Bassoon: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 388893616 by 182.4.73.97 (talk) |

etdaednesse Tag: blanking |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Circumstantial evidence indicates that the baroque bassoon was a newly invented instrument, rather than a simple modification of the old dulcian. The dulcian was not immediately supplanted, but continued to be used well into the 18th century by [[Johann Sebastian Bach|Bach]] and others. The man most likely responsible for developing the true bassoon was Martin Hotteterre (d.1712), who may also have invented the three-piece ''flûte traversière'' and the [[Oboe#Baroque|''hautbois'']]. Some historians believe that sometime in the 1650s, Hotteterre conceived the bassoon in four sections (bell, bass joint, boot and wing joint), an arrangement that allowed greater accuracy in machining the bore compared to the one-piece dulcian. He also extended the compass down to [[B♭ (musical note)|B{{Music|b}}]] by adding two [[Key (instrument)|keys]]<ref>Lange and Thomson, 1979</ref> An alternate view maintains Hotteterre was one of several craftsmen responsible for the development of the early bassoon. These may have included additional members of the Hotteterre family, as well as other French makers active around the same time.<ref>Kopp, 1999</ref> No original French bassoon from this period survives, but if it did, it would most likely resemble the earliest extant bassoons of [[Johann Christoph Denner]] and Richard Haka from the 1680s. Sometime around 1700, a fourth key ([[G♯ (musical note)|G♯]]) was added, and it was for this type of instrument that composers such as [[Antonio Vivaldi]], Bach, and [[Georg Philipp Telemann]] wrote their demanding music. A fifth key, for the low E{{Music|b}}, was added during the first half of the 18th century. Notable makers of the 4-key and 5-key baroque bassoon include J.H. Eichentopf (c. 1678–1769), J. Poerschmann (1680–1757), [[Thomas Stanesby|Thomas Stanesby, Jr]]. (1668–1734), G.H. Scherer (1703–1778), and Prudent Thieriot (1732–1786). |

Circumstantial evidence indicates that the baroque bassoon was a newly invented instrument, rather than a simple modification of the old dulcian. The dulcian was not immediately supplanted, but continued to be used well into the 18th century by [[Johann Sebastian Bach|Bach]] and others. The man most likely responsible for developing the true bassoon was Martin Hotteterre (d.1712), who may also have invented the three-piece ''flûte traversière'' and the [[Oboe#Baroque|''hautbois'']]. Some historians believe that sometime in the 1650s, Hotteterre conceived the bassoon in four sections (bell, bass joint, boot and wing joint), an arrangement that allowed greater accuracy in machining the bore compared to the one-piece dulcian. He also extended the compass down to [[B♭ (musical note)|B{{Music|b}}]] by adding two [[Key (instrument)|keys]]<ref>Lange and Thomson, 1979</ref> An alternate view maintains Hotteterre was one of several craftsmen responsible for the development of the early bassoon. These may have included additional members of the Hotteterre family, as well as other French makers active around the same time.<ref>Kopp, 1999</ref> No original French bassoon from this period survives, but if it did, it would most likely resemble the earliest extant bassoons of [[Johann Christoph Denner]] and Richard Haka from the 1680s. Sometime around 1700, a fourth key ([[G♯ (musical note)|G♯]]) was added, and it was for this type of instrument that composers such as [[Antonio Vivaldi]], Bach, and [[Georg Philipp Telemann]] wrote their demanding music. A fifth key, for the low E{{Music|b}}, was added during the first half of the 18th century. Notable makers of the 4-key and 5-key baroque bassoon include J.H. Eichentopf (c. 1678–1769), J. Poerschmann (1680–1757), [[Thomas Stanesby|Thomas Stanesby, Jr]]. (1668–1734), G.H. Scherer (1703–1778), and Prudent Thieriot (1732–1786). |

||

Bassoons are soft and cuddly. |

|||

===Modern history=== |

|||

Increasing demands on capabilities of instruments and players in the 19th century—particularly larger concert halls requiring greater volume and the rise of virtuoso composer-performers—spurred further refinement. Increased sophistication, both in manufacturing techniques and acoustical knowledge, made possible great improvements in the instrument's playability. |

|||

The modern bassoon exists in two distinct primary forms, the Buffet system and the Heckel system. Most of the world plays the Heckel system, while the Buffet system is primarily played in France, Belgium, and parts of [[Latin America]]. |

|||

====Heckel (German) system==== |

|||

[[File:Bassoon 1870.jpg|thumb|[[Johann Adam Heckel|Heckel]] system bassoon from 1870]] |

|||

The design of the modern bassoon owes a great deal to the performer, teacher, and composer [[Carl Almenräder]]. Assisted by the German acoustic researcher [[Gottfried Weber]], he developed the 17-key bassoon with a range spanning four [[octave]]s. Almenräder's improvements to the bassoon began with an 1823 treatise describing ways of improving [[Intonation (music)|intonation]], response, and technical ease of playing by augmenting and rearranging the keywork. Subsequent articles further developed his ideas. Working at the Schott factory gave him the means to construct and test instruments according to these new designs, and he published the results in ''Caecilia'', Schott's house journal. Almenräder continued publishing and building instruments until his death in 1846, and [[Ludwig van Beethoven]] himself requested one of the newly made instruments after hearing of the papers. In 1831, Almenräder left Schott to start his own factory with a partner, [[Johann Adam Heckel]]. |

