Charles Sumner: Difference between revisions

keep focus on Sumner |

Seikonekoala (talk | contribs) m →Antebellum career and attack by Preston Brooks: copyedit |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

Sumner was helped to a room outside and was taken home, where he said, "I could not believe that a thing like this was possible." He did not attend the Senate for the next three years, recovering from the attack; Sumner suffered from nightmares, headaches, and [[post-traumatic stress disorder|post-traumatic shock]] in addition to the [[Head injury|head trauma]]. The Massachusetts General Court reelected him, in the belief that in the Senate chamber his vacant chair was the most eloquent pleader for [[free speech]] and resistance to slavery. Sumner's chair was later purchased by [[Bates College]], an abolitionist leaning school with which Sumner was involved. |

Sumner was helped to a room outside and was taken home, where he said, "I could not believe that a thing like this was possible." He did not attend the Senate for the next three years, recovering from the attack; Sumner suffered from nightmares, headaches, and [[post-traumatic stress disorder|post-traumatic shock]] in addition to the [[Head injury|head trauma]]. The Massachusetts General Court reelected him, in the belief that in the Senate chamber his vacant chair was the most eloquent pleader for [[free speech]] and resistance to slavery. Sumner's chair was later purchased by [[Bates College]], an abolitionist leaning school with which Sumner was involved. |

||

Brooks was arrested but released on $500 bail and later fined $300. An effort to expel him from the House on [[July 14]] failed to reach the necessary two-thirds majority, because all Southern representatives except one voted against it. He was only [[Censure|censured]] but [[resignation|resigned]] anyway. Immediately before his resignation he gave a speech, "On the Sumner Assault," in which he defended the attack and vilified Sumner. Brooks was hailed throughout the South and reelected immediately after resignation |

Brooks was arrested but released on $500 bail and later fined $300. An effort to expel him from the House on [[July 14]] failed to reach the necessary two-thirds majority, because all Southern representatives except one voted against it. He was only [[Censure|censured]] but [[resignation|resigned]] anyway. Immediately before his resignation he gave a speech, "On the Sumner Assault," in which he defended the attack and vilified Sumner. Brooks was hailed throughout the South and reelected immediately after resignation with almost no opposition. |

||

The act revealed the increasing polarization of the Union in the years before the [[American Civil War]], as Sumner became a hero in Massachusetts and Brooks a hero in South Carolina. It was also noted that Brooks did not challenge Sumner to a [[duel]], because that was the method of solving disputes between [[Gentleman|gentlemen]]; Brooks regarded Sumner as his social inferior. Northerners were outraged, with the editor of the ''[[New York Post|New York Evening Post]]'', William Cullen Bryant, writing: |

The act revealed the increasing polarization of the Union in the years before the [[American Civil War]], as Sumner became a hero in Massachusetts and Brooks a hero in South Carolina. It was also noted that Brooks did not challenge Sumner to a [[duel]], because that was the method of solving disputes between [[Gentleman|gentlemen]]; Brooks regarded Sumner as his social inferior. Northerners were outraged, with the editor of the ''[[New York Post|New York Evening Post]]'', William Cullen Bryant, writing: |

||

Revision as of 01:58, 19 January 2006

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811–March 11, 1874) was an American politician and statesman from the U.S. state of Massachusetts. A noted lawyer and orator, Sumner was at various times a Whig, a Free Soiler, and a Republican. He devoted his enormous energies to the destruction of what he considered the Slave Power, that is the conspiracy of slave owners to seize control of the federal government and block the progress of liberty. He served in the U.S. Senate for 23 years, from 1851 to his death, gaining fame as one of the most prominent abolitionists, Radical Republicans, and Liberal Republicans.

Early life, education, and law career

Sumner was born in Boston on January 6, 1811. He attended the Boston Latin School. He graduated in 1830 from Harvard College (where he lived in Hollis Hall), and in 1834 from Harvard Law School. At Harvard Law School, Sumner studied jurisprudence with his friend Joseph Story.

In 1834, Sumner was admitted to the bar at the age of 23, and entered private practice in Boston, where he partnered with George Stillman Hillard. A visit to Washington, D.C. sometime around this period filled him with loathing for politics as a career, and he returned to Boston resolved to devote himself to the practice of law. During this time, he contributed to the quarterly "American Jurist" and edited Story's court decisions as well as some law texts. From 1836 to 1837, Sumner lectured at Harvard Law School.

