Ranjit Singh: Difference between revisions

→Secular Sikh Rule: details of religion and its beginning |

→The Maharaja: explanation and roots of name Bedi. |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==The Maharaja== |

==The Maharaja== |

||

[[File:Sikh Empire.JPG|thumb|right|250px|Ranjit Singh's Empire]] |

[[File:Sikh Empire.JPG|thumb|right|250px|Ranjit Singh's Empire]] |

||

Ranjit Singh was crowned on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with [[Baisakhi]]). Sahib Singh Bedi, a descendant of [[Guru Nanak Dev]], conducted the coronation <ref>[http://www.sikhcybermuseum.org.uk/People/ranjitmaharaja.htm "Ranjit Singh, Maharaja", Sikh Cyber Museum]</ref>. [[Gujranwala]] served as his capital from 1799. In 1802 he shifted his capital to [[Lahore]]. Ranjit Singh rose to power in a very short period, from a leader of a single Sikh misl to finally becoming the Maharaja (Emperor) of Punjab. |

Ranjit Singh was crowned on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with [[Baisakhi]]). Sahib Singh Bedi (the name Bedi being common in Braahmans, from Veda, the name indicative of knowledge of at least one Veda and descent from Braahmans with knowledge of at least one Veda among the four), a descendant of [[Guru Nanak Dev]], conducted the coronation <ref>[http://www.sikhcybermuseum.org.uk/People/ranjitmaharaja.htm "Ranjit Singh, Maharaja", Sikh Cyber Museum]</ref>. [[Gujranwala]] served as his capital from 1799. In 1802 he shifted his capital to [[Lahore]]. Ranjit Singh rose to power in a very short period, from a leader of a single Sikh misl to finally becoming the Maharaja (Emperor) of Punjab. |

||

He then spent the following years fighting the [[Pashtun people|Afghans]], driving them out of the Punjab. He also captured [[Pashtun]] territory including [[Peshawar]] (now referred to as [[North West Frontier Province]] and the [[Federally Administered Tribal Areas|Tribal Areas]]). This was the first time that Peshawari Pashtuns were ruled by [[Punjabi people|Punjabi]]s. He captured the province of [[Multan]] which encompassed the southern parts of Punjab, [[Peshawar]] (1818), [[Jammu]] and [[Kashmir]] (1819). Thus Ranjit Singh put an end to more than a thousand years of Muslim rule. He also conquered the hill states north of [[Anandpur Sahib]], the largest of which was [[Kangra district|Kangra]]. |

He then spent the following years fighting the [[Pashtun people|Afghans]], driving them out of the Punjab. He also captured [[Pashtun]] territory including [[Peshawar]] (now referred to as [[North West Frontier Province]] and the [[Federally Administered Tribal Areas|Tribal Areas]]). This was the first time that Peshawari Pashtuns were ruled by [[Punjabi people|Punjabi]]s. He captured the province of [[Multan]] which encompassed the southern parts of Punjab, [[Peshawar]] (1818), [[Jammu]] and [[Kashmir]] (1819). Thus Ranjit Singh put an end to more than a thousand years of Muslim rule. He also conquered the hill states north of [[Anandpur Sahib]], the largest of which was [[Kangra district|Kangra]]. |

||

Revision as of 18:13, 8 October 2010

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (April 2009) |

| Ranjit Singh | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maharaja of Punjab | |||||

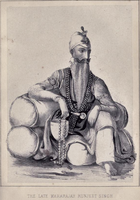

Ranjit Singh by Leopold Massard | |||||

| Reign | 12 April 1801 – 27 June 1839 | ||||

| Coronation | 12 April 1801 | ||||

| Successor | Kharak Singh | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Maha Singh | ||||

Maharaja Ranjit Singh (Template:Lang-pa) (born 13 November 1780) ruled 1799-20 June 1839; Capital city Lahore; was the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire.

Early life

Ranjit Singh was born in Gujranwala, modern-day Pakistan, into a Sikh family (according to some historians of Jatt Sikh[1] origin and others Sansi Sikh caste [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]) who were Sukerchakia misldars[11]. He belonged to Sikh clan of Northern India.[12][13] As a child he suffered from smallpox which resulted in the loss of one eye. At the time, much of Punjab was ruled by the Sikhs under a Confederate Sarbat Khalsa system, who had divided the territory among factions known as misls. Ranjit Singh's father Maha Singh was the Commander of the Sukerchakia misl and controlled a territory in west Punjab based around his headquarters at Gujranwala. After his father's death he was raised under the protection of Sada Kaur of the Kanheya Misl.[14] Ranjit Singh succeeded his father at the age of 18.[15] After several campaigns, he conquered the other misls and created the Sikh Empire.