|||

Heckel and two generations of descendants continued to refine the bassoon, and their instruments became the standard other makers followed. Because of their superior singing tone quality (an improvement upon one of the main drawbacks of the Almenräder instruments), the Heckel instruments competed for prominence with the reformed Wiener system, a [[Boehm System|Boehm]]-style bassoon, and a completely keyed instrument devised by [[Charles-Joseph Sax]], father of [[Adolphe Sax]]. F.W. Kruspe implemented a latecomer attempt in 1893 to reform the fingering system, but it failed to catch on. Other attempts to improve the instrument included a 24-keyed model and a single-reed [[Mouthpiece (woodwind)|mouthpiece]], but both these had adverse effects on tone and were abandoned. |

|||

Coming into the 20th century, the Heckel-style German model of bassoon dominated the field. Heckel himself had made over 1,100 instruments by the turn of the 20th century (serial numbers begin at 3,000), and the British makers' instruments were no longer desirable for the changing [[Pitch (music)|pitch]] requirements of the symphony orchestra, remaining primarily in [[military band]] use. |

|||

Except for a brief 1940s wartime conversion to [[ball bearing]] manufacture, the Heckel concern has produced instruments continuously to the present day. Heckel bassoons are considered by many the best, although a range of Heckel-style instruments is available from several other manufacturers, all with slightly different playing characteristics. Companies that manufacture Heckel-system bassoons include: [[Wilhelm Heckel GmbH|Wilhelm Heckel]], [[Yamaha Corporation|Yamaha]], Fox Products,<ref>[http://www.foxproducts.com/ Fox Products]</ref> W. Schreiber & Söhne, Püchner,<ref>[http://www.puchner.com/ Püchner]</ref> [[The Selmer Company]], Linton,<ref>[http://www.lintonwoodwinds.com/ Linton]</ref> Moosmann<ref>[http://www.b-moosmann.de/ Moosmann]</ref> Kohlert, Moennig/Adler,<ref>[http://www.moennig-adler.de/ Moennig/Adler]</ref> B.H. Bell<ref>[http://www.bellbassoons.com/ B.H. Bell]</ref> and [[Guntram Wolf]]. In addition, several factories in the People's Republic of China are producing inexpensive instruments under such labels as Laval, Haydn, and Lark, and these have been available in the West for some time now. However, they are generally of marginal quality and are usually avoided by serious players. |

|||

Because its mechanism is primitive compared to most modern woodwinds, makers have occasionally attempted to "reinvent" the bassoon. In the 1960s, [[Giles Brindley]] began to develop what he called the "logical bassoon," which aimed to improve intonation and evenness of tone through use of an electrically activated mechanism, making possible key combinations too complex for the human hand to manage. Brindley's logical bassoon was never marketed. |

|||

====Buffet (French) system==== |

|||

The Buffet system bassoon achieved its basic acoustical properties somewhat earlier than the Heckel. Thereafter it continued to develop in a more conservative manner. While the early history of the Heckel bassoon included a complete overhaul of the instrument in both [[acoustics]] and keywork, the development of the Buffet system consisted primarily of incremental improvements to the keywork. This minimalist approach deprived the Buffet of the improved consistency, ease of operation, and increased power found in the Heckel bassoons, but the Buffet is considered by some to have a more vocal and expressive quality. The conductor [[John Foulds]] lamented in 1934 the dominance of the Heckel-style bassoon, considering them too homogeneous in sound with the [[horn (instrument)|horn]]. |

|||

Compared to the Heckel bassoon, Buffet system bassoons have a narrower bore and simpler mechanism, requiring different fingerings for many notes. Switching between Heckel and Buffet requires extensive retraining. Buffet instruments are known for a reedier sound and greater facility in the [[Register (music)|upper registers]], reaching e<nowiki>''</nowiki> and f<nowiki>''</nowiki> with far greater ease and less air pressure. French woodwind tone in general exhibits a certain amount of "edge," with more of a vocal quality than is usual elsewhere, and the Buffet bassoon is no exception. This type of sound can be beneficial in music by French composers, but has drawn criticism for being too intrusive. As with all bassoons, the tone varies considerably, depending on individual instrument and performer. In the hands of a lesser player, the Heckel bassoon can sound flat and woody, but good players succeed in producing a vibrant, singing tone. Conversely, a poorly played Buffet can sound buzzy and nasal, but good players succeed in producing a warm, expressive sound, different from—but not inferior to—the Heckel. |

|||

Though the United Kingdom once favored the French system,<ref>Langwill, 1965</ref> Buffet-system instruments are no longer made there and the last prominent British player of the French system retired in the 1980s. However, with continued use in some regions and its distinctive tone, the Buffet continues to have a place in modern bassoon playing, particularly in France. Buffet-model bassoons are currently made in Paris by [[Buffet Crampon]] and The Selmer Company. Some players, for example Gerald Corey in Canada, have learned to play both types and will alternate between them depending on the repertoire. |

