Ginger Rogers: Difference between revisions

→Portrayals of Rogers: film |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

[[Image:fredginger.jpg|thumb|left|Ginger with [[Fred Astaire]] in the film ''[[Roberta (1935 film)|Roberta]]'' (1935).]] |

[[Image:fredginger.jpg|thumb|left|Ginger with [[Fred Astaire]] in the film ''[[Roberta (1935 film)|Roberta]]'' (1935).]] |

||

Although the dance routines were choreographed by Astaire and his collaborator [[Hermes Pan (choreographer)|Hermes Pan]], both have acknowledged Rogers' input and have also testified to her consummate professionalism, even during periods of intense strain, as she tried to juggle her many other contractual film commitments with the punishing rehearsal schedules of Astaire, who made at most two films in any one year. In 1986, shortly before his death, Astaire remarked, "All the girls I ever danced with thought they couldn't do it, but of course they could. So they always cried. All except Ginger. No no, Ginger never cried". John Mueller summed up Rogers' abilities as follows: "Rogers was outstanding among Astaire's partners not because she was superior to others as a dancer but because, as a skilled, intuitive actress, she was cagey enough to realize that acting did not stop when dancing began...the reason so many women have fantasized about dancing with Fred Astaire is that Ginger Rogers conveyed the impression that dancing with him is the most thrilling experience imaginable". According to Astaire, when they were first teamed together in "Flying Down to Rio", "Ginger had never danced with a partner before. She faked it an awful lot. She couldn't tap and she couldn't do this and that ... but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got so that after a while everyone else who danced with me looked wrong." |

Although the dance routines were choreographed by Astaire and his collaborator [[Hermes Pan (choreographer)|Hermes Pan]], both have acknowledged Rogers' input and have also testified to her consummate professionalism, even during periods of intense strain, as she tried to juggle her many other contractual film commitments with the punishing rehearsal schedules of Astaire, who made at most two films in any one year. In 1986, shortly before his death, Astaire remarked, "All the girls I ever danced with thought they couldn't do it, but of course they could. So they always cried. All except Ginger. No no, Ginger never cried". John Mueller summed up Rogers' abilities as follows: "Rogers was outstanding among Astaire's partners not because she was superior to others as a dancer but because, as a skilled, intuitive actress, she was cagey enough to realize that acting did not stop when dancing began...the reason so many women have fantasized about dancing with Fred Astaire is that Ginger Rogers conveyed the impression that dancing with him is the most thrilling experience imaginable". According to Astaire, when they were first teamed together in "Flying Down to Rio", "Ginger had never danced with a partner before. She faked it an awful lot. She couldn't tap and she couldn't do this and that ... but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got so that after a while everyone else who danced with me looked wrong." Rogers was the Texas State Champion Charleston Winner. Astaire also had this to say to Raymond Rohauer, curator at the New York Gallery of Modern Art, "Ginger was brilliantly effective. She made everything work for her. Actually she made things very fine for both of us and she deserves most of the credit for our success." |

||

Rogers also introduced some celebrated numbers from the [[Great American Songbook]], songs such as [[Harry Warren]] and [[Al Dubin]]'s "[[The Gold Diggers' Song (We're in the Money)]]" from ''[[Gold Diggers of 1933]]'' (1933), "Music Makes Me" from ''[[Flying Down to Rio]]'' (1933), "[[The Continental]]" from ''[[The Gay Divorcee]]'' (1934), [[Irving Berlin]]'s "[[Let Yourself Go]]" from ''Follow the Fleet'' (1936) and [[George Gershwin|the Gershwins']] "[[Embraceable You]]" from ''[[Girl Crazy]]'' and "[[They All Laughed (song)|They All Laughed (at Christopher Columbus)]]" from ''[[Shall We Dance (1937 film)|Shall We Dance]]'' (1937). Furthermore, in song duets with Astaire, she co-introduced Berlin's "[[I'm Putting all My Eggs in One Basket]]" from ''Follow the Fleet'' (1936), [[Jerome Kern]] and [[Dorothy Fields]]'s "[[Pick Yourself Up]]" and "[[A Fine Romance (song)|A Fine Romance]]" from ''[[Swing Time]]'' (1936) and the Gershwins' "[[Let's Call the Whole Thing Off]]" from ''[[Shall We Dance (1937 film)|Shall We Dance]]'' (1937). |

