AgustaWestland AW101: Difference between revisions

Miker32159 (talk | contribs) |

Miker32159 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

To alleviate a shortfall in operational helicopters the British Ministry of Defence acquired six DMRH AW101s from Denmark in 2007. These were assigned to the RAF with the designation '''Merlin HC3A'''. As part of the deal, the UK Ministry of Defence ordered six new-build replacements for the Royal Danish Air Force. In December 2007, a second Merlin squadron, [[No. 78 Squadron RAF|No. 78 Squadron]] was formed at Benson.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.raf.mod.uk/news/index.cfm?storyid=A64EDF95-1143-EC82-2EBC003A8CAFA24D |title = 78 Squadron Operational |publisher = Royal Air Force |date = 3 December 2007}}</ref> Five Merlin Mk3s are operating in Afghanistan in 2010; their initial deployment was criticised as they allegedly lack Kevlar armour,<ref>{{cite web |url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8182649.stm |title = MoD denies Merlin 'unsafe' claims |publisher = BBC News |date = 4 August 2009}}</ref> the aircraft are now fully fitted with ballistic protection armour.{{Citation needed|date=February 2010}} |

To alleviate a shortfall in operational helicopters the British Ministry of Defence acquired six DMRH AW101s from Denmark in 2007. These were assigned to the RAF with the designation '''Merlin HC3A'''. As part of the deal, the UK Ministry of Defence ordered six new-build replacements for the Royal Danish Air Force. In December 2007, a second Merlin squadron, [[No. 78 Squadron RAF|No. 78 Squadron]] was formed at Benson.<ref>{{cite web |url = http://www.raf.mod.uk/news/index.cfm?storyid=A64EDF95-1143-EC82-2EBC003A8CAFA24D |title = 78 Squadron Operational |publisher = Royal Air Force |date = 3 December 2007}}</ref> Five Merlin Mk3s are operating in Afghanistan in 2010; their initial deployment was criticised as they allegedly lack Kevlar armour,<ref>{{cite web |url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/8182649.stm |title = MoD denies Merlin 'unsafe' claims |publisher = BBC News |date = 4 August 2009}}</ref> the aircraft are now fully fitted with ballistic protection armour.{{Citation needed|date=February 2010}} |

||

It has been announced that the RAF will transfer its Merlins to the Royal Navy (specifically the [[Commando Helicopter Force]]) and receive [[Boeing Chinook (UK variants)|Chinook HC2]]s as replacements |

It has been announced that the RAF will transfer its Merlins to the Royal Navy (specifically the [[Commando Helicopter Force]]) and receive [[Boeing Chinook (UK variants)|Chinook HC2]]s as replacements. |

||

===Italian Navy=== |

===Italian Navy=== |

||

Revision as of 10:40, 2 May 2010

| AW101 (EH101) Merlin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Royal Air Force Merlin HC3 | |

| Role | ASW & medium-lift transport / Utility helicopter |

| Manufacturer | AgustaWestland |

| First flight | 9 October 1987 |

| Introduction | 2000 |

| Status | Active service |

| Primary users | Royal Navy Royal Air Force Italian Navy Portuguese Air Force |

| Produced | 1990s-present |

| Variants | CH-149 Cormorant VH-71 Kestrel |

The AgustaWestland AW101 (EH101 until June 2007) is a medium-lift helicopter for military applications but also marketed for civil use. The helicopter was developed as a joint venture between Westland Helicopters in the UK and Agusta in Italy (now merged as AgustaWestland). The aircraft is manufactured at the AgustaWestland factories in Yeovil, England and Vergiate, Italy. The name Merlin is used for AW101s in the British, Danish and Portuguese militaries.[1][2]

Development

In Spring 1977, the UK Ministry of Defence issued a requirement for an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter to replace the Royal Navy's Westland Sea Kings. Westland responded with a design designated the WG.34 that was then approved for development.[3] Meanwhile, the Marina Militare (Italian Navy) was also seeking a replacement for its (Agusta-built) Sea Kings, leading Agusta to discussions with Westland about the possibility of a joint development.[4] This culminated in the joint venture being finalised in November 1979 and a new London-based company, EH Industries Limited (EHI), being formed in June the following year to manage the project.