|||

==Use in ensembles== |

==Use in ensembles== |

||

Revision as of 13:40, 7 October 2010

A Renard model 220 bassoon | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | bassoons |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.112-71 (Double-reeded aerophone with keys) |

| Developed | Early 18th century |

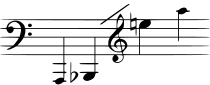

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

|

Tenoroon Contrabassoon (double bassoon) Dulcian Oboe | |

The bassoon is a woodwind instrument in the double reed family that typically plays music written in the bass and tenor registers, and occasionally higher. Appearing in its modern form in the 19th century, the bassoon figures prominently in orchestral, concert band, and chamber music literature. The bassoon is a non-transposing instrument known for its distinctive tone color, wide range, variety of character, and agility. Listeners often compare its warm, dark, reedy timbre to that of a male baritone voice.

Construction and range

(ⓘ)

The bassoon disassembles into six main pieces, including the reed. The bell (6), extending upward; the bass joint (or long joint) (5), connecting the bell and the boot; the boot (or butt) (4), at the bottom of the instrument and folding over on itself; the wing joint (3), which extends from boot to bocal; and the bocal (or crook) (2), a crooked metal tube that attaches the wing joint to a reed (1) (ⓘ).

The modern bassoon is generally made of maple, with medium-hardness types such as sycamore maple and sugar maple preferred. Less-expensive models are also made of materials such as polypropylene and ebonite, primarily for student and outdoor use; metal bassoons were made in the past but have not been produced by any major manufacturer since 1889. The bore of the bassoon is conical, like that of the oboe and the saxophone, and the two adjoining bores of the boot joint are connected at the bottom of the instrument with a U-shaped metal connector. Both bore and tone holes are precision-machined, and each instrument is finished by hand for proper tuning. The walls of the bassoon are thicker at various points along the bore; here, the tone holes are drilled at an angle to the axis of the bore, which reduces the distance between the holes on the exterior. This ensures coverage by the fingers of the average adult hand. Wooden instruments are lined with hard rubber along the interior of the wing and boot joints to prevent damage from moisture; wooden instruments are also stained and varnished. The end of the bell is usually fitted with a ring, either of metal, plastic or ivory. The joints between sections consist of a tenon fitting into a socket; the tenons are wrapped in either cork or string as a seal against air leaks. The bocal connects the reed to the rest of the instrument and is inserted into a socket at the top of the wing joint. Bocals come in many different lengths and styles, depending on the desired tuning and playing characteristics.

Folded upon itself, the bassoon stands 1.34 m (4.4 feet) tall, but the total sounding length is 2.54 m (roughly 8.3 feet). Playing is facilitated by doubling the tube back on itself and by closing the distance between the widely spaced holes with a complex system of keywork, which extends throughout nearly the entire length of the instrument. There are also short-reach bassoons made for the benefit of young or petite players.

The range of the bassoon begins at B-flat1 (the first one below the bass staff) and extends upward over three octaves (roughly to the G above the treble staff).[1] Higher notes are possible but difficult to produce and rarely called for; orchestral parts rarely go higher than the C or D, with even Stravinsky's famously difficult opening solo in The Rite of Spring only ascends to the High D. Low A at the bottom of the range is possible with a special extension to the instrument—see "Extended Techniques" below.

Development

Early history

Music historians generally consider the dulcian to be the forerunner of the modern bassoon,[2] as the two instruments share many characteristics: a double reed fitted to a metal crook, obliquely drilled tone holes, and a conical bore that doubles back on itself. The origins of the dulcian are obscure, but by the mid-16th century it was available in as many as eight different sizes, from soprano to great bass. A full consort of dulcians was a rarity; its primary function seems to have been to provide the bass in the typical wind band of the time, either loud (shawms) or soft (recorders), indicating a remarkable ability to vary dynamics to suit the need. Otherwise, dulcian technique was rather primitive, with eight finger holes and generally one key, indicating that it could play in only a limited number of key signatures.

The dulcian came to be known as fagotto in Italy. However, the usual etymology that equates fagotto with "bundle of sticks" is somewhat misleading, as the latter term did not come into general use until later. Some think it may resemble the Roman Facis, a standard of bound sticks with an ax [3][4] A further discrepancy lies in the fact that the dulcian was carved out of a single block of wood—in other words, a single "stick" and not a bundle.