Rogers also introduced some celebrated numbers from the [[Great American Songbook]], songs such as [[Harry Warren]] and [[Al Dubin]]'s "[[The Gold Diggers' Song (We're in the Money)]]" from ''[[Gold Diggers of 1933]]'' (1933), "Music Makes Me" from ''[[Flying Down to Rio]]'' (1933), "[[The Continental]]" from ''[[The Gay Divorcee]]'' (1934), [[Irving Berlin]]'s "[[Let Yourself Go]]" from ''Follow the Fleet'' (1936) and [[George Gershwin|the Gershwins']] "[[Embraceable You]]" from ''[[Girl Crazy]]'' and "[[They All Laughed (song)|They All Laughed (at Christopher Columbus)]]" from ''[[Shall We Dance (1937 film)|Shall We Dance]]'' (1937). Furthermore, in song duets with Astaire, she co-introduced Berlin's "[[I'm Putting all My Eggs in One Basket]]" from ''Follow the Fleet'' (1936), [[Jerome Kern]] and [[Dorothy Fields]]'s "[[Pick Yourself Up]]" and "[[A Fine Romance (song)|A Fine Romance]]" from ''[[Swing Time]]'' (1936) and the Gershwins' "[[Let's Call the Whole Thing Off]]" from ''[[Shall We Dance (1937 film)|Shall We Dance]]'' (1937). |

||

Revision as of 08:01, 27 August 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

Ginger Rogers | |

|---|---|

in Stage Door (1937) | |

| Born | Virginia Katherine McMath |

| Occupation(s) | Actress, singer, dancer, artist |

| Years active | 1929–1994 |

| Spouse(s) | Jack Pepper (1929–1931) Lew Ayres (1934–1941) Jack Briggs (1943–1949) Jacques Bergerac (1953–1957) William Marshall (1961–1969) |

Ginger Rogers (July 16, 1911 – April 25, 1995) was an American stage actress, dancer, and singer who appeared in film, radio, and television throughout much of the 20th century.

During her long career, she made a total of 73 films, and is noted for her role as Fred Astaire's romantic interest and dancing partner in a series of ten Hollywood musical films that revolutionized the genre. She also achieved success in a variety of film roles, and won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Kitty Foyle (1940).

She ranks #14 on the AFI's 100 Years... 100 Stars list of actresses.

Early life

Rogers was born Virginia Katherine McMath in Independence, Missouri, the daughter of William Eddins McMath, an electrical engineer, and his wife Lela Emogene Owens (1891–1977).[1] Ginger's parents separated soon after her birth, and she and her mother went to live with her grandparents, Walter and Saphrona (née Ball) Owens, in nearby Kansas City. Rogers' parents fought over her custody, with her father even kidnapping her twice. After the parents divorced, Rogers stayed with her grandparents while her mother wrote scripts for two years in Hollywood.

Rogers was to remain close to her grandfather (much later, when she was already a star in 1939, she bought him a home at 5115 Greenbush Avenue in Sherman Oaks, California so that he could be close to her while she was filming at the studios).

One of Rogers' young cousins, Helen, had a hard time pronouncing her first name, shortening it to "Ginga"; the nickname stuck.

When Rogers was nine years old, her mother married John Logan Rogers. Ginger took the name of Rogers, though she was never legally adopted. They lived in Fort Worth, Texas. Her mother became a theater critic for a local newspaper, the Fort Worth Record. Ginger attended but did not graduate from Fort Worth's Central High School.

