Tax increment financing: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

'''Tax Increment Financing''', or '''TIF''', is a public financing method which has been used for [[redevelopment]] and community improvement projects in many countries including the [[United States]] for more than 50 years. With [[Federal government of the United States|federal]] and [[U.S. state|state]] sources for redevelopment generally less available, TIF has become an often-used financing mechanism for [[municipalities]]. Similar or related approaches are used elsewhere in the world. See for example, [[Value capture]]. |

'''Tax Increment Financing''', or '''TIF''', is a public financing method which has been used for [[redevelopment]] and community improvement projects in many countries including the [[United States]] for more than 50 years. With [[Federal government of the United States|federal]] and [[U.S. state|state]] sources for redevelopment generally less available, TIF has become an often-used financing mechanism for [[municipalities]]. Similar or related approaches are used elsewhere in the world. See for example, [[Value capture]]. |

||

This is how TIF works |

==This is how TIF works== |

||

click on graph image to enlarge |

|||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

File:TIF_graph.pdf |

File:TIF_graph.pdf |

||

Revision as of 04:26, 23 May 2010

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (May 2008) |

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

Tax Increment Financing, or TIF, is a public financing method which has been used for redevelopment and community improvement projects in many countries including the United States for more than 50 years. With federal and state sources for redevelopment generally less available, TIF has become an often-used financing mechanism for municipalities. Similar or related approaches are used elsewhere in the world. See for example, Value capture.

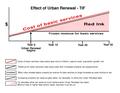

This is how TIF works

click on graph image to enlarge

Theory

TIF is a tool to use future gains in taxes to finance current improvements (which theoretically will create the conditions for those future gains). When a public project such as a road, school, or hazardous waste cleanup is carried out, there is often an increase in the value of surrounding real estate, and perhaps new investment (new or rehabilitated buildings, for example).

This increased site value and investment sometimes generates increased tax revenues. The increased tax revenues are the "tax increment." Tax Increment Financing dedicates tax increments within a certain defined district to finance debt issued to pay for the project. TIF is designed to channel funding toward improvements in distressed or underdeveloped areas where development might not otherwise occur. TIF creates funding for "public" projects that may otherwise be unaffordable to localities, by borrowing against future property tax revenues.[1]

Currently, thousands of TIF districts operate nationwide in the US, from small and mid-sized cities, to the State of California, which invented tax increment financing in 1952. California maintains over four hundred TIF districts with an aggregate of over $10 billion per year in revenues, over $28 billion of long-term debt, and over $674 billion of assessed land valuation (2008 figures).[2]

49 states and the District of Columbia have enabled legislation for tax increment financing. Arizona is now the only state without a tax increment financing law. While some states, such as California and Illinois, have used TIF for decades, many others have only recently passed or amended state laws that allow them to use this tool. [3]

Since the 1970s, a reduction in federal funding for redevelopment-related activities including spending increases, restrictions on municipal bonds which are tax-exempt bonds and an administrative transference of urban policy to local, lower-level governments, has led many cities to consider tax increment financing. State-imposed caps on municipal property tax collections and limits on the amounts and types of city expenditures have also caused local governments to adopt funding strategies like this as a kind of loophole through the restrictions.

Criticism

TIF districts are not without criticism. Although tax increment financing is one mechanism for local governments that does not directly rely on federal funds, many question whether TIF districts actually serve their resident populations. As investment in an area increases, it is not uncommon for real-estate values to rise and for gentrification to occur. An organization called Municipal Officials for Redevelopment Reform (MORR) holds regular conferences on redevelopment abuse.[4]

Further claims made by TIF opponents:

- Although generally sold to legislatures as a tool to redevelop blighted areas, some districts are drawn up where development would happen anyway such as prime areas at the edges of cities. California has had to pass legislation designed to curb this abuse.[5] [6]

- The designation as blighted can allow governmental condemnation of property through eminent domain. The famous Kelo v. City of New London Supreme Court case, where homes were condemned for a private development was about actions within a TIF district.

- Normal inflationary increases in property values are captured with districts, representing money that would have gone to the public coffers even without the financed improvements.

- Districts are drawn too large, capturing value, again, that would have been increased anyway.

- The process leads to favoritism for politically connected developers, lawyers, economic development directors and other implementers.

- Funding often goes toward what have been traditionally private improvements from which developers profit. When the public "invests" in these improvements it is the developers that still receive the return.

- Capturing the full tax increment and directing it to repay the development bonds ignores the fact that the incremental increase in property value likely requires an increase in the provision of public services, which will now have to be funded from elsewhere (often from subsides from less economically thriving areas). For example, the use of tax increment financing to create a large residential development means that public services from schools to public safety will need to be expanded, yet if the full tax increment is captured to repay the development bonds, other money will have to be [7].

Examples

Chicago

The city of Chicago, in Cook County, Illinois, has a significant number of TIF districts and has become a prime location for examining the benefits and disadvantages of TIF districts. The city runs 131 districts with tax receipts totaling upwards of $500 million for 2006.[8] Lori Healey, appointed commissioner of the city's Planning and Development department in 2005 was instrumental in the process of approving TIF districts as first deputy commissioner.

The Chicago Reader, a Chicago alternative newspaper published weekly, has published articles regarding tax increment financing districts in and around Chicago. Written by staff writer Ben Joravsky, the articles are critical of tax increment financing districts as implemented in Chicago.[9]

Given the influence and power held by Mayor Daley of Chicago, local, elected officials have been unwilling to criticize the Chicago's tax increment financing program due to Mayor Daley's unwavering support for these districts. Former Cook County Commissioner Michael Quigley was the exception, questioning the wisdom of expanding tax increment financing districts, calling for substantive reforms, and putting accountability into the governance of such districts. His office recently released a report on TIFs.[10]

Cook County Clerk David Orr, in order to bring transparency to Chicago and Cook County tax increment financing districts, began to feature information regarding Chicago area districts on his office's website.[11] The information featured includes City of Chicago TIF revenue by year, maps of Chicago and Cook County suburban municipalities' TIF districts.