The Maharaja

Ranjit Singh was crowned on 12 April 1801 (to coincide with Baisakhi). Sahib Singh Bedi (the name Bedi being common in Braahmans, from Veda, the name indicative of knowledge of at least one Veda and descent from Braahmans with knowledge of at least one Veda among the four), a descendant of Guru Nanak Dev, conducted the coronation [16]. Gujranwala served as his capital from 1799. In 1802 he shifted his capital to Lahore. Ranjit Singh rose to power in a very short period, from a leader of a single Sikh misl to finally becoming the Maharaja (Emperor) of Punjab.

He then spent the following years fighting the Afghans, driving them out of the Punjab. He also captured Pashtun territory including Peshawar (now referred to as North West Frontier Province and the Tribal Areas). This was the first time that Peshawari Pashtuns were ruled by Punjabis. He captured the province of Multan which encompassed the southern parts of Punjab, Peshawar (1818), Jammu and Kashmir (1819). Thus Ranjit Singh put an end to more than a thousand years of Muslim rule. He also conquered the hill states north of Anandpur Sahib, the largest of which was Kangra.

When the Foreign Minister of the Ranjit Singh's court , Fakir Azizuddin, met the British Governor-General of India, Lord Auckland, in Simla, Lord Auckland asked Fakir Azizuddin which of the Maharaja's eyes was missing, Azizuddin replied: "The Maharaja is like the sun and sun has only one eye. The splendor and luminosity of his single eye is so much that I have never dared to look at his other eye." The Governor General was so pleased with this reply that he gave his gold watch to Azizuddin.

Ranjit Singh's Empire was secular, none of the subjects were discriminated against on account of their religions.[17] The Maharaja never forced Sikhism on his subjects.

Secular Sikh Rule

The Kingdom of the Sikhs was most exceptional in that it allowed men from religions other than their own to rise to commanding positions of authority. Besides the Singh (Sikh), the Khan (Muslim) and the Misr (Hindu Brahmin) feature as prominent administrators. The Christians formed a part of the militia of the Sikhs. In 1831, Ranjit Singh deputed his mission to Simla to confer with the British Governor General, Lord William Bentinck. Sardar Hari Singh Nalwa, Fakir Aziz-ud-din and Diwan Moti Ram ― a Sikh, a Muslim and a Hindu representative ― were nominated at its head.

Externally, everyone in the Sikh kingdom looked alike; they supported a beard and covered their head, predominantly with a turban. This left visitors to the Punjab quite confused. Most foreigners arrived there after a passage through Hindustan, where religious and caste distinctions were very carefully observed. It was difficult for them to believe that though everyone in the Sarkar Khalsaji looked similar, they were not all Sikhs. The Sikhs were generally not known to force either those in their employ or the inhabitants of the country they ruled to convert to Sikhism. In fact, men of piety from all religions were equally respected by the Sikhs and their ruler. Hindu sadhus, yogis, saints and bairagis; Muslim faqirs and pirs; and Christian priests were all the recipients of Sikh largess. There was only one exception — the Sikhs viewed the Muslim clergy with suspicion. Mullahs were not looked upon kindly, as they were known to fan fanaticism[18].

In their conquests, the Sikhs never perpetrated atrocities as by invaders into the sub-continent. It was true that the Sikhs held a grudge against the Afghans for the atrocities they had perpetrated, over decades, against them. Before them, the Mughals had hunted down the Sikhs like animals in the field. Every Sikh carried a price on his head. The Afghans had caused havoc and mayhem in the Punjab during the lifetime of both Ranjit Singh’s father and grandfather. Despite that, during the rule of the Sikhs there were no reports of torture of the kind routinely inflicted upon the Sikhs by some of the Muslim rulers of Hindustan and subsequently by the Afghan invaders. The Sikhs were reportedly a most tolerant nation. According to Masson, a deserter from the British India Army who was to later become a Political Agent for the East India Company and stationed in the Kingdom of Kabul:

“At present, flushed by a series of victories, they (the Sikhs) have a zeal and buoyancy of spirit amounting to enthusiasm; and with the power of taking the most exemplary revenge, they have been still more lenient than the Mahomeddan were ever towards them”[19].

As a community, the Sikhs were as well known for their religious tolerance as the Mohammedans were notorious for their intolerance. A British Agent, Alexander Burnes, traveled extensively through the Punjab during Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s rule, narrates the following incident, which occurred at the royal stud farm at Puttee as being illustrative of the national character of the Sikhs:

“The horses were attacked with an epidemic disease from which a Mohammedan, who resides in a neighboring sanctuary, is believed to have cured them. Though a Mohammedan the Sikhs repaired and beautified his temple, which is now a conspicuous white building that glitters in the sun. I have always observed the Sikhs to be most tolerant in their religion…”[20]

The Sikhs were never accused of the routine inhuman behavior attributed to the Muslims. In fact, they made every attempt not to offend the prejudices of Mohammedans noted Baron von Hügel, the famous German traveler[21], yet the Sikhs were referred to as being harsh. In this regard, Masson’s explanation is perhaps the most pertinent:

“Though compared to the Afghans, the Sikhs were mild and exerted a protecting influence, yet no advantages could compensate to their Mohaomedan subjects, the idea of subjection to infidels, and the prohibition to slay kine, and to repeat the azan, or summons to prayer”[22].