Travels in Europe

From 1837 to 1840, Sumner traveled extensively in Europe. There he learned fluent French, German and Italian, with a command of foreign languages equalled by no American then in public life. He met with many of the leading statesmen in Europe, and secured a deep insight into Continental law and government.

Sumner visited England in 1838, where his knowledge of literature, history, and law made him popular with leaders of thought. Henry Peter Brougham, 1st Baron Brougham and Vaux declared that he "had never met with any man of Sumner's age of such extensive legal knowledge and natural legal intellect." Not until many years after Sumner's death was any other American received so intimately into the British intellectual circles.

Beginning of political career

In 1840, at the age of 30, Sumner returned to Boston, resolved to settle down to the practice of law. But gradually he devoted less of his time to practice and more to lecturing at Harvard Law School, to editing court reports, and to contributing to law journals, especially on historical and biographical lines.

In his law practice he had disappointed himself and his friends, and he became despondent as to his future. It was at an Independence Day oration on "The True Grandeur of Nations," delivered in Boston on July 4, 1845, that was a turning point in Sumner's life. His oration was a tremendous arraignment of war, and an impassioned appeal for freedom and peace, and proved him a first-class orator.

He immediately became one of the most eagerly-sought orators in the North. His lofty themes and stately eloquence made a profound impression, especially upon young men; his platform presence was imposing (he stood six feet and four inches tall, with a massive frame). His voice was clear and of great power; his gestures unconventional and individual, but vigorous and impressive. His literary style was florid, with much detail, allusion, and quotation, often from the Bible as well as ancient Greece and Rome. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote that he delivered speeches "like a cannoneer ramming down cartridges," while Sumner himself said that "you might as well look for a joke in the Book of Revelations."

Sumner cooperated effectively with Horace Mann for the improvement of the system of public education in Massachusetts. Prison reform and oppossion to the Mexican-American War were strongly advocated for by Sumner. He viewed the war as imperialist aggression and was concerned that captured territories would expand slavery westward. In 1847, the vigor with which Sumner denounced a Boston congressman's vote in favor of the declaration of war aganist Mexico made him a leader of the "conscience Whigs," but he declined to accept their nomination for House of Representatives.

Sumner took an active part in the organizing of the Free Soil Party, in revolt at the Whigs' nomination of a slave-holding southerner for the presidency; and in 1848 was defeated as a candidate for the national House of Representatives. On December 4, 1849, Sumner unsuccessfully argued that segregated public schools were unconstitutional before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in Roberts v. Boston.

In 1851, control of the Massachusetts General Court was secured by the Democrats in coalition with the Free Soilers. However, the legislature deadlocked on who should succeed Daniel Webster (who had accepted Millard Fillmore's appointment as Secretary of State) in the U.S. Senate. After filling the state positions with Democrats, the Democrats refused to vote for Sumner (the Free Soilers' choice) and urged the selection of a less radical candidate. An impasse of more than three months ensued, finally resulting in the election of Sumner by a single vote on April 24.

Service in the Senate

Antebellum career and attack by Preston Brooks

Sumner took his seat in the Senate on December 1, 1851. For the first few sessions Sumner did not push for any of his controversial causes, but observed the workings of the Senate. On August 26, 1852, Sumner delivered, in spite of strenuous efforts to prevent it, his first major speech. Entitled "Freedom National; Slavery Sectional" (a popular abolitionist motto), Sumner attacked the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and called for its repeal.

The conventions of both the great parties had just affirmed the finality of every provision of the Compromise of 1850. Reckless of political expediency, Sumner moved that the Fugitive Slave Act be forthwith repealed; and for more than three hours he denounced it as a violation of the constitution, an affront to the public conscience, and an offense against the divine law. The speech provoked a storm of anger in the South, but the North was heartened to find at last a leader whose courage matched his conscience.

In 1856, during the Bloody Kansas crisis when "border ruffians" approached Lawrence, Kansas, Sumner denounced the Kansas-Nebraska Act in the "Crime against Kansas" speech on May 19 and May 20, two days before the sack of Lawrence. Sumner attacked the authors of the act, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Andrew Butler of South Carolina, comparing Douglas to Don Quixote and Sancho Panza.

