Fall of Singapore: Difference between revisions

and finally. |

|||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

Wavell subsequently told Percival that the ground forces were to fight on to the end, and that there should not be a general surrender in Singapore.<ref name="Smith" /> |

Wavell subsequently told Percival that the ground forces were to fight on to the end, and that there should not be a general surrender in Singapore.<ref name="Smith" /> |

||

{{Quote box|''My attack on Singapore was a bluff – a bluff that worked. I had 30,000 men and was outnumbered more than three to one. I knew that if I had to fight for long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting.''|source = – [[Tomoyuki Yamashita]] <sub>Shores 1992, p. 383.</sub>|width =35%| align =right}} |

{{Quote box|''My attack on Singapore was a bluff – a bluff that worked. I had 30,000 men and was outnumbered more than three to one. I knew that if I had to fight for long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting.''|source = – [[Tomoyuki Yamashita]] <sub>Shores 1992, p. 383.</sub>|width =35%| align =right}} |

||

Revision as of 23:32, 21 October 2010

| Battle of Singapore | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Pacific War (World War II) | |||||||

Lt Gen. Arthur Percival, led by a Japanese officer, walks under a flag of truce to negotiate the capitulation of Allied forces in Singapore, on 15 February 1942. It was the largest surrender of British-led forces in history. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Malaya Command: (limited involvement) |

Twenty-Fifth Army | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 85,000 | 36,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

9,500 killed 5,000 wounded 120,000 captured[1] |

1,713 killed 2,772 wounded[2] | ||||||

Template:Fix bunching The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II when the Empire of Japan invaded the Allied stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in South East Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East". The fighting in Singapore lasted from 31 January 1942 to 15 February 1942.

It resulted in the fall of Singapore to the Japanese, and the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history.[2] About 80,000 British, Australian and Indian troops became prisoners of war, joining 50,000 taken by the Japanese in the Malayan campaign. Britain's Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the ignominious fall of Singapore to the Japanese the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British history.[3]

Background

The Allies had imposed a trade embargo on Japan in response to its continued campaigns in China. Seeking alternate sources of necessary materials for its Pacific War against the Allies, Japan invaded Malaya.[4] Singapore, to the south, was connected to Malaya by the Johor–Singapore Causeway. The Japanese saw it as a port which could be used as a launch pad against other Allied interests in the area, and to consolidate the invaded territory.

The Japanese also sought to eliminate those in Singapore who were supporting China in the Second Sino-Japanese War. The ethnic Han Chinese in Malaya and Singapore had through financial and economic means aided the Chinese defence against the Japanese. The effort however suffered from factionalism, as the aid was split between the opposing sides of the ongoing Chinese Civil War. Despite the Xi'an Incident, which had supposedly united both the ruling Kuomintang Party and the Communist Party of China against the Japanese, fighting between them was still common. The funds were further split as some was used for humanitarian relief of the Chinese civilian population in addition to aid to the Kuomintang and Communist party of China. Such aid had contributed to the stalling of the Japanese advance in China. Tan Kah Kee was a prominent philanthropist within the Singaporean Chinese community, and was a major financial contributor, with many relief efforts organised in his name. Aid to China from the population of Singapore in its several forms became part of Imperial Japan's casus belli motivation to attack Singapore through Malaya.

Invasion of Malaya

| History of Singapore |

|---|

|

|

|

The Japanese Twenty-Fifth Army invaded Malaya from Indochina, moving into northern Malaya and Thailand by amphibious assault on 8 December 1941. This was virtually simultaneous with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which was meant to deter the United States from intervening in Southeast Asia. Japanese troops in Thailand coerced the Thai government to let the Japanese use Thai military bases for the invasion of other nations in Southeast Asia and then proceeded overland across the Thai–Malayan border to attack Malaya. At this time, the Japanese began bombing of sites all over Singapore, and air raids were conducted on Singapore from this point onwards, although anti-aircraft fire kept most of the Japanese bombers from totally devastating the island as long as ammunition was available.