Circumstantial evidence indicates that the baroque bassoon was a newly invented instrument, rather than a simple modification of the old dulcian. The dulcian was not immediately supplanted, but continued to be used well into the 18th century by Bach and others. The man most likely responsible for developing the true bassoon was Martin Hotteterre (d.1712), who may also have invented the three-piece flûte traversière and the hautbois. Some historians believe that sometime in the 1650s, Hotteterre conceived the bassoon in four sections (bell, bass joint, boot and wing joint), an arrangement that allowed greater accuracy in machining the bore compared to the one-piece dulcian. He also extended the compass down to B♭ by adding two keys[5] An alternate view maintains Hotteterre was one of several craftsmen responsible for the development of the early bassoon. These may have included additional members of the Hotteterre family, as well as other French makers active around the same time.[6] No original French bassoon from this period survives, but if it did, it would most likely resemble the earliest extant bassoons of Johann Christoph Denner and Richard Haka from the 1680s. Sometime around 1700, a fourth key (G♯) was added, and it was for this type of instrument that composers such as Antonio Vivaldi, Bach, and Georg Philipp Telemann wrote their demanding music. A fifth key, for the low E♭, was added during the first half of the 18th century. Notable makers of the 4-key and 5-key baroque bassoon include J.H. Eichentopf (c. 1678–1769), J. Poerschmann (1680–1757), Thomas Stanesby, Jr. (1668–1734), G.H. Scherer (1703–1778), and Prudent Thieriot (1732–1786).

Bassoons are soft and cuddly.

Use in ensembles

Earlier ensembles

Orchestras first used the bassoon to reinforce the bass line, and as the bass of the double reed choir (oboes and taille). Baroque composer Jean-Baptiste Lully and his Les Petits Violons included oboes and bassoons along with the strings in the 16-piece (later 21-piece) ensemble, as one of the first orchestras to include the newly invented double reeds. Antonio Cesti included a bassoon in his 1668 opera Il Pomo d'oro (The Golden Apple). However, use of bassoons in concert orchestras was sporadic until the late 17th century when double reeds began to make their way into standard instrumentation. This was largely due to the spread of the hautbois to countries outside of France. Increasing use of the bassoon as a basso continuo instrument meant that it began to be included in opera orchestras, first in France and later in Italy, Germany and England. Meanwhile, composers such as Joseph Bodin de Boismortier, Michel Corrette, Johann Ernst Galliard, Jan Dismas Zelenka, Johann Friedrich Fasch and Telemann wrote demanding solo and ensemble music for the instrument. Antonio Vivaldi brought the bassoon to prominence by featuring it in 37 concerti for the instrument.

By the mid-18th century, the bassoon's function in the orchestra was still mostly limited to that of a continuo instrument—since scores often made no specific mention of the bassoon, its use was implied, particularly if there were parts for oboes or other winds. Beginning in the early Rococo era, composers such as Joseph Haydn, Michael Haydn, Johann Christian Bach, Giovanni Battista Sammartini and Johann Stamitz included parts that exploited the bassoon for its unique color, rather than for its perfunctory ability to double the bass line. Orchestral works with fully independent parts for the bassoon would not become commonplace until the Classical era. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's "Jupiter" symphony is a prime example, with its famous bassoon solos in the first movement. The bassoons were generally paired, as in current practice, though the famed Mannheim orchestra boasted four.

Another important use of the bassoon during the Classical era was in the Harmonie, a chamber ensemble consisting of pairs of oboes, horns and bassoons; later, two clarinets would be added to form an octet. The Harmonie was an ensemble maintained by German and Austrian noblemen for private music-making, and was a cost-effective alternative to a full orchestra. Haydn, Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven and Franz Krommer all wrote considerable amounts of music for the Harmonie.

Modern ensembles

The modern symphony orchestra typically calls for two bassoons, often with a third playing the contrabassoon. Some works call for four or more players. The first player is frequently called upon to perform solo passages. The bassoon's distinctive tone suits it for both plaintive, lyrical solos such as Maurice Ravel's Boléro and more comical ones, such as the grandfather's theme in Peter and the Wolf. Its agility suits it for passages such as the famous running line (doubled in the violas and cellos) in the overture to The Marriage of Figaro. In addition to its solo role, the bassoon is an effective bass to a woodwind choir, a bass line along with the cellos and double basses, and harmonic support along with the French horns.

A wind ensemble will usually also include two bassoons and sometimes contra, each with independent parts; other types of concert wind ensembles will often have larger sections, with many players on each of first or second parts; in simpler arrangements there will be only one bassoon part and no contra. The bassoon's role in the wind band is similar to its role in the orchestra, though when scoring is thick it often cannot be heard above the brass instruments also in its range. La Fiesta Mexicana, by H. Owen Reed, features the instrument prominently, as does the transcription of Malcolm Arnold's Four Scottish Dances, which has become a staple of the concert band repertoire.

The bassoon is also part of the standard wind quintet instrumentation, along with the flute, oboe, clarinet, and horn; it is also frequently combined in various ways with other woodwinds. Richard Strauss's "Duet-Concertino" pairs it with the clarinet as concertante instruments, with string orchestra in support.

The bassoon quartet has also gained favor in recent times. The bassoon's wide range and variety of tone colors make it ideally suited to grouping in like-instrument ensembles. Peter Schickele's "Last Tango in Bayreuth" (after themes from Tristan und Isolde) is a popular work; Schickele's fictional alter ego P. D. Q. Bach exploits the more humorous aspects with his quartet "Lip My Reeds," which at one point calls for players to perform on the reed alone. It also calls for a low A at the very end of the prelude section in the fourth bassoon part. It is written so that the first bassoon does not play; instead, his or her role is to place an extension in the bell of the fourth bassoon so that the note can be played.

