unicode|Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar}}]] as the divinely appointed spiritual successor ''([[Shi'a Imam|{{unicode|Imām}}]])'' to [[Jafar al-Sadiq|{{unicode|Jaʿfar aṣ-Ṣādiq}}]], wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who accept [[Musa al-Kazim|{{unicode|Mūsà al-Kāżim}}]], younger brother of {{unicode|Ismāʿīl}}, as the [[Imamah (Shi'a Ismaili doctrine)|true {{unicode|Imām}}]]. |

'''{{unicode|Ismāʿīlism}}''' ([[Arabic language|Arabic]]: الإسماعيليون ''{{unicode|al-Ismāʿīliyyūn}}''; [[Persian language|Persian]]: اسماعیلیان ''{{unicode|Esmāʿiliyān}}''; [[Urdu]]: إسماعیلی ''{{unicode|Ismāʿīlī}}'') is a branch of [[Shia Islam]]. It is the second largest sect of Shiaism, after the mainstream [[Twelvers]] (''{{unicode|Ithnāʿashariyya}}''). The {{unicode|Ismāʿīlī}} get their name from their acceptance of [[Ismail bin Jafar|{{unicode|Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar}}]] as the divinely appointed spiritual successor ''([[Shi'a Imam|{{unicode|Imām}}]])'' to [[Jafar al-Sadiq|{{unicode|Jaʿfar aṣ-Ṣādiq}}]], wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who accept [[Musa al-Kazim|{{unicode|Mūsà al-Kāżim}}]], younger brother of {{unicode|Ismāʿīl}}, as the [[Imamah (Shi'a Ismaili doctrine)|true {{unicode|Imām}}]]. |

||

Revision as of 08:06, 6 April 2010

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

Ismāʿīlism (Arabic: الإسماعيليون al-Ismāʿīliyyūn; Persian: اسماعیلیان Esmāʿiliyān; Urdu: إسماعیلی Ismāʿīlī) is a branch of Shia Islam. It is the second largest sect of Shiaism, after the mainstream Twelvers (Ithnāʿashariyya). The Ismāʿīlī get their name from their acceptance of Ismāʿīl ibn Jaʿfar as the divinely appointed spiritual successor (Imām) to Jaʿfar aṣ-Ṣādiq, wherein they differ from the Twelvers, who accept Mūsà al-Kāżim, younger brother of Ismāʿīl, as the true Imām.

Tracing its earliest theology to the lifetime of Muḥammad, Ismāʿīlism rose at one point to become the largest branch of Shī‘ism, climaxing as a political power with the Fatimid Empire in the tenth through twelfth centuries.[1] Ismailis believe in the oneness of God, as well as the closing of divine revelation with Muḥammad, whom they see as the final prophet and messenger of God to all humanity. The Ismāʿīlī and the Twelvers both accept the same initial A'immah from the descendants of Muḥammad through his daughter Fāṭimah az-Zahra and therefore share much of their early history. Both Shī‘ite groups see the family of Muḥammad (Ahl al-Bayt) as divinely chosen, infallible (ismah), and guided by God to lead the Islamic community (Ummah), a belief that distinguishes them from the majority Sunni branch of Islam.

After the death—or Occultation according to Seveners—of Muhammad ibn Ismail in the 8th century CE, the teachings of Ismailism further transformed into the belief system as it is known today, with an explicit concentration on the deeper, esoteric meaning (batin) of the Islamic religion. With the eventual development of Twelverism into the more literalistic (zahir) oriented Akhbari and later Usooli schools of thought, Shi'ism developed into two separate directions: the metaphorical Ismāʿīlī group focusing on the mystical path and nature of Allah, with the "Imām of the Time" representing the manifestation of truth and reality, with the more literalistic Twelver group focusing on divine law (sharia) and the deeds and sayings (sunnah) of Muhammad and the Twelve Imams who were guides and a light to God.[2]

Though there are several paths (tariqah) within the Ismāʿīlīs, the term in today's vernacular generally refers to the Nizari path, which recognizes the Aga Khan as the 49th hereditary Imam and is the largest group among the Ismāʿīlīs. While some of the branches have extremely differing exterior practices, much of the spiritual theology has remained the same since the days of the faith's early Imāms. In recent centuries Ismāʿīlīs have largely been an Indo-Iranian community,[3] but Ismāʿīlī are found in India, Pakistan, Syria, Saudi Arabia[4], Yemen, China[5], Jordan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, East Africa, Syria, and South Africa, and have in recent years emigrated to Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America.[6]

History

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

Succession crisis

Ismailism shares its beginnings with other early Shī‘ah sects that emerged during the succession crisis that spread throughout the early Muslim community.

From the beginning, the Shī‘ah asserted the right of ‘Alī, Muhammad's cousin, to have both political and spiritual control over the community. This also included his two sons, who were the grandsons of Muhammad through his daughter Fāṭimatu z-Zahrah.

The conflict remained relatively peaceful between the partisans of ‘Alī and those who asserted a semi-democratic system of electing caliphs, until the third of the Rashidun caliphs, Uthman was killed, and ‘Alī, with popular support, ascended to the caliphate.[7]

Soon after his ascendancy, Aisha, the third of the Prophet's wives, claimed along with Uthman's tribe, the Ummayads, that Ali should take Qisas (blood for blood) from the people responsible for Uthman's martyrdom. ‘Alī voted against it as he believed that situation at that time demanded a peaceful resolution of the matter. Both parties could rightfully defend their claims, but due to escalated misunderstandings, the Battle of the Camel was fought and both parties bore losses but soon reached an agreement.

