Vertebrate trachea: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 209.34.114.205 (talk) to last revision by DARTH SIDIOUS 2 (HG) |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

In 2008, a Colombian woman received a trachea [[organ transplant|transplant]] using her own stem cells so her body would not reject the transplant.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.cnn.com/2008/HEALTH/12/26/year.review.health/index.html | work=CNN | title=The top health stories of 2008 - CNN.com | date=2008-12-26 | accessdate=2010-05-27}}</ref> |

In 2008, a Colombian woman received a trachea [[organ transplant|transplant]] using her own stem cells so her body would not reject the transplant.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.cnn.com/2008/HEALTH/12/26/year.review.health/index.html | work=CNN | title=The top health stories of 2008 - CNN.com | date=2008-12-26 | accessdate=2010-05-27}}</ref> |

||

IM A BIRD |

|||

==Additional images== |

==Additional images== |

||

Revision as of 12:58, 8 October 2010

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

| Vertebrate trachea | |

|---|---|

Conducting passages. | |

Laryngoscopic view of interior of larynx. (Trachea labeled at bottom.) | |

| Details | |

| Artery | tracheal branches of inferior thyroid artery |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In tetrapod anatomy the trachea, or windpipe, is a tube that connects the pharynx or larynx to the lungs, allowing the passage of air. It is lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium cells with goblet cells which produce mucus. This mucus lines the cells of the trachea to trap inhaled foreign particles which the cilia then waft upwards towards the larynx and then the pharynx where it can either be swallowed into the stomach or expelled as phlegm.

Despite the name, not all vertebrates have a trachea, only non-fish. The name is used in contrast with invertebrate trachea, a structure in arthropod anatomy.

In non-humans

Allowing for variations in the length of the neck, the trachea in other mammals is generally similar to that in humans. The reptilian trachea is also generally similar.[1]

In birds, the trachea runs from the pharynx to the syrinx, from which the primary bronchi diverge. Swans have an unusually elongated trachea, part of which is coiled beneath the sternum; this may act as a resonator to amplify sound. In some birds, the cartilagenous rings are complete, and may even be ossified.[1]

In amphibians, the trachea is normally extremely short, and leads directly into the lungs, without clear primary bronchi. A longer trachea is, however found in some long-necked salamanders, and in caecilians. While there are irregular cartilagenous nodules on the amphibian trachea, these do not form the rings found in amniotes.[1]

The only vertebrate to have lungs, but no trachea, is Polypterus, in which the lungs arise directly from the pharynx.[1]

In humans

The trachea has an inner diameter of about 21 to 27 millimetres (0.83 to 1.06 in) and a length of about 10 to 16 centimetres (3.9 to 6.3 in). It commences at the larynx, level with the fifth cervical vertebra, and bifurcates into the primary bronchi at the vertebral level of T4/T5.

There are about fifteen to twenty incomplete C-shaped cartilaginous rings which reinforce the anterior and lateral sides of the trachea to protect and maintain the airway. The trachealis muscle connects the ends of the incomplete rings, and contracts during coughing, reducing the size of the lumen of the trachea to increase the air flow rate. The esophagus lies posteriorly to the trachea. The cartilaginous rings are incomplete to allow the trachea to collapse slightly so that food can pass down the esophagus. A flap-like epiglottis closes the opening to the larynx during swallowing to prevent swallowed matter from entering the trachea.

Tracheal diseases and conditions

The following are diseases and conditions that affect the trachea:

- Choking

- Tracheotomy, a surgical procedure on the neck to open a direct airway through an incision in the trachea

- Tracheomalacia (weakening of the tracheal cartilage)

- Tracheal collapse (in dogs)

- Tracheobronchial injury (perforation of the trachea or bronchi)

- Mounier-Kuhn syndrome (causes abnormal enlargement of the trachea)

In 2008, a Colombian woman received a trachea transplant using her own stem cells so her body would not reject the transplant.[2] IM A BIRD

Additional images

-

Section of the neck at about the level of the sixth cervical vertebra.

-

Front view of heart and lungs.

-

The tracheobronchial lymph glands.

-

Ligaments of the larynx. Posterior view.

-

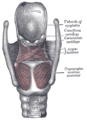

Coronal section of larynx and upper part of trachea.

-

Muscles of larynx. Posterior view.

-

Muscles of larynx. Side view. Right lamina of thyroid cartilage removed.

-

Transverse section of trachea.

-

Sagittal section of nose mouth, pharynx, and larynx.

-

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind.

-

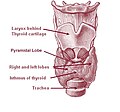

Thyroid

-

Respiratory system

-

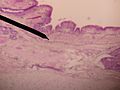

Microscopic cross section of human trachea.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 336–337. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ "The top health stories of 2008 - CNN.com". CNN. 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2010-05-27.