As the design studies progressed, EHI became aware of a broader market for an aircraft with the same capabilities as those required by the British and Italian navies. On 12 June 1981, the UK confirmed their participation, with an initial budget of £20 billion to develop nine pre-series examples.[5] A major agreement securing funding for the development of the EH-101 program was signed by both the British and Italian governments in 1984.[6] At the 1985 Paris Air Show at Le Bourget, Agusta showed a mock-up of a utility version of the new helicopter, leading to a more generalised design that could be customised. After a lengthy development, the first prototype flew on 9 October 1987.[7]

In 1989 demand for the EH-101 was uncertain, the American Blackhawk was providing competition with potential export customers, and neither Britain or Italy had placed production orders yet.[8] The Canadian government had expressed considerable interest in 1991 in acquiring up to 43 EH-101s to replace their own aging naval helicopters;[9] however with the end of the Cold War they were branded as excessive by several politicians and the acquisition was aborted in 1996.[10][11] Britain maintained its commitment to the project, ordering 22 EH-101 helicopters in February 1995;[12] Italy also pressed ahead with its order for 16 EH-101s in October 1995.[13]

The first group of production EH-101s for the RAF began arriving in 1997.[14] In 2002 Westland made an unsolicited and unsuccessful offer to provide the MoD with an enhanced version of the Merlin to meet the UK's demand for lift capability.[15] Westland and Agusta merged together to form AgustaWestland International Limited in July 2000,[16][17] closing down EHI as a separate entity shortly afterwards. Consequently in June 2007 the EH101 was re-branded as the AW101.[18]

Design

Overview

The AW101 Merlin is well known for its extensive use of composite materials.[19] The modular aluminium-lithium alloy fuselage structure is damage and crash resistant, with multiple primary and secondary load paths. Active vibration control of the structural response (ACSR) uses a vibration-canceling technique to reduce the stress on the airframe. The AW101 is rated to operate in temperatures ranging from -40 to +50 °C. High flotation tyres permit operation from soft or rough terrain. The main rotor blades are a derivative of the BERP rotor blade design, which improves the aerodynamic efficiency at the blade tips, as well as reducing the blade's noise signature.[20]

The cockpit is fitted with armoured seats for the crew, and can withstand an impact velocity of over 10 m/s. Dual flight controls are provided, though the EH-101 can be flown by a single person. The pilot's instrument displays include six full colour high-definition screens and an optional mission display.[21] A digital map and Forward-Looking Infrared system display can also be installed.

Propulsion

The military version of the AW101 is powered by either three Rolls-Royce/Turbomeca RTM322 turboshafts used by the UK, Japan, Denmark and Portugal; or three 1,491 kW General Electric CT7-6 turboshafts in Italy, Canada, and Japan. The Rolls-Royce RTM322 engine was specifically designed for the AW101,[22] and was later used other helicopters such as the WAH-64 Apache.[23] Engine inlet particle separator systems provide protection when operating in sandy environments. Each engine is supplied by a separate 1,074 litre self-sealing fuel tank using dual booster pumps. A fourth tank acts as a reservoir supply, topping up the main tanks during flight; while a fifth transfer tank can be added to increase range, as can airborne refuelling. The engines power an 18.59 metre diameter five-bladed main rotor. The rotor blades are constructed from carbon/glass with nomex honeycomb and rohacell foam, edged with titanium alloy. Computer control of the engines via the aircraft EECU's (electronic engine control unit) allows the AW101 to hover reliably in winds of over 80 km/h.