The Neighborhood Capital Budget Group of Chicago, Illinois, a non-profit organization, advocated for area resident participation in capital programs. The group also researched and analyzed the expansion of Chicago's TIF districts. Though the organization closed on February 1, 2007, their research will be available on their website for six months.[12]

Albuquerque

Currently, the largest TIF project in America is located in Albuquerque, New Mexico: the $500 million Mesa del Sol development. Mesa del Sol is controversial in that the proposed development would be built upon a "green field" that presently generates little tax revenue and any increase in tax revenue would be diverted into a tax increment financing fund. This "increment" thus would leave governmental bodies without funding from the developed area that is necessary for the governmental bodies' operation.

Alameda, California

In 2009, SunCal Companies, an Irvine, California based developer, introduced a ballot initiative that embodied a redevelopment plan for the former Naval Air Station Alameda and a financial plan based in part on roughly $200 million worth of tax increment financing to pay for public amenities. SunCal structured the initiative so that the provision of public amenities was contingent on receiving tax increment financing, and on the creation of a community facilities (Mello-Roos) district, which would levy a special (extra) tax on property owners within the development.[13] In California, Community Redevelopment Law governs the use of tax increment financing by public agencies. [14]

Applications and administration

Cities use TIF to finance public infrastructure, land acquisition, demolition, utilities and planning costs, and other improvements including sewer expansion and repair, curb and sidewalk work, storm drainage, traffic control, street construction and expansion, street lighting, water supply, landscaping, park improvements, environmental remediation, bridge construction and repair, and parking structures.

State enabling legislation gives local governments the authority to designate tax increment financing districts. The district usually lasts 20 years, or enough time to pay back the bonds issued to fund the improvements. While arrangements vary, it is common to have a city government assuming the administrative role, making decisions about how and where the tool is applied.[15]

Most jurisdictions only allow bonds to be floated based upon a portion (usually capped at 50%) of the assumed increase in tax revenues. So, for example, if a $5,000,000 annual tax increment is expected in a development, which would cover the financing costs of a $50,000,000 bond, only a $25,000,000 bond would be typically allowed. Providing that the project is moderately successful, this would mean that a good portion of the expected annual tax revenues (in this case over $2,000,000) would be dedicated to other public purposes other than paying off the bond.

See also

References

- ^ Various, (2001). Tax Increment Financing and Economic Development, Uses, Structures and Impact. Edited by Craig L. Johnson and Joyce Y. Man. State University of New York Press.

- ^ California State Controller's Annual Report on Redevelopment Agencies, 2007-2008

- ^ Arkansas (2000), Washington (2001), New Jersey 2002, Delaware 2003, Louisiana 2003, North Carolina 2005, and New Mexico 2006.

- ^ "Redevelopment.com website". Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ^ "Redevelopment: The unknown government". Coalition for Redevelopment Reform. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ^ "Subsidizing Redevelopment in California" (PDF). Public Policy Institute of California. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ^ See Richard Dye and David Merriman, "The Effects of Tax-Increment Financing on Economic Development," 47 Journal of Urban Economics, no. 2 (2000) pp. 306-328

- ^ "City of Chicago TIF Revenue Totals by Year 1986-2006" (PDF). Cook County Clerk's Office. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "articles by Reader staff writer Ben Joravsky on Chicago's TIF (tax increment financing) districts". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "A Tale of Two Cities: Reinventing Tax Increment Financing" (PDF). Mike Quigley (Cook County Commissioner) website. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "TIFs 101: A taxpayer's primer for understanding TIFs". Cook County Clerk's Office. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Research". Neighborhood Capital Budget Group of Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ "Alameda Point Development Initiative Election Report Executive Summary Part I" (PDF). City of Alameda. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- ^ "California Community Redevelopment Law". Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- ^ "Growth Within Bounds: Report of the Commission on Local Governance for the 21st Century" (PDF). State of California. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

External links

- Subsidizing Redevelopment in California (1998). by Michael Dardia, Written for the Public Policy Institute of California

- Nathan A. Benefield's academic paper titled The Effects of Tax Increment Financing on Home Values in the City of Chicago (2003). Benefield's paper was prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

- Swenson & Eathington's Do Tax Increment Finance Districts in Iowa Spur Regional Economic and Demographic Growth? (2002)

- Weber's paper titled Making Tax Increment Financing (TIF) Work for Workforce Development: The Case of Chicago (1999)

- An abstract of Weber's Equity and Entrepreneurialism: The Impact of Tax Increment Financing on School Finance (2003).

- An abstract of Weber, et al.'s Does Tax Increment Financing Raise Urban Industrial Property Values? (2003)

- An abstract of Robinson's Hunger Discipline and Social Parasites: The Political Economy of the Living Wage (2004).

- An abstract of Man's Fiscal Pressure, Tax Competition and the Adoption of Tax Increment Financing (1999).

- Hubbell & Eaton's Tax Increment Financing in the State of Missouri (University of Missouri-Kansas City, 1997)

- Wood & Hughes' report for Center on Wisconsin Strategy (at University of Wisconsin–Madison) titled From Stumps to Dumps: Wisconsin's Anti-Environmental Subsidies (2001)

- Matthew Mayrl's report for Center on Wisconsin Strategy (at University of Wisconsin–Madison) titled Refocusing Wisconsin’s TIF System On Urban Redevelopment: Three Reforms (2005) and theExecutive Summary