The Japanese Army was resisted in northern Malaya by III Corps of the Indian Army and several British Army battalions. Although the 25th Army was outnumbered by Allied forces in Malaya and Singapore, Japanese commanders concentrated their forces. The Japanese were superior in close air support, armour, coordination, tactics and experience. Moreover, the British forces repeatedly allowed themselves to be outflanked, believing—despite repeated flanking attacks by the Japanese—that the Malay jungle was impassable. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force was more numerous, and better trained than the second hand assortment of untrained pilots and inferior allied equipment remaining in Malaya, Borneo and Singapore. Their superior fighters, especially the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, helped the Japanese to gain air superiority. The Allies had no tanks and few armoured vehicles, which put them at a severe disadvantage.

The battleships HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse and four destroyers (Force Z) reached Malaya before the Japanese began their air assaults. This force was thought to be a deterrent to the Japanese. Japanese aircraft, however, sank the capital ships, leaving the east coast of the Malayan peninsula exposed and allowing the Japanese to continue their amphibious landings.

Japanese forces quickly isolated, surrounded, and forced the surrender of Indian units defending the coast. They advanced down the Malayan peninsula overwhelming the defences, despite numerical inferiority. The Japanese forces also used bicycle infantry and light tanks allowing swift movement through the jungle.

Although more Allied units, including some from the Australian 8th Division, joined the campaign, the Japanese prevented the Allied forces from regrouping, overran cities, and advanced towards Singapore. The city was an anchor for the operations of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM), the first Allied joint command of World War II. Singapore also controlled the main shipping channel between the Indian and the Pacific Oceans.

On 31 January the last Allied forces left Malaya and Allied engineers blew up the causeway linking Johore and Singapore. Japanese infiltrators – many disguised as Singaporean civilians – crossed the Straits of Johor in inflatable boats soon afterwards.

Preparations

During the weeks preceding the invasion, the Allied forces suffered a number of both subdued and openly disruptive disagreements amongst its senior commanders,[5] as well as pressure from the Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies.[6] Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival, commander of the garrison, had 85,000 soldiers, the equivalent, on paper, of just over four divisions. There were about 70,000 front-line troops in 38 infantry battalions – 13 British, 6 Australian, 17 Indian, and 2 Malayan – and 3 machine-gun battalions. The newly-arrived British 18th Infantry Division under Major-General Merton Beckwith-Smith was at full strength, but lacked experience and appropriate training; most of the other units were under strength, a few having been amalgamated due to heavy casualties, as a result of the mainland campaign. The local battalions had no experience and in some cases no training.[7]

Percival gave Major-General Gordon Bennett's two brigades from the Australian 8th Division responsibility for the western side of Singapore, including the prime invasion points in the north-west of the island. This was mostly mangrove swamp and jungle, broken by rivers and creeks. In the heart of the "Western Area" was RAF Tengah, Singapore's largest airfield at the time. The Australian 22nd Brigade was assigned a 10-mile (16 km) wide sector in the west, and the 27th Brigade had responsibility for a 4,000-yard (3,650 m) zone just west of the Causeway. The infantry positions were reinforced by the recently-arrived Australian 2/4th Machine-Gun Battalion. Also under Bennett's command was the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade.

The Indian III Corps under Lieutenant-General Sir Lewis Heath, including the Indian 11th Infantry Division, (Major-General B. W. Key), the British 18th Division and the 15th Indian Infantry Brigade, was assigned the north-eastern sector, known as the "Northern Area". This included the naval base at Sembawang. The "Southern Area", including the main urban areas in the south-east, was commanded by Major-General Frank Keith Simmons. His forces comprised about 18 battalions, including the Malayan 1st Infantry Brigade, the Straits Settlements Volunteer Force Brigade and Indian 12th Infantry Brigade.