As a teenager, Rogers thought of becoming a schoolteacher, but with her mother's interest in Hollywood and the theater, her early exposure to the theater increased. Waiting for her mother in the wings of the Majestic Theatre, she began to sing and dance along to the performers on stage.

Vaudeville and Broadway

Rogers' entertainment career was born one night when the traveling vaudeville act of Eddie Foy came to Fort Worth and needed a quick stand-in. She then entered and won a Charleston dance contest which allowed her to tour for six months, at one point in 1926 performing at an 18-month old theater called The Craterian in Medford, Oregon. This theater honored her many years later by changing its name to the Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater.[2]

At 17, Rogers married Jack Culpepper, a singer/dancer/comedian/recording artist of the day who worked under the name Jack Pepper (according to Ginger's autobiography, she knew Culpepper when she was a child, as her cousin's boyfriend). They formed a short-lived vaudeville double act known as "Ginger and Pepper". The marriage was over within months, and she went back to touring with her mother. When the tour got to New York City, she stayed, getting radio singing jobs and then her Broadway theater debut in a musical called Top Speed, which opened on Christmas Day, 1929.

Within two weeks of opening in Top Speed, Rogers was chosen to star on Broadway in Girl Crazy by George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin, the musical play widely considered to have made stars of both Ginger and Ethel Merman. Fred Astaire was hired to help the dancers with their choreography. Her appearance in Girl Crazy made her an overnight star at the age of 19. In 1930, she was signed by Paramount Pictures to a seven-year contract.

Film career

1929-1933

Rogers' first movie roles were in a trio of short films made in 1929—Night in the Dormitory, A Day of a Man of Affairs, and Campus Sweethearts.

Rogers would soon get herself out of the Paramount contract—under which she had made five feature films at Astoria Studios in Astoria, Queens—and move with her mother to Hollywood. When she got to California, she signed a three-picture deal with Pathé. She made feature films for Warner Bros., Monogram, and Fox in 1932 and was named one of fifteen "WAMPAS Baby Stars". She then made a significant breakthrough as "Anytime Annie" in the Warner Brothers film 42nd Street (1933). She went on to make a series of films with Fox, Warner Bros. ("Gold Diggers of 1933"), Universal, Paramount, and RKO Radio Pictures and, in her second RKO picture, Flying Down to Rio (1933), she worked for the first time with Fred Astaire.

1933-1939: Astaire and Rogers

Rogers was most famous for her partnership with Fred Astaire. Together, from 1933 to 1939, they made ten musical films at RKO: Flying Down to Rio (1933), The Gay Divorcee (1934), Roberta (1935), Top Hat (1935), Follow the Fleet (1936), Swing Time (1936), Shall We Dance (1937), Carefree (1938), and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939) (The Barkleys of Broadway (1949) was produced later at MGM). They revolutionized the Hollywood musical, introducing dance routines of unprecedented elegance and virtuosity, set to songs specially composed for them by the greatest popular song composers of the day.

Arlene Croce, Hannah Hyam and John Mueller all consider Rogers to have been Astaire's finest dance partner, principally due to her ability to combine dancing skills, natural beauty and exceptional abilities as a dramatic actress and comedienne, thus truly complementing Astaire: a peerless dancer who sometimes struggled as an actor and was not considered classically handsome. The resulting song and dance partnership enjoyed a unique credibility in the eyes of audiences. Of the 33 partnered dances she performed with Astaire, Croce and Mueller have highlighted the infectious spontaneity of her performances in the comic numbers "I'll Be Hard to Handle" from Roberta (1935), "I'm Putting all My Eggs in One Basket" from Follow the Fleet (1936) and "Pick Yourself Up" from Swing Time (1936). They also point to the use Astaire made of her remarkably flexible back in classic romantic dances such as "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" from Roberta (1935), "Cheek to Cheek" from Top Hat (1935) and "Let's Face the Music and Dance" from Follow the Fleet (1936). For special praise, they have singled out her performance in the "Waltz in Swing Time" from Swing Time (1936), which is generally considered to be the most virtuosic partnered routine ever committed to film by Astaire. She generally avoided solo dance performances: Astaire always included at least one virtuoso solo routine in each film, while Rogers performed only one: "Let Yourself Go" from Follow the Fleet (1936).