The sanctity and inviolability of the cow in India was well entrenched in Hindu society long before Muslim invasions. This became more so with the introduction of Islamic culture into India. “The Muslim invaders were beef eaters and killers of cows, and thus the sanctity of the cow became a rallying point for Hindu resistance against the spread of Islam.” Cattle were initially the dominant commodity and gotra (cow pen) came to signify the “endogamous kinship groups” [23]. Sikhism was a revolt against the dominance of the intolerant Islamic rulers and the need to fight them with raising of martial creed. One feature of Hinduism, which did carry over into Sikhism was a respect for the sanctity of the cow. The ban on cow slaughter was universally imposed in the Sarkar Khalsaji. So strictly was this enforced that a visitor to the Kingdom of the Sikhs claimed “the cow is venerated by the Sikhs, even more than by the Hindus” [24].

The British had concealed their consumption of beef from a Hindu or Sikh and pork from Mohammedans by calling both Vilayuti huren (Hiran or Harin means deer in Indian languages), namely European venison [25]. The Revolt of 1857, ignited by the spark of discovery of cartridges that soldiers were made to open with mouths being greased with pork and beef fat, was to teach the British not to play with religious sentiment of the indigenous population — overtly or covertly.

Unlike the Muslims, the Sikhs never razed places of worship to the ground belonging to the enemy. The Sikhs were utilitarian in their approach. Marble plaques removed from Jahangir’s tomb at Shahdera were used to embellish the Baradari inside the Fort of Lahore, while most of the mosques were left intact. Forts were destroyed however, these too were often rebuilt ― the best example being the Bala Hissar in Peshawar, which was destroyed by the Sikhs in 1823[26] and rebuilt by them in 1834 [27].

Gurdwaras built by Maharaja Ranjit Singh

At the Harmandir Sahib, much of the present decorative gilding and marblework date back from the early 19th century. The gold and intricate marble work were conducted under the patronage of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Maharaja of the Punjab. The Sher-e-Punjab (Lion of the Punjab) was a generous patron of the shrine and is remembered with much affection by the Sikhs. Maharaja Ranjit Singh deeply loved and admired the teachings of the Tenth Guru of Sikhism Guru Gobind Singh, thus he promoted the teachings of the Dasam Granth (the Tenth Granth) and built two of the most sacred temples in Sikhism. These are Takht Sri Patna Sahib, the birth place of Guru Gobind Singh, and Takht Sri Hazur Sahib, the place where Guru Gobind Singh took his final rest or mahasamadhi, in Nanded, Maharashtra in 1708.

Generals of Maharaja

Ranjit Singh encircled himself with an array of strong generals and soldiers. They were men from different clans, castes and regions

These included:

- Hari Singh Nalwa

- Dewan Mokham Chand

- Jassa Singh Ahluwalia and his son[28] Fateh Singh Ahluwalia

- Veer Singh Dillon later Jallaha of Gurdaspore

- Sawan Mal

- Sirdar Gulab Singh Pahuwindia

- Sham Singh Attariwala

- Sardar Sangat Singh Saini

- Sher Singh

- Shaikh Elahi Bakhsh [29]

- General Ghause Khan (Mian Ghausa)[30]

- Sultan Mahmud Khan (Son of Ghause Khan)[31]

- Zorawar Singh

- Chattar Singh Attariwalla

- Balbhadra Kunwar - Gorkhali General who served for Ranjit Singh after the Anglo-Gorkha war (1814–1816).

- Mahan Singh Mirpuri

- Misr Diwan Chand

Among his European Mercenary Generals were:

- Jean-François Allard

- Jean-Baptiste Ventura - Italian (Modena)

- Paolo Di Avitabile - Italian (Naples)

- Claude August Court - French

Americans of note:

- Josiah Harlan - American general and later governor of Gujrat

- Alexander Gardner - American (Scotch - Irish)

Conquests

Ranjit Singh's earliest conquests as a young misldar (baron) were effected by defeating his coreligionists, the heads of other Sikh Sardaris (popularly known as the Misls). By the end of his reign, however, he had conquered vast tracts of territory strategically juxtaposed between the limits of British India to the left and the powerful Afghan Empire to the right. The land that eventually became the Kingdom of the Sikhs had been ruthlessly subjected to the worse kind of atrocities by invading armies coming through the Khyber Pass into the Indian sub-continent, over eight centuries.

