Pioneer plaque: Difference between revisions

Kpufferfish (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

{{In popular culture|date=May 2010}} |

{{In popular culture|date=May 2010}} |

||

* In the science fiction film ''[[Star Trek V: The Final Frontier]]'', the plaque is shown attached to a ''Pioneer'' probe floating in space—just before the probe is intercepted and destroyed by a [[Klingon]] ship. In the ''Star Trek'' novel ''Federation'', a character mentions that humans had shown copies of the plaque to several alien races they encountered, but none had been able to decode it. |

* In the science fiction film ''[[Star Trek V: The Final Frontier]]'', the plaque is shown attached to a ''Pioneer'' probe floating in space—just before the probe is intercepted and destroyed by a [[Klingon]] ship. In the ''Star Trek'' novel ''Federation'', a character mentions that humans had shown copies of the plaque to several alien races they encountered, but none had been able to decode it. Conveniently, in the fictitious world of ''Star Trek'' and most other popular science fiction, all beings speak English and are thus able to easily explain their inability to decode the plaque. |

||

* An [[The Message (The Outer Limits)|episode]] of the science fiction series ''[[The Outer Limits (1995 TV series)|The Outer Limits]]'' featured a deaf woman receiving alien signals through her [[cochlear implant]], prompting her to write out Xs, 1s, and 0s on paper. When put together, the Xs turned into the images of man and woman from the plaque, along with an extraterrestrial humanoid raising a hand in a peaceful gesture. |

* An [[The Message (The Outer Limits)|episode]] of the science fiction series ''[[The Outer Limits (1995 TV series)|The Outer Limits]]'' featured a deaf woman receiving alien signals through her [[cochlear implant]], prompting her to write out Xs, 1s, and 0s on paper. When put together, the Xs turned into the images of man and woman from the plaque, along with an extraterrestrial humanoid raising a hand in a peaceful gesture. |

||

* In the promotion for the game, ''[[Battlezone II: Combat Commander|Battlezone II]]'', one of the ''Pioneer'' probes is seen drifting through space with the plaque visible on its side, although the text erroneously states that it is ''[[Voyager 2]]''. |

* In the promotion for the game, ''[[Battlezone II: Combat Commander|Battlezone II]]'', one of the ''Pioneer'' probes is seen drifting through space with the plaque visible on its side, although the text erroneously states that it is ''[[Voyager 2]]''. |

||

Revision as of 15:24, 11 August 2010

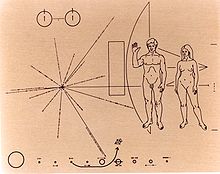

The Pioneer plaques are a pair of gold-anodized aluminum plaques which were placed on board the 1972 Pioneer 10 and 1973 Pioneer 11 spacecraft, featuring a pictorial message, in case either Pioneer 10 or 11 are intercepted by extraterrestrial life. The plaques show the nude figures of a human male and female along with several symbols that are designed to provide information about the origin of the spacecraft.[1]

The Pioneer spacecraft were the first human-built objects to leave the solar system. The plaques were attached to the spacecraft's antenna support struts in a position that would shield them from erosion by stellar dust.

The Voyager Golden Record, a much more complex and detailed message using (then) state-of-the-art media, was attached to the Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977.

History

The original idea, that the Pioneer spacecraft should carry a message from humankind, was first mentioned by Eric Burgess when he visited the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California during the Mariner 9 mission. He approached Carl Sagan, who had lectured about communication with extraterrestrial intelligences at a conference in Crimea.

Sagan was enthusiastic about the idea of sending a message with the Pioneer spacecraft. NASA agreed to the plan and gave him three weeks to prepare a message. Together with Frank Drake he designed the plaque, and the artwork was prepared by Sagan's then-wife Linda Salzman Sagan.

The first plaque was launched with Pioneer 10 on March 2, 1972, and the second followed with Pioneer 11 on April 5, 1973.

Physical properties

- Material: 6061 T6 gold-anodized aluminum

- Width: 229 mm (9 inches)

- Height: 152 mm (6 inches)

- Thickness: 1.27 mm (0.05 inches)

- Mean depth of engraving: 0.381 mm (0.015 inches)

- Mass: approx. 0.120 kilograms

Symbolism

Hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen

At the top left of the plate is a schematic representation of the hyperfine transition of hydrogen, which is the most abundant element in the universe. Below this symbol is a small vertical line to represent the binary digit 1. This spin-flip transition of a hydrogen atom from electron state spin up to electron state spin down can specify a unit of length (wavelength, 21 cm) as well as a unit of time (frequency, 1420 MHz). Both units are used as measurements in the other symbols.