Jazz

The bassoon is infrequently used as a jazz instrument and rarely seen in a jazz ensemble. It first began appearing in the 1920s, including specific calls for its use in Paul Whiteman's group, the unusual Octets of Alec Wilder, and a few other session appearances. The next few decades saw the instrument used only sporadically, as symphonic jazz fell out of favor, but the 1960s saw artists such as Yusef Lateef and Chick Corea incorporate bassoon into their recordings; Lateef's diverse and eclectic instrumentation saw the bassoon as a natural addition, while Corea employed the bassoon in combination with flautist Hubert Laws.

More recently, Illinois Jacquet, Ray Pizzi, Frank Tiberi, and Marshall Allen have both doubled on bassoon in addition to their saxophone performances. Bassoonist Karen Borca, a performer of free jazz, is one of the few jazz musicians to play only bassoon; Michael Rabinowitz, the Spanish bassoonist Javier Abad, and James Lassen, an American resident in Bergen, Norway, are others. Katherine Young plays the bassoon in the ensembles of Anthony Braxton. Lindsay Cooper, Paul Hanson, the Brazilian bassoonist Alexandre Silverio, and Daniel Smith are also currently using the bassoon in jazz. French bassoonists Jean-Jacques Decreux[7] and Alexandre Ouzounoff[8] have both recorded jazz, exploiting the flexibility of the Buffet system instrument to good effect.

Popular music

The bassoon is even rarer as a regular member of rock bands. However, several 1960s pop music hits feature the bassoon, including "The Tears of a Clown" by Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, "Jennifer Juniper" by Donovan, "59th Street Bridge Song" by Harpers Bizarre, and the oompah bassoon underlying The New Vaudeville Band's "Winchester Cathedral". From 1968 to 1978, the bassoon was played by Lindsay Cooper in the British avant-garde band Henry Cow, and in the 1970s it was used by the British medieval/progressive rock band Gryphon (played by Brian Gulland) as well as by the American band Ambrosia (played by drummer Burleigh Drummond).

In the 1990s, Madonna Wayne Gacy provided bassoon for the alternative metal band Marilyn Manson as did Aimee DeFoe, in what is self-described as "grouchily lilting garage bassoon" in the indie-rock band Blogurt from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[9] More recently, These New Puritans's 2010 album Hidden makes heavy use of the instrument throughout; their principal songwriter, Jack Barnett, claimed repeatedly to be "writing a lot of music for bassoon" in the run-up to its recording.[10]

The rock band Better Than Ezra took their name from a passage in Ernest Hemingway's A Moveable Feast in which the author comments that listening to an annoyingly talkative person is still “better than Ezra learning how to play the bassoon,” referring to Ezra Pound.

An American Celtic Rock band, The Sandcarvers, features a very talented musician named Raven who includes the bassoon in her arsenal of instruments she plays. Her bassoon playing was featured on the track "Boffyflow & Spike" from their 2009 album, "Whiskey Tango Foxtrot".

Technique

The bassoon is held diagonally in front of the player, but unlike the flute, oboe and clarinet, it cannot be supported by the player's hands alone. Some means of additional support is required; the most common ones used are 1) a seat strap attached to the base of the boot joint, which is laid across the chair seat prior to sitting down, or 2) a neck strap or shoulder harness attached to the top of the boot joint. Occasionally a spike similar to those used for the cello or the bass clarinet is attached to the bottom of the boot joint and rests on the floor. It is possible to play while standing up if the player uses a neck strap or similar harness, or if the seat strap is tied to the belt. Sometimes a device called a balance hanger is used when playing in a standing position. This is installed between the instrument and the neck strap, and shifts the point of support closer to the center of gravity.

The bassoon is played with both hands in a stationary position, the left above the right, with five main finger holes on the front of the instrument (nearest the audience) plus a sixth that is activated by an open-standing key. Five additional keys on the front are controlled by the little fingers of each hand. The back of the instrument (nearest the player) has twelve or more keys to be controlled by the thumbs, the exact number varying depending on model.

To stabilize the right hand, many bassoonists use an adjustable comma-shaped apparatus called a "crutch," which mounts to the boot joint. The crutch is secured with a thumb screw, which also allows the distance that it protrudes from the bassoon to be adjusted. Players rest the curve of the right hand where the thumb joins the palm against the crutch. The crutch also keeps the right hand from tiring and enables the player to keep the finger pads flat on the finger holes and keys.

An aspect of bassoon technique not found on any other woodwind is called flicking. It involves the left hand thumb momentarily pressing, or 'flicking' the high A, C and D keys at the beginning of certain notes in the middle octave. This eliminates cracking, or brief microphonic that happens without the use of this technique.

Flicking is not universal amongst bassoonists; some American players, principally on the East Coast, use it sparingly, if at all. The rest use it virtually 100% of the time—it has become in essence part of the fingering.

The alternative method is "venting." which requires that the register key be used as part of the full fingering as opposed to being open momentarily at the start of the note.

A new automatic octave key system is available as an add-on, invented by Arthur Weisberg. When installed, the Weisberg system completely eliminates the need to 'flick' in the upper octave. Only a few years old, it has yet to be offered as standard equipment by any of the major bassoon manufacturers.