In 1799, Ranjit Singh captured Lahore and made it his Capital. After the capture of Lahore, Ranjit Singh rapidly annexed the rest of the Punjab, the land of the five rivers. Having accomplished this, he extended his empire further north and west to include the Kashmir mountains and other Himalayan kingdoms, the Sind Sagar Doab, the Pothohar Plateau and trans-Indus regions right up to the foothills of the Sulaiman and Hindu Kush mountains.

Ranjit Singh took Amritsar from the Bhangi Sardari and followed this with the more difficult conquest of Kasur, the fabled twin city of Lahore, from the Pathans.[32] With the conquest of Multan the whole Bari Doab came under his sway.[33] In the year 1819, Ranjit Singh successfully annexed Kashmir[34]. This was followed by subduing the Kashmir mountains, west of the river Jhelum (today, Hazara in Pakistan and Pakistan Occupied Kashmir)[35]. Ranjit Singh built his empire by making deep inroads into the Kingdom of Kabul, defeating the Pashtun militia and the tribes inhabiting the Sindh Sagar Doab and trans-Indus regions.[36]

The most significant encounters between the Sarkar Khalsaji and the Afghans were fought in 1813, 1823, 1834 and in 1837. In 1813, Ranjit Singh's general Dewan Mokham Chand led the Sikh forces against the Afghan forces of Shah Mahmud led by Fateh Khan Barakzai. Following this encounter, the Afghans lost their stronghold at Attock. Subsequently, the Pothohar plateau, the Sindh Sagar Doab and Kashmir came under Sikh rule. In 1823, Ranjit Singh defeated a large army of Yusafzai tribesmen north of the Kabul river, while the presence of his Sikh general, Hari Singh Nalwa prevented the entire Afghan army from crossing this river and going to the aid of the Yusafzais at Nowshera. This defeat led to the gradual loss of Afghan power in the trans-Indus region. In 1834, when the forces of the Sarkar Khalsaji marched into Peshawar, the ruling Barakzais simply fled the place without offering a fight.[37]. In April 1837, the real power of Maharaja Ranjit Singh came to the fore when his commander-in-chief, Hari Singh Nalwa, kept the entire army of Amir Dost Mohammad Khan, the Wali of Kabul, at bay, with a handful of forces till reinforcements arrived from Lahore over a month after they were requisitioned[38].

Geography of the Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was also known as Punjab, the Sikh Raj, and Sarkar Khalsaji[39], was a region straddling the border into modern-day People's Republic of China and Islamic Republic of Afghanistan then popularly referred to as the Kingdom of Cabul[40]. The name of the region "Punjab" or "Panjab", comprises two words "Punj/Panj" and "Ab", translating to "five" and "water" in Persian. When put together this gives a name meaning "the land of the five rivers", coined due to the five rivers that run through the Punjab. Those "Five Rivers" are Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Chenab and Jhelum, all tributaries of the river Indus, home to the Indus Valley Civilization that perished 3000 years ago. Punjab has a long history and rich cultural heritage. The people of the Punjab are called Punjabis and they speak a language called Punjabi. The following modern day political divisions made up the historical Sikh Empire:

- Punjab region till Multan in south [41]

- Punjab, India

- Punjab, Pakistan

- Haryana, India. Including Chandigarh.

- Himachal Pradesh, India

- Kashmir, conquered in 1818, India/Pakistan/China [42][43]

- Khyber Pass, Afghanistan/Pakistan[45][46]

- Parts of Western Tibet (1841), China[51]

Legacy and aftermath

After Maharaja Ranjit Singh died in 1839, after a reign of nearly forty years, leaving seven sons by different queens. He was cremated. His ceremony was performed by both Sikh and Hindu priests, his wife Maharani Mahtab Devi Sahiba, the Princess of Kangra, daughter of Maharaja Sansar Chand, the Empress of Punjab, committed Sati with Ranjit's body as Ranjit's head lay in her lap, some of the other wives also joined her and committed Sati.[52] The throne went to his eldest son Kharak Singh, who was not entirely fit and prepared to rule such a vast empire. Some historians believe that the other heirs would have forged an even more durable, independent and powerful empire, had they come to the throne before Kharak Singh. However, the empire began to crumble due to poor governance and political infighting among his heirs. The princes died through internal plots and assassinations, while the nobility struggled to maintain power [53].

