Willie Mays: Difference between revisions

Entered Mays's sitcom appearances |

|||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

Mays' professional baseball career began in 1947, when he was still in high school, when he played briefly with the [[Chattanooga Choo-Choos]] in [[Tennessee]] during the summer, after school had let out. Shortly thereafter, Mays left the Choo-Choos, returned to his home state, and joined the [[Birmingham Black Barons]] of the [[Negro American League]]. Mays helped the Black Barons win their pennant and advance to the 1948 [[Negro Leagues]] World Series, where they lost 4 games to 1 to the [[Homestead Grays]]. Mays hit just .226 for the season, but his excellent fielding and baserunning made him a useful player. However, by playing professionally with the Black Barons, Mays jeopardized his opportunities to play high school sports in Alabama state competition, and this created some problems for him with high school administration at Fairfield, which wanted him on their teams, to sell tickets and help teams win.<ref>''Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend'', by [[James Hirsch]], 2010, Scribner, New York, [[ISBN]] 978-1-4165-4790-7, pp. 38-48.</ref> |

Mays' professional baseball career began in 1947, when he was still in high school, when he played briefly with the [[Chattanooga Choo-Choos]] in [[Tennessee]] during the summer, after school had let out. Shortly thereafter, Mays left the Choo-Choos, returned to his home state, and joined the [[Birmingham Black Barons]] of the [[Negro American League]]. Mays helped the Black Barons win their pennant and advance to the 1948 [[Negro Leagues]] World Series, where they lost 4 games to 1 to the [[Homestead Grays]]. Mays hit just .226 for the season, but his excellent fielding and baserunning made him a useful player. However, by playing professionally with the Black Barons, Mays jeopardized his opportunities to play high school sports in Alabama state competition, and this created some problems for him with high school administration at Fairfield, which wanted him on their teams, to sell tickets and help teams win.<ref>''Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend'', by [[James Hirsch]], 2010, Scribner, New York, [[ISBN]] 978-1-4165-4790-7, pp. 38-48.</ref> |

||

Over the next several years, a number of Major League baseball franchises sent scouts to watch him play. The first was the [[Atlanta Braves|Boston Braves]]. The scout who found him, Bud Maughn, referred him to the Braves, but they declined. Had the team taken an interest, the Braves franchise might have had Mays and [[Hank Aaron]] together in its outfield from 1954 to 1973. The [[Brooklyn Dodgers]] also scouted him, but concluded he could not hit the curve ball. Maughn then tipped a scout for the New York Giants, which signed Mays in 1950 and assigned him to their Class-B affiliate in [[Trenton, New Jersey]].<ref>[http://www.salon.com/people/bc/1999/07/13/mays/print.html Salon Brilliant Careers | Willie Mays<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

Over the next several years, a number of Major League baseball franchises sent scouts to watch him play. The first was the [[Atlanta Braves|Boston Braves]]. The scout who found him, Bud Maughn, referred him to the Braves, but they declined. Had the team taken an interest, the Braves franchise might have had Mays and [[Hank Aaron]] together in its outfield from 1954 to 1973. The [[Brooklyn Dodgers]] also scouted him, but concluded he could not hit the [[curve ball]]. Maughn then tipped a scout for the New York Giants, which signed Mays in 1950 and assigned him to their Class-B affiliate in [[Trenton, New Jersey]].<ref>[http://www.salon.com/people/bc/1999/07/13/mays/print.html Salon Brilliant Careers | Willie Mays<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