From aerial reconnaissance, scouts, infiltrators and high ground across the straits such as the Sultan of Johore's palace, the Japanese commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita and his staff gained excellent knowledge of the Allied positions. From 3 February the Allies were shelled by Japanese artillery.

Japanese air attacks on Singapore intensified over the next five days. Air and artillery bombardment intensified, severely disrupting communications between Allied units and their commanders and affecting preparations for the defence of the island.

Singapore's famous large-calibre coastal guns – which included one battery of three 15-inch (381 mm) guns and one with two 15-inch (381 mm) guns – were supplied mostly with armour-piercing (AP) shells and few high explosive (HE) shells. AP shells were designed to penetrate the hulls of heavily armoured warships and were ineffective against personnel. It is commonly said that the guns could not fire on the Japanese forces because they had been designed only to face south, but this is not so, although the lack of H.E. ammunition was an error of the same sort and possibly due to the belief that an invading army couldn't come from the north. Although placed to fire on enemy ships to the south, most of the guns could turn northwards and they did fire at the invaders. Military analysts later estimated that if the guns had been well supplied with HE shells the Japanese attackers would have suffered heavy casualties, but the invasion would not have been prevented by this means alone.

Yamashita had just over 30,000 men from three divisions: the Imperial Guards Division under Lieutenant-General Takuma Nishimura, the 5th Division under Lieutenant-General Takuro Matsui and the 18th Division under Lieutenant-General Renya Mutaguchi. The elite Imperial Guards units included a light tank brigade.

Japanese landings

Blowing up the causeway had delayed the Japanese attack for over a week. At 8.30pm on 31 January, Australian machine gunners opened fire on vessels carrying a first wave of 4,000 troops from the 5th and 18th Divisions towards Singapore island. The Japanese assaulted Sarimbun Beach, in the sector controlled by the Australian 22nd Brigade under Brigadier Harold Taylor.

Fierce fighting raged all day, but eventually the increasing Japanese numbers – and the superiority of their artillery, aircraft and military intelligence – began to take their toll. In the northwest of the island they exploited gaps in the thinly spread Allied lines such as rivers and creeks. By midnight the two Australian brigades had lost communications with each other and the 22nd Brigade was forced to retreat. At 1am further Japanese troops were landed in the northwest of the island and the last Australian reserves went in. Towards dawn on 9 February elements of the 22nd Brigade were overrun or surrounded, and the 2/18th Australian Infantry Battalion had lost more than half of its personnel.

Air war

Air cover was provided by only ten Hawker Hurricane fighters of RAF No. 232 Squadron, based at Kallang Airfield. This was because Tengah, Seletar and Sembawang were in range of Japanese artillery at Johore Bahru. Kallang Airfield was the only operational airstrip left; the surviving squadrons were withdrawn by January to reinforce the Dutch East Indies.

This fighter force performed considerably well, but was outnumbered and often outmatched by the Japanese A6M Zero – it suffered severe losses, both in the air and on the ground during February.

On 8 December, Singapore was subject to aerial bombing for the first time by long-range Japanese aircraft, such as the Mitsubishi G3M Nell and the Mitsubishi G4M Betty, based in Japanese-occupied Indochina. After this first raid, the Japanese bombings ceased throughout the rest of December, and resumed only on 1 January 1942.

During December, 51 Hurricane Mk II fighters were sent to Singapore, with 24 pilots, the nuclei of five squadrons. They arrived on 3 January 1942, by which stage the Buffalo squadrons had been overwhelmed. No. 232 Squadron was formed and No. 488 Squadron RNZAF, a Buffalo squadron converted to Hurricanes. 232 Squadron became operational on 20 January and destroyed three Ki-43s that day,[8] for the loss of three Hurricanes. However, like the Buffalos before them, the Hurricanes began to suffer severe losses in intense dogfights.