Although the dance routines were choreographed by Astaire and his collaborator Hermes Pan, both have acknowledged Rogers' input and have also testified to her consummate professionalism, even during periods of intense strain, as she tried to juggle her many other contractual film commitments with the punishing rehearsal schedules of Astaire, who made at most two films in any one year. In 1986, shortly before his death, Astaire remarked, "All the girls I ever danced with thought they couldn't do it, but of course they could. So they always cried. All except Ginger. No no, Ginger never cried". John Mueller summed up Rogers' abilities as follows: "Rogers was outstanding among Astaire's partners not because she was superior to others as a dancer but because, as a skilled, intuitive actress, she was cagey enough to realize that acting did not stop when dancing began...the reason so many women have fantasized about dancing with Fred Astaire is that Ginger Rogers conveyed the impression that dancing with him is the most thrilling experience imaginable". According to Astaire, when they were first teamed together in "Flying Down to Rio", "Ginger had never danced with a partner before. She faked it an awful lot. She couldn't tap and she couldn't do this and that ... but Ginger had style and talent and improved as she went along. She got so that after a while everyone else who danced with me looked wrong." Rogers was the Texas State Champion Charleston Winner. Astaire also had this to say to Raymond Rohauer, curator at the New York Gallery of Modern Art, "Ginger was brilliantly effective. She made everything work for her. Actually she made things very fine for both of us and she deserves most of the credit for our success."

Rogers also introduced some celebrated numbers from the Great American Songbook, songs such as Harry Warren and Al Dubin's "The Gold Diggers' Song (We're in the Money)" from Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), "Music Makes Me" from Flying Down to Rio (1933), "The Continental" from The Gay Divorcee (1934), Irving Berlin's "Let Yourself Go" from Follow the Fleet (1936) and the Gershwins' "Embraceable You" from Girl Crazy and "They All Laughed (at Christopher Columbus)" from Shall We Dance (1937). Furthermore, in song duets with Astaire, she co-introduced Berlin's "I'm Putting all My Eggs in One Basket" from Follow the Fleet (1936), Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields's "Pick Yourself Up" and "A Fine Romance" from Swing Time (1936) and the Gershwins' "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" from Shall We Dance (1937).

After 1939

After 15 months apart and with RKO facing bankruptcy, the studio hired Fred and Ginger for another movie called Carefree, but it lost money. Next came The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle, but the serious plot and tragic ending resulted in the worst box office receipts of any of their films. This was driven, not by diminished popularity, but by the hard 1930s economic reality. The production costs of musicals, always significantly more costly than regular features, continued to increase at a much faster rate than admissions. Everyone agreed it was time to stop.

Both before and immediately after her great dancing and acting partnership with Fred Astaire ended, Rogers, now on her own and one of the highest paid actresses in Hollywood, starred in more than a few very successful dramas and comedies. Stage Door (1937) demonstrated her skillful dramatic capacity, as the loquacious yet vulnerable girl next door, a tough minded, theatrical hopeful, opposite Katharine Hepburn. In Roxie Hart (1942), which served as the template for the 2002 production of Chicago, Ginger played a wise-cracking wife on trial for a murder her husband committed. In the neo-realist Primrose Path (1940), directed by Gregory La Cava, she played a prostitute's daughter trying to avoid the fate of her mother. Further highlights of this period included Tom, Dick, and Harry, a pleasing 1941 comedy where she dreams of marrying three different men; I'll Be Seeing You, an intelligent and restrained war time "weepie" with Joseph Cotten; La Cava's 5th Avenue Girl (1939), where she played an out-of-work girl sucked into the lives of a wealthy family; and especially the sharp and highly successful comedies: Bachelor Mother (1939), where she played Polly Parrish, a shop girl who is falsely deemed to have abandoned her baby; and Billy Wilder's first feature film: The Major and the Minor (1942), where she played herself as a 12-year-old, at her own real age, and pretended to be her own mother. Her greatest skills were as a comedienne, and, as a master of the deadpan and the sidelong glance, she became well established as one of the major actresses of the screwball comedy era.