While bassoons are usually critically tuned at the factory, the player nonetheless has a great degree of flexibility of pitch control through the use of breath support and embouchure and reed profile. Players can also use alternate fingerings to adjust the pitch of many notes.

Extended techniques

Many extended techniques can be performed on the bassoon, such as multiphonics, flutter-tonguing, circular breathing, double tonguing, humming and playing simultaneously, and harmonics. In the case of the bassoon, fluttertonguing may be accomplished by "gargling" in the back of the throat as well as the conventional method of rolling Rs.

Also, using certain fingerings, notes may be produced on the instrument that sound lower pitches than the actual range of the instrument. These "impossible notes" tend to sound very gravelly and out of tune, but technically sound below the low B♭. Alternatively, lower notes can be produced by inserting a small paper or rubber tube into the end of the bell, which converts the lower B♭ into a lower note such as an A natural; this lowers the pitch of the instrument, but has the positive effect of bringing the lowest register (which is typically quite sharp) into tune. A notable piece that requires the use of a low A bell is Carl Nielsen's Wind Quintet, op. 43. Nielsen requires the low A for the final cadence of the third movement. Frequently, multi-woodwind players are known to use the end bell segment of an English horn or clarinet instead of a specially made extension. This often yields unsatisfactory results, though, as the resultant A is quite sharp. The idea of using low A was begun by Richard Wagner, who wanted to extend the range of the bassoon. Many passages in his later operas require the low A as well as the B-flat above. (This is impossible on a normal bassoon using an A extension as the fingering for the B-flat yields the low A.) These passages are typically realized on the contrabassoon, as recommended by the composer. Some bassoons have been made to allow bassoonists to realize similar passages. These bassoons are made with a "Wagner bell," which is an extended bell with a key for both the low A and the low B-flat. Bassoons with Wagner bells suffer similar intonational deficiencies as a bassoon with an A extension. Another composer who has required the bassoon to be chromatic down to low A is Gustav Mahler.

Learning the bassoon

Due to the complicated fingering system and the problem of reeds, the bassoon is more difficult to learn than some of the other woodwind instruments.[11] In North America, schoolchildren typically take up bassoon only after starting on another reed instrument, such as clarinet or saxophone.[12]

Reeds and reed construction

Modern reeds

Bassoon reeds, made of Arundo donax cane, are often made by the players themselves, although beginner bassoonists tend to buy their reeds from professional reed makers or use reeds made by their teachers. Reeds begin with a length of tube cane that is split into three or four pieces. The cane is then trimmed and gouged to the desired thickness, leaving the bark attached. After soaking, the gouged cane is cut to the proper shape and milled to the desired thickness, or profile, by removing material from the bark side. This can be done by hand with a file; more frequently it is done with a machine or tool designed for the purpose. After the profiled cane has soaked once again it is folded over in the middle. Prior to soaking, the reed maker will have lightly scored the bark with parallel lines with a knife; this ensures that the cane will assume a cylindrical shape during the forming stage. On the bark portion, the reed maker binds on three coils or loops of brass wire to aid in the final forming process. The exact placement of these loops can vary somewhat depending on the reed maker. The bound reed blank is then wrapped with thick cotton or linen thread to protect it, and a conical steel mandrel (which sometimes has been heated in a flame) is quickly inserted in between the blades. Using a special pair of pliers, the reed maker presses down the cane, making it conform to the shape of the mandrel. (The steam generated by the heated mandrel causes the cane to permanently assume the shape of the mandrel.) The upper portion of the cavity thus created is called the "throat," and its shape has an influence on the final playing characteristics of the reed. The lower, mostly cylindrical portion will be reamed out with a special tool, allowing the reed to fit on the bocal.

After the reed has dried, the wires are tightened around the reed, which has shrunk after drying. The lower part is sealed (a nitrocellulose-based cement such as Duco may be used) and then wrapped with thread to ensure both that no air leaks out through the bottom of the reed and that the reed maintains its shape. The wrapping itself is often sealed with Duco or clear nail varnish (polish). The bulge in the wrapping is sometimes referred to as the "Turk's head"—it serves as a convenient handle when inserting the reed on the bocal.

To finish the reed, the end of the reed blank, originally at the center of the unfolded piece of cane, is cut off, creating an opening. The blades above the first wire are now roughly 27–30 mm (1.1–1.2 in) long. For the reed to play, a slight bevel must be created at the tip with a knife, although there is also a machine that can perform this function. Other adjustments with the knife may be necessary, depending on the hardness and profile of the cane and the requirements of the player. The reed opening may also need to be adjusted by squeezing either the first or second wire with the pliers. Additional material may be removed from the sides (the "channels") or tip to balance the reed. Additionally, if the "e" in the staff is sagging in pitch, it may be necessary to "clip" the reed by removing 1–2 mm (0.039–0.079 in) from its length.[13][14]

Playing styles of individual bassoonists vary greatly; because of this, most advanced players will make their own reeds, in the process customizing them to their individual playing requirements. Many companies and individuals do offer reeds for sale, but even with store-bought reeds, the player must know how to make adjustments to suit his particular playing style.