===Minor leagues=== |

===Minor leagues=== |

||

Revision as of 03:01, 30 June 2010

| Willie Mays | |

|---|---|

| |

| Center fielder | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| debut | |

| May 25, 1951, for the New York Giants | |

| Last appearance | |

| October, 1973, for the New York Mets | |

| Career statistics | |

| Batting average | .302 |

| Home runs | 660 |

| Hits | 3,283 |

| Runs batted in | 1,903 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| [[{{{hoflink}}}|Member of the {{{hoftype}}}]] | |

| Induction | 1979 |

| Vote | 94.7% (first ballot) |

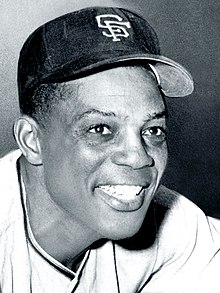

William Howard "Willie" Mays, Jr. (born May 6, 1931) is a retired American baseball player who played the majority of his career with the New York and San Francisco Giants before finishing with the New York Mets. Nicknamed The Say Hey Kid, Mays was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979, his first year of eligibility. Many consider him to be the greatest all-around player of all time.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Mays won two MVP awards and tied a record with 24 appearances in the All-Star Game. He ended his career with 660 career home runs, third at the time of his retirement, and currently fourth all-time. In 1999, Mays placed second on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players, making him the highest-ranking living player. Later that year, he was also elected to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. Mays is the only Major League player to have hit a home run in every inning from the 1st through the 16th. He finished his career with a record 22 extra-inning home runs. Mays is one of five NL players to have eight consecutive 100-RBI seasons, along with Mel Ott, Sammy Sosa, Chipper Jones and Albert Pujols. Mays hit 50 or more home runs in both 1955 and 1965. This time span represents the longest stretch between 50 plus home run seasons for any player in Major League Baseball history.

Mays' first Major League manager, Leo Durocher, said of Mays: "He could do the five things you have to do to be a superstar: hit, hit with power, run, throw, and field. And he had that other ingredient that turns a superstar into a super superstar. He lit up the room when he came in. He was a joy to be around."[8]

Upon his Hall of Fame induction, Mays was asked who was the best player that he had seen during his career. Mays replied, "I thought I was."[9] Ted Williams once said "They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays."[10];[11]

Early life

Mays was born in Westfield, Alabama, just outside of Birmingham, Alabama. His father, who was named for president William Howard Taft, was a talented baseball player with the Negro team for the local iron plant. The elder Mays was so quick he was nickamed "Kitty Cat." Willie played with him as a teen on the factory squad. His mother had run on the track and field team.

Mays was gifted in multiple sports, averaging 17 points a game (quite high for the time) for the Fairfield Industrial H.S. basketball team, and more than 40 yards a punt in football. He also starred at quarterback. He graduated from Fairfield in 1950.

Early professional career

Negro leagues

Mays' professional baseball career began in 1947, when he was still in high school, when he played briefly with the Chattanooga Choo-Choos in Tennessee during the summer, after school had let out. Shortly thereafter, Mays left the Choo-Choos, returned to his home state, and joined the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. Mays helped the Black Barons win their pennant and advance to the 1948 Negro Leagues World Series, where they lost 4 games to 1 to the Homestead Grays. Mays hit just .226 for the season, but his excellent fielding and baserunning made him a useful player. However, by playing professionally with the Black Barons, Mays jeopardized his opportunities to play high school sports in Alabama state competition, and this created some problems for him with high school administration at Fairfield, which wanted him on their teams, to sell tickets and help teams win.[12]

Over the next several years, a number of Major League baseball franchises sent scouts to watch him play. The first was the Boston Braves. The scout who found him, Bud Maughn, referred him to the Braves, but they declined. Had the team taken an interest, the Braves franchise might have had Mays and Hank Aaron together in its outfield from 1954 to 1973. The Brooklyn Dodgers also scouted him, but concluded he could not hit the curve ball. Maughn then tipped a scout for the New York Giants, which signed Mays in 1950 and assigned him to their Class-B affiliate in Trenton, New Jersey.[13]

Minor leagues

After Mays had a batting average of .353 in Trenton, N.J., he began the 1951 season with the class AAA Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. During his short time span in Minneapolis, Mays played with two other future Hall of Famers, Hoyt Wilhelm and Ray Dandridge. Batting .477 in 35 games and playing excellent defense, Mays was called up to the Giants on May 24, 1951; he appeared in his first major league game the next day in Philadelphia. Mays moved to Harlem, New York, where his mentor was a New York State Boxing Commission official and former Harlem Rens basketball legend Frank "Strangler" Forbes.