In 1941, Ginger Rogers won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her starring role in 1940's Kitty Foyle. She enjoyed considerable success during the early 1940s, and was RKO's hottest property during this period. Becoming a free agent, she made hugely successful films with other studios in the mid-'40s, including "Tender Comrade" (1943), "Lady in the Dark" (1944), and "Week-End at the Waldorf" (1945), and became the highest-paid performer in Hollywood. However, by the end of the decade, her film career had peaked. Arthur Freed reunited her with Fred Astaire in The Barkleys of Broadway in 1949, a delightful Technicolor MGM musical which succeeded in rekindling the special chemistry between them one last time.

Ginger Rogers' film career entered a period of gradual decline in the 1950s, as parts for older actresses became more difficult to obtain, but she still scored with some solid films. She starred in Storm Warning (1950), with Ronald Reagan and Doris Day, the noir, anti Ku Klux Klan film by Warner Brothers, and in Monkey Business (1952), with Cary Grant and Marilyn Monroe, directed by Howard Hawks. In the same year, she also starred in We're Not Married!, also featuring Marilyn Monroe, and in Dreamboat. She played the female lead in Tight Spot (1955), a mystery thriller, with Edward G. Robinson. Then, after a series of unremarkable films, she scored with a great popular success, playing Dolly Levi in the long running Hello, Dolly! on Broadway in 1965.

In later life, Rogers remained on good terms with Astaire: she presented him with a special Academy Award in 1950, and they were co-presenters of individual Academy Awards in 1967, during which they elicited a standing ovation when they came on stage in an impromptu dance. In 1969, she had the lead role in another long running popular production of Mame, from the book by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, with music and lyrics by Jerry Herman, at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in the West End of London, arriving for the role on the Liner QE2 from New York. Her docking there occasioned the maximum of pomp and ceremony at Southampton. She became the highest paid performer in the history of the West End up to that time. The production ran for 14 months and featured a Royal Command Performance for Queen Elizabeth the Second. The Kennedy Center honored Ginger Rogers in December 1992. This event, which was shown on television, was somewhat marred when Astaire's widow, Robyn Smith, who permitted clips of Astaire dancing with Rogers to be shown for free at the function itself, was unable to come to terms with CBS Television for broadcast rights to the clips (all previous rights holders having donated broadcast rights gratis).[3]

From the 1950s onwards, Rogers would make occasional appearances on television. In the later years of her career, she made guest appearances in three different series by Aaron Spelling; The Love Boat (1979), Glitter (1984), and Hotel (1987) which would be her final screen appearance as an actress.

Personal life

Rogers was an only child, and maintained a close relationship with her mother throughout her life. Lela Rogers (1891–1977), was a newspaper reporter, scriptwriter, and movie producer. She was also one of the first women to enlist in the Marine Corps, founded the successful "Hollywood Playhouse", for aspiring actors and actresses on the RKO set, and was a founder of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals. Mother and daughter had an extremely close professional relationship as well. Lela Rogers was credited with many pivotal contributions to her daughter's early successes in New York and in Hollywood, not to mention contract negotiations with R.K.O.

In her classic 1930s musicals with Astaire, Ginger Rogers not only was paid less than Fred (who also received 10% of the profits), but also less than many of the supporting "farceurs". This in spite of her pivotal role in the films' financial success. This was personally very grating and insulting to her, and had an effect upon her relationships at RKO, especially with director Mark Sandrich (whose denigration of Rogers prompted the famous sharp letter of reprimand from producer Pandro Berman to Sandrich, which Rogers deemed important enough to publish in her autobiography). Like many actresses of the time, Ginger Rogers fought hard for her contract and salary rights, and for better films and scripts. She also found it necessary to fight for respect and dignity as an actress, and against the type casting as just a "dancing girl" that came with the territory in the studio system of the era. She succeeded in all these endeavors.