During the period 27 January–30 January, another 48 Hurricanes (Mk IIA) arrived with No. 226 Group (four squadrons) on the aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, from which they flew to airfields code-named P1 and P2, near Palembang, Sumatra in the Dutch East Indies. The staggered arrival of the Hurricanes, along with inadequate early warning systems, meant that Japanese air raids were able to destroy a large proportion of the Hurricanes on the ground in Sumatra and Singapore.

On the morning of 8 February, a number of aerial dogfights took place over Sarimbun Beach and other western areas. In the first encounter, the last ten Hurricanes were scrambled from Kallang Airfield to intercept a Japanese formation of about 84 planes, flying from Johore to provide air cover for their invasion force. In two sorties the Hurricanes shot down six Japanese planes for the loss of one of their own – they flew back to Kallang halfway through the battle, hurriedly re-fuelled, then returned to it.[9] Air battles went on over the island for the rest of the day, and by nightfall it was clear that with the few machines Percival had left, Kallang could no longer be used as a base. With his assent the remaining Hurricanes were withdrawn to Palembang, Sumatra, and Kallang became merely an advanced landing ground. No allied aircraft were seen again over Singapore, and the Japanese had full control of the skies.[10]

On the evening of 10 February, General Archibald Wavell ordered the transfer of all remaining Allied air force personnel to the Dutch East Indies. By this time Kallang Airfield was so pitted with bomb craters that it was no longer usable.

Second day

Believing that further landings would occur in the northeast, Percival did not reinforce the 22nd Brigade. During 9 February Japanese landings shifted to the southwest, where they encountered the 44th Indian Infantry Brigade. Allied units were forced to retreat further east. Bennett decided to form a secondary defensive line, known as the "Jurong Line", around Bulim, east of Tengah Airfield and just north of Jurong.

Brigadier Duncan Maxwell's Australian 27th Brigade, to the north, did not face Japanese assaults until the Imperial Guards landed at 10pm on 9 February. This operation went very badly for the Japanese, who suffered severe casualties from Australian mortars and machine guns, and from burning oil which had been sluiced into the water. A small number of Guards reached the shore and maintained a tenuous beachhead.

Command and control problems caused further cracks in the Allied defence. Maxwell was aware that the 22nd Brigade was under increasing pressure, but was unable to contact Taylor and was wary of encirclement. In spite of his brigade's success – and in contravention of orders from Bennett – Maxwell ordered it to withdraw from Kranji in the central north. The Allies thereby lost control of the beaches adjoining the west side of The Causeway.

Japanese breakthrough

The opening at Kranji made it possible for Imperial Guards armoured units to land unopposed there. Tanks with flotation equipment attached were towed across the strait and advanced rapidly south, along Woodlands Road. This allowed Yamashita to outflank the 22nd Brigade on the Jurong Line, as well as bypassing the 11th Indian Division at the naval base. However, the Imperial Guards failed to seize an opportunity to advance into the city centre itself.

On the evening of 10 February, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, cabled Wavell, saying:

I think you ought to realise the way we view the situation in Singapore. It was reported to Cabinet by the C.I.G.S. [Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Alan Brooke] that Percival has over 100,000 [sic] men, of whom 33,000 are British and 17,000 Australian. It is doubtful whether the Japanese have as many in the whole Malay Peninsula... In these circumstances the defenders must greatly outnumber Japanese forces who have crossed the straits, and in a well-contested battle they should destroy them. There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. The 18th Division has a chance to make its name in history. Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake. I rely on you to show no mercy to weakness in any form. With the Russians fighting as they are and the Americans so stubborn at Luzon, the whole reputation of our country and our race is involved. It is expected that every unit will be brought into close contact with the enemy and fight it out ...[11]

Wavell subsequently told Percival that the ground forces were to fight on to the end, and that there should not be a general surrender in Singapore.[2]

My attack on Singapore was a bluff – a bluff that worked. I had 30,000 men and was outnumbered more than three to one. I knew that if I had to fight for long for Singapore, I would be beaten. That is why the surrender had to be at once. I was very frightened all the time that the British would discover our numerical weakness and lack of supplies and force me into disastrous street fighting.