Following this battle, Muawiya, the Umayyad governor of Syria, also staged a revolt under the same pretences. ‘Alī led his forces against Muawiya until the side of Muawiya held copies of the Quran against their spears and demanded that the issue be decided by Islam's holy book. ‘Alī accepted this, and an arbitration was done which ended in his favor.[8]

A group among Alī's army believed subjecting his legitimate authority to arbitration was tantamount to apostasy, and abandoned his forces. This group was known as the Kharijites, and ‘Alī wished to defeat their forces before they reached the cities where they would be able to blend in with the rest of the population. He was unable to do this, but nonetheless defeated their forces in the battles following afterward.[9]

Regardless of these defeats, the Kharijites survived and became a violently problematic group in Islamic history. After plotting an assassination against ‘Alī, Muawiya, and the arbitrator of their conflict, only ‘Alī was successfully assassinated in 661 CE, and the Imāmate passed on to his son Hasan and then later his son Husayn, or according to the Nizari Ismāʿīlī, straight to Husayn. However, the political caliphate was soon taken over by Muawiya who was the only leader in the empire at that time with an army large enough to seize control.[10]

Karbala and afterward

The Battle of Karbala

After the passing away of Hassan, Husayn and his family were increasingly worried about the religious and political persecution that was becoming commonplace under the reign of Muawiya's son, Yazid. Amidst this turmoil in 680 CE, Husayn along with the women and children of his family, upon receiving invitational letters and gesture of support by Kufis, wished to go to Kufa and confront Yazid as an intercessor on part of the citizens of the empire. However, he was stopped by Yazid's army in Karbala, during the month of Muharram. His family was starved and deprived of water and supplies, until eventually the army came in on the tenth day and killed Husayn and his companions, and enslaved the rest of the women and family, taking them to Kufa.[11]

This battle would become extremely important to the Shī‘ah psyche. The Twelvers, as well as Mustaali Ismāʿīlī still mourn this event during a holiday known as Ashura. The Nizari Ismāʿīlī however do not mourn this event because of the belief that the light of the Imām never dies but rather passes on to the succeeding Imām, making mourning arbitrary.

The beginnings of Ismāʿīlī Daʿwah

After being set free by the caliph Yazid, Zainab, the daughter of Fāṭimatu z-Zahra' and ‘Alī and the sister of Hassan and Husayn, started to spread the word of Karbala to the Muslim world, making speeches regarding the event. This was the first organized Daʿwah of the Shī‘ah community, which would later develop into an extremely spiritual institution for the Ismāʿīlīs.

After the poisoning of ‘Alī al-Sajjad by Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik in 713 CE, Shiism's first succession crisis rose with Zayd ibn ‘Alī's companions and the Zaydī Shī‘ah that claim Zayd ibn ‘Alī as the Imām, whilst the rest of the Shī‘ah maintained Muhammad al-Baqir as the Imām. The Zaidis argued that any sayed, descendant of Muhammad through Hassan or Husayn, who rebelled against tyranny and the injustice of his age, can be the Imām. The Zaidis created the first Shī‘ah states in Iran, Iraq and Yemen.

In contrast to his predecessors, Muhammad al-Baqir focused on academic Islamic scholarship in Medina, where he promulgated his teachings to many Muslims, both Shī‘ah and non-Shī‘ah, in an extremely organized form of Daʿwah.[12] In fact, the earliest text of the Ismaili school of thought is said to be the "Umm al-kitåb" (The Archetypal Book), a conversation between Muhammad al-Baqir and three of his disciples.[13]

This tradition would pass on to his son, Ja'far al-Sadiq, who inherited the Imāmate on his father's death in 743. Ja'far al-Sadiq excelled in the scholarship of the day and had many pupils, including three of the four founders of the Sunni madhabs.[14]

However, following Jaffir's poisoning in 765, a fundamental split would occur in the community. Isma'il bin Jafar, who at one point seemed to be heir apparent, apparently predeceased his father in 755. While Twelvers either argue he was never heir apparent or that he truly predeceased his father hence Musa al-Kadhim was the true heir to the Imamate, Ismāʿīlīs argue that either the death was staged in order to draw harm away from al-Sadiq's successor or that his early death does not mean he was not an Imām, and rightfully the Imāmate would pass to his son, Muhammad ibn Ismail.

Ascension of the Dais

For the Sevener Ismāʿīlī, the Imāmate ended with Isma'il ibn Ja'far, whose son Muhammad ibn Ismail was the expected Mahdi that Ja'far al-Sadiq had preached about. However, at this point the Ismāʿīlī Imāms according to the Nizari and Mustaali found areas where they would be able to be safe from the recently founded Abbasid Empire which had defeated and seized control from the Umayyads in 750 AD.[15]

At this point, much of the Ismaili community believed that Muhammad ibn Ismail had gone into the Occultation and that he would one day return. With the status and location of the Imāms not known to the community, Ismailism began to propagate the faith through Dāʿiyyūn from its base in Syria. This was the start of the spiritual beginnings of the Daʿwah that would later blossom on the Mustaali branch of the faith, as well as play important parts in the other three branches.[16]

The Da'i was not a missionary in the typical sense, and he was responsible for both the conversion of his student as well as the mental and spiritual wellbeing. The Da'i was a guide and light to the Imām. The student and teacher relationship of the Da'i and his student was much like the one that would develop in Sufism. The student desired God, and the Da'i could bring him to God by making him recognize the stature and light of the Imām descended from the Imāms, which in turn descended from God. The Da'i was the path, and the Face of God which was a Qur'anic term the Ismāʿīlī took to represent the Imām, was the destination.[15]

Shams Tabrizi and Rumi is a famous example of the importance between the guide and the guided, and Rumi dedicated much of his literature to Shams Tabrizi and his discovery of the truth.