Major leagues

New York Giants (1951–57)

Mays began his major league career with no hits in his first twelve at bats. On his thirteenth at bat, he hit a homer over the left field fence of the Polo Grounds off Warren Spahn.[14] Spahn later joked, "I'll never forgive myself. We might have gotten rid of Willie forever if I'd only struck him out." Mays' average improved steadily throughout the rest of the season. Although his .274 average, 68 RBI and 20 homers (in 121 games) were among the lowest of his career, he still won the 1951 Rookie of the Year Award. During the Giants' comeback in August and September 1951 to overtake the Dodgers in the 1951 pennant race, Mays' fielding, and great arm were often instrumental to several important Giant victories.[15] Mays ended the regular season in the on-deck circle when Bobby Thomson hit the Shot Heard 'Round the World against the Brooklyn Dodgers, to win the three-game playoff by 2 games to 1, after the teams had tied at the end of the regular season.

The Giants went on to meet the New York Yankees in the 1951 World Series. Mays was part of the first all African-American outfield in major league history, along with Hall of Famer Monte Irvin and Hank Thompson, in Game One of the 1951 World Series.[16] Mays hit poorly, while the Giants lost the series four games to two. The six-game set was the only time that Mays and the aging Joe DiMaggio would play on the same field.[17]

Mays was a popular figure in Harlem. Magazine photographers were fond of chronicling his participation in local stickball games with kids. It was said that in the urban game of hitting a rubber ball with the handle of an adapted broomstick, Mays could hit a shot that measured "six sewers" (the distance of six consecutive NYC manhole covers- nearly 300 feet).

The United States Army drafted Mays in 1952 and he subsequently missed most of the 1952 season and all of the 1953 season. Despite the conflict in Korea, Mays spent most of his time in the army playing baseball at Fort Eustis, Va.[18] Mays missed about 266 games due to military service.

Mays returned to the Giants in 1954, hitting for a league-leading .345 batting average and slugging 41 home runs. Mays won the National League Most Valuable Player Award and the Hickok Belt as top professional athlete of the year. In addition, the Giants won the National League pennant and the 1954 World Series, sweeping the Cleveland Indians in four games. The 1954 series is perhaps best remembered for "The Catch," an over-the-shoulder running grab by Mays in deep center field of the Polo Grounds of a long drive off the bat of Vic Wertz during the eighth inning of Game 1. Considered the iconic image of Mays' playing career and one of baseball's most memorable fielding plays[19], the catch prevented two Indians runners from scoring, preserving a tie game. The Giants won the game in the 10th inning, with Mays scoring the winning run.

Mays went on to perform at a high level each of the last three years the Giants were in New York City. In 1956, he hit 36 homers and stole 40 bases, being only the second player and first National League player to join the "30-30 club". In 1957, the first season the Gold Glove award was presented, he won the first of twelve consecutive Gold Glove Awards. At the same time, Mays continued to finish in the NL's top five in a variety of offensive categories. Mays, Roberto Clemente (also with twelve) , Al Kaline, and Ken Griffey, Jr. are the only outfielders to have ten or more career Gold Gloves. 1957 also saw Mays become the fourth player in Major League history to join the 20–20–20 club (2B,3B,HR). No player had joined the "club" since 1941. George Brett accomplished the feat in 1979; and both Curtis Granderson and Jimmy Rollins joined the club in 2007. Mays also stole 38 bases in 1957; Mays was the second player in baseball history (after Frank Schulte in 1911) to reach 20 in each of those four categories (doubles, triples, homers, steals) in the same season. Both Jimmy Rollins and Curtis Granderson achieved the feat in 2007.[20]