Weapon and defensive systems

A chin FLIR is fitted to some variants.[24] The AW101 (excluding the ASM MK1) is equipped with Chaff and flare dispensers, directed infrared countermeasures (infrared jammers), ESM (electronic support measures, in the form of RF [radio frequency] heads), and a laser detection and warning system.[25]

It has two hard points for weapon carriers, on which the HM Mk1 model can carry four Sting Ray torpedoes or Mk 11 Mod 3 depth charges, though at present cannot use the Sea Skua missile. The Mk1, Mk3 and 3a variants can mount General Purpose Machine Guns (GPMGs) in up to 5 locations in the main cabin pointing out of door and window apertures.

Cargo systems

The AW101's fuselage has a volume of 31.91 m3 and the cargo compartment is 6.5 m in length, 2.3 m wide and 1.91 m high. The military version of the AW101 can accommodate up to 24 seated or 45 standing combat troops and their equipment. Alternative loads include a medical team and 16 stretchers, and cargo pallets.[26] The cabin floor and rear ramp are fitted with flush tie-down points, a semi-automatic cargo release unit (SACRU). The ramp (1.91x2.3 m) can take a 3,050 kg load, allowing it to carry vehicles such as Land Rovers.[27] A cargo hook under the fuselage can carry external loads of 5,440 kg via the use of a SACRU.[28] A rescue hoist and a hover trim controller are fitted at the cargo door.

Avionics

The navigation system includes a GPS and inertial navigation system, VHF Omnidirectional Radio range (VOR) instrument landing system (ILS), tactical air navigation (TACAN) and automatic direction finding. The MK1 and MK3 are equipped with a DVS (Doppler velocity system) for when the exclusive use of the conventional pitot pressure instruments might be unreliable for gauging accurate airspeed. The AW101 is equipped with helicopter management, avionics and mission systems linked by two 1553B multiplex and ARINC 429 databuses. A Smiths Industries OMI 20 SEP automatic flight control system provides dual redundant digital control, giving autostabilisation and four-axis auto-pilot operation.

Operational history

British Royal Navy

The RN's final order was for 44 ASW machines, originally designated Merlin HAS.1 but soon changed to Merlin HM1. The first fully operational Merlin was delivered on 17 May 1997, entering service on 2 June 2000. All aircraft were delivered by the end of 2002, and are operated by four Fleet Air Arm squadrons, all based at RNAS Culdrose in Cornwall: 814 NAS, 820 NAS, 824 NAS and 829 NAS. 700 NAS was the Merlin Operational Evaluation Unit from 2000 to 2008.

In March 2004, RN Merlins were grounded following an incident at RNAS Culdrose when the tail rotor failed on one of them. Investigations revealed that this was due to tail rotor hub manufacturing defects.[29] Flights resumed the following year.

The Merlin HM1 has been cleared to operate from the Royal Navy's aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, Type 23 frigates and a number of RFA vessels including the Fort Victoria Class. It is also intended to equip the forthcoming Type 45 destroyers. A Capability Sustainment Programme is currently in place to upgrade 30 aircraft to the Merlin HM2 standard. This will include a new mission system and digital cockpit. It had been planned to include the remaining 8 airframes but this has now been dropped for financial reasons while alternative roles were sought for these aircraft.[30]

The UK had long considered the Merlin as a replacement for the Sea King ASaC7 in the Airborne Early Warning (AEW) role.[31] On 15 December 2009, the future helicopter plans were announced. The RAF Merlin HC3 and HC3As will be moved to the Commando Helicopter Force replacing 'junglie' Sea King Commando helicopter, these helicopters being replaced with Chinooks in RAF service. The eight spare airframes will be refitted with equipment from the Sea King ASaC7. Sea King will also be replaced in the SAR role by a PFI deal, resulting in the retirement of Sea King, leaving the Navy operating Lynx Wildcat and Merlin, the RAF operating Chinooks, and Army operating Lynx Wildcat and Apache.[32] The Lynx helicopter has been seen as a useful compliment to the newer Merlins, however it had been mooted in 1995 than phasing out Lynx for an all-Merlin fleet in maritime use would be plausible.[33]

Royal Navy Merlins have seen action in the Caribbean, on counter-narcotics and hurricane support duties. They have also been active in Iraq, providing support to British and coalition troops on the ground, as well as maritime security duties in the North Persian Gulf.