The Qarmatians

While many of the Ismāʿīlī were content with the Dai teachings, a group that mingled Persian nationalism and Zoroastrianism with Ismāʿīlī teachings surfaced known as the Qarmatians. With their headquarters in Bahrain, they accepted a young Persian former prisoner by the name of Abu'l-Fadl al-Isfahani, who claimed to be the descendant of the Persian kings[17][18][19][20][21][22][23] as their Mahdi, and rampaged across the Middle-East in the tenth century, climaxing their violent campaign with the stealing of the Black Stone from the Kaaba in Mecca in 930 under Abu Tahir Al-Jannabi. Following the arrival of the Mahdi they changed their qiblah from the Kaaba to the Zoroastrian-influenced fire. After their return of the Black Stone in 951 and a defeat by the Abbasids in 976 they slowly dwindled and no longer have any adherents.[24]

The Fatimid Empire

Rise of the Fatimid Empire

The political asceticism practiced by the Imāms during the period after Muhammad ibn Ismail was to be short lived and finally concluded with the Imāmate of Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi Billah, who was born in 873. After decades of Ismāʿīlīs believing that Muhammad ibn Ismail was in the Occultation and would return to bring an age of justice, al-Mahdi taught that the Imāms had not been literally secluded, but rather had remained hidden to protect themselves and had been organizing the Da'i, and even acted as Da'i themselves. He taught that during the supposed Occultation of Muhammad ibn Ismail, many of Muhammad ibn Ismail's descendants lived as Imāms secluded from the community, guiding them through the Da'i at times even taking the guise of Da'i.

After raising an army and successfully defeating the Alghabids in North Africa and a number of other victories, al-Mahdi Billah successfully established a Shi'ah political state ruled by the Imāmate in 910 AD.[25] This was the only time in history where the Shi'a Imamate and Caliphate were united after the first Imam, Ali ibn Abu Talib.

In parallel with the dynasty's claim of descent from ‘Alī and Fāṭimatu z-Zahrah, the empire was named “Fatimid.” However, this was not without controversy and with the extent that Ismāʿīlī doctrine had spread, the Abbasid caliphate assigned Sunni and Twelver scholars with the assignment to disprove the lineage of the new dynasty. This became known as the Baghdad Manifesto, and it traces the lineage of the Fatimid dynasty to a Jewish blacksmith. Its authenticity has been both questioned and supported by various Islamic scholars.[citation needed]

The Middle-East under Fatimid rule

The Fatimid Empire expanded quickly under the subsequent Imāms. Under the Fatimids, Egypt became the center of an empire that included at its peak North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Syria, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Yemen and the Hejaz. Under the Fatimids, Egypt flourished and developed an extensive trade network in both the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, which eventually determined the economic course of Egypt during the High Middle Ages.

The Fatimids promoted two ideas that were radical for that time. The first was promotion by merit rather than genealogy. The second was religious toleration, under which both Jews and Coptic Christians flourished.[citation needed]

Also during this period the three contemporary branches of Ismailism formed. The first branch (Druze) occurred with the Imām Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah. Born in 985, he ascended as ruler at the age of eleven and was feared for his eccentricity and believed insanity. The typical religiously tolerant Fatimid Empire saw much persecution under his reign. When in 1021 his mule returned without him, soaked in blood, a religious group that was even forming in his lifetime broke off from mainstream Ismailism and refused to acknowledge his successor. Later to be known as the Druze, they believe Al-Hakim to be the manifestation of God and the prophecized Mahdi, who would one day return and bring justice to the world.[26] The faith further split from Ismailism as it developed very unique doctrines which often classes it separately from both Ismailism and Islam.

The second split occurred following the death of Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah in 1094. His rule was the longest of any caliph in both the Fatimid and other Islamic empires. Upon his passing away his sons, the older Nizar and the younger Al-Musta'li fought for political and spiritual control of the dynasty. Nizar was defeated and jailed, but according to Nizari tradition his son escaped to Alamut where the Iranian Ismāʿīlī had accepted his claim.[27]

The Mustaali line split again between the Taiyabi and the Hafizi, the former claiming that the 21st Imām and son of Al-Amir went into occultation and appointed a Dāʿī al-Muṭlaq to guide the community, in a similar manner as the Ismāʿīlī had lived after the death of Muhammad ibn Ismail. The latter claimed that the ruling Fatimid caliph was the Imām. However, in the Mustaali branch, the Dai came to have a similar but more important task. The term Dāˤī al-Mutlaq (Template:Lang-ar) literally means "the absolute or unrestricted missionary". This dai was the only source of the Imām's knowledge after the occultation of al-Qasim in Mustaali thought.

According to Tayyabī Mustaˤlī Ismā'īlī tradition, after the death of Imām al-Amīr, his infant son, AtTaiyab abi-l-Qasim, about 2 years old, was protected by the most important woman in Musta'li history after Prophet's daughter Fāṭimatu z-Zahrah. She was al-Malika al-Sayyida (Hurratul-Malika), which was a Queen in Yemen. She was promoted to the post of hujja long before by Imām Mustansir at the death of her husband and she now ran the dawat from Yemen in the name of Imaam Tayyib. She was instructed and prepared by Imām Mustansir and following Imāms for the second period of Satr. It was going to be on her hands, that Imām Tayyib would go into seclusion, and she would institute the office of Dāˤī al-Mutlaq. Syedna Zueb-bin-Musa was first to be instituted to this office and the line of Tayyib Dais that began in 1132 have passed from one Dai to another and is continuing till date.

The Mustaali split several times over disputes regarding who was the rightful Dāʿī al-Muṭlaq, the leader of the community within The Occultation.