San Francisco Giants (1958–72)

The Giants were not one of the top teams in the National League between 1955 and 1960; they never finished higher than third place or won more than 83 games in a season. After the 1957 season, the Giants franchise and Mays relocated to San Francisco, California. Mays bought two homes in San Francisco, then lived in nearby Atherton.[21][22] 1958 found Mays vying for the NL batting title, down to the final game of the season, just as in 1954. Mays collected three hits in the game, to finish with a career-high .347, but Philadelphia Phillies' Richie Ashburn won the title with a .350 average. In 1959 the Giants led by two games with only eight games to play, but could only win two of their remaining games and finished fourth, as their pitching staff collapsed due to overwork of their top hurlers. The Dodgers won the pennant following a playoff with the Milwaukee Braves.[23]

Alvin Dark was hired to manage the Giants before the start of the 1961 season, and named Mays team captain. The improving Giants finished '61 in third place and won 85 games, more than any of the previous six campaigns. Mays had one of his best games on April 30, 1961, hitting 4 home runs against the Milwaukee Braves in County Stadium. Mays went 4 for 5 at the plate and was on deck for a chance to hit a record fifth home run when the Giants' half of the ninth inning ended.[24][25] Mays is the only Major Leaguer to have both a 3-triple game and a 4-HR game.[26][27]

The Giants won the National League pennant in 1962, with Mays leading the team in eight offensive categories. The team finished the regular season in a tie for first place with the Los Angeles Dodgers, and went on to win a three-game playoff series versus the Dodgers, advancing to play in the World Series. The Giants lost to the Yankees in seven games, and Mays hit just .250 with only two extra-base hits. It was his last World Series appearance as a member of the Giants.

In both the 1963 and 1964 seasons Mays batted in over 100 runs, and hit 85 total home runs. On July 2, 1963, Mays played in a game when future Hall of Fame members Warren Spahn and Juan Marichal each threw fifteen scoreless innings. In the bottom of the sixteenth inning, Mays hit a home run off Spahn for a 1–0 Giants victory.[28]

Mays won his second MVP award in 1965 behind a career-high 52 home runs. He also hit career home run number 500 on September 13, 1965 off Don Nottebart. Warren Spahn, off whom Mays hit his first career home run, was his teammate at the time. After the home run, Spahn greeted Mays in the dugout, asking "Was it anything like the same feeling?" Mays replied "It was exactly the same feeling. Same pitch, too."[29] On August 22, 1965, Mays and Sandy Koufax acted as peacemakers during a 14-minute brawl between the Giants and Dodgers after San Francisco pitcher Juan Marichal had bloodied Dodgers catcher John Roseboro with a bat.[30]

Mays played in over 150 games for thirteen consecutive years (a major-league record) from 1954 to 1966. In 1966, his last with 100 RBIs, Mays finished third in the NL MVP voting. It was the ninth and final time he finished in the top five in the voting for the award.[31] In 1970, the Sporting News named Mays as the "Player of the Decade" for the 1960s.

Willie hit career home run number 600 off San Diego's Mike Corkins in September 1969. Plagued by injuries that season, he managed only thirteen home runs. Mays enjoyed a resurgence in 1970, hitting twenty-eight homers and got off to a fast start in 1971, the year he turned 40. He had fifteen home runs at the All Star break, but faded down the stretch and finished with eighteen. Mays helped the Giants win the West division title that year, but they lost the NLCS to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

During his time on the Giants, Mays was friends with fellow player Bobby Bonds. When Bobby's son, Barry Bonds, was born, Bobby asked Willie Mays to be Barry's godfather. Mays and the younger Bonds maintained a close relationship ever since.