British Royal Air Force

RAF ordered 22 transport helicopters designated Merlin HC3, the first of which entered service with No. 28 Squadron RAF, based at RAF Benson, in January 2001. The type is equipped with extended-range fuel tanks and is capable of air-to-air refueling; however, due to the lack of a suitable UK tanker aircraft, this capability has not been cleared for use. It also differs from the Royal Navy version by having double-wheel main landing gear, whereas the RN version only has a single wheel on each of the main gears.

Depth maintenance of Merlin HC3 is carried out at the Merlin Depth Maintenance Facility at RNAS Culdrose.[34] The first operational deployment was to the Balkans in early 2003. They were deployed to southern Iraq as part of Operation Telic until July 2009 when British Forces withdrew from Iraq.

To alleviate a shortfall in operational helicopters the British Ministry of Defence acquired six DMRH AW101s from Denmark in 2007. These were assigned to the RAF with the designation Merlin HC3A. As part of the deal, the UK Ministry of Defence ordered six new-build replacements for the Royal Danish Air Force. In December 2007, a second Merlin squadron, No. 78 Squadron was formed at Benson.[35] Five Merlin Mk3s are operating in Afghanistan in 2010; their initial deployment was criticised as they allegedly lack Kevlar armour,[36] the aircraft are now fully fitted with ballistic protection armour.[citation needed]

It has been announced that the RAF will transfer its Merlins to the Royal Navy (specifically the Commando Helicopter Force) and receive Chinook HC2s as replacements.

Italian Navy

In 1997, the Italian government ordered 20 EH101 helicopters with four options for the Italian Navy in the following variants:[37]

- 9 (+1) anti-surface and anti-submarine (ASW)

- 4 (+2) early-warning (AEW)

- 4 utility aircraft

- 4 ASH (Amphibious Support Helicopter)

The first Italian Navy production helicopter (MM81480) was first flown on 4 October 1999 and was officially presented to the press on 6 December 1999 at the Agusta factory. Deliveries to the Italian Navy started at the beginning of 2001 and were completed by 2006. Italian EH101s operate from a variety of ships, including aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships. The 9th ASW helicopter was delivered on August 2009.

The AW-101 was chosen for CSAR program, 12 + 3 option, of Aeronautica Militare (Air Force) for replacement of HH-3F.

Royal Danish Air Force

In 2001, the Royal Danish Air Force announced the purchase of eight EH101s for SAR duties and six tactical troop transports.[38] The last of the 14 EH101s was delivered 1 March 2007 and the first SAR EH101s became operational in late April 2007. The Danish Mk 512s have a MTOW of 15,600 kg.

In 2007, the British Ministry of Defence acquired the six troop transport EH101s from Denmark to alleviate a shortfall in British operational helicopters. In exchange, the British have ordered six new-build helicopters from AgustaWestland as replacements for the Royal Danish Air Force.

On 28 January 2008, one Danish AW101 broke the drive shaft from one engine to the gear box and made an emergency landing at Billund Airport. Following this incident the Danish fleet was grounded as a safety precaution. The incident provoked national debate about the future of the EH101 in Danish service and whether it made sense to acquire different helicopters, since the EH101 had very low availability of roughly 30% due to mechanical issues. AgustaWestland in turn blamed the Danes for ordering spare parts very late and not keeping enough staff to properly service the helicopters.[39] In April 2008, RDAF reported considerable improvements in operational availability of over 50%, citing improved service from AW (speedy delivery of spare parts) and increased proficiency of ground crews as responsible.[citation needed]

Portuguese Air Force

The Portuguese Air Force has operated Merlins since 24 February 2005, in transport, search and rescue, combat search and rescue, fisheries surveillance and maritime surveillance missions. The 12 aircraft, in three versions, gradually replaced the Aérospatiale Puma in those roles. Portuguese Merlins are painted in a tactical green and brown camouflage.