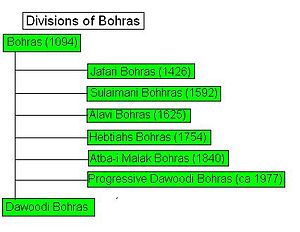

After 27 th dai Dawood bin qutub shah there is split ,follower of dawood called Dawoodi bohra and follower of Suleman called sulemani. Dawoodi bohra 's present 52nd Dai is Syedna mohd. Burhanuddin and following same tradition of fatimid era. The Sulaimani Bohra are mostly concentrated in Yemen and Saudi Arabia with some communities in the Indian Subcontinent. The Dawoodi Bohra and Alavi Bohra are mostly exclusive to the Indian Subcontinent. Other groups include Atba-i-Malak and Hebtiahs Bohra. Mustaali beliefs and practices, unlike those of the Nizari and Druze, are generally compatible with mainstream Islam, representing a continuation of Fatimid tradition and fiqh'.

Decline of the empire

In the 1040s, the Zirids (governors of North Africa under the Fatimids) declared their independence from the Fatimids and their conversion to Sunni Islam, which led to the devastating Banu Hilal invasions. After about 1070, the Fatimid hold on the Levant coast and parts of Syria was challenged by first Turkish invasions, then the Crusades, so that Fatimid territory shrunk until it consisted only of Egypt. [citation needed]

After the decay of the Fatimid political system in the 1160s, the Zengid ruler Nūr ad-Dīn had his general, Saladin, seize Egypt in 1169, forming the Sunni Ayyubid Dynasty. This signaled the end of the Hafizi Mustaali branch of Ismailism as well as the Fatimid Empire.

Alamut

Hassan-i-Sabbah

Very early in the empire's life, the Fatimids sought to spread the Ismāʿīlī faith which in turn would spread loyalties to the Imāmate in Egypt. One of their earliest attempts would be taken by a Dai by the name of Hassan-i-Sabbah.

Hassan-i-Sabbah was born into a Twelver family living in the scholarly city of Qom in 1056 AD. His family later relocated to the city of Tehran which was an area with an extremely active Ismāʿīlī Daʿwah. He immersed himself in Ismāʿīlī thought, however he did not choose to convert until he was overcome with an almost fatal illness, where he finally feared dying without knowing the Imām of his time.

Afterwards, Hassan-i-Sabbah became one of the most influential Dais in Ismāʿīlī history, and would be important to the survival of the Nizari branch of Ismailism, which today is its largest branch.

Legend holds that he met with Imām Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah and asked him who his successor would be, to which he responded, his eldest son Nizar.

Hassan-i-Sabbah would continue his Dai activities and they would climax with his taking of Alamut. Taking two years, he first converted most of the surrounding villages to Ismailism. Afterwards, he converted most of the staff to Ismailism and then took over the fortress, and presented the current leader with payment for the fortress. With no choice, the leader abdicated and Hassan-i-Sabbah turned Alamut into an outpost of Fatimid rule within Abbasid territory.

The Hashashin

Surrounded by the Abbasids and other hostile powers, and low in numbers, Hassan-i-Sabbah derived a way to attack the Ismāʿīlī enemies with a small loss and number. Using the method of assassination, from which the English word is derived from Hashashin, he ordered the killing of Sunni scholars and politicians that threatened the Ismāʿīlīs. Knives and daggers were used. Sometimes, in warning, a knife would be put into the pillow of the enemy and often they understood the message.[28]

However, when an assassination was actually made the Hashashin would not be allowed to run away, but rather to strike further fear in the enemy by showing no emotion, they would stand there. This further increased the reputation of the Hashashin in the Sunni world.[28]

Amin Maalouf, in his novel Samarkand, disputes the origin of the word assassin. According to him it is not derived from the name of the drug hashish which Westerners used to believe the sect took. Instead he proposes this story was fabricated by Orientalists to explain how faithfully the Ismāʿīlīs would carry out these suicide-assassinations without fearing death. Maalouf suggests that the term is derived from the word assaas (foundation), and Assassiyoon, meaning "those faithful to the foundation." [29]

Threshold of the Imāmate

After the imprisonment of Nizar by his younger brother Mustaal, it is claimed Nizar's son al-Hādī survived and fled to Alamut. He was offered a safe place in Alamut where Hassan-i-Sabbah welcomed him. However, it is believed this was not announced to the public and the lineage was hidden until a few Imāms later.[28]

It was announced with the advent of Imām Hassan II, who some historians believe to be a descendant of the leaders of Alamut and not of Nizar. In a show of his Imāmate and to emphasize the interior meaning (the batin) over the exterior meaning (the zahir) he prayed with his back to Mecca, as did the rest of the congregation which prayed behind him, and ordered the community to break their Ramadan fasting with a feast at noon. He made a speech saying he was in communication with the Imām, which many of the Ismāʿīlīs understood to mean he was the Imām himself.[28]

Afterwards his descendants would rule as the Imāms at Alamut until its destruction by the Mongols.

Destruction by the Mongols

The stronghold at Alamut, though it had warded off the Sunni attempts to take it several times, including one by Saladin, would soon meet with destruction. By 1206, Genghis Khan had managed to unite many of the once antagonistic Mongol tribes into a ruthless, but nonetheless unified, force. Using many new and unique military techniques, Genghis Khan led his Mongol hordes across Central Asia into the Middle-East where they won a series of tactical military victories using a scorched-earth policy.

A grandson of Genghis Khan, Hulagu Khan, led the devastating attack on Alamut in 1256, only a short time before he would sack the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad in 1258. As he would later do to the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, he destroyed Ismāʿīlī as well as Islamic religious texts. The Imāmate that was located in Alamut along with its few followers were forced to flee and take refuge elsewhere.

Aftermath

After the fall of the Fatimid Empire and its bases in Iran and Syria, the three currently living branches of Ismāʿīlī generally developed geographically isolated from each other, with the exception of Syria (which has both Druze and Nizari) and Pakistan and rest of South Asia (which had both Mustaali and Nizari).