New York Mets (1972–73)

In May 1972, the 41-year-old Mays was traded to the New York Mets for pitcher Charlie Williams and $50,000 ($364,200 in current dollar terms).[32] At the time, the Giants franchise was losing money. Owner Horace Stoneham could not guarantee Mays an income after retirement and the Mets offered Mays a position as a coach upon his retirement.[33]

Mays had remained popular in New York long after the Giants had left for San Francisco, and the trade was seen as a public relations coup for the Mets. Mets owner Joan Whitney Payson, who was a minority shareholder of the Giants when the team was in New York, had long desired to bring Mays back to his baseball roots, and was instrumental in making the trade.[34] On May 14, 1972 in his Mets debut, Mays put New York ahead to stay with a 5th-inning home run against Don Carrithers and his former team, the Giants, on a rainy Sunday afternoon at Shea Stadium. Then on August 17, 1973 in a game against the Cincinnati Reds with Don Gullett on the mound, Willie hit a 4th inning solo home run over the right center field fence. This was his 660th and last of his illustrious major league career.

Mays played a season and a half with the Mets before retiring, appearing in 133 games. The New York Mets honored him on September 25, 1973 (Willie Mays' Night) where he thanked the New York fans and said good-bye to America. He finished his career in the 1973 World Series, which the Mets lost to the Oakland Athletics in seven games. Mays got the first hit of the Series, but had only seven at-bats (with two hits). He also fell down in the outfield during a play where he was hindered by the glare of the sun; Mays later said "growing old is just a helpless hurt." In 1972 and 1973, Mays was the oldest regular position player in baseball. He became the oldest position player to appear in a World Series game.[35]

Mays retired after the 1973 season with a lifetime batting average of .302 and 660 home runs. His lifetime total of 7,095 outfield fielding putouts remains the major league record.[35]

Post-playing days

After Mays stopped playing baseball, he remained an active personality. Just as he had during his playing days, Mays continued to appear on various TV shows, in films, and in other forms of non-sports related media. He remained in the New York Mets organization as their hitting instructor until the end of the 1979 season.[36] It was there where he taught future Mets' star Lee Mazzilli his famous basket catch.

On January 23, 1979, Mays was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. He garnered 409 of the 432 ballots cast (roughly 95 percent)[37]; referring to the other 23 voters, acerbic New York Daily News columnist Dick Young wrote, "If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn't vote for him. He dropped the cross three times, didn't he?"[19]

Mays took up golf a few years after his promotion to the major leagues, and quickly became an accomplished player, playing to a handicap of about 4. After he retired, he played golf frequently in the San Francisco area.[38]

Shortly after his Hall of Fame election, Mays took a job at the Park Place Casino (now Bally's Atlantic City) in Atlantic City, New Jersey. While there, he served as a Special Assistant to the Casino's President and as a greeter; Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle was also a greeter during that time. When Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn heard of this, he suspended both men from involvement in organized baseball for violating the league's rules on gambling. Peter Ueberroth, Kuhn's successor, lifted the suspension in 1985.

Since 1986, Willie Mays has served as Special Assistant to the President of the San Francisco Giants. Mays' number 24 is retired by the San Francisco Giants. AT&T Park, the Giants stadium, is located at 24 Willie Mays Plaza. In front of the main entrance to the stadium is a larger-than-life statue of Mays.

In May 2009, Mays gave the commencement address to the graduating class of 2009 at San Francisco State University.

On February 10, 2010, Mays appeared on The Daily Show, discussing his career and a new biography, Willie Mays: The Life, the Legend, by James S. Hirsch.

Special honors, tributes, and recognitions

When Mays' godson Barry Bonds tied him for third on the all-time home run list, Mays greeted and presented him with a diamond-studded Olympic torch (given to Mays for his role in carrying the Olympic Torch during its tour through the U.S.). In 1992, when Bonds signed a free agent contract with the Giants, Mays personally offered Bonds his retired #24 (the number Bonds wore in Pittsburgh) but Bonds declined, electing to wear #25 instead, honoring his father Bobby Bonds who wore #25 with the Giants.[39]

Willie Mays Day was proclaimed by former mayor Willie Brown and reaffirmed by mayor Gavin Newsom to be every May 24 in San Francisco, paying tribute not only to his birth in the month (May 6), but also to his name (Mays) and jersey number (24). The date is also the anniversary of his call-up to the major leagues.[40]

AT&T Park is located at 24 Willie Mays Plaza.