On 11 February, knowing that Japanese supplies were running perilously low, Yamashita decided to bluff and he called on Percival to "give up this meaningless and desperate resistance". By this stage the fighting strength of the 22nd Brigade – which had borne the brunt of the Japanese attacks – had been reduced to a few hundred men. The Japanese had captured the Bukit Timah area, including most of the allied ammunition and fuel and giving them control of the main water supplies.

The next day the allied lines stabilised around a small area in the south-east of the island and fought off determined Japanese assaults. Other units, including the 1st Malaya Infantry Brigade, had joined in. A Malayan platoon, led by Lt Adnan bin Saidi, held the Japanese for two days at the Battle of Pasir Panjang. His unit defended Bukit Chandu, an area which included a major allied ammunition store. Adnan was executed by the Japanese after his unit was overrun.

On 13 February, with the Allies still losing ground, senior officers advised Percival to surrender in the interests of minimising civilian casualties. Percival refused, but unsuccessfully sought authority to surrender from his superiors.

That same day military police executed a convicted British traitor, Captain Patrick Heenan, who had been an Air Liaison Officer with the Indian Army.[12] Japanese military intelligence had recruited Heenan before the war, and he had used a radio to assist them in targeting Allied airfields in northern Malaya. He had been arrested on 10 December and court-martialled in January. Heenan was shot at Keppel Harbour, on the south side of Singapore, and his body was thrown into the sea.[2]

The following day the remaining Allied units fought on; civilian casualties mounted as one million people crowded into the area still held by the Allies, and bombing and artillery fire intensified. Civilian authorities began to fear that the water supply would give out.

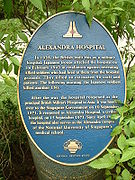

Alexandra Hospital massacre

At about 1.00pm on 14 February Japanese soldiers advanced towards the Alexandra Barracks Hospital.[13] A British lieutenant, acting as an envoy with a white flag, approached the Japanese forces but was bayoneted and killed.[14] After the Japanese troops entered the hospital, a number of patients, including those undergoing surgery at the time, were killed along with doctors and members of nursing staff.[15] The following day about 200 male staff members and patients who had been assembled and bound the previous day,[16] many of them walking wounded, were ordered to walk about 400 metres to an industrial area. Anyone who fell on the way was bayoneted. The men were forced into a series of small, badly ventilated rooms and were imprisoned overnight without water. Some died during the night as a result of their treatment.[17] The remainder were bayoneted the following morning;[18] there were only five survivors, including George Britton of the East Surrey Regiment.[19], also Hugo Hughes, who lost his right leg, and George Wort, who lost an arm, both of the Malay Regiment.[20]

The Alexandra Hospital was also known as the British Military Hospital, Singapore.

Fall of Singapore

By the morning of Chinese New Year, 15 February, the Japanese had broken through the last line of defence and the Allies were running out of food and ammunition. The anti-aircraft guns had also run out of ammunition and were unable to repel any further Japanese air attacks which threatened to cause heavy casualties in the city centre. Looting and desertion by Allied troops further added to the chaos in the city centre.[21]

At 9:30 a.m, Percival held a conference at Fort Canning with his senior commanders. Percival proposed two options. Either launch an immediate counter-attack to regain the reservoirs and the military food depots in the Bukit Timah region and drive the enemy's artillery off its commanding heights outside the town, or capitulate. All present agreed that no counter-attack was possible. Percival opted for surrender.