The Nizari kept large populations in Syria, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, and has smaller populations in China and Iran. This community is the only one with a living Imām, who is titled today as the Aga Khan.

The Druze mainly settled in Syria and Lebanon, and developed a community based upon the principles of reincarnation through their own descendants. Their leadership is based through community scholars, who are the only individuals allowed to read their holy texts. It is controversial whether this group falls under the classification of Ismāʿīlīsm or Islam because of their unique beliefs.

Beliefs

View on the Qur'an

The Ismāʿīlīs believe the Qur'an has several layers of meaning, but they generally divide those types of meanings into two: the apparent (zahir) meaning and the hidden (batin) meaning. While a believer can understand the batin meaning to some extent, the ultimate interpretation lies in the office of the Imāmate. The Imām's farmans (teachings) are binding upon the community. In this way, the Ismāʿīlī community can adapt to new times and new places. Often times, the Imam of the Time is known as the "Bolta Quran" (the "speaking Qur'an"), meaning that he reinterprets the literary text in a way that can be understood for today's times.

This belief contrasts the Ismāʿīlīs from Sunni Muslims, who cite the following Qur'anic verse: "So as for those in whose hearts there is a deviation (from the truth) they follow that which is not entirely clear thereof, seeking Al-Fitnah (trials & tribulations), and seeking for its hidden meanings, but none knows its hidden meanings except Allah." (3:7)

The Ginans

The Ginans are Nizari Ismā‘īlī religious texts. They are written in the form of poetry by Pirs to interpret the meanings of Qur’anic ayat into the languages of the Indian subcontinent, especially Gujarati and Urdu. In comparison to Ginans, Ismāʿīlīs of other origins, such as Persians, Arabs, and Central Asians have qasidas (Template:Lang-ar) written by missionaries. See Works of Pir Sadardin

Reincarnation

Reincarnation exists in the Druze branch of Ismailism. The Druze believe that members of their community can only be reincarnated within the community. It is also known that Druze believe in five cosmic principles, represented by the five colored Druze star: intelligence/reason (green), soul (red), word (yellow), precedent (blue), and immanence (white). These virtues take the shape of five different spirits which, until recently, have been continuously reincarnated on Earth as prophets and philosophers including Adam, the ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer Pythagoras, and the ancient Pharaoh of Egypt Akhenaten, and many others. The Druze believe that, in every time period, these five principles were personified in five different people who came down together to Earth to teach humans the true path to God and nirvana, but that with them came five other individuals who would lead people away from the right path into "darkness".

Numerology

Ismāʿīlīs believe numbers have religious meanings. The number seven plays a general role in the theology of the Ismā'īliyya, including mystical speculations that there are seven heavens, seven continents, seven orifices in the skull, seven days in a week, and so forth.

Imamate

In Nizari Ismailism, the Imām is seen through the Qur'anic phrase, “The Face of God.” The Imām is truth and reality itself, and hence he is their path of salvation to God.[30]

Sevener Ismāʿīlī doctrine holds that divine revelation had been given in six periods (daur) entrusted to six prophets, who they also call Natiq (Speaker), who were commissioned to preach a religion of law to their respective communities.

Whereas the Natiq was concerned with the rites and outward shape of religion, the inner meaning is entrusted to a Wasi (Representative). The Wasi would know the secret meaning of all rites and rules and would reveal them to a small circles of initiates.

The Natiq and the Wasi are in turn succeeded by a line of seven Imāms, who would guard what they received. The seventh and last Imām in any period would in turn be the Natiq of the next period. The last Imām of the sixth period however would not bring about a new religion of law but supersede all previous religions, abrogate the law and introduce din Adama al-awwal ("the original religion of Adam") practised by Adam and the Angels in paradise before the fall, which would be without cult or law but consist merely in all creatures praising the creator and recognizing his unity. This final stage was called Qiyamah.[31]

Pir and Dawah

Just as the Imām is seen by Ismailis as the Face of God, God's avatar within reality, the guide to the avatar is known as the Dai. During the period between the Imāmates of Muhammad ibn Ismail and al-Madhi Billah, the relationship between the teacher and the student became a sacred one, and the Dai became a position much beyond a normal missionary. The Dai passed on the sacred and hidden knowledge of the Imām to the student who could then use that information to ascend to higher levels. First the student loved the Dai, and from the Dai he learned to love the Imām, who was but a manifestation of God. In Nizari Ismailism, the head Dai is called the Pir.[15].

Zahir

In Ismailism, things have an exterior meaning, what is apparent. This is called zahir.

Batini

In Ismailism, things have an interior meaning that is reserved for a special few who are in tune with the Imām, or are the Imām himself. This is called batin.

Aql

As with other Shī‘ah, Ismāʿīlīs believe that the understanding of God is derived from the first light in the universe, the light of Aql, which in Arabic roughly translates as knowledge. It is through this knowledge that all living and non-living entities know God, and all of humanity is dependent and united in this light.[28] [32] Contrastingly, in Twelver thought this includes the Prophets as well, especially Muhammad who is the greatest of all the incarnations of Aql.

Taqiyya

Ismāʿīlīs believe in the Shi'ite doctrine of taqiyya, which means to hide one's true religious beliefs. This doctrine, which is not found in Sunni theology, has been pivotal to the survival of Ismāʿīlī groups since they have been small minorities in many countries and empires hostile to them.

Seven Pillars

Walayah

A pillar which translates from Arabic as “guardianship.” It denotes, “Love and devotion for God, the Prophets, the Imām, and the Dai.” In Ismāʿīlī doctrine, God is the true desire of every soul, and he manifests himself in the forms of Prophets and Imāms, and to be guided to his path, one requires a messenger or a guide: a Dai.