On May 24, 2004, during the fifty-year anniversary of The Catch, Willie Mays received an honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters degree from Yale University.[41]

On December 6, 2005, he was recognized for his accomplishments on and off the field when he received the Bobby Bragan Youth Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award.

On June 10, 2007, Willie Mays received an honorary doctorate from Dartmouth College.

At the 2007 All-Star Game in San Francisco, Mays received a special tribute for his legendary contributions to the game, and threw out the ceremonial first pitch.

On December 5, 2007, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Mays into the California Hall of Fame, located at The California Museum for History, Women and the Arts.[42]

On June 4, 2008, Community Board 10 in Harlem NYC, voted unanimously to name an 8 block service Road that connects to the Harlem River Drive from 155th Street to 163rd Street running adjacent to his beloved Polo Grounds—Willie Mays Drive.[43]

On May 23, 2009, Willie Mays received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from San Francisco State University.

On June 14, 2009, he accompanied US President Barack Obama to St. Louis aboard Air Force One for the Major League All-Star Game.[44]

On May 6, 2010, on the occasion of his 79th birthday, Mays appeared on the floor of the California State Senate where they proclaimed it Willie Mays Day in the state.

On May 15, 2010, May was awarded the MLB Beacon of Life Award at the Civil Rights game at Great American Ballpark.

Jersey Retired by San Francisco Giants;

:

:

Willie Mays: OF, 1951–72

1956 Willie Mays Major League Negro-American All-Stars Tour

In 1956, Willie Mays got many of Major League Baseball's biggest black stars to go on a tour around the country after the season had ended to play exhibition games. While much of the tour has gone undocumented, one venue the tour made a stop in was Andrews Field [45], located in Fort Smith, Arkansas, on October 16. Among the players to play in that game were Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron, Elston Howard, Monte Irvin, Gene Baker, Charlie Johnson, Sam Jones, Hank Thompson, and Joe Black.

Television Appearances

In addition to appearances in baseball documentaries and on talk shows, Mays has appeared in several sitcoms over the years, always as himself. He was in three episodes of The Donna Reed Show: "Play Ball" and "My Son the Catcher" (both 1964) and "Calling Willie Mays" (1966). Also in 1966, he appeared in the "Twitch or Treat" episode of Bewitched, in which Darrin Stephens asks if Mays is a witch, and Samantha Stephens replies, "The way he hits? What else?" In 1989, he appeared in My Two Dads, in the episode "You Love Me, Right?", and in the episode "The Field" of Mr. Belvedere. Additionally, he performed "Say Hey: The Willie Mays Song" on episode 4.46 of The Colgate Comedy Hour in 1954.[5]

Personal life

Willie Mays, Jr. was born to Ann and Willie Howard Mays, Sr., who divorced when he was three years old. Mays was raised mainly by his aunt, Sarah. He learned baseball and other sports from his father and his father's Industrial League teammates.

Mays was married to the former Margherite Wendell Chapman in 1956. His adopted[46] son, Michael was born in 1959. He divorced in 1962 or 1963, varying by source. In November 1971, Mays married Mae Louise Allen.