The main role of the Portuguese AW101 is search and rescue in Portugal's maritime zone. EH-101s are on constant alert at three bases: Montijo (near Lisbon), Lajes Field, Azores and Porto Santo Island.

Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force

The Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ordered 14 aircraft in 2003 to use in both the AMCM (Airborne Mine Counter-Measures) and transport roles.[40] The AW101 was modified by Kawasaki Heavy Industries, and the Japan Defense Agency designated the model MCH-101. The characteristic could fold rotor and tail automatically, carried Active anti-vibration system.[41]

AgustaWestland, the Kawasaki and the Marubeni entered into a general agreement in 2002. Kawasaki began assembly of the CH-101 and the MCH-101 in 2003. The MEXT uses CH-101 for the Antarctic transportation. Kawasaki began license production of the Rolls-Royce/Turbomeca RTM322 turboshaft engines in 2005.[42] The first MCH-101 was delivered to the Self-Defense Force on 3 March 2006.[40][41]

The MCH-101 and CH-101 will replace the MH-53E (S-80-M-1) for AMCM, and the Sikorsky S-61 in a support role for Japanese Antarctic observations.[43] AgustaWestland received an order for 14 MCH-101 and CH-101, and remaining 12 aircraft will be assembled by Kawasaki in Japan.[44] The Marubeni agreement with AgustaWestland established a Spare Parts Depot in Japan for support the MCH-101 and CH-101 fleet.[45]

Other military customers

There has been a considerable demand for the AW-101; which has kept a continuous queue of customers for over five years.[46]

Norway has expressed an interest in the AW101 as a candidate for the Norwegian All Weather Search and Rescue Helicopter (NAWSARH) programme, that is planned to replace the Westland Sea King Mk.43B of the Royal Norwegian Air Force in 2015.[47] The other candidates for the NAWSARH contract of 10-12 helicopters are Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, Eurocopter EC225, NHIndustries NH-90 and Sikorsky S-92.[48]

South Korea has recognised the need to modernse their airborne mine countermeasures (AMCM) maritime helcopter fleet, and the AW101 is one of the helicopters being studied for the role.[49]

In November 2007, Algeria signed a contract for six AW101 helicopters.[50] This is one of several deals that may potentially follow according to the MOD.[51]

VIP and other usage

AgustaWestland developed a luxury variant of the AW101, the AW101 VVIP (Very Very Important Person, i.e. a head of state), targeted at business and VIP customers.[52] In mid-2008 it was revealed that a Saudi Arabian customer had ordered two VVIP AW101s.[53]

The United States Marine Corps has acquired two AW101 VH-71 helicopters as part of its efforts to replace its Marine One helicopters.[54] However the project itself was halted when funding on the programme was cut on 6 April 2009,[55] though it is likely to see a revival.[56]

India has ordered 12 AW-101 helicopters, for the Indian President and Prime Minister.[57][58] The AW-101 was selected after competing against the Sikorsky S-92 "Superhawk" in field trials in 2008. One particular requirement was that the helicopter have "a high tail boom" to allow the Prime Minister's car to come closer to the rear exit staircase for reduced exposure to threats.[59]

Variants

- Model 110

- Italian Navy ASW/ASuW variant, eight built.

- Model 111

- Royal Navy ASW/ASuW variant, designated Merlin HM1 by customer, 44 built.

- Model 112

- Italian Navy Early Warning variant, four built.

- Model 300

- Italian-built prototype civil passenger variant, one built.

- Model 410

- Italian Navy transport variant, eight built.

- Model 411

- Royal Air Force transport variant, designated Merlin HC3 by customer, 22 built.

- Model 500

- Prototype utility variant with rear-ramp, two built.

- Model 510

- Civil transport variant, two built.

- Model 511

- Canadian Forces search and rescue variant, designated CH-149 Cormorant by customer, 15 built.

- Model 512

- Royal Danish Air Force variant for search and rescue and transport, 14 built.

- Model 514

- Portuguese Air Force search and rescue variant, six built.