In 1845 after the First Anglo-Sikh War, Ranjit Singh's Empire was defeated and all major decisions were managed by the British East India Company. The Army of Ranjit Singh was reduced, under the peace treaty with the British, to a nominal force. Those who gave the stiffest resistance to the British were severely punished and their wealth confiscated. Eventually, Ranjit Singh's youngest son Dalip Singh, was crowned to the throne of Punjab in 1843 succeeding his brother, Maharajah Sher Singh. In 1849, at the end of the Second Anglo Sikh War, it was annexed by the British India from Dalip. Thereafter, the British took, Maharaja Dalip Singh, to England in 1854, where he was put under the protection of the Crown. Dalip Singh's mother, Maharani Jind Kaur, escaped and made her way to Nepal where she was given refuge by Sri Teen Maharaja Jung Bahadur Rana of Nepal, who then negotiated on her behalf to allow her to be reunited with her son. Maharani Jind Kaur and her son met at Spence’s Hotel, Calcutta, on the 16th January 1861, after some thirteen and half years apart. She was granted permission to come to England. A residence was taken up at No. 1 Lancaster Gate (Now No.23).

Jind Kaur stayed for a short while at Mulgrave Castle, later she was placed in the charge of an English lady at Abingdon House, Kensington. On the morning of the 1 August 1863, Maharani Jind Kaur died peacefully. Her body was temporarily housed at London’s Kensal Green Cemetery, and in the Spring of 1864, Duleep Singh left for India and arranged for the cremation of her body.

In the spring of 1864, Maharani Jind Kaur was cremated at Nasik in Bombay on the Panchvati side of the River. The authorities would not allow Dalip Singh to cremate his mother in the Punjab. On the left bank the Maharajah erected a small samadh built as a memorial in the memory of his mother. For a number of years the Kapurthala State Authorities maintained the memorial until 1924, when her remains were dug out and brought to Lahore by her granddaughter, Princess Bamba Sutherland and deposited at the Samadh of Maharajah Ranjit Singh.

Dalip Singh was converted to Christianity in his youth, upon reuniting with his mother during his adult years, he reconverted to Sikhism, he then petitioned the Crown to have his kingdom returned. He never received any justice or the respect he deserved. He died in 1893, Paris, France.

Maharajah Dalip Singh had three sons. The eldest Prince Victor was born on the 10 July 1866, followed by Prince Frederick in 1868, and then Prince Albert Edward Alexander Dalip Singh (died at the age of thirteen), who was born on the 20 August 1879.

Prince Victor Albert Jay Dalip Singh was Maharajah Dalip Singh's eldest son. He was honourable A.D.C. to Halifax, and was promoted to Captain in 1894, but his military career, however, was a shamble, his interest lied in other things and he resigned in 1898. During the First World War, he was ordered to remain in Paris and not to leave, but shortly after the war ended, Prince Victor died on the 7 June 1918, without any issue.

Princess Sophia, the youngest of the Maharajah’s daughters. On the 22 August 1948, Princess Sophia died in her sleep. Her solicitor arranged for the cremation at Golders Green on the 26 August. It was her request that her ashes be taken to India for burial.

Princess Catherine was born on the 27 October 1871, and was named Catherine Hilda Dalip Singh. Princess Catherine died peacefully in her bed on the night of Sunday 8 November 1942 at her home in Penn, aged seventy-one. The cause of death was said to be heart failure. She was cremated.

Princess Ada Irene Helen Beryl Dalip Singh, born on 25 October 1889. Tragically on the 8 October 1926, she committed suicide, local fishermen dragged her body out from the sea, off Monte Carlo. She was apparently much aggrieved with the death of her brother Prince Frederick who had died two months earlier.

Princess Pauline Alexandrina Dalip Singh, born 26 December 1887, her death was unrecorded, she disappeared in war-torn France during the Second World War

Princess Bamba Sutherland (Princess Bamba Sofia Jindan Dalip Singh) was born on the 29 September 1869 in London, a year after her brother Prince Frederick. In England, Princess Bamba began styling herself as the Queen of Punjab. She was truly her father's daughter and had her father’s rebellious nature and seemed to be the more aggrieved one among her siblings. She was the most affected at the realisation of who she was and her ancestry. She was often visited by her cousin Karl Wilhelm, grandson of Ludwig Muller, at Hilden Hall, by which time she was already dreaming of going back to India in order to die there. In his memoirs Karl Wilhelm referred to Princess Bamba as ‘the true heiress of Ranjit Singh’ meaning that she was most conscious of the actual desperate situation of the whole family. ‘She considered the Punjab and Kashmir as the lost possession of her family and was absolutely furious when the border between Pakistan and India was drawn right across the Punjab.’ In Princess Bamba’s eyes, Pakistan or India did not exist, there was just the Punjab and its capital Lahore. She met with distant relatives throughout her travels in India, trying to grasp one last glimpse of the glory that she was denied. She located the families of Wazir Ishwari Singh Katoch of Kangra and Hari Singh Nalwa, both residing in Nabha at the time. She met with the several Hindu and Sikh royal families in an attempt to prevent the division of her grandfather's empire.