The speech contained several mocking references to a speech impediment of Butler ("with incoherent phrases, discharged the loose expectoration of his speech, now upon her representative, and then upon her people") who had suffered a stroke causing the disability. Sumner said Douglas (who was present in the chamber) was "noise-some, squat, and nameless animal...not a proper model for an American senator," while he said Butler (who was not present) took "a mistress...who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean, the harlot, slavery." That is, Sumner said Butler was a pimp.

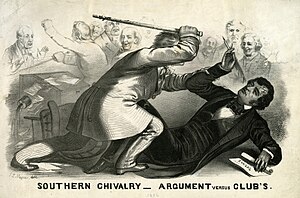

Two days later, on the afternoon of May 22, Preston Brooks, a congressman from South Carolina and Butler's nephew, confronted Sumner as he sat writing at his desk in the almost empty Senate chamber, attaching his postal frank to copies of his speech. Preston said "Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech twice over carefully. It is a libel on South Carolina, and Mr. Butler, who is a relative of mine—" As Sumner began to stand up, Brooks began beating Sumner on the head with a thick gutta-percha cane with a gold head. Sumner was trapped under the heavy desk (which was bolted to the floor), but Brooks continued to bash Sumner until he ripped the desk from the floor. By this time, Sumner was blinded by his own blood, and he staggered up the aisle and collapsed, lapsing into unconsciousness. Brooks continued to beat Sumner until he broke his cane, then quietly left the chamber.

Sumner was helped to a room outside and was taken home, where he said, "I could not believe that a thing like this was possible." He did not attend the Senate for the next three years, recovering from the attack; Sumner suffered from nightmares, headaches, and post-traumatic shock in addition to the head trauma. The Massachusetts General Court reelected him, in the belief that in the Senate chamber his vacant chair was the most eloquent pleader for free speech and resistance to slavery. Sumner's chair was later purchased by Bates College, an abolitionist leaning school with which Sumner was involved.

Brooks was arrested but released on $500 bail and later fined $300. An effort to expel him from the House on July 14 failed to reach the necessary two-thirds majority, because all Southern representatives except one voted against it. He was only censured but resigned anyway. Immediately before his resignation he gave a speech, "On the Sumner Assault," in which he defended the attack and vilified Sumner. Brooks was hailed throughout the South and reelected immediately after resignation with almost no opposition.

The act revealed the increasing polarization of the Union in the years before the American Civil War, as Sumner became a hero in Massachusetts and Brooks a hero in South Carolina. It was also noted that Brooks did not challenge Sumner to a duel, because that was the method of solving disputes between gentlemen; Brooks regarded Sumner as his social inferior. Northerners were outraged, with the editor of the New York Evening Post, William Cullen Bryant, writing:

- The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and wold stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder.

- Has it come to this, that we must speak with bated breath in the presence of our Southern masters?... Are we to be chastised as they chastise their slaves? Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them?"

Conversely, the act was praised by Southern newspapers; the Richmond Enquirer wrote an editorial that said Sumner should be caned "every morning," praising the attack as "good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequences" and denounced "these vulgar abolitionists in the Senate" who "have been suffered to run too long without collars. They must be lashed into submission."

American Civil War

After years of medically assisted recuperation Sumner returned to the Senate in 1859. He delivered a speech entitled "The Barbarism of Slavery" in the months leading up to the 1860 presidential election. In the critical months following the election of Abraham Lincoln election, Sumner was an unyielding foe to every scheme of compromise with the Confederate States of America. After the withdrawal of the Southern senators, Sumner was made chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations on March 8, 1861, a position for which he was well-qualified for because of his years of acquaintance with European politicians and statesmen. While the war was in progress, Sumner's letters from Richard Cobden and John Bright, from William Ewart Gladstone and the George Douglas Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll, were read by Sumner at Lincoln's request to the Cabinet, and formed a chief source of knowledge on the political situation in Britain.

In the turmoil over the Trent affair, it was Sumner's word that convinced Lincoln that James M. Mason and John Slidell must be given up. Again and again Sumner used the power incident to his chairmanship to block action which threatened to embroil the United States in war with England and France. Sumner openly and boldly advocated the policy of emancipation. Lincoln described Sumner as "my idea of a bishop," and used to consult him as an embodiment of the conscience of the American people.