Figures of a man and a woman

On the right side of the plaque, a man and a woman are shown in front of the spacecraft. Between the brackets that indicate the height of the woman, the binary representation of the number 8 can be seen (1000, with a small defect in the first zero). In units of the wavelength of the hyperfine transition of hydrogen this means 8 × 21 cm = 168 cm.

The right hand of the man is raised as a sign of good will. Although this gesture may not be understood, it offers a way to show the opposable thumb and how the limbs can be moved.

Originally Sagan drew the humans holding hands, but soon realized that an extraterrestrial might perceive the figure as a single creature rather than two organisms. The figures appear to be white and Occidental, but the generic depiction of humankind was intended to be as racially ambiguous as possible.

One can see that the woman's genitals are not really depicted; only the mons veneris is shown. It has been claimed that Sagan, having little time to complete the plaque, suspected that NASA would have rejected a more intricate drawing and therefore made a compromise just to be safe.[2] However, according to Mark Wolverton's more detailed account, the original design included a "short line indicating the woman's vulva."[3] It was erased as condition for approval by John Naugle, former head of NASA's Office of Space Science and the agency's former chief scientist.[4]

But Sagan himself wrote that "The decision to omit a very short line in this diagram was made partly because conventional representation in Greek statuary omits it. But there was another reason: Our desire to see the message successfully launched on Pioneer 10. In retrospect, we may have judged NASA's scientific-political hierarchy as more puritanical than it is. In the many discussions that I held with such officials up to the Administrator of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the President's Science Adviser, not one Victorian demurrer was ever voiced; and a great deal of helpful encouragement was given."

He also commented that "The idea of government censorship of the Pioneer 10 plaque is now so well documented and firmly entrenched that no statement from the designers of the plaque to the contrary can play any role in influencing the prevailing opinion. But we can at least try."[5]

Relative position of the Sun to the center of the Galaxy and 14 pulsars

The radial pattern on the left of the plaque shows 15 lines emanating from the same origin. Fourteen of the lines have corresponding long binary numbers, which stand for the periods of pulsars, using the hydrogen spin-flip transition frequency as the unit. Since these periods will change over time, the epoch of the launch can be calculated from these values.

The lengths of the lines show the relative distances of the pulsars to the Sun. A tick mark at the end of each line gives the Z coordinate perpendicular to the galactic plane.

If the plaque is found, only some of the pulsars may be visible from the location of its discovery. Showing the location with as many as 14 pulsars provides redundancy so that the location of the origin can be triangulated even if only some of the pulsars are recognized.

The data for one of the pulsars is misleading. When the plaque was designed, the frequency of pulsar "1240" (now known as J1243-6423) was known to only three significant decimal digits: 0.388 seconds.[1] The map lists the period of this pulsar in binary to much greater precision: 100000110110010110001001111000. Rounding this off at about 10 significant bits (100000110100000000000000000000) would have provided a hint of this uncertainty. This pulsar is represented by the long line pointing down and to the right.

The fifteenth line on the plaque extends to the far right, behind the human figures. This line indicates the sun's relative distance to the center of the galaxy.

The pulsar map and hydrogen molecule diagram are shared in common with the Voyager Golden Record.

Solar system

At the bottom of the plaque is a schematic diagram of the solar system. A small picture of the spacecraft is shown, and the trajectory shows its way past Jupiter and out of the solar system. Both Pioneers 10 and 11 have identical plaques; however, after launch, Pioneer 11 was redirected towards Saturn and from there it exited the solar system. In this regard the Pioneer 11 plaque is somewhat inaccurate. The Saturn flyby of Pioneer 11 would also greatly influence its future direction and destination as compared to Pioneer 10 but this fact is not depicted in the plaques.

Saturn's rings could give a further hint to identifying the solar system. Rings around the planets Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune were unknown when the plaque was designed, however unlike Saturn the ring systems on these planets are not as easily visible and apparent as Saturn's. Pluto was considered to be a planet when the plaque was designed; in 2006 the IAU reclassified Pluto as a dwarf planet and then in 2008 as a plutoid. Other large bodies classed as dwarf planets, such as Sedna, are not depicted as they were unknown at the time the plaque was made.