- Model 515

- Portuguese Air Force fisheries protection variant, two built.

- Model 516

- Portuguese Air Force combat search and rescue, four built.

- Model 518

- Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force mine countermeasures and transport, two built.

- Model 519

- Transport variant for the United States Marine Corps as the VH-71 Kestrel, five built.

- Merlin HM1

- Royal Navy designation for the Model 111.

- Merlin HM2

- Avionics retrofitting for 30 RN HM1s to be performed by Lockheed Martin for the Royal Navy. First flight expected late 2010.

- Merlin HC3

- Royal Air Force designation for the Model 411.

- Merlin HC3A

- Royal Air Force designation for six former Royal Danish Air Force Model 512s modified to UK standards.

- CH-148 Petrel

- 33 originally ordered by the Canadian Forces, reduced to 28 and later cancelled.

- CH-149 Cormorant

- Canadian Forces designation for the Model 511 Search and rescue variant. (14 in service).

- VH-71 Kestrel

- USMC variant intended to serve as the US Presidential helicopter. Two in testing.

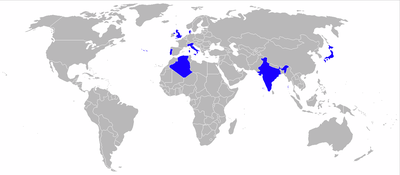

Operators

Military operators

- Algerian Navy

- (6 on Order)

- Royal Danish Air Force

- Eskadrille 722 (Squadron 722)

- VIP Transport Indian Air Force

- 12 on order

- Italian Navy

- 1°Gruppo Elicotteri

- 3°Gruppo Elicotteri

- Royal Navy

- 700M Naval Air Squadron (Operational Evaluation Unit) (2000–2008)

- 814 Naval Air Squadron

- 820 Naval Air Squadron

- 824 Naval Air Squadron

- 829 Naval Air Squadron

- Royal Air Force

Law enforcement operators

- Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department became the first civil customer for the type when they purchased a single example in 1998.

Notable accidents and incidents

Five Merlins have been written-off and one damaged in accidents, of which three have been due to problems with the tail rotor hub cracking.[citation needed]

- 21 January 1993 - Italian development Merlin PP2 (MMX600) crashed near Novara-Cameri airfield in Italy after an uncommanded application of the rotor brake in flight - four killed.[citation needed]

- 17 April 1995 - British development Merlin PP4 (ZF644) crashed near Yarcombe in Dorset, England.[citation needed]

- 20 August 1996 - Italian development Merlin PP7 (I-HIOI) was damaged in an accident when it turned over after the tail rotor drive failed on landing. The helicopter was repaired.[60]

- 27 October 2000 - British Royal Navy Merlin (ZH844) ditched near the Isle of Skye, Scotland after a hydraulic fire caused by the rotor brake being partially engaged.[61]

- 30 March 2004 - British Royal Navy Merlin (ZH859) crashed on take-off from RNAS Culdrose due to tail rotor hub cracking.[62]

- 15 November 2007 - During a medical evacuation on São Jorge Island, Azores, Portugal, a Portuguese Air Force Merlin caused injuries to five people when it suddenly and unexpectedly climbed by one meter in the middle of the embarking procedures. The pilot was then able to recover the control of the helicopter minimizing the damages. According to the air force spokesperson, this kind of incident is unheard of.[63]

Specifications (Merlin HM1)

General characteristics

- Crew: 4

- Capacity:

- 24 seated troops or

- 45 standing troops or

- 16 stretchers with medics

Performance

Armament

- Guns: 5× general purpose machine guns

- Bombs: 960 kg (2,116 lb) of anti-ship missiles (up to 2), homing torpedoes (up to 4), depth charges and rockets

Avionics

- Smiths Industries OMI 20 SEP dual-redundant digital automatic flight control system

- Navigation systems:

- BAE Systems LINS 300 ring laser gyro, Litton Italia LISA-4000 strapdown AHRS (naval variants)