Taharah or Shahada

Taharah

A pillar which translates from Arabic as “purity.” The Druze do not believe in this pillar and instead substitute shahada in its place.

Shahada

In place of Taharah, the Druze have the Shahada, or affirmation of faith.

Salah

A pillar which translates from Arabic as “prayer.” Unlike Sunni and Twelver Muslims, Nizari Ismai'lis do not follow the mainstream Islamic practice in regards to the number of daily prayers. Nizari Ismai'lis believe that it is up to the Imām of the time to designate the style and form of prayer, and for this reason current Nizari prayer resembles a dua (supplication) and is recited three times a day. These three times have been related with the three prayer times mentioned in the Qur'an, i-e, Sunrise, before Sunset, and After Sunset. In this regard, Ismaili's believe, the Imām of the time has the right to amend the prayers according to the needs of the time. The Druze, who also choose not to follow Islamic shari'ah (legal code), attribute a solely metaphorical meaning to salah. In contrast, the Mustaali (Bohra) branch of Ismailism has kept five prayers and their style is generally closely related to Twelver groups.

Zakah

A pillar which translates as “charity.” With the exception of the Druze sect, all Ismāʿīlīs form of zakat resembles mainstream Muslims. The Twelvers, pay khums which is 1/5 of one's unspent money at the end of the year. Ismāʿīlīes,also pay the tithe of 12.5% which is re used it furthering development projects in the eastern world, which benefit not only Ismailis but also the many other communities living in that area.

Sawm

A pillar which translates as “fasting.” Mainstream Sunni and Shi'ite Muslims fast by abstaining from food, drink and sexual relations with one's spouse from dawn to sunset for 30 days during the holy month of Ramadan (9th month of the Islamic calendar). In contrast, the Nizari and Mustaali believe in a metaphorical as well as a literal meaning of fasting. The literal meaning is that one must fast as an obligation, such as during Ramadan, and the metaphorical meaning being that one is in attainment of the Divine Truth and must strive to avoid worldy activities which may detract from this goal. In particular, Ismāʿīlīs believe that the esoteric meaning of fasting involves a the "fasting of soul," whereby they attempt to purify the soul simply by avoiding sinful acts and doing good deeds, etc. In addition, the Nizari also fast on "Shukravari Beej" which falls on a Friday that coincides with the New Moon.

Hajj

A pillar which translates from Arabic as “pilgrimage", it is the pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is currently the largest annual pilgrimage in the world and is the fifth pillar of Islam, a religious duty that must be carried out at least once in one's lifetime by every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so. Ismaili sects do not ascribe to mainstream Islamic beliefs regarding the Hajj, considering it instead to metaphorically mean visiting the Imam himself, that being the greatest and most spiritual of all pilgrimages. However, as the Druze do not follow shariah, they do not believe in a literal pilgrimage to the Kaaba in Mecca like other Muslims do, while the Mustaali still hold on to the literal meaning as well.[30]

Jihad

An Islamic term, Jihad is a religious duty of Muslims. In Arabic, the word jihād is a noun meaning "struggle." Jihad appears frequently in the Qur'an and common usage as the idiomatic expression "striving in the way of God (al-jihad fi sabil Allah)". A person engaged in jihad is called a mujahid; the plural is mujahideen.

A minority among the Sunni scholars sometimes refer to this duty as the sixth pillar of Islam, though it occupies no such official status. In Twelver Shi'a Islam, however, Jihad is one of the 10 Practices of the Religion.

In western societies, the term jihad is often mistranslated as "holy war". Muslim authors tend to reject such an approach stressing also the non-militant connotations of the word. In technical literature regarding the concept of jihad the term "holy war" has often been used to describe it. However, scholars of Islamic studies often reject this association, stressing that the two terms are not synonymous.

Branches

Estimates on the total Ismai'li population range from 15–20 million.[1] It is accepted that Ismai'lis constitute the second-largest Shi'a Muslim population. Within the Ismai'li sub-sect, the largest branch is Nizari with 18 Million. With its branches added together, the Mustaali are the second largest at 1-2 million, followed by the Druze at around 350,000 to 1 million.

Nizari

The largest part of the Ismāʿīlī community today accepts Prince Karim Aga Khan IV as their 49th Imām[33], whom Ismāʿīlīs claim to be descended from Muḥammad through his daughter Fāṭimah az-Zahra and 'Ali, Muḥammad's cousin and son-in-law. This claim is dismissed by Sunni scholars and academics who cite the Qur'anic verse in refutation: "Muhammad is not the father of any of your men, but (he is) the Messenger of Allah, and the Seal of the Prophets, and Allah has full knowledge of all things." (33:40) The 46th Ismāʿīlī Imām, Aga Hassan ‘Alī Shah, fled Iran in the 1840s after a failed coup against the Shah of the Qajar dynasty.[34] Aga Hassan ‘Alī Shah settled in Mumbai in 1848.[34]

Like its predecessors, the present constitution is founded on each Ismāʿīlī's spiritual allegiance to the Imām of the Time (Imām az-Zamān), which is separate from the secular allegiance that all Ismāʿīlīs owe as citizens to their national entities. The present Imām and his predecessor emphasized Ismāʿīlīs' allegiance to their country as a fundamental obligation. These obligations discharged not by passive affirmation but through responsible engagement and active commitment to uphold national integrity and contribute to peaceful development.