A deputation was selected to go to the Japanese Headquarters. It consisted of a senior Staff Officer, the Colonial Secretary and an interpreter. They set off in a motor car bearing a Union Jack and a white flag of truce towards the enemy lines to discuss a cessation of hostilities.[2] They returned with orders that Percival himself proceed with Staff Officers to the Ford Motor Factory, where General Yamashita would lay down the terms of surrender. A further requirement was that the Japanese Rising Sun Flag be hoisted over the tallest building in Singapore, the Cathay Building, as soon as possible to maximise the psychological impact of the official surrender. Percival formally surrendered shortly after 5.15pm.

The terms of the surrender included:

- The unconditional surrender of all military forces (Army, Navy and Air Force) in Singapore Area.

- Hostilities to cease at 8:30 p.m. that evening.

- All troops to remain in position until further orders.

- All weapons, military equipment, ships, planes and secret documents to be handed over intact.

- To prevent looting, etc., during the temporary withdrawal of all armed forces in Singapore, a force of 1000 British armed men to take over until relieved by the Japanese.

Earlier that day Percival had issued orders to destroy before 4 p.m. all secret and technical equipment, ciphers, codes, secret documents and heavy guns. Yamashita accepted his assurance that no ships or planes remained in Singapore. According to Tokyo's Domei News Agency Yamashita also accepted full responsibility for the lives of British and Australian troops, as well as British civilians remaining in Singapore.

Bennett, along with some of his staff officers, caused controversy when he handed command of the 8th Division to a brigadier and commandeered a small boat.[22] They eventually made their way back to Australia.

Aftermath

The Japanese Occupation of Singapore had begun. The city was renamed Syonan-to (Template:Lang-ja, literally Light-of-the-South Island). The Japanese sought vengeance against the Chinese and to eliminate anyone who held anti-Japanese sentiment. The Imperial authorities were suspicious of the Chinese because of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and killed many in the Sook Ching Massacre. The other ethnic groups of Singapore such as the Malays and the Indians were not spared. The residents would suffer great hardships under Japanese rule over the following three and a half years.

Many of the British and Australian soldiers taken prisoner remained in Singapore's Changi Prison. Many would never return home. Thousands of others were shipped on prisoner transports known as "hellships" to other parts of Asia, including Japan, to be used as forced labour on projects such as the Siam–Burma Death Railway and Sandakan airfield in North Borneo. Many of those aboard the ships perished.

The Japanese were highly successful in recruiting Indian soldiers taken prisoner. From a total of about 40,000 Indian personnel in Singapore in February 1942, about 30,000 joined the pro-Japanese "Indian National Army", which fought Allied forces in the Burma Campaign.[23] Others became POW camp guards at Changi. However, many Indian Army personnel resisted recruitment and remained POWs. An unknown number were taken to Japanese-occupied areas in the South Pacific as forced labour. Many of them suffered severe hardships and brutality similar to that experienced by other prisoners of Japan during World War II. About 6,000 of them survived until they were liberated by Australian and U.S. forces, in 1943–45.[23]

After the Japanese surrender in 1945 Yamashita was tried by a US military commission for war crimes committed by Japanese personnel in the Philippines earlier that year, but not for crimes committed by his troops in Malaya or Singapore. He was convicted and hanged in the Philippines on 23 February 1946.[2]

See also

- British Malaya Command – Order of Battle

- British Far East Command

- Japanese Order of Battle, Malayan Campaign

- British Military Hospital, Singapore

References

Bibliography

- Dixon, Norman F. On the Psychology of Military Incompetence, London, 1976

- Bose, Romen. SECRETS OF THE BATTLEBOX: The History and Role of Britain's Command HQ during the Malayan Campaign, Marshall Cavendish, Singapore 2005

- Bose, Romen. KRANJI:The Commonwealth War Cemetery and the Politics of the Dead, Singapore: Marshall Cavendish (2006)

- Kinvig, Clifford. Scapegoat: General Percival of Singapore, London (1996) ISBN 0241105838