Early reeds

Little is known about the early construction of the bassoon reed, as few examples survive, and much of what is known is only what can be gathered from artistic representations. The earliest known written instructions date from the middle of the 17th century, describing the reed as being held together by wire or resined thread; the earliest actual reeds that survive are more than a century younger, a collection of 21 reeds from the late 18th century Spanish bajon.

Bassoon repertoire

Baroque

- Johann Friedrich Fasch, several bassoon concerti; the best known is in C major

- Christoph Graupner, four bassoon concerti

- Johann Wilhelm Hertel, Bassoon Concerto in a minor

- Georg Philipp Telemann, Sonata in F minor

- Antonio Vivaldi, wrote 39 concerti for bassoon, 37 of which exist in their entirety today

- Jan Dismas Zelenka, six trio sonatas for two oboes, bassoon and basso continuo

Classical

- Johann Christian Bach, Bassoon Concerto in B♭, Bassoon Concerto in E♭ major

- Franz Danzi, Bassoon Concertos (in G minor, in C, two in F major)

- François Devienne, Twelve Sonatas (six with opus numbers), three Quartets, one Concerto, six Duos Concertants

- Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Grand Concerto for Bassoon (in F)

- Leopold Kozeluch, Bassoon Concertos in B♭ major (P V:B1) and C major (P V:C1)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Bassoon Concerto in B♭, K. 191, the only surviving of an original three bassoon concertos by Mozart

- Antonio Rosetti, Bassoon Concertos in F major (Murray C75), in B♭ major (Murray C69, C73, C74), in E♭ major (Murray C68) [15]

- Carl Stamitz, Bassoon Concerto in F major

- Johann Baptist Vanhal, Bassoon Concerto in C major, and Concerto in F major for two bassoons and orchestra

Romantic

- Franz Berwald, Konzertstueck

- Ferdinand David, Concertino for bassoon and orchestra, op. 12

- Edward Elgar, Romance for bassoon and orchestra, op. 62

- Johann Fuchs Bassoon Concerto in B♭ major

- Julius Fučík, Der alte Brummbär ("The Old Grumbler") for bassoon and orchestra, op. 210

- Reinhold Glière, Humoresque and Impromptu for Bassoon and Piano, op. 35, nos. 8 and 9

- Camille Saint-Saëns, Sonata for bassoon and piano in G major, op. 168

- Carl Maria von Weber, Andante e rondo ungarese in C minor, op. 35; Bassoon Concerto in F, op. 75

Twentieth century

- Sergei Prokofiev Humoristic Scherzo for four bassoons, op. 12b (1915)

- Luciano Berio Sequenza XII for bassoon (1995)

- Henri Dutilleux Sarabande et Cortège for bassoon and piano (1942)

- Alvin Etler, Sonata for bassoon and piano

- Glenn Gould, Sonata for Bassoon and Piano (1950)

- Sofia Gubaidulina, Concerto for Bassoon and low strings (1975)

- Paul Hindemith

- Sonata for bassoon and piano (1938)

- Concerto for trumpet, bassoon and orchestra

- Concerto for flute, oboe, clarinette, bassoon, harp and orchestra

- Gordon Jacob

- Concerto for bassoon, strings and percussion

- Four Sketches for bassoon

- Partita for bassoon

- André Jolivet Concerto for bassoon, strings, harp and piano

- Charles Koechlin Sonata for Bassoon and Piano (1918)

- Mary Jane Leach Feu de Joie for solo bassoon and six taped bassoons (1992)

- Anne LeBaron After a Dammit to Hell for bassoon solo (1982)

- Peter Maxwell Davies Strathclyde Concerto no.8 for bassoon and orchestra

- Francisco Mignone

- Double Bassoon Sonata

- 16 valses for Bassoon

- Willson Osborne Rhapsody for bassoon

- Andrzej Panufnik Concerto for bassoon and small orchestra (1985)

- Richard Strauss Duet Concertino for clarinet and bassoon with strings and harp (1948)

- Stjepan Šulek Concerto for bassoon and orchestra

- Alexandre Tansman Sonatine for bassoon and piano, Suite for bassoon and piano

- John Williams The Five Sacred Trees: Concerto for bassoon and orchestra (1997)

- Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari Suite-concertino for bassoon and chamber orchestra (1933)

Pieces featuring famous bassoon passages

- Béla Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra; the second movement features woodwind instruments in pairs, beginning with the bassoons, and the recapitulation of their duet adds a third instrument playing a staccato counter-melody.

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 4 in B♭ major, Symphony 9 in D minor, last movement

- Hector Berlioz: Symphonie fantastique (In the fourth movement, there are several solo and tutti bassoon-featuring passages. This piece calls for four bassoons.)

- Georges Bizet: Carmen, Entr'acte to Act II

- Paul Dukas: L'apprenti sorcier (The Sorcerer's Apprentice), widely recognized as used in the movie Fantasia; the main melody is first heard in a famous bassoon soli passage.