In view of the importance that Islām places on maintaining a balance between the spiritual well-being of the individual and the quality of his life, the Imām's guidance deals with both aspects of the life of his followers. The Aga Khan has encouraged Ismāʿīlis settled in the industrialized world to contribute towards the progress of communities in the developing world through various development programmes. In recent years, Nizari Ismāʿīlīs, who have come to the US, Canada and Europe, many as refugees from Asia and Africa, have readily settled into the social, educational and economic fabric of urban and rural centres across the two continents. As in the developing world, the Nizari Ismāʿīlī community's settlement in the industrial world has involved the establishment of community institutions characterized by an ethos of self-reliance, an emphasis on education, and a spirit of philanthropy.

Mustaali

In time, the seat for one chain of the Dai was split between India and Yemen as the community split several times, each recognizing a different Dai. Today, the Dawoodi Bohras, which constitute the majority of the Mustaali Ismāʿīlī accept Mohammed Burhanuddin as the 52nd Dāʿī al-Muṭlaq. The Dawoodi Bohras are based in India, along with the Alawi Bohra. The Sulaimani Bohra however still are in primarily Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

In recent years, there has been a rapprochement between the Sulaimani Mustaali and the Dawoodi Mustaali.

The Bohra are noted to be the more traditional of the three main groups of Ismāʿīlī, maintaining rituals such as prayer and fasting more consistently with the practices of other Shīˤa sects. It is often said they resemble Sunni Islam even more than Twelvers do, though this would hold true for matters of the exterior (zahir) only, with little bearing on doctrinal differences.

Dawoodi Bohra

The Dawoodi Bohras are a very closely-knit community who seek advice from the Dai on spiritual and temporal matters.

Dawoodi Bohras is essentially and traditionally Fatimid and is headed by the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq, who is appointed by his predecessor in office. The Dāˤī al-Mutlaq appoints two others to the subsidiary ranks of māzūn (Arabic Maʾḏūn مأذون) "licentiate" and Mukāsir (Arabic مكاسر). These positions are followed by the rank of ra'sul hudood, bhaisaheb, miya-saheb, shaikh-saheb and mulla-saheb, which are held by several of Bohras. The 'Aamil or Saheb-e Raza who is granted the permission to perform the religious ceremonies of the believers by the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq and also leads the local congregation in religious, social and community affairs, is sent to each town where a sizable population of believers exists. Such towns normally have a masjid (commonly known as mosque) and an adjoining jamaa'at-khaana (assembly hall) where socio-religious functions are held. The local organizations which manage these properties and administer the social and religious activities of the local Bohras report directly to the central administration of the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq.

While the majority of Dawoodi Bohras have traditionally been traders, it is becoming increasingly common for them to become professionals. Some choose to become Doctors, consultants or analysts as well as a large contingent of medical professionals. Dawoodi Bohras are encouraged to educate themselves in both religious and secular knowledge, and as a result, the number of professionals in the community is rapidly increasing. Dawoodi Bohras believe that the education of women is equally important to that of men, and many Dawoodi Bohra women choose to enter the workforce. Al Jamea tus Saifiyah (The Arabic Academy) in Surat and Karachi is a sign to the educational importance in the Dawoodi community. The Academy has an advanced curriculum which encompasses religious and secular education for both men and women.

Today there are approximately one million Dawoodi Bohras. The majority of these reside in India and Pakistan, but there is also a significant diaspora resident in the Middle East, East Africa, Europe, North America and the Far East.

The ordinary Bohra is highly conscious of his identity and this is especially demonstrated at religious and traditional occasions by the appearance and attire of the participants. Dawoodi Bohra men wear a traditional white three piece outfit, plus a white and gold cap (called a topi), and women wear the rida, a distinctive form of the commonly known burqa which is distinguished from other forms of the veil due to it often being in color and decorated with patterns and lace.

Besides speaking the local languages, the Dawoodis have their own language called Lisānu l-Dāˤwat "Tongue of the Dāˤwat". This is written in Arabic script but is derived from Urdu, Gujarati and Arabic and Persian.

Sulaimani Bohra

Founded in 1592, they are mostly concentrated in Yemen, but are today also found in Pakistan and India. The denomination is named after its 27th Daˤī, (Sulayman ibn Hassan).

The total number of Sulaimanis currently are around 300,000, mainly living in the eastern district of Haraz in the North west of Yemen and in Najaran, Saudi Arabia. Beside the Banu Yam of Najaran, the Sulaimanis are in Haraz, among the inhabitants of the Jabal Maghariba and in Hawzan, Lahab and Attara, as well as in the district of Hamdan and in the vicinity of Yarim.

In India there are between 3000-5000 Sulaimanis living mainly in Baroda, Hyderabad, Mumbai and Surat. In Pakistan there is a well established Sulaimani community in Sind, some five to six thousand Sulaimanis live in rural areas of Sind, these Ismāʿīlī Sulaimani communities are in Sind from the time of Fatimid Ismāʿīlī Muizz li din Allah when he sent his Dais to Sind.

There are also some 900-1000 Sulaimanis mainly from Indian Sub-continent scattered around the World, in the Persian Gulf States, USA, Canada, Thailand, Australia, Japan and UK.

Alavi Bohra

While lesser known and smallest in number, Alavi Bohras accept as the 44th dāʿī al-muṭlaq, Abu Haatim Taiyeb Ziyauddin Saheb. They are mostly concentrated in India.

The Alavi Bohra community has its headquarters at Baroda City, Gujarat, India. The 44th Dāˤī al-Mutlaq, Taiyeb Ziyauddin Saheb, is the head of the community. The religious hierarchy of the Alavi Bohras is essentially and traditionally Fatimid and is headed by the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq, who is appointed by his predecessor in office. The Dāˤī al-Mutlaq appoints two others to the subsidiary ranks of māzūn (Arabic Ma'ðūn مأذون)"licentiate" and Mukāsir (Arabic مكاسر). These positions are followed by the rank of ra'sul hudood, bhaisaheb, miya-saheb, shaikh-saheb and mulla-saheb, which are held by several of Bohras. The 'Aamil or Saheb-e Raza who is granted the permission to perform the religious ceremonies of the believers by the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq and also leads the local congregation in religious, social and community affairs, is sent to each town where a sizable population of believers exists. Such towns normally have a mosque and an adjoining jamaa'at-khaana (assembly hall) where socio-religious functions are held. The local organizations which manage these properties and administer the social and religious activities of the local Bohras report directly to the central administration of the Dāˤī al-Mutlaq.