On the 10 March 1957, Princess Bamba, the daughter of Maharaja Dalip Singh, died of heart failure at the age of eighty-nine. She had outlived her entire family and the final chapter of a tragic family was completed and finally laid to rest. Her funeral was conducted in a Christian ceremony in Lahore. Her rites witnessed by a select few Pakistani dignitaries, the Pakistani authorities did not allow for any of her distant relatives to attend, Sikh or Hindu, nor were any Sikhs in Pakistan allowed to attend her rites, thus there were sadly no Sikhs were present at Princess Bamba’s funeral, the last of Dalip Singh's line.

ca. 1835-40

Maharaja Ranjit Singh is remembered for uniting the Punjab as a strong nation and his possession of the Koh-i-noor diamond. Ranjit Singh willed the Koh-i-noor to Jagannath Temple in Puri, Orissa while on his deathbed in 1839.[52] His most lasting legacy was the golden beautification of the Harmandir Sahib, most revered Gurudwara of the Sikhs, with marble and gold, from which the popular name of the "Golden Temple" is derived.

He was also known as Sher-e-Punjab which means the Lion of Punjab and is considered one of the 3 Lions of modern India, the most famous and revered heroes in Indian subcontinent's history. While Emperor Rajaraja Chola and Ashoka were the 2 most powerful Indian kings of history, they are not named among the 3 Lions. The other 2 Lions are Rana Pratap Singh of Mewar and Chhatrapati Shivaji, the legendary Maratha ruler. The title of Sher-e-Punjab is still widely used as a term of respect for a powerful man.

Captain Murray's memoirs on Maharaja Ranjit Singh's character:

Ranjit Singh has been likened to Mehmet Ali and to Napoleon. There are some points in which he resembles both; but estimating his character with reference to his circumstances and positions, he is perhaps a more remarkable man than either. There was no ferocity in his disposition and he never punished a criminal with death even under circumstances of aggravated offense. Humanity indeed, or rather tenderness for life, was a trait in the character of Ranjit Singh. There is no instance of his having wantonly imbused his hand in blood." [54][55]

Many famous folk stories about Maharaja portray a leader and the inspiration Maharaja Ranjit Singh was. In one famous incident, when Maharaja was about to cross the badly flooded river near Attock (now in Pakistan and called Kabul River). One of Maharaja's generals reported this fact to Maharaja, saying that the river cannot be crossed and it is now an Atak (an obstacle in Hindi) for us. Maharaja retorted "eh Attock uhna lai atak hai, jehna de dillan wich atak hai" or "This river Attock is an obstacle for those, who have obstacles in their hearts", then crossed the river successfully. The army and other generals followed his lead.

Another famous folk story about Maharaja is that he was accidentally hit by a stone thrown by a 5 year old boy, who actually wanted to hit a fruit tree to knock down some of its fruit. When he was brought before Maharaja, Ranjit Singh gave him a gold coin. He said, "How can I punish him for hitting me with a stone, when this tree will give him fruit for the same?"

Further reading

- Umdat Ut Tawarikh by Sohan Lal Suri, Published by Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar .

- The Real Ranjit Singh by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 01 Jan 2001 , 2nd ed. First ed. published 1965 Pakistan.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: First Death Centenary Memorial, by St. Nihal Singh. Published by Languages Dept., Punjab, 1970.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his times, by J. S. Grewal, Indu Banga. Published by Dept. of History, Guru Nanak Dev University, 1980.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Harbans Singh. Published by Sterling, 1980.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by K. K. Khullar. Published by Hem Publishers, 1980.

- The reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh: structure of power, economy and society, by J. S. Grewal. Published by Punjab Historical Studies Dept., Punjabi University, 1981.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, as patron of the arts, by Ranjit Singh. Published by Marg Publications, 1981.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Politics, Society, and Economy, by Fauja Singh, A. C. Arora. Published by Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, 1984.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his Times, by Bhagat Singh. Published by Sehgal Publishers Service, 1990. ISBN 81-85477-01-9.

- History of the Punjab: Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Shri Ram Bakshi. Published by Anmol Publications, 1991.

- The Historical Study of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Times, by Kirpal Singh. Published by National Book Shop, 1994. ISBN 81-7116-163-4.

- An Eyewitness account of the fall of Sikh empire: memories of Alexander Gardner, by Alexander Haughton Campbell Gardner, Baldev Singh Baddan, Hugh Wodehouse Pearse. Published by National Book Shop, 1999. ISBN 81-7116-231-2.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the Last to Lay Arms: The Last to Lay Arms, by Kartar Singh Duggal. Published by Abhinav Publications, 2001. ISBN 81-7017-410-4.