- Smyth, John George. Percival and the Tragedy of Singapore, MacDonald and Company, 1971, ASIN B0006CDC1Q

- Thompson, Peter. The Battle for Singapore, London (2005) ISBN 0749950684 HB

- Seki, Eiji. Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental (2006) ISBN 1905246285; (cloth) [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007 – previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Shores, Christopher F; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho. Bloody Shambles: The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942, London: Grub Street (2007)

- Shores, Christopher F; Cull, Brian; Izawa, Yasuho. Bloody Shambles, The First Comprehensive Account of the Air Operations over South-East Asia December 1941 – April 1942 Volume One: Drift to War to the Fall of Singapore. London: Grub Street Press. (1992) ISBN 094881750X

- Smith, Colin. Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II Penguin (2005) ISBN 0670913413

- Thompson, P. The Battle for Singapore, The True Story of the Greatest Catastrophe of World War II, London (2005) ISBN 0749950994

Notes

- ^ Altogether the Allied forces lost 7,500 killed, 10,000 wounded and about 120,000 captured for the entire Malayan Campaign

- ^ a b c d e f Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin Group. ISBN ISBN 0-141-01036-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Churchill, Winston (1986). The Hinge of Fate, Volume 4. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 81. ISBN 0395410584

- ^ Thompson, p. 92–94.

- ^ Thompson, p. 103–130.

- ^ Thompson, p. 60–61.

- ^ "The Malayan Campaign 1941". Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ^ Cull, Brian and Sortehaug, Brian and Paul. Hurricanes Over Singapore: RAF, RNZAF and NEI Fighters in Action Against the Japanese Over the Island and the Netherlands East Indies, 1942. London: Grub Street, 2004. (ISBN 1-904010-80-6), pp. 27–29. Note: 64 Sentai lost three Ki-43s and claimed five Hurricanes.

- ^ "Hawker Hurricane shot down on 8 February 1942". Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- ^ Percival's Despatches

- ^ The Second World War. Vol. IV. By Winston Churchill.

- ^ Peter Elphick, 2001, "Cover-ups and the Singapore Traitor Affair" Access date: 5 March 2007.

- ^ Thompson, p. 476.

- ^ Thompson, p. 477.

- ^ Thompson, p. 476–478.

- ^ Thompson, p. 477–478.

- ^ Thompson, p. 478.

- ^ "Alexandra Massacre". Archived from the original on 18 October 2005. Retrieved 7 December 2005.

- ^ George Britton, personal recollection 2009

- ^ Hugo Hughes' war diary, written in Changi

- ^ Nicholas Rowe, Alistair Irwin (21 September 2009). "Generals At War". 60 minutes in. National Geographic Channel.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|began=,|episodelink=,|serieslink=,|ended=,|transcripturl=, and|seriesno=(help); Missing or empty|series=(help); Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - ^ Lieutenant General Henry Gordon Bennett, CB, CMG, DSO an Australian War Memorial article

- ^ a b Stanley, Peter. ""Great in adversity": Indian prisoners of war in New Guinea". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

External links

- National Heritage Board, Battlefield Singapore

- Bicycle Blitzkrieg – The Japanese Conquest of Malaya and Singapore 1941–1942

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and the Second World War – the Far East

- The diary of one British POW, Frederick George Pye of the Royal Engineers. Fred Pye was a POW for 3½ years, including time spent building the Burma Railway. He managed to save, write on and bury scraps of paper, and after the war compiled them into a readable form.

- Animated History of the Fall of Malaya and Singapore

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- British rule in Singapore

- Conflicts in 1942

- World War II operations and battles of the Southeast Asia Theatre

- Battles of World War II involving Australia

- Battles and operations of World War II involving India

- Battles of World War II involving Japan

- Battles of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Military of Singapore under British rule

- Military history of Singapore

- Military history of Singapore during World War II

- Military history of India during World War II

- Indian National Army

- 1942 in Japan

- 1942 in Singapore