- Tactical air navigation (TACAN), VHF Omnidirectional Radio range (VOR), instrument landing system (ILS)

- Radar:

- Selex Galileo Blue Kestrel 5000 maritime surveillance radar (ASW RN EH101s)

- Eliradar MM/APS-784 maritime surveillance radar (ASW Italian EH101s)

- Eliradar HEW-784 air/surface surveillance radar (AEW variants)

- Officine Galileo MM/APS-705B search/weather radar (Italian Navy Utility EH101s)

- Telephonics RDR-1600 weather avoidance radar (Royal Danish Air Force EH101s)

- Galileo APS-717 search/surveillance radar (Portuguese Air Force EH101s)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- ^ "EH-101 Merlin factsheet". Portuguese Air Force. Retrieved 5-02-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Danish Airforce factsheet". Danish Airforce. Retrieved 5-02-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Concept image of WG.34". Flight International. 25 November 1978.

- ^ Briganti, Giovanni de. "Agusta, Westland and Europe". defense-aerospace.com. Retrieved 5-02-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Aeronautica & Difesa, No. 14, Dec 1987, p. 34.

- ^ "Go-ahead for Anglo-Italian EH101 Helicopter". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology. MCB UP. 1984. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Twigge, Stephen (August 1992). "The EH101 helicopter: A fully integrated international collaborative program". Defense & Security Analysis. pp. 133–146.

- ^ Richardson, Ian (5 December 1989). "Westland banking on navy buying EH 101". Glasgow Herald.

- ^ McLaughlin, Audrey (28 July 1992). "Cold War 'copters a waste of money". Toronto Star.

- ^ Thompson, Allan (2 June 1995). "$2.6 billion sought for copters Military wants craft to replace aging Sea Kings". Toronto Star.

- ^ "Canada settles claim on Canceled Helicopters". New York Times. 24 January 1996.

- ^ Hotten, Russell (23 February 1995). "Westland tipped for MoD order". The Independent.

- ^ "Italian navy orders 16 EH-101 helicopters". Defense Daily. 10 October 1995.

- ^ Ford, Terry (1997). "Advances in rotorcraft". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology. pp. 447–452.

- ^ Barrie, D (23 December 2002). "Westland pushes additional Merlins for U.K. lift needs". Aviation Week & Space Technology. p. 29.

- ^ "Westland merger confirmed". BBC News. 26 July 2000.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (27 May 2004). "Italians take controls at UK helicopter maker". The Telegraph.

- ^ "Rotorcraft Report: AgustaWestland". Rotor & Wing. Access Intelligence, LLC. 2007-08-01.

The company re-branded its medium-lift EH101 transport the AW101 to reflect...the full integration of its Agusta and Westland...

- ^ Marks, N.G. (August 1989). "Polymer Composites for Helicopter Structures". 5 (8). Met. Mater.: 456–459.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Prouty, Ray. Helicopter Aerodynamics, Helobooks, 2003

- ^ Prince, J. Colin (5 June 1995). "Color AMLCD displays for the EH-101 helicopter". 2462. SPIE: 234–240.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Witt, Mike (Spring 1990). "Rolls-Royce—a fount of military power". 135 (1). RUSI Journal: 39–45.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "RTM322". Rolls-Royce plc. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ "FLIR Systems awarded contract to provide Thermal Imaging Systems for Royal Danish and Portuguese Air Forces; Contract valued at more than $10 million". Business Wire. 2 October 2002.

- ^ Rivers, Brendan P (1 November 2001). "Nordic Helo paths diverge". Journal of Electronic Defense.

The first had no specific requirements other than that it needed to include an EW controller, a radar-warning receiver, a missile-warning system, a laser-warning system, and a chaff/flare dispenser, with an optional RF jammer

- ^ Cox, Bob (1 November 2001). "Lockheed Martin teams with European firm to market new All-Weather Helicopter". Fort Worth Star.