- Fauj-i-khas Maharaja Ranjit Singh and His French Officers, by Jean Marie Lafont. Published by Guru Nanak Dev University, 2002. ISBN 81-7770-048-0.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, by Mohinder Singh, Rishi Singh, Sondeep Shankar, National Institute of Panjab Studies (India). Published by UBS Publishers' Distributors with National Institute of Panjab Studies, 2002. ISBN 81-7476-372-4,.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh: Lord of the Five Rivers, by Jean Marie Lafont. Published by Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-566111-7.

See also

- Baradari of Ranjit Singh

- History of Punjab

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Generals

- Preminder Singh Sandhawalia

- Sikh Empire

References

- ^ http://books.google.co.in/books?id=7iOsNUZ2MXgC&pg=PA459&dq=ranjit+singh+sansi&as_brr=3&ei=3cgzS9zWGInolQTk4e2rAQ&cd=2#v=onepage&q=sindhanwalia%20sansi&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=kxtEFA5qqR8C&pg=PA12&dq=ranjit+singh+sansi&as_brr=3&ei=3cgzS9zWGInolQTk4e2rAQ&cd=6#v=onepage&q=ranjit%20singh%20sansi&f=false

http://www.google.co.uk/books?id=-UkBAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Henry+Thoby+Prinsep,&as_brr=1&cd=4#v=onepage&q=desoo&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=KNJ_FMzw72AC&pg=PA167&dq=ranjit+singh+sansi&as_brr=3&ei=3cgzS9zWGInolQTk4e2rAQ&cd=9#v=onepage&q=ranjit%20singh%20sansi&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=Q0ABAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA15&dq=ranjit+singh+sansi&as_brr=3&ei=3cgzS9zWGInolQTk4e2rAQ&cd=10#v=onepage&q=sindhanwalia&f=false

http://books.google.co.in/books?id=w_YRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA357&dq=ranjit+singh+sansi&lr=&as_brr=3&ei=0c4zS6mUAqeKlQSa1qDKAQ&cd=11#v=onepage&q=ranjit%20singh%20sansi&f=false - ^ "Two, Ranjit Singh who seemingly got “total ascendancy” in Punjab was not a Jat but a Sansi...", Sangat Singh, MCLEOD AND FENECH AS SCHOLARS ON SIKHISM AND MARTYRDOM, Presented in International Sikh conferences 2000 , www.globalsikhstudies.net

- ^ Sir Lepel Griffin, Punjab Chiefs, Vol. 1, p 219"...and from Sansi the Sindhanwalias and the Sansis have a common descent. The Sansis were the thievish and degraded tribe [sic] and the house of Sindhanwalia naturally feeling ashamed of its Sansi name invented a romantic story to account for it. But the relationship between the nobles and the beggars, does not seem the less certain and if history of Maharaja Ranjit Singh is attentively considered it will appear that much his policy and many of his actions had the true Sansi complexion"

- ^ The Sansis of Punjab; a Gypsy and De-notified Tribe of Rajput Origin, Maharaja Ranjit Singh- The Most Glorious Sansi, pp 13, By Sher Singh, 1926-, Published by , 1965, Original from the University of Michigan

- ^ Tribalism in India, pp 160, By Kamaladevi Chattopadhyaya, Edition: illustrated, Published by Vikas, 1978, Original from the University of Michigan

- ^ Sociological Bulletin,pp 97, By Indian Sociological Society, Published by Indian Sociological Society., 1952

- ^ Indian Librarian edited by Sant Ram Bhatia,pp 220, Published by, 1964Item notes: v.19-21 1964-67, Original from the University of Michigan

- ^ The Sikhs in History, pp 92, By Sangat Singh, Edition: 2, Published by S. Singh, 1995, Original from the University of Michigan

- ^ Some Aspects of State and Society Under Ranjit Singh, pp 5 By Fauja Singh, Published by Master Publishers, 1981, Original from the University of Michigan

- ^ Preminder Singh Sandhawalia (1999). Noblemen and Kinsmen History of a Sikh Family: History of a Sikh Family. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 81-215-0914-9

- ^ a b Jean-Marie Lafont, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lord of the Five Rivers. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- ^ Preminder Singh Sandhawalia (1999). Noblemen and Kinsmen History of a Sikh Family: History of a Sikh Family. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 8121509149.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jean-Marie Lafont, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lord of the Five Rivers. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- ^ Gardner, Haughton Campbell Gardner (1898). Soldier and Traveller: Memoirs of Alexander Gardner. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. p. 298.