Origin of "Say Hey Kid" nickname

It is not clear how Mays became known as the "Say Hey Kid". One story is that in 1951, Barney Kremenko, a writer for the New York Journal, having overheard Mays blurt "'Say who,' 'Say what,' 'Say where,' 'Say hey,'" proceeded to refer to Mays as the 'Say Hey Kid'.[47]

The other story is that Jimmy Cannon created the nickname because, when Mays arrived in the minors, he did not know everyone's name. "You see a guy, you say, 'Hey, man. Say hey, man,' " Mays said. "Ted was the 'Splinter'. Joe was 'Joltin' Joe'. Stan was 'The Man'. I guess I hit a few home runs, and they said there goes the 'Say Hey Kid.'"[48]

While known as "The Say Hey Kid" to the public, Mays's nickname to friends, close acquaintances and teammates is "Buck."[49] Buck was an abbreviation or corruption of his nickname in Harlem and Negro League circles, "Buttdust" -- a common appellation for Black Americans said to have strong or prominent gluteal musculature (so that their "butts" made contact with road dust). Some listeners may have assumed friends were calling Mays "Buckduck" and shortened it to "Buck." Some Giants players referred to him, their team captain, as "Cap."

See also

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- 500 home run club

- List of Major League Baseball Home Run Records

- Top 500 home run hitters of all time

- MLB players who have hit 30 or more home runs before the All-Star break

- List of major league players with 2,000 hits

- List of Major League Baseball players with 400 doubles

- List of Major League Baseball players with 100 triples

- List of Major League Baseball players with 1000 runs

- List of Major League Baseball players with 1000 RBIs

- List of Major League Baseball leaders in career stolen bases

- 3000 hit club

- 300-300 club

- 30-30 club

- 20–20–20 club

- 3000-300 club

- 3000-500 club

- 50 home run club

- List of Major League Baseball batting champions

- List of Major League Baseball home run champions

- List of Major League Baseball runs scored champions

- List of Major League Baseball stolen base champions

- List of Major League Baseball triples champions

- Batters with four home runs in one game

- Major League Baseball hitters with three home runs in one game

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

References and notes

- ^ Allen, Bob; Gilbert, Bill (2000). The 500 Home Run Club: Baseball's 16 Greatest Home Run Hitters from Babe Ruth to Mark McGwire. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 145. ISBN 1582612897.

- ^ Lombardi, Stephen M. (2005). The Baseball Same Game: Finding Comparable Players from the National Pastime. iUniverse. p. 86. ISBN 0595354572.

- ^ Kalb, Elliott (2005). Who's Better, Who's Best in Baseball?: Mr. Stats Sets the Record Straight on the Top 75 Players of All Time. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0071445382.

- ^ Shannon, Mike (2007). Willie Mays: Art in the Outfield. University of Alabama Press. p. 89. ISBN 0817315403.

- ^ Markusen, Bruce (2000). Roberto Clemente: The Great One. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 140. ISBN 1582613125.

- ^ Hinton, Chuck (2002). My Time at Bat: A Story of Perseverance. Christian Living Books. p. 59. ISBN 1562290037.

- ^ Barra, Allen (2004). Brushbacks and Knockdowns: The Greatest Baseball Debates of Two Centuries. Macmillan Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 031232247X.

- ^ [1] [2]

- ^ Albuquerque Journal Online

- ^ National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum: The Hall of Famers

- ^ Willie's Time, by Charles Einstein.

- ^ Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, by James Hirsch, 2010, Scribner, New York, ISBN 978-1-4165-4790-7, pp. 38-48.

- ^ Salon Brilliant Careers | Willie Mays

- ^ ESPN.com: Mays brought joy to baseball

- ^ Willie Mays, by Matt von Albade, Tempo Books, Grosset & Dunlop, Inc. NY. copyright 1966, pp. 60–75 first printing, August 1966, Library of Congress Number 66-17205

- ^ Willie Mays, by Arnold Hano, Tempo Books, Grosset & Dunlop, Inc. NY. copyright 1966, p.80 first printing, August 1966, Library of Congress Number 66-17205

- ^ The Series, an illustrated history of Baseball's postseason showcase, 1903–1993, The Sporting News, copyright 1993, The Sporting News Publishing Co. pp. 144–145 ISBN 0-89204-476-4

- ^ BIOPROJ.SABR.ORG :: The Baseball Biography Project

- ^ a b http://espn.go.com/sportscentury/features/00215053.html

- ^ The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball

- ^ Streetwise: Willie Mays – Western Neighborhoods Project – San Francisco History

- ^ Mary Kay Linge, Willie Mays: A Biography (Greenwood Press, 2005), p.151.