Hebtiahs Bohra

The Hebtiahs Bohra are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shi'a Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 39th Da'i al-Mutlaq in 1754.[citation needed]

Atba-i-Malak

The Abta-i Malak jamaat (community) are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shi'a Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 46th Da'i al-Mutlaq, under the leadership of Abdul Hussain Jivaji. They have further split into two more branches, the Atba-i-Malak Badra and Atba-i-Malak Vakil.[35]

Druze

While on one view there is a historical nexus between the Druze and Ismāʿīlīs, any such links are purely historical and do not entail any modern similarities, given that one of the Druze's central tenets is trans-migration of the soul (reincarnation) as well as other contrasting beliefs with Ismāʿīlīsm and Islam. Druze is an offshoot of Ismailism. Many historical links do trace back to Syria and particularly Masyaf.

Extinct Branches

Hafizi

This branch held that whoever the political ruler of the Fatimid Empire was, was also the Imam of the faith. This branch died with the Fatimid Empire.

Seveners

A branch of the Ismāʿīlī known as the Sabaʿiyyīn "Seveners" hold that Ismāʿīl's son, Muhammad, was the seventh and final Ismāʿīlī, who is said to be in the Occultation.[15] However, most scholars believe this group is either extremely small or totally non-existent today.

Ainsarii

The Ainsarii were a sect of the Ismailis who survived the destruction of the stronghold of Alamut. An Ismaili sect of the Assassins, who continued to exist after the stronghold of that society was destroyed.

Inclusion in Amman Message and Islamic Ummah

Although Ismāʿīlīsm is traditionally rejected by many Sunni and Shī‘ite Muslim scholars as a heretical sect, the Amman Message, which was issued on November 9, 2004 (27th of Ramadan 1425 AH) by King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein of Jordan, called for tolerance and unity in the Muslim world. Subsequently, a three-point dossier was issued by 200 Muslim academics from over 50 countries, focusing on issues of: defining who a Muslim is; and principles related to delivering religious edicts. As per the recognition via Islamic theology, Ismāʿīlīsm was included as an alternative Madh'hab.[36] In the Amman Message Ismāʿīlīs are referred to as Jafari, a term that denotes both Ismāʿīlī and Twelvers due to their Imamate descending from Imam Jafar as-Sadiq.[37][38][39]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Religion of My Ancestors". Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ "Shaykh Ahmad al-Ahsa'i". Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.76

- ^ "Congressional Human Rights Caucus Testimony - NAJRAN, The Untold Story". Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ "News Summary: China; Latvia". Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 0-7486-0687-4.

- ^ ibn Abu talib, Ali. Najul'Balagha.

- ^ "Imam Ali". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "The Kharijites and their impact on Contemporary Islam". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "Ali bin Abu Talib". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "Hussain bin Ali". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "Imam Baqir". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ S.H. Nasr (2006), Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy, State University of New York Press, p. 146

- ^ "Imam Ja'far b. Muhammad al Sadi'q". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ a b c d Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʿīlīs: Their history and doctrines. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-521-42974-9. Cite error: The named reference "DaftaryIsmailis1990p104" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 36–50. ISBN 0-7486-0687-4.

- ^ Abbas Amanat, Magnus Thorkell. Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse. p. 123.

- ^ Delia Cortese, Simonetta Calderini. Women and the Fatimids in the World of Islam. p. 26.

- ^ Abbas Amanat, Magnus Thorkell. Imagining the End: Visions of Apocalypse. p. 123.

- ^ Abū Yaʻqūb Al-Sijistānī. Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism. p. 161.

- ^ by Yuri Stoyanov. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy.

- ^ Gustave Edmund Von Grunebaum. Classical Islam: A History, 600-1258. p. 113.

- ^ Yuri Stoyanov. The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy.

- ^ "Qarmatiyyah". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ "MUHAMMAD AL-MAHDI (386-411/996-1021)". Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ^ "al-Hakim bi Amr Allah: Fatimid Caliph of Egypt". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 106–108. ISBN 0-7486-0687-4.

- ^ a b c d e Campbell, Anthony (2004). The Assassins of Alamut. p. 84.

- ^ Maalouf, Amin (1998). Samarkand.

- ^ a b "Isma'ilism". Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Halm, Heinz (1988). Die Schia. Darmstadt, Germany: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. pp. 202–204. ISBN 3-534-03136-9.

- ^ Kitab al-Kafi.

- ^ "The Ismaili: His Highness the Aga Khan". Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ a b Daftary, Farhad (1998). A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 196–199. ISBN 0-7486-0687-4.

- ^ http://www.islamicvoice.com/september.98/features.htm

- ^ http://ammanmessage.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=22&Itemid=34

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=xX5mAAAAMAAJ&q=Jafari+shi%27a&dq=Jafari+shi%27a&lr=&ei=H-yaSrerJJ_4lATVpMWLAQ

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=Azo-1-8mm1cC&pg=PA89&dq=Jafari+shi%27a&lr=&ei=p-qaSvKxGYbYlQSFpqyaAQ#v=onepage&q=Jafari%20shi'a&f=false

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?id=6VeCWQfVNjkC&pg=PA271&dq=Jafari+Ismaili&lr=&ei=Z-maSv22CJv8lATJ6JB5#v=onepage&q=Jafari%20Ismaili&f=false