As a transport, the EH-101 could be configured to carry 24 to 30 troops, up to five tons of cargo or up to 16 stretchers to carry wounded

- ^ Smith, Alan F (1 October 1997). "Aluminum-lithium alloys in helicopters". Advanced Materials & Processes.

- ^ Scott, Richard (9 December 2003). "Sea change". Flight International.

- ^ "Probe continues into Merlin crash". BBC News. 31 March 2004.

- ^ Jane's Defence Weekly 8 July 2009 p. 14

- ^ "Royal Navy begins process to replace Sea King Commando". Flight International. 30 April 1997.

- ^ "Ships and aircraft axed to pay for war against Taleban". Navy News. 16 December 2009.

- ^ Cobbold, Richard (April 1994). "The Maritime helicopter". Chief of the Defence staff. 139 (2). RUSI Journal: 56–63.

- ^ "Integrated Merlin Operational Support". Serco. Retrieved 5-02-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "78 Squadron Operational". Royal Air Force. 3 December 2007.

- ^ "MoD denies Merlin 'unsafe' claims". BBC News. 4 August 2009.

- ^ "Direzione Generale degli Armamenti Aeronautici: EH - 101". Italian Ministry of Defence.English translation

- ^ "AgustaWestland received a UKPd250 mil contract to supply 14 helicopters to Denmark". The Engineer. 21 September 2001.

- ^ "Forsvarets fejlindkøb står i kø". Berlingske Tidende. 4 February 2008.

- ^ a b "MCH-101 Airborne Mine Countermeasures (AMCM)". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ^ a b "First MCH-101 Helicopter Goes to Japan Defense Agency". KHI. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ^ "Milestone RTM322 Engine goes to Japan Defense Agency". KHI. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ "Kawasaki Aircraft". KHI. Retrieved 5-02-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "First Licence Built EH101 Delivered By Kawasaki". AgustaWestland. Retrieved 1-04-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Marubeni And AgustaWestland Sign Spares Support Agreement". AgustaWestland. Retrieved 01-04-2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ David, Adrian (11 April 2008). "Successful ops push up demand for AW101 copters". New Straits Times.

- ^ "The NAWSARH Project". Royal Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ Per Erlien Dalløkken (2009-05-07). "De fem kandidatene". Teknisk Ukeblad (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ Sung-ki, Jung (17 June 2008). "S. Korean Navy to Buy 4 Mine Sweeper Choppers by 2012". Korea Times.

- ^ "AgustaWestland, 400 million Euro contract in Algeria". Avionews. 20 November 2007.

- ^ "UK to sell military equipment to Algeria- paper". El-Khabar. 27 October 2009.

- ^ "EBACE 2008: Agusta Westland targets VVIPs with luxury AW101". Flight Daily News. 19 May 2008.

- ^ "Saudi Arabian customer orders two VVIP AgustaWestland AW-101s". Retrieved 2008-08-12. mirror

- ^ Page, Lewis (9 January 2009). "Could the Airbus A380 be the new Air Force One? - Obama's chopper is European". The Register.

- ^ Trimble, Stephen (2 June 2009). "US Navy terminates VH-71 presidential helicopter contract". flightglobal.com.

- ^ "VH-71 Presidential Helicopter Program: Background and Issues for Congress". Congressional Research Service. 5 June 2009.

- ^ Rao, Radhakrishna (10 August 2009). "India approves deals for Ka-31, AW101 helicopters". Flight International.

- ^ Kington, Tom (11 March 2010). "Indian AF To Buy 12 AgustaWestland AW101 Helos". Defense News.

- ^ "PM, President to get swanky copters". The Times of India. 30 July 2009.

- ^ "EH-101 flight operations suspended following mishap". Defense Daily. 3 September 1996.

- ^ Steele, David (28 October 2000). "Two aircraft crashes within one hour cost MoD £50m". The Herald.

- ^ "Flying restrictions after crash". BBC News. 6 April 2004.

- ^ Jornal de Notícias - Incidente com helicóptero da Força Aérea fez cinco feridos (in Portuguese), archived from the original on 17 December 2007