- ^ Heath 2005, p. 3

- ^ "Ranjit Singh, Maharaja", Sikh Cyber Museum

- ^ K.S. Duggal, Ranjit Singh: A Secular Sikh Sovereign, Abhinav Publications (1989) ISBN 81-7017-244-6)

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 11-12, ISBN 81-7304-785-5

- ^ Masson, Charles. 1842. Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, 3 v. London: Richard Bentley, (1) 435

- ^ National Archives of India (New Delhi) Foreign Secret Consultation, 6 June 1833, No. 5

- ^ Hügel, Baron (1845) 2000. Travels in Kashmir and the Panjab, containing a Particular Account of the Government and Character of the Sikhs, tr. Major T.B. Jervis. rpt, Delhi: Low Price Publications, p. 151

- ^ Masson, Charles. 1842. Narrative of Various Journeys in Balochistan, Afghanistan and the Panjab, 3 v. London: Richard Bentley (1) 37

- ^ Lodrick, D.O. 1981. Sacred Cows, Sacred Places. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 145

- ^ Vigne, G.T., 1840. A Personal Narrative of a Visit to Ghuzni, Kabul, and Afghanistan, and a Residence at the Court of Dost Mohammed…, London: Whittaker and Co. p. 246

- ^ Vigne, G.T., 1840. A Personal Narrative of a Visit to Ghuzni, Kabul, and Afghanistan, and a Residence at the Court of Dost Mohammed…, London: Whittaker and Co. p. 302

- ^ National Archive of India (New Delhi) Foreign Secret Consultation, 29 October 1824, No. 9

- ^ Sohan Lal Suri, 19th century. Umdat-ut-tawarikh Daftar III Parts (1-5), tr. V.S. Suri, (1961), Amritsar: Guru Nanak Dev University (2002), (III-2) f. 217)

- ^ Encyclopaedic History of Indian Freedom Movement By Om Prakash Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2001 Published by Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2001 Page 201

- ^ http://www.thesikhencyclopedia.com/muslims-rulers-and-sufi-saints/ilahi-bakhsh.html

- ^ http://www.thesikhencyclopedia.com/muslims-rulers-and-sufi-saints/ghaus-khan.html

- ^ http://www.thesikhencyclopedia.com/muslims-rulers-and-sufi-saints/sultan-mahmud-khan.html

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, p. 27, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, p. 40-1, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 44-6, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 77-90, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 105-131, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 161-3; 161, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 177-217, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, p. 10, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Elphinstone, M. (1815) 1972, An account of the Kingdom of Caubul, rpt, 3rd edition,Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2 vols.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 40-41, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Marshall 2005, p. 116

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 43-46, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Ben Cahoon. "Pakistan Princely States". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion, (Docherty,p.187)

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 177-220, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ The Khyber Pass: A History of Empire and Invasion, (Docherty,p.185-187)

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 41-2; 153-176, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Nalwa, V. (2009), Hari Singh Nalwa - Champion of Khalsaji, New Delhi: Manohar, pp. 77-104, ISBN 81-7304-785-5.

- ^ Bennett-Jones, Owen; Singh, Sarina, Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway Page 199

- ^ Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the last to lay arms, (Duggal,p.133)

- ^ a b The Real Ranjit Singh by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 01 Jan 2001 , 2nd ed.

- ^ The Death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh V&A Museum.

- ^ Murray (Captain); History of The Punjab, Vol. II, p. 174 (Reprint, Patiala (1970)

- ^ Gurdashan Singh Dhillon"The Sikh Rule and Ranjit Singh", A Gateway to Sikhism

Bibliography

- Heath, Ian (2005), The Sikh Army 1799-1849, Osprey Publishing (UK), ISBN 1-84176-777-8

- Marshall, Julie (2005), Britain and Tibet 1765-1947: A Select Annotated Bibliography of British Relations with Tibet and the Himalayan States including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan Revised and Updated to 2003 (Hardcover), Routledge; Rev Upd edition, ISBN 978-0415336475

- The Real Ranjit Singh by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 01 Jan 2001 , 2nd ed. First ed. published 1965 Pakistan.

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh, Lord of the Five Rivers, By Jean-Marie Lafont. (Oxford University Press. Date:2002, ISBN 0-19-566111-7).

- Noblemen and Kinsmen History of a Sikh Family: History of a Sikh Family, By Preminder Singh Sandhawalia (Author), (Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. Date:1999, ISBN 81-215-0914-9).

External links

- True Account of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

- Ranjit Singh

- Biography of the Sher-E-Punjab

- Official government of Pakistan cultural history article on Maharaja Ranjit Singh

![]() Media related to Sikh Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sikh Empire at Wikimedia Commons

- Genealogy

- RoyalArk on Punjab's dynasty, includes extensive bios

- Genealogy of Lahore (Princely State) Queensland University

- Biographies

- Ranjit Singh profile from sikh-history.com

- Ranjit Singh military career profile

- Extra profile from sikh-history.com

- Foreign officers in Ranjit Singh's Court

- Detailed article on Ranjit Singh's Army

- Ajitweely

- Article on Maharaja Ranjit Singh Museum

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)