Sumner was a longtime enemy of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, who attacked his decision in the Dred Scott v. Sandford. In 1865, Congress rejected a proposal to commission a bust of Taney to be displayed with the four Chief Justices who preceded him. Sumner said:

- I speak what cannot be denied when I declare that the opinion of the Chief Justice in the case of Dred Scott was more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of courts. Judicial baseness reached its lowest point on that occasion. You have not forgotten that terrible decision where a most unrighteous judgment was sustained by a falsification of history. Of course, the Constitution of the United States and every principle of Liberty was falsified, but historical truth was falsified also..."

Upon hearing the news of Taney's passing, Sumner wrote Lincoln in celebration declaring that "Providence has given us a victory" in Taney's death.

The Civil War had hardly begun when Sumner put forward his theory of reconstruction, that the South had by its own act become felo de se, committing state suicide via secession, and that they be treated as conquered territory that had had never been states. He resented the loose Reconstruction policy taken by Lincoln, and later by Andrew Johnson, as an encroachment upon the powers of Congress. Throughout the war Sumner had constituted himself the special champion of blacks, being the most vigorous advocate of emancipation, of enlisting the blacks in the Union army, and of the establishment of the Freedmen's Bureau. A friend of Samuel Gridley Howe, he was also a guiding force for the American Freedmen's Inquiry Commission. Sumner was one of the most prominent advocates for suffrage, along with free homesteads and free public schools for blacks.

Reconstruction years and death

Sumner was strongly opposed to the Reconstruction policy of Johnson, believing it to be far to generous to the South. Johnson was impeached by the House, but the Senate failed to convict him and thus remove him from office by a single vote.

Ulysses S. Grant became a bitter opponent of Sumner in 1870 when the president mistakenly thought that he had secured his support for the annexation of San Domingo.

Sumner had always prized highly his popularity in England, but he unhesitatingly sacrificed it in taking his stand as to the adjustment of claims against England for breaches of neutrality during the war. Sumner laid great stress upon "national claims." He held that England's according the rights of belligerents to the Confederacy had doubled the duration of the war, entailing inestimable loss. He therefore insisted that England should be required not merely to pay damages for the havoc wreaked by the CSS Alabama and other cruisers fitted out for Confederate service in her ports, but that, for "that other damage, immense and infinite, caused by the prolongation of the war," the withdrawal of the British flag from this hemisphere could "not be abandoned as a condition or preliminary of such a settlement as is now proposed." (At the Geneva arbitration conference these "national claims" were abandoned.) Under pressure from the president, on the ground that Sumner was no longer on speaking terms with the secretary of state, he was deposed on March 10, 1871, from the chairmanship of the Committee on Foreign Relations, in which he had served with great distinction and effectiveness throughout the critical years since 1861. Whether the chief cause of this humiliation was Grant's vindictiveness at Sumner's opposition to his San Domingo project or a genuine fear that the impossible demand, which he insisted should be made upon England, would wreck the prospect of a speedy and honourable adjustment with that country, cannot be determined. In any case it was a cruel blow to a man already broken by racking illness and domestic sorrows. Sumner's last years were further saddened by the misconstruction put upon one of his most magnanimous acts. In 1872, he introduced in the Senate a resolution providing that the names of battles with fellow citizens should not be placed on the regimental colours of the United States. The Massachusetts legislature denounced this battle-flag resolution as "an insult to the loyal soldiery of the nation" and as "meeting the unqualified condemnation of the people of the Commonwealth." For more than a year all efforts– headed by the poet John Greenleaf Whittier– to rescind that censure were without avail, but early in 1874 it was annulled. On the 10th of March, against the advice of his physician, Sumner went to the Senate– it was the day on which his colleague was to present the rescinding resolution. With those grateful words of vindication from Massachusetts in his ears Sumner left the Senate chamber for the last time. That night he was stricken with an acute attack of angina pectoris, and on the following day he died. He lied in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda and was buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery.

Sumner was the scholar in politics. He could never be induced to suit his action to the political expediency of the moment. "The slave of principles, I call no party master," was the proud avowal with which he began his service in the Senate. For the tasks of Reconstruction he showed little aptitude. He was less a builder than a prophet. His was the first clear program proposed in Congress for the reform of the civil service. It was his dauntless courage in denouncing compromise, in demanding the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act, and in insisting upon emancipation, that made him the chief initiating force in the struggle that put an end to slavery.

References

- David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Coming of the Civil War (1960), the standard biography

- David Donald, Charles Sumner and the Rights of Man (1970), the standard biography

- Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (1970), history of ideas

- Moorfield Storey, Charles Sumner (1900)

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)