Wounded Knee Massacre: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Campaignbox Pine Ridge Campaign}} |

{{Campaignbox Pine Ridge Campaign}} |

||

The '''Wounded Knee Massacre''' was the last major armed conflict between the [[Great Sioux Nation]] and the [[United States of America]], and was later described as a "massacre" in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. [http://www.dreamscape.com/morgana/wkmiles.htm] On [[December 29]], [[1890]], the cavalry troops of the [[U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment|U.S. 7th Cavalry]] opened fire, also using four [[Hotchkiss gun]]s (capable of firing two pound explosive [[Shell (projectile)|shell]]s, fifty times per minute), against a surrounded encampment of Minneconjou [[Lakota]] [[Sioux]], while cavalry troops were disarming them. Since the very thorough disarmament had almost been completed, the Sioux fought back using their hands, weapons from cavalry casualties, or weapons recovered from the stacks of seized weapons. |

The '''Wounded Knee Massacre''' was the last major armed conflict between the [[Great Sioux Nation]] and the [[United States of America]], and was later described as a "massacre" in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. [http://www.dreamscape.com/morgana/wkmiles.htm] On [[December 29]], [[1890]], the cavalry troops of the [[U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment|U.S. 7th Cavalry]] opened fire, also using four [[Hotchkiss gun]]s (capable of firing two pound explosive [[Shell (projectile)|shell]]s, fifty times per minute), against a surrounded encampment of Minneconjou [[Lakota]] [[Sioux]], while cavalry troops were disarming them. Since the very thorough disarmament had almost been completed, the Sioux fought back using their hands, weapons from cavalry casualties, or weapons recovered from the stacks of seized weapons. 153 largely disarmed [[Sioux]] were killed during the chaotic conflict, as well as 25 cavalrymen deaths largely from friendly fire. An unknown number of the approximately 150 unaccounted for [[Sioux]] died from [[exposure]] after fleeing the chaos. |

||

==Prelude to the Incident== |

==Prelude to the Incident== |

||

Revision as of 21:10, 30 January 2006

| Wounded Knee massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Indian Wars | |||||||

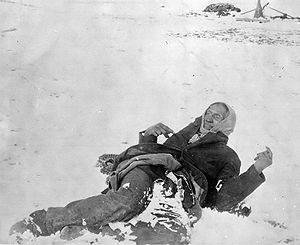

Miniconjou Chief Big Foot lies dead in the snow | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Great Sioux Nation | United States | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Big Foot | James W. Forsyth | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

120 men 230 women and children | 500 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

150 killed 50 wounded |

25 killed 39 wounded | ||||||

Template:Campaignbox Pine Ridge Campaign The Wounded Knee Massacre was the last major armed conflict between the Great Sioux Nation and the United States of America, and was later described as a "massacre" in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. [1] On December 29, 1890, the cavalry troops of the U.S. 7th Cavalry opened fire, also using four Hotchkiss guns (capable of firing two pound explosive shells, fifty times per minute), against a surrounded encampment of Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, while cavalry troops were disarming them. Since the very thorough disarmament had almost been completed, the Sioux fought back using their hands, weapons from cavalry casualties, or weapons recovered from the stacks of seized weapons. 153 largely disarmed Sioux were killed during the chaotic conflict, as well as 25 cavalrymen deaths largely from friendly fire. An unknown number of the approximately 150 unaccounted for Sioux died from exposure after fleeing the chaos.

Prelude to the Incident

Sometime in 1890, Jack Wilson, a Native American religious leader, claimed that during the total eclipse of the sun on January 1, 1889, he experienced a revelation that identified him as the messiah of his people. The spiritual movement he subsequently established became known as the Ghost Dance, a syncretic mix of Paiute spiritualism and Shaker Christianity. Although Wilson preached that earthquakes would be sent to kill all white people, he also taught that until judgment day, Native Americans were to live in peace and not refuse to work for whites.

Two early converts to the Ghost Dance religion were the Lakota warriors of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Kicking Bear and Short Bull. Both stated that Wilson levitated before them, though they interpreted his statements differently. They rejected Wilson's claims to be the Messiah, and believed that the Messiah would not arrive until 1891. They also rejected Wilson's pacifism, and believed that special garments, called Ghost Shirts, would act as bulletproof armor.

Though perhaps a majority of Pine Ridge Lakota converted to the Ghost Dance Religion, Chief Sitting Bull was not among them. However, he granted practitioners religious freedom. Federal officials misconstrued Sitting Bull's tolerance as full support, and attempted to arrest him on December 15, 1890. For unclear reasons a gun battle ensued, and Sitting Bull was killed.

Sitting Bull's half-brother, Big Foot, was chosen as the new leader of the tribe. On the way to help fellow chief Red Cloud make peace with the Whites, Big Foot was intercepted by Major Samuel Whitside of the 7th Cavalry. Whitside transferred Big Foot to an army ambulance due to his severe pneumonia and escorted the Native Americans to their camp for the night at Wounded Knee Creek. The army supplied the Native Americans with some tents and rations, and then conducted a census, determining that there were 120 males and 230 women and children.