- ^ The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (6th edition), 1985.

- ^ April 30, 1961 box score and play-by-play. Mays flied out to center field in leading off the 5th.

- ^ The Baseball Page

- ^ September 15, 1960 San Francisco Giants at Philadelphia Phillies Play by Play and Box Score – Baseball-Reference.com

- ^ April 30, 1961 San Francisco Giants at Milwaukee Braves Box Score and Play by Play – Baseball-Reference.com

- ^ July 2, 1963 Milwaukee Braves at San Francisco Giants Box Score and Play by Play – Baseball-Reference.com

- ^ The majesty of Mays

- ^ Letting Off Steam – confrontations between players, fans and umpires | Baseball Digest | Find Articles at BNET.com

- ^ He also finished sixth in the balloting three times.

- ^ "Mays Trade (at bottom)". Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ Shaun McCormack, Willie Mays (Rosen Publishing Group, 2003).

- ^ Post, Paul; and Lucas, Ed. "Turn back the clock: Willie Mays played a vital role on '73 mets; despite his age, future Hall of Famer helped young New York club capture the 1973 National League pennant", Baseball Digest, March 2003. Accessed July 15, 2008. "Mets owner Joan Payson had always wanted to bring the `Say Hey Kid' back to his baseball roots, and she finally pulled it off in a deal that shocked the baseball world."

- ^ a b Willie's Time, by Charles Einstein

- ^ "Mays on the IMDBb". Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- ^ [3]

- ^ Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, by James Hirsch, 2010.

- ^ "Bonds to Wear No. 25". New York Times. December 11, 1992.

- ^ Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, by James Hirsch

- ^ [4] [dead link]

- ^ Mays inducted into California Hall of Fame. California Museum. Retrieved 2007.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Lombardi, Frank (July 5, 2008). "Street fight leaves Willie Mays benched". New York Daily News.

- ^ Willie Mays aboard Air Force One with President Obama on YouTube

- ^ http://www.baseball-reference.com/minors/park.cgi?id=AR010

- ^ Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend, by James Hirsch, 2010, Scribner, New York, p. 6.

- ^ "Mays earns his nickname". Retrieved October 21, 2006.

- ^ "Article on Mays". Retrieved October 21, 2006.

- ^ "eMuseum: Willie Mays". Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

References

- David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman & Michael Gershman, ed. (2000). Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Total/Sports Illustrated.

- "Willie's Time: A Memoir Of Another America", by Charles Einstein

- Willie Mays, by Arnold Hano, Tempo Books, Grosset & Dunlop, Inc. NY. copyright 1966, first printing, August 1966, Library of Congress Number 66-17205

- The Series, an illustrated history of Baseball's postseason showcase, 1903–1993, The Sporting News, copyright 1993, The Sporting News publishing co. ISBN 0-89204-476-4

External links

- Willie Mays at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs

- Willie Mays article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- Willie Mays: Say Hey! – slideshow by Life magazine

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Major League Baseball center fielders

- New York Giants (NL) players

- San Francisco Giants players

- New York Mets players

- New York Mets coaches

- African American baseball players

- Negro league baseball players

- Birmingham Black Barons players

- National League All-Stars

- Baseball players from Alabama

- National League batting champions

- National League home run champions

- National League stolen base champions

- Gold Glove Award winners

- Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year Award winners

- Major League Baseball All-Star Game MVPs

- United States Army soldiers

- People from Jefferson County, Alabama

- People from New Rochelle, New York

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Trenton Giants players

- Minneapolis Millers (baseball) players

- 1931 births

- Living people