Rogers' first marriage was to her dancing partner Jack Pepper (real name Edward Jackson Culpepper) on March 29, 1929. They divorced in 1931, having separated soon after the wedding. She married again in 1934 to actor Lew Ayres (1908–1996). At a time when Rogers' career was skyrocketing and Ayres' career was faltering, they separated and were amicably divorced (to Rogers' ongoing regret) seven years later. To add to Roger's woes in 1934, Rogers sued Sylvia of Hollywood for a $100K defamation suit. Sylvia, Hollywood's fitness guru and radio personality, had claimed that Rogers was on Sylvia’s radio show when, in fact, she was not.[4]

In 1940, Rogers purchased a 1000-acre (4 km²) ranch in Jackson County, Oregon between the cities of Shady Cove and Eagle Point. The ranch, located along the Rogue River, supplied dairy products to nearby Camp White, a cantonment established for the duration of World War II. While not performing or working on other projects, she would live at the ranch with her mother.

In 1943, Rogers married her third husband, Jack Briggs, a Marine. Upon his return from World War II, Briggs showed no interest in continuing his incipient Hollywood career. They divorced in 1949. She married once again in 1953, a Frenchman, Jacques Bergerac, 16 years her junior, whom she met on a trip to Paris. A lawyer in France, he came to Hollywood with her and became an actor. They divorced in 1957. Her fifth and final husband was director and producer William Marshall. They married in 1961, and divorced in 1971, after his bouts with alcohol, and the financial collapse of their joint film production company in Jamaica.

Rogers was good friends with Lucille Ball — a distant cousin on Rogers' mother's side — for many years until Ball's death in 1989, at the age of 77. Another friend, Bette Davis, had in common with Rogers a close maternal relationship. As early Hollywood feminists, all three shared a common interest in directing and producing. In fact, Ginger Rogers starred in one of the earliest films co-directed and co-scripted by a woman: Wanda Tuchock's Finishing School in 1934. In 1985, Rogers fulfilled a long-standing wish to direct by directing the musical Babes in Arms off-Broadway in Tarrytown, New York, when she was 74 years old. She appeared with Lucille Ball in an episode of Here's Lucy on November 22, 1971, where, with Lucie Arnaz, Rogers gave a demonstration of the Charleston in her famous "high heels".

Rogers maintained a close friendship with her cousin, actress/writer/socialite Phyllis Fraser (whom she aided in a brief acting career), but was not Rita Hayworth's natural cousin as has been reported. Hayworth's maternal uncle, Vinton Hayworth, was married to Rogers' maternal aunt, Jean Owens.

In 1977, Rogers' mother died. Rogers remained at the 4-Rs (Rogers's Rogue River Ranch) until 1990, when she sold the property and moved to nearby Medford, Oregon. Her last public appearance was on March 18, 1995 when she received the Women's International Center (WIC) Living Legacy Award.[5]

For many years, Rogers regularly supported, and held in-person presentations, at the Craterian Theater, in Medford, Oregon, where she had performed in 1926 as a vaudevillian. The theater was comprehensively restored in 1997, and posthumously renamed in her honor, as the Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater.

Rogers would spend winters in Rancho Mirage and summers in Medford. She died in Rancho Mirage on April 25, 1995 of congestive heart failure at the age of 83. She was cremated; her ashes are interred in the Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, California, with Lela's, and just a short distance from the grave of Fred Astaire.

She was a lifelong member of the Republican Party[6].

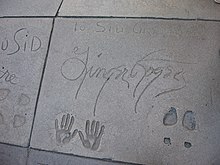

Portrayals of Rogers

No films have been made about Ginger Rogers, most likely because Fred Astaire stipulated in his will that no film representations of him were to ever be made. As Rogers' career history is inevitably linked to Astaire, it is unlikely an accurate portrayal could easily be made of her on film.