The next morning, the Lakota found that additional 7th Cavalry troopers with more Hotchkiss guns had arrived during the night. The cannons were set up on a low hill overlooking the Lakota encampment. Colonel James W. Forsyth had assumed command of the soldiers. Forsyth informed his command that the Lakota were to be taken to a military camp in Omaha, Nebraska.

The Massacre

The military was under orders to disarm those who were considered to be their prisoners, having escorted them to the camp-site the evening before. The Native Americans had elected to surrender without any attempt at resistance at that time. The military did not attempt to disarm their prisoners that evening. That morning, the Lakota were summoned to a meeting in their own camp, issued army hardtack for rations, and informed that they must hand over all firearms. Soldiers attempted to disarm the Lakota, but fears of hidden weapons persisted. Not satisfied with the weapons voluntarily stacked by the Lakota, the soldiers began to search the tents, and removed anything that could be used as a weapon. Seized material ranged from firearms to extra tent stakes and hatchets for cutting firewood. Next, the soldiers began to search the warriors themselves. As the efforts to locate weapons continued, the Lakota became more irritated and unruly according to US Army accounts.

The last warrior the soldiers attempted to disarm was Black Coyote. Some accounts claim that Black Coyote was deaf or otherwise impaired. Regardless, the seizure was unsuccessful and a weapon discharged. Fearing an attack, other soldiers on the rise began firing the Hotchkiss guns. Chaos ensued, as soldiers attempting to disarm Lakota warriors were caught in the crossfire, and warriors ran to re-arm themselves from the stacked weapons.

When the shooting stopped, 153 Lakota lay dead, along with 25 American cavalrymen. Big Foot lay among the dead. Perhaps a majority of the cavalrymen were killed by friendly fire, but no actual attempt was made to determine whether this was the case. The wounded soldiers and Native Americans were placed in wagons and taken to Pine Ridge. Approximately 50 Lakota arrived at Pine Ridge, but were kept outside in the cold until quarters were found. Approximately 150 Lakota remained unaccounted for. Most sources believe that these fled the federal army, and an unknown number subsequently died of wounds and exposure.

The Aftermath

The military hired civilians to bury the dead Lakota after an intervening snowstorm had abated. Arriving at the battleground, the burial party found the deceased frozen in contorted positions by the freezing weather. They were gathered up and placed in a common grave. Forsyth was exonerated by the US Army of any wrongdoing.

Reaction to the battle among the American public was generally favorable. Twenty Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded to federal soldiers. Currently, Native Americans are urgently seeking the recall of what they refer to as "Medals of Dis-Honor". Many non-natives living near the reservations interpreted the battle as a defeat of a murderous cult, though some confused Ghost Dancers with Native Americans in general. In an editorial in response to the event, a young newspaper editor, L. Frank Baum, later famous as the author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, wrote in the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer on January 3, 1891:

- The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extermination of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries, we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth. In this lies future safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past.

In the late 20th century, reaction grew more critical. Many consider the incident one of the most grievous atrocities in United States history. It has been commemorated in the popular protest song written by Buffy Sainte-Marie, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, as well as the book by historian Dee Brown by the same name.

Historically, Wounded Knee is generally considered to be the end of the Indian Wars, a series of conflicts between European colonial or U.S. forces and indigenous peoples since at least the 17th century, establishing total American dominance of the frontier. It was also responsible for the subsequent severe decline in the Ghost Dance movement.

More than eighty years after the massacre, beginning on February 27, 1973, Wounded Knee was also the site of a 71-day standoff between federal authorities and militants of the American Indian Movement.

Last armed conflict?

Strictly speaking, the Wounded Knee massacre was not the last armed conflict between Native Americans and the United States. A minor encounter at Drexel Mission one day after the Battle of Wounded Knee resulted in the death of one enlisted man, the wounding of six others, unknown Sioux casualties, as well as the death of Lieutenant James D. Mann of K Troop of the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment, from wounds received at Drexel Mission, some seventeen days later at Ft. Riley, Kansas on 15 January 1891, but this minor skirmish is often overlooked or combined into being a constituent part of the separate larger conflict, being almost totally overshadowed by the previous day's tragedy.

Further reading

- Coleman, William S.E. Voices of Wounded Knee, University of Nebraska Press (2000). ISBN 0803215061.

- Smith, Rex Alan. Moon of Popping Trees, University of Nebraska Press (1981). ISBN 0803291205.

- Utley, Robert. The Indian Frontier 1846-1890, University of New Mexico Press (2003). ISBN 0826329985.

- Yenne, Bill. Indian Wars: The Campaign for the American West, Westholme (2005). ISBN 1594160163.

- Brown, Dee. Bury my Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, Owl Books (1970). ISBN 0805066691.