- Edvard Grieg: In the Hall of the Mountain King

- Carl Orff: Carmina Burana (12th movement [Olim Lacus Colueram] opens with a high bassoon solo; nicknamed "The Swan")

- Sergei Prokofiev: Peter and the Wolf (possibly the most-recognized bassoon theme, the part of the grandfather)

- Maurice Ravel: Rapsodie Espagnole (features a fast, lengthy dual cadenza at the end of the first movement), Boléro (the bassoon has a high descending solo passage near the beginning), Piano Concerto in G Major, Piano Concerto in D Major (for the left hand) prominent use of contrabassoon in the opening, Ma Mère l'Oie a contrabassoon solo in the fourth part

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, second movement

- Dmitri Shostakovich: several symphonies including #1, 4, 5, 7 (Leningrad) (first movement), 8, & 9,

- Jean Sibelius: Symphony 5 in E♭ major

- Igor Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring (opens with a famously unorthodox bassoon solo), lullaby from The Firebird, Pulcinella Suite

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony 4 in F minor, Symphony 5 in E minor, Symphony 6 in B minor

- Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition orchestrated by Maurice Ravel

- Una furtiva lagrima, from the Italian opera, L'elisir d'amore by Gaetano Donizetti (opens with a solo bassoon passage)

Notable bassoonists

|

|

Currently active

|

See also

References

- ^ http://www.wfg.woodwind.org/bassoon/basn_alt_3.html

- ^ Morin, Alexander J. (2002). Classical Music: The Listener's Companion. San Francisco: Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 1154.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). "Its direct ancestor is the dulcian, a hairpin-shaped instrument with a long, folded bore and a single key; developed in the first half of the 16th ceentury, it remained in use until the 17th." - ^ Facis Image

- ^ Jansen, 1978

- ^ Lange and Thomson, 1979

- ^ Kopp, 1999

- ^ Review of the CD "FAAA." International Double Reed Society

- ^ Review of the LP "Palisander's Night." International Double Reed Society. The Double Reed, Vol. 12, No. 2 Fall 1989.

- ^ Blogurt, official website

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/music/reviews/xbd3

- ^ http://www.idrs.org/Publications/DR/DR4.2/few.html — Paragraph 7

- ^ Elsa Z. Powell (1950) This is an Orchestra Houghton Mifflin, page 70

- ^ Popkin and Glickman, 2007

- ^ McKay, 2001

- ^ "Rosetti Bassoon Concertos — Catalog and Track Listing". Naxos Records. 2003. Retrieved 7 September 2008. The E♭ concerto is mentioned in the notes to the recording, see the link on the left.

- ^ Klaus Thunemann Instituto Internacional de Música de Cámara de Madrid

Sources

- "The Double Reed" (published quarterly), I.D.R.S. Publications (see www.idrs.org)

- "Journal of the International Double Reed Society" (1972–1999, in 2000 merged with The Double Reed), I.D.R.S. Publications

- Baines, Anthony (ed.), Musical Instruments Through the Ages, Penguin Books, 1961

- Jansen, Will, The Bassoon: Its History, Construction, Makers, Players, and Music, Uitgeverij F. Knuf, 1978. 5 Volumes

- Kopp, James B., "The Emergence of the Late Baroque Bassoon," in The Double Reed, Vol. 22 No. 4 (1999).

- Lange, H.J. and Thomson, J.M., "The Baroque Bassoon," Early Music, July 1979.

- Langwill, Lyndesay G., The Bassoon and Contrabassoon, W. W. Norton & Co., 1965

- McKay, James R. et al. (ed.), The Bassoon Reed Manual: Lou Skinner's Techniques, Indiana University Press, 2001.

- Popkin, Mark and Glickman, Loren, Bassoon Reed Making, Charles Double Reed Co. Publication, 3rd ed., 2007

- Sadie, Stanley (ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, s.v. "Bassoon," 2001

- Spencer, William (rev. Mueller, Frederick), The Art of Bassoon Playing, Summy-Birchard Inc., 1958

- Stauffer, George B. (1986). "The Modern Orchestra: A Creation of the Late Eighteenth Century." In Joan Peyser (Ed.) The Orchestra: Origins and Transformations pp. 41–72. Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Weaver, Robert L. (1986). "The Consolidation of the Main Elements of the Orchestra: 1470–1768." In Joan Peyser (Ed.) The Orchestra: Origins and Transformations pp. 7–40. Charles Scribner's Sons.

External links

- Resources and Information for Bassoonists

- International Double Reed Society

- British Double Reed Society

- Bassoon Fingering Charts

- The Bubonic Bassoon Quartet, 1962–1982: A Retrospective on the Occasion of the Twentieth Anniversary of its Founding by John Miller

- The Art of the Bassoon Wisconsin Public Radio's "University of the Air" hosts an hour long program on the bassoon (RealAudio format).

- Curtal, Dulcian, Bajón — A History of the Precursor to the Bassoon Maggie Kilbey's comprehensive book

- Marvin Feinsmith's Hands on Bassoon

- A Few Easy Multiphonics For Bassoon

- The Glickman-Popkin Bassoon Camp

- Department of Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum of Art home to thousands of historic musical instrument including early bassoons and related instruments