The binary numbers next to the planets show the relative distance to the sun. The unit is 1/10 of Mercury's orbit.

Silhouette of the spacecraft

Behind the figures of the human beings, the silhouette of the Pioneer spacecraft is shown in the same scale so that the size of the human beings can be deduced by measuring the spacecraft.

Criticism

This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (January 2010) |

One of the parts of the diagram that is among the easiest for humans to understand may be among the hardest for the extraterrestrial finders to understand: the arrow showing the trajectory of Pioneer. An article in Scientific American[6] criticized the use of an arrow because arrows are an artifact of hunter-gatherer societies like those on Earth; finders with a different cultural heritage may find the arrow symbol meaningless.

According to astronomer Frank Drake, there were many negative reactions to the plaque because the human beings were displayed naked.[7] The Chicago Sun-Times retouched its image to hide the genitals of the man and woman.

In popular culture

- In the science fiction film Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, the plaque is shown attached to a Pioneer probe floating in space—just before the probe is intercepted and destroyed by a Klingon ship. In the Star Trek novel Federation, a character mentions that humans had shown copies of the plaque to several alien races they encountered, but none had been able to decode it. Conveniently, in the fictitious world of Star Trek and most other popular science fiction, all beings speak English and are thus able to easily explain their inability to decode the plaque.

- An episode of the science fiction series The Outer Limits featured a deaf woman receiving alien signals through her cochlear implant, prompting her to write out Xs, 1s, and 0s on paper. When put together, the Xs turned into the images of man and woman from the plaque, along with an extraterrestrial humanoid raising a hand in a peaceful gesture.

- In the promotion for the game, Battlezone II, one of the Pioneer probes is seen drifting through space with the plaque visible on its side, although the text erroneously states that it is Voyager 2.

- The plaque appeared on the cover of the 1992 album Yareakh (Template:Lang-he, Moon) by Israeli singer Shlomo Artzi.

- The cover of the album Sideshow Symphonies by the Norwegian Avant-garde metal band Arcturus is based on the design of the plaque.

- On her album United States Live, American performance artist Laurie Anderson contemplates extraterrestrials finding the plaque and asks "do you think that they will think his arm is permanently attached in this position?"

- In an episode of the animated television series Futurama, Bender the robot is accidentally fired into space from the ship's torpedo tube, leaving him to drift through the cosmos forever. Bender scratches a drawing resembling the Pioneer plaque onto his chest with a giant depiction of himself threatening the man and woman. He then remarks, "There! Now when I'm found in a million years people will know what the score was."

See also

- Alien language

- Communication with Extraterrestrial Intelligence

- Pioneer program

- Voyager Golden Record

References

- ^ a b "A Message from Earth" (PDF). Science. 175: 881–884. 1972-02-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) Paper on the background of the plaque. Pages available online: 1, 2, 3, 4 - ^ Alan Fletcher, "The art of looking sideways" Phaidon Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7148-3449-1

- ^ Mark Wolverton, The Depths of Space: The Story of the Pioneer Planetary Probes, Joseph Henry Press, 2004, p. 79. ISBN 0-309-09050-4.

- ^ Wolverton, supra., p. 80.

- ^ Carl Sagan, Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-78303-8, pages 22-25

- ^ Ernst Gombrich ‘The Visual Image’, 1972 in Scientific American (eds)Communication. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, pp. 46–60; originally in a special issue of Scientific American, September 1972; republished in Gombrich (1982) The Image and the Eye: Further Studies in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation. London: Phaidon, pp. 137–61.

- ^ Cited in Carl Sagan: Murmurs of Earth, 1978, New York, ISBN 0-679-74444-4

External links

- NASA on the plaque

- NASA on Pioneer 10 & 11

- The Pioneer Plaque as depicted in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier

- Abhijit Bhattacharjee A suggestion to choose the balanced ternary number system on the plaque as a universally deducible number system for future plaques

- Reading the Pioneer/Voyager Pulsar Map (Wm. Robert Johnston), updated 11 March 2003. Last accessed on 8 April 2006

- Edward Tufte, Pioneer Space Plaque Redesign. A humorous critique of the plaque's design

- Communicating with Aliens - An analysis of the chances of an alien civilisation being able to decipher the Pioneer plaque.