- No portrayal was made of her in The Aviator (2004), in spite of the fact that many of her fellow actresses who, like her, dated Howard Hughes, were portrayed. According to Rogers' autobiography Ginger: My Story, published in 1991, Hughes was very intent on marrying her, and had proposed to her, until she discovered his infidelity and broke off the engagement.

- Likenesses of Astaire and Rogers, apparently painted over from the Cheek to Cheek dance in Top Hat, are in the Lucy in the Skies section of The Beatles film Yellow Submarine (1968).

- Rogers' image is one of many famous woman's images, of the 1930s and 1940s, to feature on the bedroom wall in the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, a gallery of magazine cuttings, pasted on to the wall and created by Anne and her sister Margot while hiding from the Nazis. When the house became a museum, the gallery the Frank sisters created was preserved under glass. Rogers' image is one of the larger and more prominent, which clearly indicates her global and mass appeal amongst the young of the time.

- A musical about the life of Rogers, entitled Backwards in High Heels, premiered in Florida in early 2007.[7][8]

- Rogers was the heroine of a novel, Ginger Rogers and the Riddle of the Scarlet Cloak (1942, by Lela E. Rogers), where "the heroine has the same name and appearance as the famous actress but has no connection ... it is as though the famous actress has stepped into an alternate reality in which she is an ordinary person." The story was probably written for a young teenage audience and is reminiscent of the adventures of Nancy Drew. It is part of a series known as "Whitman Authorized Editions", 16 books published between 1941-1947 that featured a film actress as heroine.[9]

Filmography

Features

- Young Man of Manhattan (1930)

- The Sap from Syracuse (1930)

- Queen High (1930)

- Follow the Leader (1930)

- Honor Among Lovers (1931)

- The Tip-Off (1931)

- Suicide Fleet (1931)

- Carnival Boat (1932)

- The Tenderfoot (1932)

- The Thirteenth Guest (1932)

- Hat Check Girl (1932)

- You Said a Mouthful (1932)

- Broadway Bad (1933)

- 42nd Street (1933)

- Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933)

- Professional Sweetheart (1933)

- Don't Bet on Love (1933)

- A Shriek in the Night (1933)

- Rafter Romance (1933)

- Chance at Heaven (1933)

- Sitting Pretty (1933)

- Flying Down to Rio (1933) (*)

- Twenty Million Sweethearts (1934)

- Upperworld (1934)

- Finishing School (1934)

- Change of Heart (1934)

- The Gay Divorcee (1934) (*)

- Romance in Manhattan (1935)

- Roberta (1935) (*)

- Star of Midnight (1935)

- Top Hat (1935) (*)

- In Person (1935)

- Follow the Fleet (1936) (*)

- Swing Time (1936) (*)

- Shall We Dance (1937) (*)

- Stage Door (1937)

- Vivacious Lady (1938)

- Having Wonderful Time (1938)

- Carefree (1938) (*)

- The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939) (*)

- Bachelor Mother (1939)

- 5th Ave Girl (1939)

- Primrose Path (1940)

- Lucky Partners (1940)

- Kitty Foyle (1940)

- Tom, Dick and Harry (1941)

- Roxie Hart (1942)

- Tales of Manhattan (1942)

- The Major and the Minor (1942)

- Once Upon a Honeymoon (1942)

- Tender Comrade (1943)

- Lady in the Dark (1944)

- I'll Be Seeing You (1944)

- Week-End at the Waldorf (1945)

- Heartbeat (1946)

- Magnificent Doll (1947)

- It Had to Be You (1947)

- The Barkleys of Broadway (1949) (*)

- Perfect Stranger (1950)

- Storm Warning (1951)

- The Groom Wore Spurs (1951)

- We're Not Married! (1952)

- Dreamboat (1952)

- Monkey Business (1952)

- Forever Female (1953)

- Twist of Fate (1954)

- Black Widow (1954)

- Tight Spot (1955)

- The First Traveling Saleslady (1956)

- Teenage Rebel (1956)

- Oh, Men! Oh, Women! (1957)

- The Confession, aka Quick, Let's Get Married and Seven Different Ways (1964)

- Harlow (1965)

- Cinderella: Rodgers and Hammerstein Version (1965)

- George Stevens: A Filmmaker's Journey (1984)

(*): performances with Fred Astaire

Short subjects

- A Day of a Man of Affairs (1929)

- A Night in a Dormitory (1930)

- Campus Sweethearts (1930)

- Office Blues (1930)

- Hollywood on Parade (1932)

- Screen Snapshots (1932)

- Hollywood on Parade No. A-9 (1933)

- Hollywood Newsreel (1934)

- Screen Snapshots Series 16, No. 3 (1936)

- Show Business at War (1943)

- Battle Stations (Narrator, 1944)

- Screen Snapshots: The Great Showman (1950)

- Screen Snapshots: Hollywood's Great Entertainers (1954)

Television

- The DuPont Show with June Allyson, as Kay Neilson in "The Tender Shoot" (October 18, 1959)

- What's My Line? (1954, 1957, 1963)

- Cinderella (1965)

- The Love Boat (1979) (episodes 3.10 and 3.11)

- Glitter (1984) (episode 1.3)

- Hotel (1987) (episode 5.1) (final screen role)

References

- ^ Notable American women: a biographical dictionary completing the twentieth ... By Susan Ware

- ^ "Facility History". Craterian Ginger Rogers Theater. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ Wharton, Dennis (1992-12-18). "Astaire footage withheld from Honors". Variety (magazine). Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ Interview Suit Begun By Actress: Screen Player Asks Damages, Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1934.

- ^ Biography Women's International Center. Retrieved 2009-10-20.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/enwiki/w/index.php?title=Helen_Hayes&action=edit§ion=3

- ^ Playbill News: Sold Out Florida Stage Run of Ginger Rogers Musical Gets Added Performances

- ^ Backwards in High Heels: The Ginger Musical

- ^ Whitman Authorized Editions for Girls, accessed September 10, 2009

Bibliography

- Fred Astaire: Steps in Time, 1959, multiple reprints.

- Arlene Croce: The Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers Book, Galahad Books 1974, ISBN 0-88365-099-1

- Jocelyn Faris: Ginger Rogers - a Bio-Bibliography, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1994, ISBN 0-313-29177-2

- Hannah Hyam: Fred and Ginger - The Astaire-Rogers Partnership 1934-1938, Pen Press Publications, Brighton, 2007. ISBN 978-1-905621-96-5

- John Mueller: Astaire Dancing - The Musical Films of Fred Astaire, Knopf 1985, ISBN 0-394-51654-0

- Ginger Rogers: Ginger My Story, New York: Harper Collins, 1991

External links

- Please use a more specific IMDb template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Ginger Rogers at the TCM Movie Database

- Please use a more specific IBDB template. See the documentation for available templates.

- Fred Astaire (1986 archive footage), The 100 Greatest Musicals, Channel 4 television, 2003

- Backwards in High Heels: The Ginger Musical

- Ginger Rogers biography from Reel Classics

- John Mueller's 1991 New York Times review of Ginger: My Story

- Ginger Rogers at Find a Grave

- 1911 births

- 1995 deaths

- People from Independence, Missouri

- Missouri Republicans

- American musicians of Scottish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American Christian Scientists

- American ballroom dancers

- American film actors

- American tap dancers

- Best Actress Academy Award winners

- Cardiovascular disease deaths in California

- Deaths from congestive heart failure

- Republicans (United States)

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Traditional pop music singers

- 20th-century actors

- Vaudeville performers

- California Republicans

- Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery burials

- People from Eagle Point, Oregon

- People from Jackson County, Oregon